Battle of Droop Mountain facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Droop Mountain |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Pocahontas County, West Virginia |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~ 3,855 | ~ 1,700 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 140 (45 killed, 93 wounded, 2 captured) | 276 (33 killed, 121 wounded, 122 missing) | ||||||

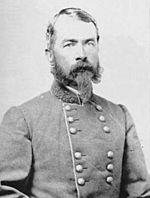

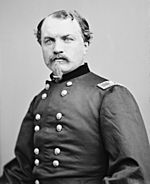

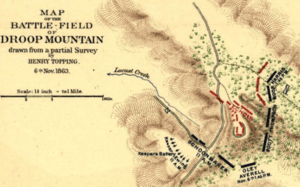

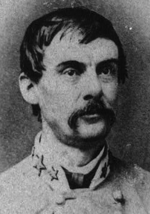

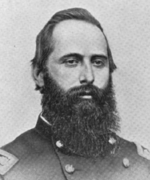

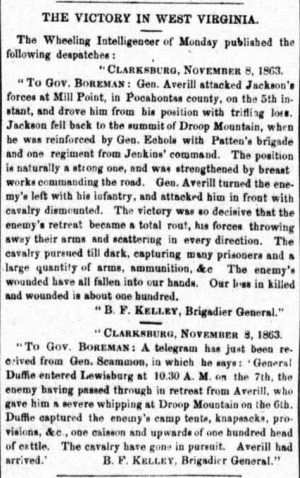

The Battle of Droop Mountain happened in Pocahontas County, West Virginia, on November 6, 1863. It was a key fight during the American Civil War. A Union army group, led by Brigadier General William W. Averell, won against a smaller Confederate force. The Confederate troops were commanded by Brigadier General John Echols and Colonel William L. "Mudwall" Jackson.

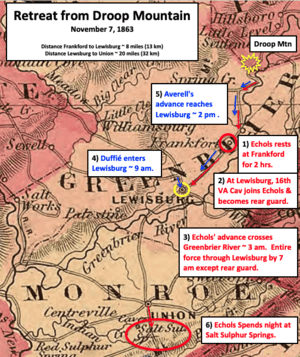

The battle forced the Confederates off their defenses on Droop Mountain. They lost many weapons and supplies. They quickly escaped south through Lewisburg, West Virginia. This happened just hours before another Union force arrived to take the town.

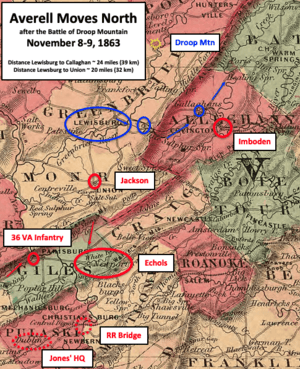

The Battle of Droop Mountain was one of the biggest battles in West Virginia during the war. Averell won a clear victory. However, he did not achieve all his goals. He wanted to destroy the Confederate army in Lewisburg and damage the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad. Lewisburg, which supported the Confederacy, was captured. But the Confederate army got away and returned weeks later. The railroad was not seriously attacked. After this trip, Averell moved north. The other Union commander, Duffié, went back toward Charleston.

Some historians say this battle ended organized Confederate fighting in West Virginia. After it, most battles in the region moved east. They happened in the Shenandoah Valley and West Virginia's eastern panhandle. Other historians think the battle was a tactical victory for Echols and Jackson. This is because Averell did not wipe out the Confederate army in Lewisburg. More importantly, he did not harm the railroad.

Contents

Why Did the Battle of Droop Mountain Happen?

West Virginia's Role in the Civil War

On April 17, 1861, Virginia decided to leave the United States. This was called the Virginia Secession Convention. Most people in the northwestern part of Virginia wanted to stay loyal to the United States. They met and decided to form their own state government. This new government was in Wheeling.

West Virginia officially became a state on June 20, 1863. But even after this, Confederate soldiers were still active there. Not everyone in the new state supported the Union. The state also had problems with bushwhackers and Partisan rangers. These groups fought using guerrilla warfare. Historians believe that West Virginia provided about 20,000 to 22,000 soldiers to each side of the war. Lewisburg, near the Virginia border, was a town that supported the Confederacy. It saw several small battles and skirmishes during the war.

West Virginia had tough land, few good roads, and not many towns. Its people were also poor. A key asset for the Union Army was the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. This railroad ran through northern West Virginia. The Confederate Army often attacked it. So, Union troops were needed to protect the railroad. Union leaders usually saw their troops in West Virginia as a defense force. They were there to stop Confederate raids and fight guerrillas.

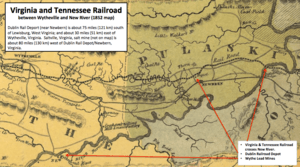

Railroads were very important for fighting in West Virginia. The Union had the B&O Railroad in the north. The Confederacy had the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad in Virginia. This railroad was close to West Virginia's southern border. The Confederacy used it to move soldiers and supplies. It connected to other railroads in Lynchburg, Virginia and Bristol, Tennessee. It also had telegraph lines. Important salt and lead mines were along its route near Wytheville, Virginia. The lead mine provided about one-third of the lead for Confederate bullets. Union forces from West Virginia often tried to raid this railroad.

Union Plans to Attack the Railroad

Brigadier General Benjamin Franklin Kelley was the Union Army commander for West Virginia. He reported to General-in-Chief Henry Halleck. Halleck wanted the Confederates out of Lewisburg. He also wanted the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad to be destroyed.

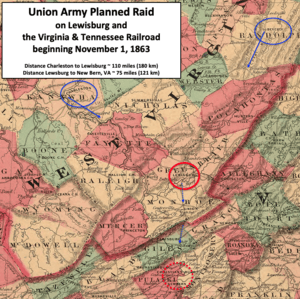

On October 23, 1863, Kelley ordered Averell to move his troops south. Averell's mission was to attack a Confederate force near Lewisburg. Droop Mountain was not part of the original plan. The main goal was to capture or drive away Confederate forces in Lewisburg. A second Union force, led by Brigadier General Alfred N. Duffié, would move from Charleston. They would meet Averell in Lewisburg to help.

After Lewisburg, Averell was supposed to attack the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad. His mounted troops would go further south into Virginia. Their goal was to destroy the railroad bridge over the New River. This bridge was less than 10 miles from the railroad's Dublin Station. Destroying this bridge was a very important goal for Averell's mission. At that time, Confederate Lieutenant General James Longstreet was in Tennessee. Damaging the railroad would make it hard for him to get his troops back east.

Who Fought at Droop Mountain?

Confederate Forces

In November 1863, the Confederate Army controlled much of the Greenbrier Valley in West Virginia. Confederate Major General Sam Jones was in charge of this area. His headquarters were about 75 miles south of Lewisburg, at the Dublin Rail Depot in Virginia. Jones was not at the battle, but the soldiers and land were his responsibility.

Brigadier General John Echols led a group of soldiers based in Lewisburg. Colonel William L. "Mudwall" Jackson had a small cavalry group. They patrolled the Huntersville-Hillsboro area of West Virginia. Brigadier General Albert G. Jenkins was recovering from a wound. But two of his regiments and a battery were in the Greenbrier County area. Colonel Milton J. Ferguson temporarily led Jenkins' group.

Union Forces: Averell's Brigade

Averell's 4th Separate Brigade left Beverly on November 1, 1863. Many of his soldiers knew the area well. They had been defeated there a few months earlier. Averell's group had two infantry regiments, three mounted infantry regiments, one cavalry regiment, and two light artillery batteries.

The infantry regiments were the 10th West Virginia and the 28th Ohio. The mounted infantry regiments were the 2nd West Virginia, 3rd West Virginia, and 8th West Virginia. Colonel Augustus Moor often led the infantry. Colonel John H. Oley usually led the mounted infantry. Averell's cavalry was the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment. It was led by Colonel James M. Schoonmaker. Averell's brigade had about 3,855 officers and soldiers ready for duty.

Union Forces: Duffié's Command

The mounted part of Scammon's force, led by Brigadier General Alfred N. Duffié, left Charleston for Lewisburg on November 3. It had 970 officers and men with 1,025 horses. It included the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry Regiment, the 34th Ohio Mounted Infantry Regiment, and Simmonds' Battery. Most of these soldiers knew Lewisburg, which was about 110 miles away.

On November 4, Duffié was slowed down by many roadblocks. He even had to dig new roads around them. Two infantry regiments joined Duffié's mounted men on November 5.

How the Battle Started

First Contact and Averell's Trap

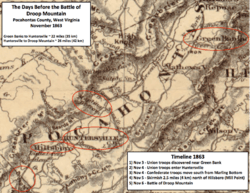

In the first few days, Averell's Brigade moved south. They met small groups of guerrillas and Confederate soldiers. On November 3, a small group of Averell's soldiers was found near Green Bank. They were discovered by about 350 men from the 19th Virginia Cavalry. After a small fight, Averell's soldiers rejoined his main force.

The Confederate commander, Colonel Jackson, learned about Averell's troops. He warned other Confederate groups. Jackson's small group needed more soldiers. Averell and Jackson now knew they were close to each other.

Averell continued his march south on November 4. He burned two enemy camps. He found no enemy troops in Huntersville. He learned that part of the 19th Virginia Cavalry was 6 miles west. Averell planned to cut them off from their headquarters. He sent Colonel Schoonmaker and the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry to block a road. Their goal was to stop the Confederates from reaching Mill Point and Hillsboro.

However, the Confederates learned about Averell's plan. Colonel Arnett and the 20th Virginia Cavalry left Marling Bottom for Mill Point. They set up roadblocks as they went. Averell's trap failed. The Confederates got to Mill Point safely.

Fighting at Mill Point

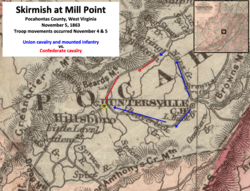

That evening, Jackson's Confederates took up defensive spots near Stamping Creek. Schoonmaker's Union troops were on the other side of the creek. The two groups were close enough to see each other.

Early on November 5, Averell moved his infantry toward Mill Point. Oley also moved his troops there. Schoonmaker's troops were fighting Jackson's two regiments. Jackson also used his two howitzers (small cannons). Schoonmaker had no artillery, which made it hard for him. Oley heard the cannons and hurried his mounted regiments and battery to help. When Oley arrived, he placed his cannons between the two forces.

Jackson knew the Union had more soldiers and better cannons. He decided to fall back to Droop Mountain. This mountain was just south of Hillsboro. Jackson's men moved to the top of the mountain, using the forest for cover. Union soldiers stopped fighting around 2:00 pm. Averell reported that there was "trifling loss on either side."

Confederates Get Ready

When Jackson and Arnett reached Droop Mountain on November 5, they set up defenses. Jackson had about 750 men. He could see Union Army camps around Hillsboro.

Brigadier General Echols decided to send more help to Jackson. He was worried another Union force might attack from the west. (Duffié was indeed coming from the west.) Echols marched halfway to Droop Mountain on November 5. He camped near the Greenbrier River. That evening, more Confederate soldiers arrived at Droop Mountain to help Jackson. At 2:00 am on November 6, Echols continued his march. He sent a group of soldiers to block a road. He feared Union soldiers might use it to attack Jackson's side.

The Battle of Droop Mountain

Averell's Plan of Attack

Averell woke up early on November 6 to plan his attack. He started moving his troops from Mill Point to Hillsboro after sunrise. He sent out small groups of soldiers to confuse the Confederates. As the Confederates fell back to the mountain, Averell looked at the land. He saw that a direct attack would be a disaster.

So, he planned a three-sided attack. Part of his troops on the left would distract the Confederates. A large group would attack the enemy from the right side. Finally, more troops would attack from the front and right. Colonel Augustus Moor started the flanking move after 9:00 am with 1,175 men. His force included the 10th West Virginia Infantry and the 28th Ohio Infantry. Moor's group took a long, hidden route. This would put them on the enemy's left side. Schoonmaker and the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry moved to the left (Confederate right). They used their artillery to get the attention of Jackson's men.

Echols Takes Command

Brigadier General Echols arrived at Droop Mountain with more soldiers around 9:00 am on November 6. He brought Colonel Ferguson and more troops. Their arrival was met with loud "rebel yells" and music. This made sure both sides knew about the reinforcements. Echols took command of all the Confederate forces.

Echols placed his cannons near Jackson's howitzers. He put his soldiers in defensive positions. The total Confederate force in the battle was about 1,700 men. Echols commanded the Confederate right side. Jackson commanded the center.

The Battle Begins

Some small fights had already happened. But historians say the battle truly began around 11:00 am. This is when Schoonmaker's artillery fired at Droop Mountain. Cannons fired all day. But the Union cannons could not hit the enemy artillery. Confederate artillery was accurate. It eventually killed almost all the horses for one Union battery.

By noon, Schoonmaker realized he could not hit enemy artillery. He pulled back some of his cannons to save them. Around 1:00 pm, Averell got his men ready for the main attack. His mounted infantry regiments began moving up the mountain. They faced sharpshooters, musket fire from defenses, and cannon fire.

Union Forces Break Through

On the far right (Confederate left), Colonel Moor's troops met the Confederate flank around 1:45 pm. The 28th Ohio Infantry led the way. They were surprised by a charge from Confederate cavalry. This pushed the 28th Ohio Infantry back. The Confederate commander asked Echols for more help. Echols sent 300 men and two cavalry companies. Moor ordered his Ohio soldiers to lie down and fire. Colonel Thomas M. Harris and the 10th West Virginia Infantry moved to the front. They began pushing the outnumbered enemy back.

Averell decided it was time for the attack in the center. His three mounted infantry regiments advanced up the mountain. They faced heavy fire. The 3rd West Virginia Infantry made the most progress. They found Moor's left flank. Echols now faced five Union regiments on his left and center.

The Confederate center was strongly defended. But when the Union regiments reached the defenses, the fighting became hand-to-hand. Confederate soldiers used their empty muskets as clubs. Eventually, the Confederates retreated. The 2nd West Virginia Infantry was the first to enter the Confederate defenses. They had the most casualties of the three regiments in the center attack.

The Confederates on the far left were being pushed back. This created a dangerous angle in their line. Echols moved more troops to the left and center. This slowed the Union advance for a short time. But it was not enough to stop Moor's attack. The Confederate center and right were also in trouble. Some of Jackson's men began running away. Averell received this news around 3:00 pm. He ordered more cavalry to advance quickly. The battle was mostly over by 4:00 pm. Echols learned that Duffié was only 18 miles west of Lewisburg. With both his left and right sides broken, Echols ordered his troops to fall back.

Retreat and Aftermath

Confederate Retreat

One of the last Confederate officers to leave Droop Mountain was Major Robert Augustus Bailey. He was badly wounded trying to rally his men. His regiment started with 550 men and had 113 casualties. The road to Lewisburg was blocked with cannons, wagons, and horses. The Confederate retreat became very urgent. Soldiers threw away their weapons as they ran. Many ran into the woods. Colonel Patton could not get his men organized until he reached Frankford, 19 miles south of the battle.

Moor's infantry pursued the retreating Confederates. They fired into them from where the Confederate artillery had been. Moor's infantry chased the Confederates for about 6 miles. They stopped after dark to camp. Other Union groups also chased the Confederates.

Lewisburg and the End of the Expedition

Duffié's troops arrived in Lewisburg at 9:00 am on November 7. The Confederate rear guard was just leaving. Most of the Confederate army had passed through two hours earlier. Duffié started a chase but returned to Lewisburg after finding roadblocks and a burned bridge. The Union cavalry captured 110 cattle and a few enemy soldiers. In Lewisburg, the Union captured supplies and equipment. By evening, Echols was in Monroe County, close to the Virginia border.

The chase of Echols ended on November 8. Averell and Duffié seemed to blame each other for stopping. Averell said he stopped because of roadblocks and having too many prisoners. Duffié said Averell ordered him to return. An important reason to stop the chase was that Averell heard more Confederate soldiers were waiting for Echols.

Duffié moved to Meadow Bluff as ordered. But he found the location difficult due to bad weather and supply problems. He returned to Charleston on November 13. Moor and his infantry were sent back to Beverly. Averell moved north with his cavalry and mounted infantry.

Casualties of the Battle

Averell's Union forces had 45 men killed, 93 wounded, and 2 captured. This totals 140 casualties. The 10th West Virginia Infantry and the 28th Ohio Infantry had the most casualties. For the Confederate troops, 33 were killed, 121 wounded, and 122 captured. This totals 276 casualties. The 19th Virginia Cavalry and the 22nd Virginia Infantry had the most casualties.

What Happened After Droop Mountain?

Averell reported that his victory at Droop Mountain was "decisive." He said the enemy's retreat was a "total rout." However, Duffié believed that if Averell had only held the Confederates lightly, they could have captured almost the entire Confederate force. The Confederates knew they would have been trapped if they had stayed on the mountain.

On November 7, Major General Sam Jones reported that Echols was badly defeated. He thought Echols would probably not escape. But by November 15, Jones believed the loss at Droop Mountain was not as bad as he first thought. By December 11, Confederate troops had returned to their original positions.

After the Battle of Droop Mountain, the only major battles in West Virginia were in the Eastern Panhandle. Some historians say Confederate fighting in West Virginia ended after Droop Mountain. However, the Confederates did return to their positions. The fighting may have just moved to the Shenandoah Valley. Some even see Droop Mountain as a tactical victory for Echols. This is because the Confederate army was not destroyed, and the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad was unharmed.

Future Leaders from the Battle

Averell was sometimes criticized for being too careful. He was removed from his command later in 1864. However, Averell was one of the few Union cavalry leaders who won battles in the eastern part of the war before General Philip Sheridan arrived. He won at the Battle of Rutherford's Farm and the Battle of Moorefield.

Averell and Echols were the main generals at Droop Mountain. From the Union side, Harris, Moor, and Oley later became generals. Schoonmaker won the Medal of Honor for a charge in another battle. Harris served on the commission that tried the people involved in the Lincoln assassination. For the Confederates, Jackson later became a general. Patton would have become a general if he had not been wounded in another battle. Patton was the grandfather of the famous World War II tank commander, George S. Patton.

Droop Mountain Today

The battlefield is now a preserved site. It is managed by West Virginia as Droop Mountain Battlefield State Park. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The park opened in 1928. It is West Virginia's oldest state park. Unknown Confederate soldiers who died in the battle are buried in the Confederate Cemetery at Lewisburg. This cemetery is also listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Images for kids

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |