East Tennessee Convention facts for kids

The East Tennessee Convention was a series of important meetings held by people in East Tennessee who wanted to stay loyal to the United States during the American Civil War. They met three times. The most famous thing they did was say that the state government of Tennessee was wrong to leave the United States. They also asked if East Tennessee could become its own state and stay with the Union, similar to how West Virginia did. However, the state government said no. Later in 1861, the Confederate Army took control of the region.

The Convention first met in Knoxville on May 30–31, 1861. This was after Tennessee's government declared its "independence" from the U.S. and joined forces with the Confederacy. Congressman T. A. R. Nelson was chosen to lead the meeting. The group decided that the state government's actions were against the law. The Convention met again in Greeneville from June 17 to June 20, 1861, after Tennessee officially voted to leave the Union. In this second meeting, they formally asked the state government to let East Tennessee separate. The Convention met one last time in Knoxville from April 12 to April 16, 1864. This meeting discussed President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation and his plan for states to rejoin the Union. This final meeting had strong disagreements about slavery.

Even though the Convention didn't succeed in making East Tennessee a separate Union state, it was very important. It helped unite the Union supporters in the region and gave them strong leaders. Many of these leaders later held important jobs in government after the war.

Contents

Why East Tennessee Was Different

Throughout the early 1800s, East Tennessee often disagreed with the other parts of Tennessee: Middle Tennessee and West Tennessee. Many people in East Tennessee felt that the state government favored the other two regions, especially when it came to funding for roads and other improvements. In the 1840s, some leaders, like future President Andrew Johnson, even tried to form a separate state called "Franklin" in East Tennessee. This idea didn't work out, but the thought of East Tennessee being its own state came up again many times over the next 20 years.

Political Parties and Divisions

From the late 1830s to the early 1850s, Tennessee politics were split between the Democratic Party and the Whig Party. The Whigs were very popular in East Tennessee. But the Whig Party started to fall apart in the mid-1850s because of disagreements over slavery. Most Northern Whigs joined the new Republican Party, but Southern Whigs didn't like the Republicans' anti-slavery views.

Some important East Tennessee Whigs became Democrats. Others joined new parties like the American Party (also called the "Know Nothings"). By the late 1850s, former Whigs, Know Nothings, and some unhappy Democrats formed the Opposition Party. Their goal was to fight against the growing idea of states leaving the Union.

Before 1857, elections for governor in Tennessee were very close. But when Isham G. Harris, a strong supporter of slavery, was elected governor in 1857 and again in 1859, he won by much larger margins. Democrats also gained control of the state legislature. This showed that feelings in West Tennessee were shifting more towards the Democrats and supporting slavery.

The 1860 Election and Secession

In the 1860 presidential election, many former Whigs in East Tennessee supported the Constitutional Union Party. This party was against both states leaving the Union and ending slavery. Their candidate, John Bell, was from Tennessee.

After Abraham Lincoln won the election in November 1860, Southern Democrats became convinced that Lincoln would end slavery. They began calling for states to leave the Union. In Knoxville, there were two tense meetings between those who wanted to leave the Union and those who wanted to stay. After this, Unionist leaders held rallies across East Tennessee to oppose leaving the Union.

On February 9, 1861, Tennessee held a statewide vote to decide if they should have a meeting to discuss leaving the Union. Union supporters won this vote, with 69,675 votes against the meeting and 57,789 for it. In East Tennessee, about 81% of voters said no to the meeting. Most counties in East Tennessee voted against it, except for Sullivan and Meigs (by a small margin).

Why East Tennesseans Stayed Loyal

Even though slavery was a big issue across the country, East Tennessee Unionists had different reasons for opposing leaving the Union. There had been a movement against slavery in East Tennessee earlier in the 1800s, but it had mostly disappeared by the 1840s. By 1860, the Unionist leaders in the region were against both leaving the Union and ending slavery. Many members of the East Tennessee Convention actually owned enslaved people.

The main reasons for strong Union support in East Tennessee were:

- Long-standing political disagreements with Middle and West Tennessee.

- Economic differences, including a much smaller enslaved population compared to the rest of the South.

- The region's isolated, mountainous geography.

First Knoxville Meeting

The Unionists' victory in February 1861 didn't last long. After the Battle of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, many people in Tennessee started to support leaving the Union. Governor Harris refused Lincoln's request for troops to fight the rebellion. Instead, he worked to join Tennessee with the Confederacy. In early May, the state legislature passed laws to form a military alliance with the Confederacy and declared Tennessee's "independence" from the U.S. A new vote was set for June 8 for Tennesseans to decide if they would accept this declaration and join the Confederacy.

Unionists in Tennessee strongly criticized the state government's actions, calling them illegal. But they still started a strong campaign for the June 8 vote. In mid-May, several Unionist leaders in Knoxville met at the law office of Oliver Perry Temple. They decided to hold a convention at the end of the month to plan their strategy. One of them, Connally Trigg, wrote a public notice that was printed in the Knoxville Whig newspaper on May 18. In the days that followed, counties across the region held smaller meetings to choose their representatives for the main convention. These county meetings were big events, often with passionate speeches and music.

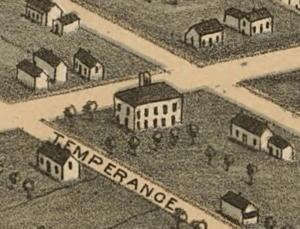

On May 30, the East Tennessee Convention gathered 469 representatives from 28 East Tennessee counties. They met in a grove near Temperance Hall in East Knoxville. The Reverend Thomas William Humes gave the opening speech. Congressman T. A. R. Nelson was chosen as president. James G. Spears was chosen as vice president, and John M. Fleming was named secretary. Other officials were also chosen.

After speaking for an hour, Nelson chose a 26-person committee to create a set of resolutions in response to the state government's actions. While this committee met privately, former Congressman Thomas D. Arnold gave a powerful two-hour speech to the rest of the convention. On the morning of May 31, Senator Andrew Johnson spoke for three hours.

The committee announced its proposed resolutions on May 31, interrupting Johnson's speech. After a short discussion, they were approved. The resolutions praised the right to gather freely, criticized the legislature for breaking state and federal laws, condemned leaders who wanted to leave the Union, and declared the June 8 vote and the state's military alliance with the Confederacy illegal. Nelson, as president, was given the power to call the convention together again in the future and choose where it would meet.

What Happened Next

After the convention ended, its leaders started a speaking tour. They hoped to stop those who wanted to leave the Union from winning the June 8 vote. Nelson and Johnson, who had been campaigning together, continued their efforts. The fiery newspaper publisher William G. Brownlow defended the convention's actions in his newspaper, the Knoxville Whig. On the other hand, the pro-secession newspaper Knoxville Register strongly criticized the convention, calling it selfish and its resolutions treasonous.

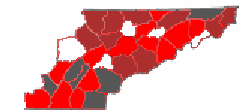

On June 8, those who wanted to leave the Union won. Voters statewide approved leaving the Union by a vote of 108,418 to 46,996. However, while 86% of voters in Middle and West Tennessee approved, nearly 70% of East Tennessee voters still opposed it. Most counties in East Tennessee voted against leaving, except for Sullivan, Meigs, Monroe, Rhea, Sequatchie, and Polk.

The vote results showed that opposition to leaving the Union was strongest in the mountainous northern East Tennessee counties. For example, Scott County voted 99% against leaving, Sevier County 96%, Carter County 94%, Campbell County 94%, and Anderson County 93%. Rhea County showed the biggest change, going from 88% against leaving in February to 64% for leaving in June.

Greeneville Meeting

-

T. A. R. Nelson (president)

-

James G. Spears (vice president)

On June 11, 1861, Nelson used his power from the Knoxville meeting to call the convention to meet again in Greeneville on June 17. Greeneville was chosen instead of Knoxville because there were threats against Union supporters in Knoxville. On the afternoon of June 17, 285 representatives from across the region gathered at the Greene County Courthouse. This was fewer than the 469 who had met in Knoxville three weeks earlier. Only 130 of the Greeneville representatives had been at the Knoxville meeting.

The convention began with a prayer. The same officers from the Knoxville meeting kept their positions. Nelson appointed new members to the business committee for those who weren't there. On the first evening, Nelson presented a "Declaration of Grievances" (a list of complaints) and some resolutions. These were immediately sent to the business committee. The next two days were spent discussing different ideas. Oliver Perry Temple, a representative from Knox County, later wrote that many of these ideas were "wild and visionary."

The Declaration of Grievances suggested that the June 8 election results were unfair due to cheating and threats in Middle and West Tennessee. It also argued against claims that the East Tennessee Convention didn't truly represent the feelings of East Tennessee. The Declaration said that Southerners' rights had not been violated. It accused leaders who wanted to leave the Union of acting unfairly and causing the country to go to war. The Declaration was approved with little disagreement, though the final version was made less harsh by Temple and another Knox County representative, Horace Maynard.

Unlike the Declaration of Grievances, the resolutions proposed by Nelson were debated for a long time. His proposals basically said that the Convention would not accept Tennessee's declaration of independence or support the Confederacy. They stated that East Tennessee counties would remain part of the Union as the State of Tennessee. They also said East Tennessee would stay neutral in any war if left alone. They would fight back if Confederate troops tried to stay in the region or if Unionists were attacked. They would also form local military groups for self-defense.

Many representatives felt Nelson's resolutions were too extreme and would lead to fighting. On the third day (June 20), Oliver Perry Temple offered a different set of resolutions. These said the Convention wanted peace. They stated that the state government's actions to leave the Union were illegal. They would ask the state legislature for permission to form a new state. And a meeting for this proposed new state would be held in Kingston. The president (Nelson) would choose the date, and counties would have representatives based on their population.

A heated debate followed Temple's proposals. Supporters of Nelson's resolutions accused Temple's supporters of being afraid. Temple's supporters argued that Nelson's supporters were being unreasonable. On the morning of the fourth day (June 21), the business committee voted for Temple's resolutions. After more debate, Temple's resolutions were adopted.

Temple, John Netherland, and James P. McDowell were chosen to deliver a formal request to the state legislature. This request asked for East Tennessee to be allowed to form a separate state. Another motion warned that if Confederate troops continued to bother Unionists, Unionists would fight back. This was because a group of Confederate soldiers passing through Greeneville had bothered the Convention representatives, stealing their breakfast and cutting down an American flag.

The Tennessee state legislature received the Convention's request on June 28, 1861. They formed a committee to look at it. This committee questioned if the Convention truly represented East Tennessee. They hoped East Tennesseans would eventually accept the results of the June 8 vote. They said no action would be taken until the next legislative session.

Civil War and Second Knoxville Meeting

Soon after the Convention ended, Brownlow's Whig newspaper declared, "It is now for the Secessionists in the Legislature to say whether we shall separate in peace, or have a disastrous Civil War." The New York Times praised the Convention, saying the "bold mountaineers of Tennessee have dared to be free." Pro-secession newspapers, however, strongly criticized the Convention. The Knoxville Register called it "a few tory leaders" trying to cause bloodshed. The Memphis Appeal called the Convention "Traitors in Council."

On July 10, 1861, T. A. R. Nelson called for the Kingston convention (to organize a new state) to meet on August 31. However, in the following weeks, Confederate troops led by Felix K. Zollicoffer took control of East Tennessee. This meeting never happened. Nelson, who was a member of Congress, tried to escape to Washington, D.C., but was captured. He was released after agreeing to stay neutral during the war. George W. Bridges, another Convention representative elected to Congress, was arrested but later escaped. William G. Brownlow, a famous Unionist, was arrested and jailed before being allowed to flee to the North. Lawyers John Baxter and Oliver Perry Temple stayed in Knoxville and helped Unionists facing charges in Confederate courts.

Many Convention representatives joined the Union Army. At the Greeneville meeting, Robert K. Byrd, Joseph A. Cooper, Richard M. Edwards, S. C. Langley, and William J. Clift secretly agreed to go home and raise troops to defend the region. Others fled to Kentucky to join the Union army. Cooper and James G. Spears both became generals. More than two dozen Convention representatives became colonels, and many others served as officers.

One of the boldest acts involving East Tennessee Convention representatives during the war was the East Tennessee bridge-burning conspiracy. This was a plan to destroy nine railroad bridges to help a Union invasion. William B. Carter, a Convention representative, planned this. He was helped by other representatives. On the night of November 8, 1861, they destroyed five bridges. However, the Union Army did not invade. In response, Zollicoffer declared military rule in East Tennessee.

Many Convention representatives suffered greatly for their Union support, and some died. Tolliver Staples was captured and killed by Confederate guerrillas. John McGaughey was killed by Confederate guerrillas in 1865. Montgomery Thornburgh died in a Confederate prison. William J. Clift almost died from injuries while escaping a Confederate prison. Convention secretary John M. Fleming and Robert H. Hodsden were arrested but later cleared.

Second Knoxville Meeting (1864)

President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, issued in early 1863, caused disagreements among Unionists in Tennessee. Andrew Johnson, who was the state's military governor, supported it. But other important Unionists, like T. A. R. Nelson, opposed it. They thought it would make the war last longer. By mid-1863, Lincoln wanted Johnson to hold elections in Tennessee. However, Johnson hesitated because he worried that Unionists who opposed the Proclamation would win. These "Conservative Unionists" became very frustrated with Johnson.

At Johnson's request, the East Tennessee Convention met again at the Knox County Courthouse in Knoxville on April 12, 1864. This date was chosen because it was the third anniversary of the attack on Fort Sumter. The purpose was to discuss Lincoln's ten percent plan. This plan allowed former Confederate states to rejoin the Union if 10% of their pre-war voters swore loyalty and promised to support emancipation. Only 160 representatives from 23 counties attended, much fewer than the first two meetings.

The April 1864 meeting was full of arguments. Johnson started by speaking against slavery. But it quickly became clear that Conservative Unionists, led by Nelson, John Baxter, Frederick Heiskell, and William B. Carter, were the majority. Those who supported emancipation, led by Brownlow and Daniel C. Trewhitt, called for "immediate and unconditional emancipation" and for Black soldiers to be armed. They supported Lincoln for president. The Conservative Unionists supported General George McClellan for president and wanted to be lenient with former Confederates.

The arguments became very personal. Baxter was heavily criticized for having taken an oath to the Confederacy. Heiskell accused Brownlow of betraying the South over slavery. After four days, with no agreement possible, Sam Milligan successfully suggested that the Convention end without resolving the debate.

After the War

Andrew Johnson, who had been Tennessee's military governor since 1862, was elected Vice President in November 1864. He became president after Lincoln was killed in April 1865. William "Parson" Brownlow, a Convention representative, was elected Governor of Tennessee in January 1865. More than a dozen former representatives served in the state legislature after the war. These included Alfred Cate, William Mullenix, Beriah Frazier, Wilson Duggan, Charles Inman, and Stephen Matthews. Samuel R. Rodgers served as Speaker of the Tennessee Senate, and William Heiskell served as Speaker of the Tennessee House of Representatives.

The state government, which was controlled by Unionists, was deeply divided after the war. There were "Conservative Republicans" who were allies of Andrew Johnson. They wanted things to return to how they were before the war, but with slavery ended. Then there were the Radical Republicans, allies of Brownlow. They wanted civil rights for Black people and punishment for former Confederates. The Conservatives were outnumbered and used tactics to stop the Radicals' plans, leading to frequent disagreements in the legislature. Despite these divisions, the state government approved the Thirteenth and Fourteenth amendments to the U.S. Constitution. This made Tennessee the first former Confederate state to rejoin the Union in 1866.

Dewitt Clinton Senter, a Convention representative, became governor after Brownlow. He worked to restore the rights of former Confederates. At the state's 1870 meeting to write its current constitution, former East Tennessee Convention representative John Baxter led the committee that wrote the document's Declaration of Rights. Other former representatives were also at this meeting.

Many East Tennessee Convention members were elected or appointed to higher offices. After being governor, Brownlow served in the U.S. Senate. David T. Patterson, another representative, also served in the Senate. Leonidas C. Houk, William Crutchfield, William McFarland, Roderick R. Butler, and Horace Maynard served in Congress. Maynard also became U.S. Postmaster General. Baxter and Connally Trigg became federal judges. James W. Deaderick became Chief Justice of the Tennessee Supreme Court. Several former representatives, including Oliver Perry Temple, David K. Young, and Daniel C. Trewhitt, served as state court judges.

Thomas William Humes, who gave the opening speech at the first Convention meeting, became president of East Tennessee University after the war. He oversaw its change into the University of Tennessee in the 1870s. John J. Craig, a representative from Knox County, was very important in developing the Tennessee marble industry in the late 1800s.

The East Tennessee Convention has not been covered in great detail in many Civil War history books. However, some historians and friends of the Convention members wrote about it. Oliver Perry Temple, who was a key figure at the Convention and had the secretary's notes, wrote a detailed description of the Convention in his book, East Tennessee and the Civil War (1898). He also wrote biographies of several Convention representatives. More recently, Charles F. Bryan, Jr., wrote an article about the Convention in 1980.

Who Were the Delegates?

In 1980, historian Charles F. Bryan, Jr., studied a group of East Tennessee Convention representatives. He found that while the representatives included merchants, lawyers, doctors, ministers, and craftspeople, most were "moderately wealthy" farmers. Most of the Convention's leaders were lawyers or politicians. About three-quarters of the representatives studied were over 40 years old. About 41% of them owned enslaved people, though most owned fewer than five. The wealthiest representative was Knoxville lawyer John Baxter.

Most of the East Tennessee Convention representatives were former Whigs. However, some were Democrats, including Andrew Johnson's sons and son-in-law, along with James G. Spears, William J. Clift, George W. Bridges, and Richard M. Edwards. While most had never held political office, the Convention did include three who had served in the U.S. Congress (T. A. R. Nelson, Thomas D. Arnold, and Horace Maynard) and a former state attorney general. At least two dozen representatives had served in the state legislature, and three were currently serving in the legislature.

Images for kids

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |