West Virginia in the American Civil War facts for kids

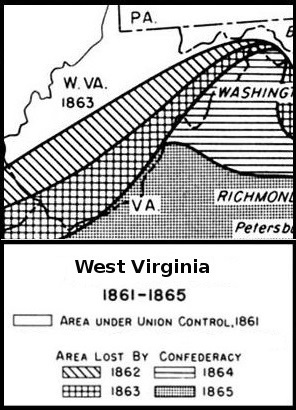

The U.S. state of West Virginia was created from western Virginia and joined the Union during the American Civil War. It was the only state formed by breaking away from a Confederate state. In the summer of 1861, Union soldiers, led by General George McClellan, pushed back Confederate troops under General Robert E. Lee. This allowed Union supporters in northwestern Virginia to form their own government, known as the Restored Government of Virginia, after the Wheeling Convention. Even though this government claimed to rule all of Virginia, its main goal was to create a separate state.

After General Lee left, western Virginia was still attacked by Confederate forces. Both the Confederate and Virginia state governments in Richmond did not accept West Virginia becoming a state in 1863. They saw military actions there as efforts to free their own territory from an illegal government in Wheeling. However, because the Confederacy was struggling for resources, their actions in "western Virginia" focused more on getting supplies and attacking the important Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. This railroad connected the Northeast with the Midwest. The Jones–Imboden Raid is a good example of this. Guerrilla warfare also happened in the new state, especially in the Allegheny Mountain areas to the east. In these areas, people were more divided in their loyalties than in the strongly Unionist northwest. Despite these challenges, the Confederacy could never truly take control of West Virginia from the Union.

Contents

How West Virginia Became a State

Important Political Steps

On April 17, 1861, Virginia's state meeting in Richmond decided to leave the Union. Almost all the delegates from counties west of the Allegheny Mountains voted against this. Most people and leaders in that area refused to follow orders from the new pro-secession government.

On May 15, Union supporters from western Virginia held their first meeting, called the Wheeling Convention. Many people there were not officially chosen, so they just spoke out against leaving the Union. They then called for a proper election of delegates. The elected delegates met again on June 11. On June 20, this Convention declared that the officials in Richmond had given up their jobs by supporting secession. The Convention then chose new people for these state jobs, creating the Restored Government of Virginia.

This "Restored" government was supported in areas that opposed secession. Union troops also controlled three northern counties in the Shenandoah Valley. Even though most people there supported the Confederacy, these counties were also managed by the "Restored" government.

At the Wheeling Convention, some people wanted to create a new state right away. But others pointed out that the U.S. Constitution said Virginia had to agree to a new state being formed from its land. So, they needed the Restored Government of Virginia to give that permission, which it did on August 20, 1861.

In October 1861, people voted to approve becoming a state. A group then met to write a constitution, which was approved by another vote in April 1862. The U.S. Congress approved statehood that December, but only if the new state would slowly end slavery. This meant they needed another meeting to change the constitution and another vote, which was approved.

On June 20, 1863, the new state of West Virginia officially joined the Union. It included all the western counties and the northern part of the Shenandoah Valley, known as the "panhandle."

Before the war, all northern states had free public schools, but the border states did not. West Virginia started its own public school system in 1863. Even with strong disagreement, it set up schools that were almost equal for black children, most of whom had been slaves.

When Union troops took over parts of eastern Virginia like Alexandria and Norfolk, these areas were technically controlled by the Restored Government. However, they were not included in West Virginia. After West Virginia became a state, the Restored Government moved its base to Alexandria.

The pro-Confederate government in Richmond still claimed all of Virginia's old borders. It used Virginia's 1851 constitution to control areas still held by Confederate forces. When West Virginia became a state, this included about thirteen counties that the new state also claimed. Many towns, especially in the southeastern part of the state, sent representatives to both the Wheeling and Richmond state governments.

Slavery in West Virginia

During the Civil War, a Unionist government in Wheeling, Virginia, asked Congress to create a new state from 48 counties in western Virginia. The new state would eventually include 50 counties. The question of slavery in this new state caused delays in getting the bill approved. In the Senate, Charles Sumner did not want a new slave state to join the Union. However, Benjamin Wade supported statehood if a plan for slowly ending slavery was added to the new state's constitution. Two senators represented the Unionist Virginia government: John S. Carlile and Waitman T. Willey. Senator Carlile argued that Congress could not force West Virginia to end slavery. Willey then suggested a compromise: an amendment to the state constitution that would gradually abolish slavery. Sumner tried to add his own amendment, but it failed. The statehood bill, with Willey's amendment, passed both parts of Congress. President Lincoln signed the bill on December 31, 1862. Voters in western Virginia approved the Willey Amendment on March 26, 1863.

President Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. This order freed slaves in Confederate states but did not apply to the border states (four slave states loyal to the Union) or some Union-controlled areas within Confederate states. Two more counties, Berkeley and Jefferson, were added to West Virginia in late 1863. Slaves in Berkeley were also exempt from the Emancipation Proclamation, but those in Jefferson County were not. In 1860, the 49 counties that were exempt had about 6,000 slaves over 21 years old who would not have been freed. This was about 40% of the total slave population. The Willey Amendment only freed children, either at birth or as they grew older, and it stopped the import of new slaves.

West Virginia became the 35th state on June 20, 1863. It was the last slave state to join the Union. Eighteen months later, the West Virginia legislature completely ended slavery. It also approved the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution on February 3, 1865, which abolished slavery nationwide.

Military Actions

In April 1861, Virginia troops led by Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson took control of Harpers Ferry and part of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad that went into western Virginia. On May 23, they seized many B&O trains and railcars.

In May and June 1861, Confederate forces moved into western Virginia to try and take control for the Richmond government and the Confederacy. They could not get past Philippi because the roads were so bad. Then, Union troops under McClellan pushed them back in July.

More fighting happened further south, where Greenbrier County supported the Confederacy. This allowed Confederate troops to enter Nicholas County to the west. In September 1861, Union troops drove the Confederates out of Nicholas County and defeated their counterattack at Cheat Mountain.

After this, most of the area west of the Alleghenies was firmly under Union control, except for the southern and eastern counties. Greenbrier County was taken by Union forces in May 1862. Pro-Confederate guerrillas burned and robbed in some areas. They were not fully stopped until after the war ended.

There were two smaller Confederate attacks against the northeastern part of West Virginia later on: Jackson's Romney Expedition in January 1862, and the Jones–Imboden Raid in May–June 1863.

The Union's plan for the region was to protect the important B&O Railroad. They also wanted to attack eastward into the Shenandoah Valley and southwestern Virginia. This second goal was very hard to achieve because of the bad roads across the mountains.

The B&O Railroad crossed the northern end of the Shenandoah Valley, east of the Alleghenies. So, Union troops occupied this area for almost the entire war, and there was frequent fighting there.

Harpers Ferry was home to a major U.S. Army weapons factory. Confederates took it in the first days of the war, and again during the Maryland Campaign of 1862. During the Maryland Campaign, it was a path for the Army of Northern Virginia to invade and retreat. The campaign ended there with the Battle of Shepherdstown.

Many soldiers from West Virginia fought on both sides during the war. Those who fought for the Confederacy were in "Virginia" regiments. Those who fought for the Union were also in "Virginia" regiments until West Virginia became a state. Then, several Unionist "Virginia" regiments were renamed "West Virginia" regiments. These included the 7th West Virginia Infantry, famous for fighting at Antietam and Gettysburg. The 3rd West Virginia Cavalry also fought at Gettysburg.

On the Confederate side, Albert G. Jenkins, a former U.S. Representative, formed a cavalry brigade in western Virginia. He led it until he died in May 1864. Other western Virginians served under Brig. Gen. John D. Imboden and in the Stonewall Brigade under Brig. Gen. James A. Walker.

Guerrilla Warfare in West Virginia

On May 28, 1861, one of the first trials of the Civil War for sabotage happened in Parkersburg, Virginia. A group of men were found playing cards under a B&O railroad bridge and were arrested by Federal authorities. The trial was led by Judge William Lowther Jackson (who later became a Confederate General). The men were found not guilty because no actual crime had happened. But Parkersburg was divided over the decision, and Judge Jackson left to join Confederate forces.

After Confederate forces were defeated at the Battle of Philippi and the Battle of Cheat Mountain, they only sometimes occupied parts of western Virginia. Local people who supported Richmond were left to fight on their own. Many guerrilla groups started from pre-war local militias. These were called Virginia State Rangers, and starting in June 1862, they became part of Virginia State Line regiments. By March 1863, many of them joined the regular Confederate army.

However, there were others who fought without permission from the Richmond government. Some fought for the Confederacy, while others were just bandits who attacked both Union and Confederate supporters. Early in the war, captured guerrillas were sent to prisons like Camp Chase or Johnson Island in Ohio, Fort Delaware in Delaware, and also the Atheneum in Wheeling. Some were released after promising to be loyal, but many went back to their guerrilla activities. Union authorities started their own guerrilla groups. The most famous was the "Snake Hunters," led by Captain Baggs. They patrolled Wirt and Calhoun counties through the winter of 1861–62 and captured many Moccasin Rangers, sending them as prisoners to Wheeling.

The fight against rebel guerrillas changed under General John C. Frémont and Colonel George Crook. Colonel Crook took command of the 36th Ohio Infantry, based around Summersville, Nicholas County. He trained his soldiers in guerrilla tactics and decided not to take prisoners.

On January 1, 1862, Crook led his men north to Sutton, Braxton County, where he thought Confederate forces were. They found none, but his troops faced strong guerrilla resistance. In response, they burned houses and towns along their path. But by August 1862, Union efforts were greatly hurt when troops were moved to eastern Virginia.

With fewer Union troops, General William W. Loring, C.S.A., recaptured the Kanawha Valley. General Albert Gallatin Jenkins, C.S.A., moved his forces through central West Virginia, taking many supplies and prisoners. More people joined the Confederate army, and General Loring even opened recruitment offices as far north as Ripley.

In response to rebel attacks, General Robert H. Milroy demanded that money be paid for damages. He started fining citizens of Tucker County, whether they were guilty or not, and threatened to burn their houses. Jefferson Davis and Confederate leaders formally complained to General Henry Halleck in Washington, who criticized General Milroy. However, Milroy defended his actions and was allowed to continue his policy.

By early 1863, Union efforts in West Virginia were not going well. Union supporters were losing trust in the Wheeling government to protect them. As Virginia was about to be split into two states, guerrilla activity increased to try and stop new county governments from forming. By 1864, some central counties had become more stable, but guerrilla activity was never fully stopped. Union forces that were needed elsewhere were stuck in West Virginia, which many soldiers saw as a less important part of the war. But Federal forces could not ignore any rebel territory, especially one so close to the Ohio River.

As late as January 1865, Governor Arthur I. Boreman complained about widespread guerrilla activity as far north as Harrison and Marion counties. The Wheeling government could only control about 20 to 25 counties in the new state. In one last bold act of the guerrilla war, McNeill's Rangers from Hardy County kidnapped Generals George Crook and Benjamin Franklin Kelley from behind Union lines. They delivered them as prisoners of war to Richmond. The Confederate surrender at Appomattox finally ended the guerrilla war in West Virginia.

Soldiers from West Virginia

On May 30, 1861, Brig. Gen. George B. McClellan in Cincinnati wrote to President Lincoln: "I am sure that many volunteers can be raised in Western Virginia..." After almost two months fighting in West Virginia, he was less hopeful. He wrote to Governor Francis Harrison Pierpont of the Restored Government of Virginia in Wheeling that he and his army wanted to help the new government. But he said they would eventually be needed elsewhere, and he urged that troops be raised "among the people." He added, "Before I left Grafton I asked for weapons, clothing, etc., for 10,000 Virginia troops – I fear that my estimate was much too large." On August 3, 1861, the Wellsburg "Herald" newspaper wrote, "Northwestern Virginia is in a pretty state to become a separate state... after all the talk and excitement about a separate state, she has actually formed only four incomplete regiments of soldiers, and one of these is almost entirely from the Panhandle."

Confederate leaders faced similar problems at the start of the war. On May 14, 1861, Colonel George A. Porterfield arrived in Grafton to find volunteers, and he reported that enlistment was slow. Colonel Porterfield's main problem was a lack of support from the Richmond government, which did not send enough guns, tents, and other supplies. He eventually had to turn away hundreds of volunteers because he lacked equipment. General Henry A. Wise also complained about recruitment in the Kanawha Valley, though he eventually gathered 2,500 infantry, 700 cavalry, and three artillery groups for a total of 4,000 men. This group became known as "Wise's Legion." One regiment from Wise's Legion, the 3rd Infantry (later called the 60th Virginia Infantry), was sent to South Carolina in 1862. It was from Major Thomas Broun of the 3rd Infantry that General Robert E. Lee bought his famous horse, Traveller.

In April 1862, the Confederate government started a military draft, and almost a year later, the U.S. government did the same. The Confederate draft was not very effective in West Virginia because the Virginia state government had broken down in the western counties, and Union forces occupied the northern counties. However, conscription did happen in the southern counties. In the southern and eastern counties of West Virginia, Confederate recruitment continued until at least early 1865.

The Wheeling government asked to be excused from the Federal draft, saying they had already provided more than their share of soldiers. An exemption was given for 1864, but in 1865, a new demand for troops was made, which Governor Boreman struggled to fill. In some counties, former Confederates suddenly found themselves joining the U.S. Army.

The loyalty of some Federal troops was questioned early in the war. The quick Union takeover of northern West Virginia had trapped many Southern sympathizers behind Union lines. Letters to General Samuels and Governor Pierpoint in the Dept. of Archives and History in Charleston, mostly from 1862, show the concern of Union officers. Colonel Harris, 10th Company, wrote on March 27, 1862, to Governor Pierpoint: "The election of officers in the Gilmer County Company was a joke. The men elected were rebels and bushwhackers. The election of these men was surely meant as a mockery of the militia's reorganization."

Because the Richmond government did not keep separate military records for what would become West Virginia, there has never been an official count of Confederate soldiers from West Virginia. Early estimates were very low. In 1901, historians Fast & Maxwell put the number at about 7,000. One exception to the low estimates is found in Why The Solid South?, whose authors believed the Confederate numbers were higher than Union numbers. In later histories, the estimates grew. Otis K. Rice put the number at 10,000-12,000. Richard O. Curry in 1964 estimated 15,000. The first detailed study of Confederate soldiers estimated the number at 18,000, which is close to the 18,642 figure given by the Confederate Dept. of Western Virginia in 1864. In 1989, a study by James Carter Linger estimated the number at nearly 22,000.

The official number of Union soldiers from West Virginia is 31,884, as stated by the Provost Marshal General of the United States. However, these numbers include soldiers who re-enlisted and soldiers from other states who joined West Virginia regiments. In 1905, Charles H. Ambler estimated the number of native Union soldiers to be about 20,000.

Richard Current estimated the number of native Union soldiers at 29,000. However, in his calculations, he only subtracted 2,000 soldiers from other states in West Virginia regiments. Ohio contributed nearly 5,000, with about 2,000 from Pennsylvania and other states.

In 1995, the George Tyler Moore Center for the Study of the Civil War began counting soldiers from all regiments that included West Virginians, both Union and Confederate. They concluded that West Virginia contributed approximately 20,000-22,000 men to both the Union and Confederate armies.

Nursing During the Civil War

The Sisters of St. Joseph, who ran Wheeling Hospital in that city, served as nurses during the war. They cared for soldiers brought to the hospital and prisoners at the Atheneum in downtown Wheeling. In 1864, the Union army took control of the hospital. That summer, the sisters began working for the federal government as matrons and nurses. Several of them later received pensions for their service.

Civil War Battles in West Virginia

The Manassas Campaign:

- Battle of Hoke's Run (July 2, 1861), Berkeley County – Stonewall Jackson successfully slowed down a larger Union force.

The Western Virginia Campaign:

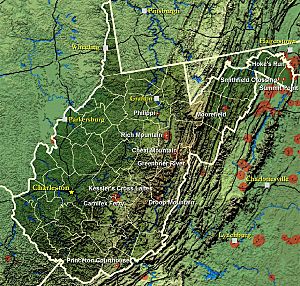

- Battle of Philippi (June 3, 1861), Barbour County – A Union victory that made George McClellan famous.

- Battle of Laurel Hill (July 7–11, 1861), Barbour County – Union forces defeated Confederates in 5 days of small fights at Belington. This was a distraction for the Battle of Rich Mountain.

- Battle of Rich Mountain (July 11, 1861), Randolph County – Another McClellan victory that led to him getting a higher command.

- Battle of Corrick's Ford (July 13, 1861), Tucker County – Confederate Brig. Gen. Robert S. Garnett was the first general officer killed in the war.

- Battle of Kessler's Cross Lanes (August 26, 1861), Nicholas County – Confederates defeated a Union force; General Lee arrived soon after.

- Battle of Carnifex Ferry (September 10, 1861), Nicholas County – Union General Rosecrans pushed back the Confederates and gained more land.

- Battle of Cheat Mountain (September 12–15, 1861), Pocahontas County – General Lee was defeated and called back to Richmond.

- Battle of Greenbrier River (October 3, 1861), Pocahontas County – An undecided fight that caused bloodshed but no clear winner.

- Battle of Scary Creek (July 17, 1861), Putnam County, West Virginia - A small battle fought during the American Civil War near present-day Nitro.

- Battle of Guyandotte (November 10–11, 1861), Cabell County– Confederate cavalry attacked the town and a small, untrained Union force. In return, the Union burned much of the town the next day.

- Battle of Camp Allegheny (December 13, 1861), Pocahontas County – A Union attack was pushed back, and both sides stayed in camp for the winter.

Later Actions:

- Battle of Hancock (January 5–6, 1862), Morgan County – Stonewall Jackson's operations against the B&O Railroad.

- Battle of the Henry Clark House (May 1, 1862), Mercer County, West Virginia – Part of Stonewall Jackson's Shenandoah Valley Campaign. Union General Cox's actions against Princeton and the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad at Dublin, Virginia.

- Battle of Princeton Court House (May 16–18, 1862), Mercer County, West Virginia – Part of Jackson's Shenandoah Valley Campaign. Union General Cox's actions against the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad at Dublin, Virginia.

- Battle of Harpers Ferry (September 12–15, 1862), Jefferson County – Jackson surrounded the town and forced its soldiers to surrender.

- Battle of Charleston (September 13, 1862), Kanawha County – Confederates took Charleston and occupied it for six weeks.

- Battle of Shepherdstown (September 19–20, 1862), Jefferson County – A. P. Hill's counterattack helped General Lee's army retreat safely from Sharpsburg.

- Battle of Hurricane Bridge (March 28, 1863), Putnam County – A small fight between Union and Confederate forces.

- Battle of White Sulphur Springs (August 26–27, 1863), Greenbrier County, West Virginia – Colonel George Patton stopped a Union raid against Lewisburg.

- Battle of Bulltown (October 13, 1863), Braxton County, West Virginia – A Union military post held strong against a Confederate attack.

- Battle of Droop Mountain (November 6, 1863), Pocahontas County – After this Union victory, Confederate resistance in the state mostly ended.

- Battle of Moorefield (August 7, 1864), Hardy County – Union cavalry drove off John McCausland's Confederate cavalry and captured almost 500 men.

- Battle of Summit Point (August 21, 1864), Jefferson County – An undecided action during Union Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan's Shenandoah Valley Campaign.

- Battle of Smithfield Crossing (August 25–29, 1864), Jefferson and Berkeley counties – Undecided. Two of Jubal Early's infantry divisions pushed back a Union cavalry division but were stopped by an infantry counterattack.

Important West Virginians in the Civil War

- Union

- Francis H. Pierpont, "Father of West Virginia" - Governor of West Virginia (reorganized government) from Monongalia County (1861-1863).

- Arthur I. Boreman - Governor of West Virginia from Tyler County (1863-1869).

- Isaac H. Duval - Brigadier General and politician from Wellsburg (Brooke County).

- Nathan Goff Jr. - Major from Clarksburg (Harrison County), later became Secretary of the Navy and Governor of West Virginia.

- Thomas M. Harris - Brigadier General from Harrisville (Ritchie County).

- Daniel D. Johnson - Colonel (infantry) and Senator from Tyler County.

- Benjamin F. Kelley - Brigadier General living in Wheeling.

- George R. Latham - Colonel (infantry) and Congressman living in Grafton (Taylor County).

- Fabricius A. Cather - Major (1st West Virginia Cavalry) from Taylor County.

- Joseph A.J. Lightburn - Brigadier General from Lewis County.

- Jesse L. Reno - Major General from Wheeling.

- David H. Strother - Colonel (cavalry) from Martinsburg (Berkeley County).

- William B. Curtis - Colonel (12th West Virginia Infantry), later a Brevet Brigadier General, from Putnam County.

- Joseph Thoburn - Irish-born Colonel (infantry) from Wheeling.

- John Hinebaugh - Second Lieutenant (6th West Virginia Cavalry) from Preston County.

- John Witcher - Brevet Brigadier General (cavalry) from Cabell County, later became a U.S. Congressman.

- James F. Ellis - Corporal (15th West Virginia Infantry) from Lewis County.

- Joseph Snider - Colonel (infantry) from Monongalia County.

- Martin R. Delany - Major (104th regiment of the United States Colored Troops) from Jefferson County.

26 Medals of Honor were given to West Virginians for their actions during the war. Another 6 medals were awarded to West Virginians who moved and served in regiments from other states. The 1st West Virginia Cavalry received a total of 14 medals, making it one of the most honored regiments in the Union Army.

- Confederate

- Belle Boyd - A female spy who gave information to the Confederate States Army.

- Allen T. Caperton - One of the Confederate Senators for Virginia, later a U.S. Senator for West Virginia, from Monroe County.

- Raleigh E. Colston - Brigadier General living in Berkeley County.

- Charles J. Faulkner - Lieutenant Colonel, U.S. Congressman, and diplomat who was held as a prisoner early in the war.

- Birkett D. Fry - Brigadier General and former adventurer from Kanawha County.

- John Echols - Brigadier General from Monroe County, commander of the Dept. of Western Virginia, who led a brigade with many West Virginia soldiers.

- George M. Edgar - Lt. Colonel and founder of Edgar's Battalion. He later became president of a university that would be named University of Arkansas and a seminary that became Florida State University.

- Walter Gwynn - Brigadier General from Jefferson County.

- William Lowther Jackson - Brigadier General and former Lt. Governor from Clarksburg (Harrison County).

- Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson - Lieutenant General from Clarksburg (Harrison County).

- Albert G. Jenkins - Brigadier General and former U.S. Congressman from Cabell County, who led a brigade of western Virginia cavalrymen.

- John McCausland - Brigadier General living in Point Pleasant (Mason County).

- John Hanson McNeill - Captain and partisan commander from Moorefield (Hardy County).

- Alexander W. Monroe - Colonel and politician from Hampshire County.

- John Q.A. Nadenbousch - Colonel (infantry) from Berkeley County.

- Edwin Gray Lee - Brigadier General from Shepherdstown (Jefferson County).

- Charles T. O'Ferrall - Colonel (cavalry) and politician from Berkeley Springs (Morgan County), later became Governor of Virginia.

- George S. Patton Sr. - Lieutenant Colonel from Charleston, who was badly wounded at the Battle of Opequon. He was the grandfather of the famous American World War II general George S. Patton Jr.

- George A. Porterfield - Colonel (infantry) from Berkeley County.

- M. Jeff Thompson - Brigadier General in the Missouri State Guard from Harpers Ferry.