William G. Brownlow facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Gannaway Brownlow

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 17th Governor of Tennessee | |

| In office April 5, 1865 – February 25, 1869 |

|

| Preceded by | Andrew Johnson as Military Governor |

| Succeeded by | Dewitt Clinton Senter |

| United States Senator from Tennessee |

|

| In office March 4, 1869 – March 3, 1875 |

|

| Preceded by | David T. Patterson |

| Succeeded by | Andrew Johnson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 29, 1805 Wythe County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | April 29, 1877 (aged 71) Knoxville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Resting place | Old Gray Cemetery Knoxville, Tennessee |

| Political party | Whig American Republican |

| Spouse | Eliza O'Brien (m. 1836) |

| Relations | Walter P. Brownlow (nephew) |

| Children | Susan, John Bell, James, Mary, Fannie, Annie, Caledonia Temple |

| Profession | Minister, newspaper editor |

| Signature | |

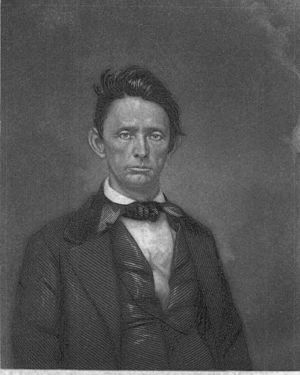

William Gannaway "Parson" Brownlow (August 29, 1805 – April 29, 1877) was an important American figure. He was a newspaper publisher, a Methodist minister, and a politician. He served as the 17th Governor of Tennessee from 1865 to 1869. Later, he became a United States Senator for Tennessee from 1869 to 1875.

Brownlow became well-known in the late 1830s. He was the editor of the Whig newspaper in East Tennessee. This newspaper supported the ideas of the Whig Party. It also strongly opposed states leaving the Union before the American Civil War. Brownlow's strong and sometimes extreme views made him a very debated person in Tennessee politics. He was also a controversial figure during the Reconstruction Era.

He started his career as a Methodist circuit rider in the 1820s. He was known for his strong debates with other religious leaders. As a newspaper editor, he often attacked his opponents. Despite this, he gained many loyal readers.

Brownlow returned to Tennessee in 1863. In 1865, he became governor with the support of the U.S. Army. He joined the Radical Republicans. He often disagreed with his political rival, Andrew Johnson. Brownlow's policies helped Tennessee become the first former Confederate state to rejoin the Union in 1866. This meant Tennessee avoided a long period of federal military rule.

Brownlow used the Tennessee government to give African-American men the right to vote. They could also run for public office after the Civil War. However, former Confederate leaders and military officers, often through groups like the Ku Klux Klan, tried to take away these rights.

Contents

Early Life and Religious Path

Brownlow was born in Wythe County, Virginia, in 1805. He was the oldest son of Joseph A. Brownlow and Catherine Gannaway. His father, a traveling farmer, died in 1816 in Blountville, Tennessee. His mother died three months later. William became an orphan at age 10. He and his four siblings were separated and lived with relatives. William spent his childhood on his uncle John Gannaway's farm. At 18, he went to Abingdon. There, he learned carpentry from another uncle, George Winniford.

In 1825, Brownlow had a strong spiritual experience at a church gathering. He felt a sudden sense of peace and happiness. He decided to stop carpentry and study to become a Methodist minister. In 1826, he joined the traveling ministry, known as "circuit riders."

In the Southern Appalachian region, different Christian groups like Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians competed for followers. Brownlow was very strong in defending his Methodist Church. He often criticized the beliefs of other groups.

His first assignment as a circuit rider was in the Black Mountain area of North Carolina in 1826. Here, he first met Baptists and developed a strong dislike for them. He thought their practices, like foot washing, were strange.

In 1827, Brownlow was assigned to the Maryville, Tennessee area. There was a strong Presbyterian presence there. He remembered being constantly bothered by a young Presbyterian minister who criticized Methodism.

In 1832, Brownlow was sent to the Pickens District in South Carolina. He said this area was "overrun with Baptists." He wrote a 70-page pamphlet criticizing the Baptists there. He had to quickly leave the district as angry residents wanted to harm him. This experience influenced his later strong views against states leaving the Union.

Brownlow later had his book Helps To The Study of Presbyterianism published in 1834. It discussed the separation of church and state and the Presbyterian Church's influence.

Marriage and New Path

Brownlow married Eliza Ann O'Brien in 1836 in Carter County, Tennessee. They lived in her hometown of Elizabethton. Brownlow started working as a clerk at her family's iron foundry, O'Brien Furnace. He often traveled by flatboat on the Watauga River and Holston River. He brought iron shipments from the furnace to Knoxville.

Even though Brownlow stopped being a circuit rider in 1836, he continued to defend Methodism. He did this in his newspaper articles, books, and speeches. For the rest of his life, he was known as the "Fighting Parson."

Starting a Newspaper Career

Brownlow began his newspaper work in 1838. He wrote for the Elizabethton Republican and Manufacturer's Advocate. This weekly newspaper supported Whig politics. When Brownlow became its editor, it had about 300 subscribers.

Historian Stephen Ash noted Brownlow's sharp writing style. He said Brownlow was known for his "vitriolic tongue and pen." Brownlow supported many causes, including Methodism, the Whig Party, and the Union. He also supported temperance (avoiding alcohol) and anti-immigrant views. He often criticized his opponents fiercely. This included Baptists, Presbyterians, Catholics, Democrats, and others. He made many enemies, and some even tried to harm him.

A lawyer named T.A.R. Nelson suggested Brownlow start a newspaper. This paper would support Whig Party candidates. Brownlow partnered with Mason R. Lyon. They launched their weekly Tennessee Whig on May 16, 1839. A few weeks later, they renamed it the Elizabethton Whig.

Brownlow's strong writing style caused problems in Elizabethton. He began arguing with Landon Carter Haynes, a local Whig who became a Democrat. Haynes later moved to Jonesborough and edited a newspaper there.

Brownlow and his newspaper also moved to Jonesborough in the same year. The newspaper was renamed the Jonesboro Whig. Brownlow had a new business partner, Valentine Garland. Their partnership was short-lived. Brownlow later confronted Haynes in Jonesborough. Haynes shot Brownlow in the thigh. Haynes then became editor of the rival Democratic Tennessee Sentinel. Brownlow and Haynes continued to criticize each other in their newspapers for years.

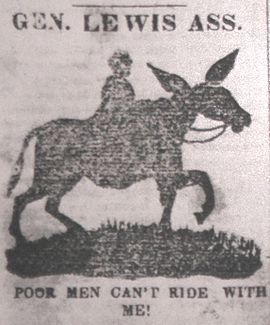

In 1845, Brownlow ran against Andrew Johnson for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. He used the Whig to support his campaign. Johnson won the election.

Brownlow supported Whig policies. These included a national bank and federal money for public improvements. He wanted to improve steamboat travel on the Tennessee River near Chattanooga. He also wanted to develop industries in northeast Tennessee. He believed in a weaker presidency. He called Andrew Jackson a "curse" to the nation. He attacked Jackson's supporters in his 1844 book, A Political Register. Brownlow's political hero was Kentucky senator Henry Clay. His son remembered his father crying when Clay lost the 1844 presidential election.

In May 1849, Brownlow moved the Whig to Knoxville, Tennessee. He was already known there for his arguments with the Democratic Standard newspaper. Before leaving Jonesboro, Brownlow was attacked. He blamed Knoxville's newspaper owners, who feared his competition. In Knoxville, he started a long editorial fight with Knoxville Register editor John Miller McKee.

Brownlow joined the Sons of Temperance in 1850. He promoted temperance in the Whig. After the Whig Party ended in the mid-1850s, he joined the Know Nothing movement. He shared their anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant views. In 1856, he published a book called Americanism Contrasted with Foreignism, Romanism and Bogus Democracy. This book criticized Catholicism, foreigners, and Democratic politicians.

In the late 1850s, Brownlow focused on Knoxville's Democratic Party leaders. He argued with the Southern Citizen, a pro-secession newspaper. He even threatened its publisher, William G. Swan, with a revolver. After a bank failed in 1858, Brownlow attacked its directors. His criticisms forced some to leave the state. He sued another director, J. G. M. Ramsey, and won money for the bank's customers.

Because of his strong opposition to states leaving the Union, Brownlow was jailed by Confederate authorities in December 1861. He was later pardoned and forced to leave for the northern United States.

Religious Debates

Even after leaving the preaching circuit, Brownlow continued to defend the Methodist faith. In 1843, his argument with Haynes led to Haynes being removed from the Methodist clergy. That same year, J.M. Smith, a newspaper editor, accused Brownlow of stealing jewelry. Brownlow denied it. Smith tried to have Brownlow removed from the church, but failed.

In the late 1840s, Brownlow argued with Presbyterian minister Frederick Augustus Ross. Ross had criticized Methodism in his Calvinist Magazine. Ross said the Methodist Church was like a "great iron wheel" that would crush American freedom. He also claimed that the founder of the Methodist Church, John Wesley, believed in ghosts.

Brownlow responded with a column in the Jonesborough Whig called "F.A. Ross' Corner." In 1847, he started a separate paper, the Jonesborough Quarterly Review, to argue against Ross. Brownlow said that while believing in ghosts was common in Wesley's time, many Presbyterian ministers still believed in such things. He criticized Ross and his family. This argument continued until Brownlow moved to Knoxville in 1849.

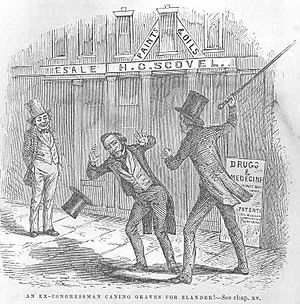

In 1856, James Robinson Graves, a Baptist minister, wrote a book called The Great Iron Wheel. It criticized Methodists using similar ideas to Ross. Brownlow quickly wrote his own book, The Great Iron Wheel Examined; Or, Its False Spokes Extracted, that same year. He accused Graves of spreading false information. He also claimed that Baptist ministers were mostly uneducated. Brownlow also made fun of the Baptist way of baptism, immersion.

Slavery and the Civil War

Brownlow's views on slavery changed over time. While he owned slaves and wrote in favor of slavery before the Civil War, his name also appeared on an anti-slavery petition in 1834. In the early 1840s, he supported the American Colonization Society. This group wanted to send freed slaves to Liberia. Later, he became a strong supporter of slavery. Historians suggest this change might have been due to social pressure or rivalry between Northern and Southern Methodists.

By the 1850s, Brownlow strongly believed slavery was "ordained by God." He gave speeches defending slavery using religious arguments. In 1858, he challenged Northern abolitionists to debate him. He refused to debate Frederick Douglass because of his race. He then debated Abram Pryne, an abolitionist clergyman, in Philadelphia in September 1858. Brownlow argued that slavery should continue and that it had always existed.

During the Civil War, Brownlow changed his mind again. He began to call for the end of slavery.

Brownlow was strongly against Southern states leaving the Union. He believed that those who wanted to secede aimed to create a country ruled by wealthy aristocrats. In 1860, he supported his friend, pro-Union candidate John Bell, for president. In September 1860, he interrupted a rally in Knoxville to argue with a pro-Breckinridge speaker. When South Carolina left the Union in November 1860, Brownlow criticized the state.

By 1861, the Knoxville Whig had 14,000 subscribers. People who wanted to secede saw it as the reason for strong pro-Union feelings in East Tennessee. Knoxville Democrats tried to fight Brownlow by making J. Austin Sperry editor of the Knoxville Register. This started a newspaper war. Brownlow called Sperry names and mocked his newspaper's small circulation.

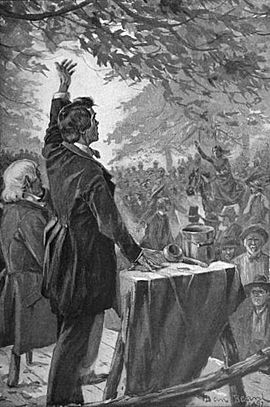

In the spring of 1861, Brownlow and his friends gave many pro-Union speeches across East Tennessee. In May and June 1861, Brownlow represented Knox County at the East Tennessee Convention. They tried to get permission for East Tennessee to form a separate, Union-aligned state, but they failed. After Tennessee left the Union in June 1861, Brownlow used the Whig to defend Union supporters. By the fall of 1861, the Whig was the only pro-Union newspaper left in the South. He famously said, "We intend to fight the secessionists until hell freezes over, and then fight them on ice."

During the American Civil War

On October 24, 1861, Brownlow stopped publishing the Whig. He announced that Confederate authorities were planning to arrest him. On November 4, he went into hiding in the Great Smoky Mountains. He stayed with friends in Wears Valley and Tuckaleechee Cove. On November 8, pro-Union fighters burned several railroad bridges in East Tennessee. Confederate leaders suspected Brownlow was involved, but he denied it.

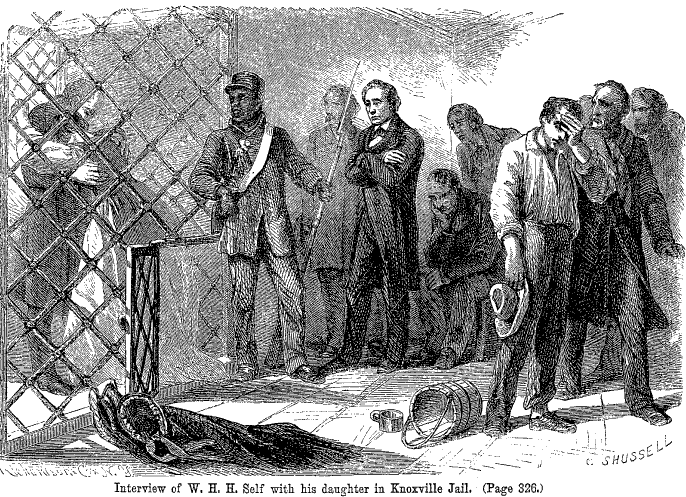

Brownlow asked for permission to leave the state. The Confederate Secretary of War, Judah P. Benjamin, granted it. However, on December 6, as he was preparing to leave Knoxville, he was arrested and jailed on charges of treason. While in jail, Brownlow saw the trials of many accused bridge-burners. He wrote about this in his diary. He protested his imprisonment to Benjamin. After Benjamin threatened to pardon Brownlow, he was released in late December 1861.

Brownlow was taken to Nashville, which the Union Army had captured. He crossed into Union territory on March 3, 1862. His fight against secession made him famous in the northern states. He began a speaking tour in April. He spoke in Cincinnati, Dayton, Indianapolis, Chicago, and Columbus, Ohio. He also spoke in Pittsburgh and at Independence Hall in Philadelphia.

In Philadelphia, a publisher convinced Brownlow to write a book. It was called Sketches of the Rise, Progress, and Decline of Secession. He finished it in May 1862. By September, the book had sold over 100,000 copies. Brownlow then traveled to the northeast, speaking in New York City and Boston. He also toured western New York and Illinois. In June, he testified at the trial of West Hughes Humphreys, a Confederate judge.

In June 1862, workers gave a revolver to Brownlow's daughter, Susan. She had threatened to shoot two Confederate soldiers who tried to remove the American flag from their Knoxville home. Later that year, a book called Parson Brownlow and the Unionists of East Tennessee was published. In 1863, a musical piece called Parson Brownlow's Quick Step was released.

Brownlow returned to Nashville in early 1863. He followed Ambrose Burnside's forces back to Knoxville in September. In November 1863, he relaunched the Whig newspaper. He called it Knoxville Whig and Rebel Ventilator. He began to seek revenge against former Confederates. In 1864, he worked to reconnect his church's Holston Conference with the northern Methodists.

Governor of Tennessee During Reconstruction

Brownlow was chosen as the candidate for governor by a group of Tennessee Unionists in January 1865. He was the only one nominated. This group also proposed state constitutional changes to outlaw slavery and cancel the act of secession. This made Tennessee the first Southern state to leave the Confederacy. The military governor, Andrew Johnson, had put in place rules that stopped former Confederates from voting. On March 4, Brownlow was elected with a large majority. The changes to the constitution also passed easily.

In early April 1865, Brownlow arrived in Nashville. He was sworn in on April 5. The next day, he submitted the 13th Amendment for approval. After this amendment was approved, Brownlow proposed laws to punish former Confederates. He took away the voting rights of anyone who had supported the Confederacy for at least five years. For Confederate leaders, it was fifteen years. He later made this law stronger. It required voters to prove they had supported the Union. He also tried to fine people for wearing a Confederate uniform. He tried to stop Confederate ministers from performing marriages.

After a few months, Brownlow felt that President Johnson was too soft on former Confederate leaders. He joined the Radical Republicans, who strongly opposed Johnson. In the August 1865 elections for Congress, Brownlow rejected many votes. This allowed a Radical candidate to win in one district. A small group of state lawmakers turned against Brownlow. They said his actions were too harsh and sided with Johnson. By 1866, Brownlow believed some Southerners were planning another rebellion. He thought Andrew Johnson would lead it.

Fighting the Ku Klux Klan

Brownlow began to call for civil rights for freed slaves. He stated that "a loyal Negro was more deserving than a disloyal white man." In May 1866, he submitted the 14th Amendment for approval. Radical Republicans in Congress supported this, but Johnson opposed it. A small group of pro-Johnson lawmakers tried to leave Nashville to stop the vote. They were arrested and brought back. This allowed the amendment to pass. Brownlow sent a message to Congress, criticizing Johnson. Tennessee was then readmitted to the Union.

The Radicals nominated Brownlow for a second term as governor in February 1867. His opponent was Emerson Etheridge. That same month, the legislature passed a law giving black residents the right to vote. Groups called Union Leagues were formed to help freed slaves vote. Members of these groups often clashed with former Confederates, including members of the growing Ku Klux Klan. Brownlow organized a state guard, led by General Joseph Alexander Cooper, to protect voters. With former Confederates unable to vote, Brownlow easily defeated Etheridge.

By 1868, violence from the Klan had increased a lot. The Klan sent Brownlow a death threat. General Nathan B. Forrest joined the Klan. He became its first Grand Wizard. This was partly in response to Brownlow's policies that took away voting rights from former Confederates. The William G. Brownlow Family Papers contains a letter from a Klan leader threatening Governor Brownlow's life.

Forrest said in an interview that he did not recognize Brownlow's government as legal. He warned that if Brownlow's militia caused trouble, they and Brownlow's government would be destroyed. Forrest claimed the Klan had many members in Tennessee and other Southern states. He said the Klan supported the Democratic Party. Forrest denied being a member of the Klan himself.

Forrest and twelve other Klan members asked Brownlow to stop their activities if Confederates were given the right to vote. Brownlow refused. He reorganized the state guard and asked the legislature for more power to enforce laws.

Brownlow supported Ulysses S. Grant for president in 1868. He asked for federal troops to be sent to 21 Tennessee counties to stop Klan activity. The state legislature gave him the power to throw out entire counties' voter registrations if he thought they included people who shouldn't vote. In October 1868, before the election, Brownlow removed all registered voters in Lincoln County. After the election, two Radical candidates lost. Brownlow believed Klan threats caused their defeat. He rejected votes from certain counties, allowing his candidates to win.

In February 1869, as his term was ending, Brownlow put nine counties under martial law. He said this was needed to stop Klan violence. He also sent state guard companies to occupy Pulaski, where the Klan was founded. After Brownlow left office in March, Forrest ordered the Klan to stop all activities.

U.S. Senate and Later Life

After being reelected governor in 1867, Brownlow decided not to seek a third term. Instead, he sought election to the U.S. Senate. In October 1867, the state legislature elected Brownlow to the Senate. By the time he was sworn in on March 4, 1869, he was very weak due to a nervous disease. The Senate clerk had to read his speeches for him. One of his speeches defended Ambrose Burnside, the Union general who had freed Knoxville in 1863.

Brownlow was a member of the U.S. Senate when important laws were passed. These included the Enforcement Act of 1870 and the Second Enforcement Act of 1871. These laws gave the President power to fight the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacy groups.

After his Senate term ended in 1875, Brownlow returned to Knoxville. His successor as governor, DeWitt Clinton Senter, had reversed most of Brownlow's policies. This allowed Democrats to regain control of the state government. Brownlow had sold the Whig in 1869. He then bought a share in the Knoxville Chronicle, a Republican newspaper. The paper's name was changed to the Knoxville Whig and Chronicle. In 1876, Brownlow supported Rutherford B. Hayes for president. In December of that year, he spoke at the opening of Knoxville College. This college was established for African-American residents.

On April 28, 1877, Brownlow collapsed at his home. He died the next afternoon. He was buried in Knoxville's Old Gray Cemetery. His funeral procession was described as the largest in the city's history at that time.

Legacy and Family

In 1870, William Rule, who had worked for the Whig, started the Knoxville Chronicle. He saw it as the Whig's Republican successor. Rule continued editing this paper, which became The Knoxville Journal, until his death in 1928. The Knoxville Journal was one of Knoxville's daily newspapers until it closed in 1991. Adolph Ochs, who later published New York Times, began his career at the Chronicle in the early 1870s.

William Rule wrote that Brownlow was a "master of invective and burning sarcasm." He said Brownlow was good at criticizing others. J. Austin Sperry, Brownlow's rival editor, admitted that Brownlow was a remarkable judge of people.

Brownlow's colleague, Oliver Perry Temple, wrote that Brownlow was easy to persuade if it was something he believed was right. But it was impossible to force him to do something he didn't agree with.

Brownlow remained a debated figure for many years after his death. In 1999, historian Stephen Ash wrote that just saying his name in Tennessee could cause strong reactions. Brownlow has been called "Tennessee's worst governor" and the "most hated man in Tennessee History." A 1981 poll of Tennessee historians ranked him last among the state's governors.

Journalist Steve Humphrey argued that Brownlow was a talented newspaper editor. He showed this in his reports on events like the opening of the Gayoso Hotel and Knoxville's 1854 cholera outbreak.

The official portrait of Governor William G. Brownlow was briefly displayed in the Tennessee state capitol building in 1987. It was later removed.

Family Life

Brownlow married Eliza O'Brien (1819–1914) in 1836. They had seven children: Susan, John Bell, James Patton, Mary, Fannie, Annie, and Caledonia Temple.

Eliza O'Brien Brownlow lived in the family home in Knoxville until her death in 1914 at age 94. Many visitors, including three presidents (William McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt, and William Howard Taft), visited Eliza Brownlow when they were in Knoxville.

The Brownlows' older son, John Bell Brownlow (1839–1922), was a colonel in the Union Army during the Civil War. After his father's death, he helped develop a Knoxville neighborhood. It was known as "Brownlow" for years. Brownlow Elementary School, which served this area, still stands and has been turned into apartments.

The Brownlows' younger son, James Patton Brownlow (1842–1879), was also a colonel in the Union Army. He was later promoted to brigadier general by President Andrew Johnson. He served as an adjutant general in the state guard when his father was governor.

Walter P. Brownlow (1851–1910), a nephew of Parson Brownlow, served as a U.S. congressman from Tennessee's 1st district.

James Stewart Martin (1826–1907), another nephew of Parson Brownlow, served as a U.S. congressman from Illinois.

Louis Brownlow (1879–1963), a famous political scientist and city planner, was a grandson of one of Parson Brownlow's first cousins. He served as Knoxville's city manager in the 1920s.

Works by William G. Brownlow

Newspapers

- The Whig, Brownlow's main newspaper, was published under different names:

- Tennessee Whig (1839 in Elizabethton)

- Elizabethton Whig (1839 in Elizabethton)

- The Whig (1840–1841 in Jonesborough)

- Jonesborough Whig (1841–1842)

- Jonesborough Whig and Independent Journal (1842–1849)

- Brownlow's Knoxville Whig and Independent Journal (1849–1855 in Knoxville)

- Brownlow's Knoxville Whig (1855–1861)

- Brownlow's Weekly Whig (1861)

- Brownlow's Knoxville Whig, and Rebel Ventilator (1863–1866)

- Brownlow's Knoxville Whig (1866–1869)

- Knoxville Weekly Whig (1869–1870)

- Weekly Whig and Register (c. 1870–1871)

- The Knoxville Whig and Chronicle (1875–1877), co-owned with William Rule

Books

- Helps to the Study of Presbyterianism (1834)

- A Narrative of the Life, Travels, and Circumstances Incident Thereto, of William G. Brownlow (1834, a supplement to Helps to the Study of Presbyterianism)

- Baptism Examined: Or, the True State of the Case (1842)

- A Political Register, Setting Forth the Principles of the Whig and Locofoco Parties in the United States, With the Life and Public Services of Henry Clay (1844)

- Americanism Contrasted with Foreignism, Romanism and Bogus Democracy (1856)

- The Great Iron Wheel Examined; Or, Its False Spokes Extracted, and an Exhibition of Elder Graves, Its Builder (1856)

- Sketches of the Rise, Progress, and Decline of Secession; With a Narrative of Personal Adventures Among the Rebels (1862)

Speeches and Debates

- "Speech, Being a Reply to Thomas Dog Arnold" (Knoxville, Tennessee, 1852)

- "A Sermon on Slavery: A Vindication of the Methodist Church, South: Her Position Stated" (Knoxville, Tennessee, 1857)

- "Ought American Slavery to be Perpetuated? A Debate Between Rev. W.G. Brownlow and Rev. A. Pryne Held At Philadelphia, September, 1858]" (1858)

- "Speech of Parson Brownlow, of Tennessee, Against the Great Rebellion" (New York, 1862)

- "Address to the Loyal People of Tennessee" (Knoxville, Tennessee, 1868)

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |