Isham G. Harris facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Isham G. Harris

|

|

|---|---|

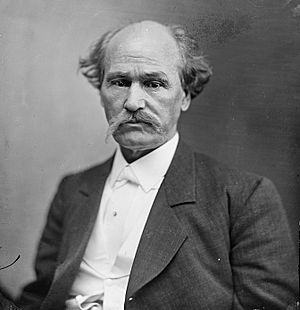

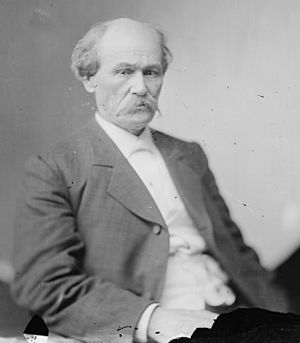

Photograph of Harris by Mathew Brady

|

|

| President pro tempore of the United States Senate | |

| In office January 10, 1895 – March 3, 1895 |

|

| Preceded by | Matt W. Ransom |

| Succeeded by | William P. Frye |

| In office March 22, 1893 – January 7, 1895 |

|

| Preceded by | Charles F. Manderson |

| Succeeded by | Matt W. Ransom |

| United States Senator from Tennessee |

|

| In office March 4, 1877 – July 8, 1897 |

|

| Preceded by | Henry Cooper |

| Succeeded by | Thomas B. Turley |

| 16th Governor of Tennessee | |

| In office November 3, 1857 – March 12, 1862 |

|

| Preceded by | Andrew Johnson |

| Succeeded by | Andrew Johnson as Military Governor |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Tennessee's 9th district |

|

| In office March 4, 1849 – March 3, 1853 |

|

| Preceded by | Lucien B. Chase |

| Succeeded by | Emerson Etheridge |

| Member of the Tennessee Senate | |

| In office 1847–1849 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 10, 1818 Franklin County, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | July 8, 1897 (aged 79) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Elmwood Cemetery, Memphis, Tennessee, U.S. 35°07′19.0″N 90°01′38.7″W / 35.121944°N 90.027417°W |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Martha Mariah Travis |

| Profession | Merchant, Attorney |

| Signature | |

Isham Green Harris (February 10, 1818 – July 8, 1897) was an important American politician. He served as the 16th governor of Tennessee from 1857 to 1862. Later, he became a U.S. senator from 1877 until his death. He was the first governor of Tennessee to come from the western part of the state.

Many people at the time believed Harris was the main reason Tennessee left the Union. He helped the state join the Confederacy during the American Civil War. Harris became well-known in the late 1840s. He spoke out against efforts by northern politicians to end slavery.

He was elected governor as tensions grew between the North and South. After Abraham Lincoln became president in 1860, Harris worked hard to separate Tennessee from the Union. During the war, he helped gather over 100,000 soldiers for the Confederate side. When the Union Army took control of parts of Tennessee in 1862, Harris spent the rest of the war working with various Confederate generals. After the war, he lived outside the U.S. for several years in Mexico and England.

When he returned to Tennessee, Harris became a leader of the state's Bourbon Democrats. As a U.S. Senator, he supported states' rights and policies to increase the amount of money in circulation. In the 1890s, as the Senate's president pro tempore, he led efforts against President Grover Cleveland's plan to cancel the Sherman Silver Purchase Act.

Contents

Early Life and Career Path

Harris was born in Franklin County, Tennessee, near Tullahoma. He was the ninth child of Isham Green Harris, a farmer and minister, and Lucy Davidson Harris. His parents had moved to Tennessee from North Carolina in 1806. He went to Carrick Academy in Winchester, Tennessee, until he was fourteen.

Later, he moved to Paris, Tennessee, to work as a store clerk with his brother, William R. Harris, who was an attorney. In 1838, his brother helped him start his own business in Ripley, Mississippi. This area had just been opened for new settlers after a treaty with the Chickasaw Indians.

While in Ripley, Harris also studied law. Three years later, he sold his successful business for $7,000. He then went back to Paris to continue studying law with Judge Andrew McCampbell. On May 3, 1841, he became a lawyer in Henry County. He started a successful law practice in Paris and was known as one of the best criminal lawyers in the state.

On July 6, 1843, Harris married Martha Mariah Travis, who was nicknamed "Crockett." She was the daughter of Major Edward Travis, a veteran of the War of 1812. Isham and Martha had seven sons. By 1850, their family owned a 300-acre farm and a home in Paris. By 1860, their total property was worth $45,000. This included a plantation in Shelby County.

Entering Politics: State Senate and U.S. House

In 1847, Democrats in Henry County asked Harris to run for a seat in the Tennessee Senate. They hoped he could win against a strong campaign by local Whig politician William Hubbard. Comments made by the Whig congressional candidate, William T. Haskell, hurt Hubbard's campaign, and he left the race. Harris easily won against the Whig replacement, Joseph Roerlhoe.

Soon after joining the Senate, Harris supported a resolution. This resolution spoke against the Wilmot Proviso, which aimed to stop slavery in lands gained during the Mexican–American War. In 1848, Harris was an elector for presidential candidate Lewis Cass, who did not win. He even had a six-hour debate in Clarksville with Aaron Goodrich, who supported Zachary Taylor.

Harris was chosen as the Democratic candidate for Tennessee's 9th District seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1849. He linked his opponent to unpopular ideas of the national Whig Party and won the election easily. During his time in the House, he often spoke against the Compromise of 1850. He also led the House Committee on Invalid Pensions. Harris was re-elected for a second term. However, after Whigs took control of the state legislature in 1851, his district was redrawn. Because of this, he did not run for a third term.

Serving as Governor of Tennessee

In 1856, Harris was chosen as a presidential elector for the state. This meant he traveled across Tennessee to support Democratic candidate James Buchanan. He was much more impressive than the Whig elector, former Governor Neill S. Brown. This campaign made Harris well-known throughout the state.

In 1857, Tennessee's Democratic governor, Andrew Johnson, was badly hurt in a train accident. He could not run for re-election. Harris was nominated to take his place. He campaigned by holding debates with his opponent, Robert H. Hatton. Because of the growing tensions in Congress, these debates were often very heated. Fights sometimes broke out among the people watching, and once even between Harris and Hatton. Hatton could not distance himself from northern abolitionists (people who wanted to end slavery). Harris won the election with 71,178 votes to Hatton's 59,807.

Harris's win was important for Tennessee politics. It marked the end for the state's Know Nothings, a political group that had briefly gained power. It also showed a shift in Tennessee politics toward the Democratic Party. Before this, Whigs and Democrats had been equally strong in the state. Whigs were strong in East Tennessee, Democrats in Middle Tennessee, and both parties were split in West Tennessee. The national debates over the Kansas–Nebraska Act and the Dred Scott case made slavery a central issue in the mid-1850s. This shifted the balance in West Tennessee towards the Democrats. Harris's victory by 11,000 votes was quite large. His predecessor, Johnson, had won by only about 2,000 votes in both 1853 and 1855.

In 1859, Harris ran for re-election. His opponent was John Netherland, who was nominated by a mix of former Whigs, former Know Nothings, and unhappy Democrats. This group was called the Opposition Party. Harris again campaigned by raising fears of northern control. Netherland argued that the U.S. Constitution best protected Southern rights, so Tennessee should stay in the Union. On election day, Harris won by over 8,000 votes. However, the Opposition Party showed its strength by winning 7 of the state's 10 congressional seats.

Secession and the Civil War

Harris supported John C. Breckinridge for president in 1860. He warned that Tennessee might need to leave the Union if "reckless fanatics of the north" gained control of the federal government. After Lincoln was elected in November, Harris called a special meeting of the legislature on January 7, 1861. This meeting ordered a statewide vote on whether Tennessee should consider leaving the Union. Newspapers that supported the Union called Harris's actions treasonous. The Carroll Patriot newspaper in Huntingdon wrote that Harris deserved to be punished more than Benedict Arnold. William "Parson" Brownlow, editor of the Knoxville Whig, strongly disliked Harris. He called him "Eye Sham" and "King Harris," and said his actions were like a dictator's. When the vote was held in February, Tennesseans voted against leaving the Union, with 68,000 votes against and 59,000 for.

After the Battle of Fort Sumter in April 1861, President Lincoln asked Harris to provide 50,000 soldiers to stop the rebellion. Harris read his answer to Lincoln to a large, excited crowd in Nashville on April 17. He said, "Not a single man will be furnished from Tennessee," and that he would rather cut off his right arm than sign the order. On April 25, Harris spoke to a special session of the state legislature. He said the Union had been destroyed by the "bloody and tyrannical policies of the Presidential usurper." He called for Tennessee to end its ties to the United States. Soon after, the legislature allowed Harris to make an agreement with the new Confederate States of America.

In May 1861, Harris began organizing and raising soldiers for what would become the Army of Tennessee. That same month, a steamboat, the Hillman, carrying lead to Nashville from St. Louis, was seized by the Governor of Illinois. In response, Harris seized $75,000 from the customs office in Nashville. On June 8, 1861, Tennesseans voted in favor of leaving the Union, with 104,913 votes for and 47,238 against. A group of pro-Union leaders in East Tennessee, who had voted against leaving, asked Harris to let their region separate from the state and stay with the Union. Harris refused this request. He sent troops under Felix K. Zollicoffer into East Tennessee. In the governor's election later that year, William H. Polk, brother of former President James K. Polk, ran against Harris on a pro-Union platform but lost, 75,300 to 43,495.

The Union Army invaded Tennessee in November 1861 and took control of Nashville by February of the next year. Harris and the state legislature moved to Memphis. But after Memphis also fell, Harris joined the staff of General Albert Sidney Johnston. At the Battle of Shiloh on April 6, Harris saw Johnston slumping in his saddle. He asked if Johnston was wounded, and Johnston replied, "Yes, and I fear seriously." Harris and other staff officers moved the general to a small ditch and tried to help him. However, Johnston died within a few minutes. Harris and the others secretly moved his body to Shiloh Church. They did this so that the Confederate troops would not lose their morale.

Harris spent the rest of the war as an aide-de-camp (a personal assistant) to various Confederate generals. These included Joseph E. Johnston, Braxton Bragg, John B. Hood, and P. G. T. Beauregard. Andrew Johnson was appointed military governor by President Lincoln in March 1862. However, Harris was still recognized as governor by the Confederacy. In 1863, Tennessee's Confederates elected Robert L. Caruthers as a successor to Harris, but Caruthers never took office. Harris was still issuing orders as governor as late as November 1864.

After the war, the United States Congress passed a resolution. This resolution allowed the governor of Tennessee to offer a reward for Harris's capture. Governor Brownlow, who had taken office, issued an arrest warrant for Harris and offered a $5,000 reward. Brownlow described Harris in the warrant, saying, "His eyes are deep and penetrating—a perfect index to a heart of a traitor—with the scowl and frown of a demon resting upon his brow."

Harris fled to Mexico. There, he and several other former Confederates tried to join with Emperor Maximilian. However, after Maximilian's rule ended in 1867, Harris had to flee again, this time to England. Later that year, after learning Brownlow would cancel the warrant, Harris returned to Tennessee. He visited Brownlow in Nashville, who reportedly greeted him kindly. Afterward, Harris returned to Memphis to practice law.

United States Senate Career

By 1877, the Tennessee state legislature was again controlled by Democrats. They elected Harris to one of the state's U.S. Senate seats. One of his first roles, in the 46th Congress (1879–81), was on the District of Columbia Committee. Later, he served on the Committee on Epidemic Diseases from the 49th Congress through the 52nd Congress (1885–93). He also served on the Committee on Private Land Claims in the 54th Congress (1895–97).

During his first term in the Senate, Harris became a leader of Tennessee's Bourbon Democrats. This group of Democrats generally supported laissez-faire capitalism (meaning less government involvement in the economy) and the gold standard (a monetary system where currency is backed by gold). Harris spent his early Senate career supporting strict constructionism (interpreting the Constitution strictly), limited government, states' rights, and low tariffs (taxes on imported goods). In 1884, President-elect Grover Cleveland interviewed him for a position in his cabinet. In 1887, Harris gave a strong speech supporting the repeal of the Tenure of Office Act. In 1890, Harris spoke out against the Lodge Bill. This bill would have protected voting rights for African Americans in the South. Harris argued it violated states' rights.

Even though he was a Bourbon Democrat, Harris also supported "Silver Democrat" policies. He represented an agricultural state and believed that policies supporting silver would help farmers. He supported the Bland–Allison Act of 1878. This act allowed the federal government to buy silver to prevent crop prices from falling too much. He also supported the act's replacement, the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890. In 1893, President Cleveland was worried that the Sherman Act was reducing the U.S. gold supply. He sought to repeal it. When the vote came up in the Senate in October, Harris, as president pro tempore, tried to stop the act's repeal by using a filibuster (a long speech to delay a vote). However, he was not successful. Unhappy about the repeal of the Sherman Act, Harris campaigned for William Jennings Bryan in 1896, who was against the gold standard and did not win the presidency.

Later Life and Legacy

Harris died while still in office on July 8, 1897. His funeral was held in the Senate chamber of the United States Capitol. Congressman Walter P. Brownlow, a nephew of Harris's old rival Parson Brownlow, was among those who gave a speech honoring him. Harris is buried at Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis, Tennessee.

See also

- List of governors of Tennessee

- List of United States Congress members who died in office (1790–1899)