Black Mountains (North Carolina) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Black Mountains |

|

|---|---|

The Black Mountains immersed in a snowstorm

|

|

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Mount Mitchell |

| Elevation | 6,684 ft (2,037 m) |

| Geography | |

| Country | United States |

| State | North Carolina |

| Parent range | Blue Ridge Mountains |

| Geology | |

| Orogeny | Alleghenian |

The Black Mountains are a mountain range in western North Carolina, located in the southeastern United States. They are part of the Blue Ridge Mountains and the larger Appalachian Mountains. These mountains are the tallest in the Eastern United States. They get their name from the dark look of the red spruce and Fraser fir trees that grow on their higher slopes. This dark forest stands out against the lighter green or brown deciduous trees (trees that lose their leaves) found at lower elevations. The Eastern Continental Divide, which separates rivers flowing to the Atlantic from those flowing to the Gulf of Mexico, crosses the southern part of the Black Mountains.

The Black Mountains are home to Mount Mitchell State Park, which protects the highest peak and nearby summits. A large part of the range is also protected by the Pisgah National Forest. The Blue Ridge Parkway, a famous scenic road, runs along the southern edge of the mountains. North Carolina Highway 128 connects the parkway to the top of Mount Mitchell. Most of the Black Mountains are in Yancey County, but some southern and western parts are in Buncombe County.

Contents

Exploring the Geography of the Black Mountains

The Black Mountains form a shape like the letter "J" that opens towards the northwest. The mountains start in the north near Little Crabtree Creek Valley and rise southward to the tall peak of Celo Knob, which is about 6,327 feet (1,928 meters) high. A few miles south of Celo, the crest dips down to about 5,700 feet (1,737 meters) at Deep Gap. Then, it rises steeply again to Potato Hill.

The mountain crest continues south through the central part of the range. This area has 6 of the 10 highest peaks in the eastern United States. This includes Mount Mitchell, the highest, and Mount Craig, the second-highest. South of Mount Mitchell, the crest drops below 6,000 feet (1,829 meters) at Stepp's Gap. It then rises again to about 6,520 feet (1,987 meters) at Mount Gibbes. Near Potato Knob, the Black Mountain crest turns northwest. It then drops to about 5,320 feet (1,622 meters) at Balsam Gap, where it meets the Great Craggy Mountains. The crest then turns north towards Point Misery and Big Butt before going down into the Cane River Valley.

Rivers and Water Flow in the Black Mountains

The northern Black Mountains are drained by the Cane River to the west and the South Toe River to the east. Both of these rivers flow into the Nolichucky River. The southwestern part of the range is drained by the upper French Broad River. Like the Nolichucky, the French Broad River flows west of the Eastern Continental Divide. This means its waters eventually reach the Gulf of Mexico. The southern side of the mountains drains into Flat Creek and the north fork of the Swannanoa River, which also flows into the French Broad River. The North Fork Reservoir, which gets a lot of rain from the southern slopes, is the main water source for the city of Asheville. Some streams in the southeastern part of the range flow into the Catawba River. These rivers are east of the Eastern Continental Divide, so their waters flow towards the Atlantic Ocean.

Tallest Peaks: Notable Summits of the Black Mountains

The main ridge of the Black Mountains is only about 15 miles (24 kilometers) long. But within these 15 miles, there are 18 peaks that rise to at least 6,300 feet (1,900 meters) above sea level. The Black Mountains stand out very clearly from the lower land around them. This is especially true from the eastern side, where they rise over 4,500 feet (1,375 meters) above the Catawba River Valley and Interstate 40. This creates some truly amazing mountain views.

| Mountain | Elevation | General area | Named after |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mount Mitchell | 6,684 ft/2,037 m | North-central Blacks | Elisha Mitchell (1793–1857), a professor and surveyor |

| Mount Craig | 6,647 ft/2,026 m | North-central Blacks | Locke Craig (1860–1925), a North Carolina governor |

| Balsam Cone | 6,611 ft/2,015 m | North-central Blacks | |

| Cattail Peak | 6,583 ft/2,006 m | North-central Blacks | Possibly named for mountain lions that may have once lived there |

| Big Tom | 6,581 ft/2,006 m | North-central Blacks | Thomas "Big Tom" Wilson (1825–1909), a famous bear hunter and mountain guide |

| Mount Gibbes | 6,560 ft/1,999 m | Southern Blacks | Robert Gibbes, a surveyor |

| Clingmans Peak | 6,540 ft/1,993 m | Southern Blacks | Thomas Lanier Clingman (1812–1897), a politician and surveyor |

| Potato Hill | 6,475 ft/1,974 m | North-central Blacks | |

| Potato Knob | 6,420 ft/1,957 m | Southern Blacks | The mountain's shape, which looks like an upright potato |

| Celo Knob | 6,327 ft/1,928 m | Northern Blacks | The Cherokee word selu, meaning "corn" |

| Mount Hallback | 6,320 ft/1,926 m | North-central Blacks | |

| Blackstock Knob | 6,320 ft/1,926 m | Southern Blacks | Nehemiah Blackstock (1794–1880), a surveyor |

| Gibbs Mountain | 6,224 ft/1,897 m | Northern Blacks | A Methodist preacher who visited the area in the early 1800s |

| Winter Star Mountain | 6,212 ft/1,893 m | Northern Blacks | |

| Yeates Knob | 5,920 ft/1,804 m | Western Blacks | |

| The Pinnacle | 5,665 ft/1,727 m | Southern Blacks |

Understanding the Geology of the Black Mountains

The Black Mountains are mostly made of Precambrian gneiss and schist rocks. These rocks formed over a billion years ago from ancient sea sediments. The mountains themselves were created about 200–400 million years ago during the Alleghenian orogeny. This was a time when two huge land plates collided, pushing up what are now the Appalachian Mountains to form a large plateau. Over time, weather and smaller geological events carved out the mountains we see today.

During the last Ice Age, about 20,000–16,000 years ago, glaciers did not reach Southern Appalachia. However, the colder temperatures drastically changed the forests. A treeless tundra (a cold, treeless plain) likely covered the Black Mountains and nearby mountains above 3,500 feet (1,067 meters). Spruce-fir forests grew at lower elevations during this period. Hardwood trees moved to warmer areas in the coastal plains. As the ice sheets melted about 16,000 years ago and temperatures rose, the hardwoods returned to the river valleys and lower slopes. The spruce-fir forest then moved back to the higher elevations. Today, the spruce-fir forest on top of the Black Mountains is one of only about ten such "islands" left in the Southern Appalachian mountains.

Plants and Animals of the Black Mountains

The forests of the Black Mountains are usually divided into three zones based on how high they are. These are the spruce-fir forest, the northern hardwoods, and the Appalachian hardwoods. The Southern Appalachian spruce–fir forest, sometimes called "boreal" or "Canadian," is a special plant community. It is found only on a few high peaks in the Southern Appalachians. It is more like a high-elevation cloud forest. This forest is mostly made up of red spruce and Fraser fir trees and covers elevations above 5,500 feet (1,676 meters).

The northern hardwoods, which include beech, yellow birch, and buckeye trees, grow well between 4,500 feet (1,372 meters) and 5,500 feet (1,676 meters). The more varied Appalachian hardwoods, such as yellow poplar and different kinds of hickory, oak, and maple trees, are common on the slopes and in the stream valleys below 3,000 feet (914 meters). Pine forests, mainly with Table Mountain pine, pitch pine, and Virginia pine, are found on the drier south-facing slopes. Mountain paper birch, which is rare in North Carolina, grows in some spots on the slopes of Mount Mitchell.

The wildlife in the Black Mountains is typical for the Appalachian highlands. Mammals include black bears, white-tailed deer, raccoons, river otters, minks, bobcats, and the endangered northern flying squirrel. Bird species include the wild turkey, the northern saw-whet owl, and the pileated woodpecker. Peregrine falcons and different kinds of hawks are known to nest in the higher elevations. Brook trout, which are usually found in colder northern areas, live in the streams at the base of the Black Mountains.

A Look at the History of the Black Mountains

Native Americans have likely hunted in the Black Mountains for thousands of years. At Swannanoa Gap, just south of the range, archaeologists have found signs of people living there as far back as the Archaic period (8000–1000 BC). They also found evidence from the Woodland period (1000 BC – 1000 AD) and the Mississippian period (around 900-1600 AD). The Mississippian-period village of Joara was located near the town of Morganton to the southeast.

The Hernando de Soto expedition, which was trying to travel from the Florida coast to the Pacific Ocean, is thought to have passed through the North Toe River valley in May 1540. This means they would have been the first Europeans to see the Black Mountains. An expedition led by Juan Pardo likely crossed the Blue Ridge at Swannanoa Gap in October 1567. Both expeditions spent a lot of time at Joara.

Early Settlers and Explorers

For much of the 1700s, the Black Mountains were a hunting ground on the eastern edge of Cherokee territory. However, by 1785, the Cherokee had signed away ownership of the Black Mountains to the United States. Soon after, European-American settlers moved into the Cane and South Toe valleys. These early settlers farmed the river valleys. They sold animal furs, ginseng, tobacco, liquor, and extra crops at markets in nearby Asheville. The early farmers also brought large herds of cattle and hogs, which did well in the valleys and mountain areas.

In 1789, a French botanist named André Michaux came to America. He was sent by the King of France to collect unusual plant samples. He made his first trip into the Southern Appalachian Mountains, which included a short visit to the Blacks. Michaux returned to the Blacks in August 1794. He collected several plant samples that grow well above 4,000 feet (1,219 meters). Michaux's discoveries, published in the early 1800s, were among the first to show how many different and important plants lived in Southern Appalachia.

The Great Mountain Debate: Elisha Mitchell and Thomas Lanier Clingman

In the early 1800s, Mount Washington in New Hampshire was thought to be the highest peak in the Eastern United States. Many North Carolinians started to doubt this after Michaux's findings. In 1835, North Carolina professor Elisha Mitchell (1793–1857) was sent to the western part of the state. His job was to measure the height of Grandfather Mountain, the Roan Highlands, and the Black Mountains. Using a simple barometer, Mitchell easily measured Grandfather and Roan. However, he found it hard to figure out which of the Black Mountains was the highest.

After measuring Celo Knob, Mitchell went down to the Cane River Valley to ask for advice from the local people. Two local guides led Mitchell up a bear trail to what they believed was the highest summit. It's not clear exactly which mountain they climbed, but it was likely Mount Gibbes, Clingmans Peak, or Mount Mitchell. Mitchell measured its height at 6,476 feet (1,974 meters), which was later found to be too low. But this measurement showed that the Black Mountains were higher than Mount Washington, making them the highest in the Eastern United States.

Mitchell returned to the Black Mountains in 1838 and 1844, getting higher measurements each time. Other surveyors visited in later years, including Nehemiah Blackstock in 1845 and Arnold Guyot in 1849. By Mitchell's third trip in 1844, locals were calling what is now Clingmans Peak "Mount Mitchell." They thought this was the highest peak Mitchell had measured. In 1855, Thomas Lanier Clingman (1812–1897), a politician and former student of Mitchell's, climbed a peak north of Stepps Gap known as Black Dome (which is now Mount Mitchell). He measured its elevation at 6,941 feet (2,116 meters). Clingman reported his findings to the Smithsonian Institution. They agreed that Black Dome was higher, and it was suggested that the highest mountain in the Appalachians should be named for Clingman.

When Mitchell heard about Clingman's discovery, he claimed that the mountain he had measured in 1844 was actually Black Dome. He said locals had mistakenly named the peak to the south (the modern Clingmans Peak) after him. Clingman disagreed. The two argued in local newspapers throughout 1856, each claiming to have been the first to climb and measure the higher Black Dome. The debate became more intense because of the political situation in the 1850s. Mitchell was a Whig supporter, and Clingman had recently left the Whig party to join the pro-secession Democrats.

Zebulon Vance, a Whig politician and friend of Mitchell's, found the two guides Mitchell had used in 1844. When they described their route, it seemed Mitchell had indeed climbed Mount Gibbes. Finally, in 1857, Mitchell returned to the Black Mountains to get more accurate measurements. One evening, while trying to reach the Cane River Valley, he slipped and fell into a gorge. His body was found 11 days later by the famous mountain guide Thomas "Big Tom" Wilson.

Mitchell's death caused a lot of sadness across North Carolina. Zebulon Vance led a movement to confirm Mitchell as the first to climb the highest mountain in the Eastern United States and to have the mountain named after him. Vance convinced several mountain guides to change their earlier statements and claim they had taken Mitchell to Black Dome. Mitchell was buried on top of Black Dome on land given by former governor David Lowry Swain. Clingman continued to deny that Mitchell had measured Black Dome first, but public opinion had shifted. By 1858, Black Dome was renamed "Mitchell's High Peak." Later, Mount Mitchell was renamed "Clingmans Peak," and Mitchell's High Peak was renamed "Mount Mitchell." Clingman eventually focused on the Great Smoky Mountains to the west, claiming they were higher. Guyot's measurements in the Smokies showed Clingman was wrong, but Guyot did manage to have the highest mountain in that range, known as Smoky Dome, renamed Clingmans Dome.

Tourism and Logging in the Black Mountains

When people found out the Black Mountains were the highest in the Appalachian Range, they quickly became a popular place for tourists. By the 1850s, a lodge was built in the southern part of the range. Local people like Jesse Stepp and Tom Wilson built simple cabins on the higher mountain slopes and became successful mountain guides. The American Civil War (1861–1865) temporarily stopped the tourism boom. But by the late 1870s, the industry was back. In the 1880s, brothers K.M. and David Murchison created a large game preserve in the Cane River Valley, which Tom Wilson managed.

As forests in the north were cut down for lumber in the late 1800s, logging companies looked to the untouched forests of Southern Appalachia. Between 1908 and 1912, northern lumber companies bought the rights to cut timber in most of the Black Mountains. They started huge logging operations. In 1911, one company built a narrow-gauge railroad line connecting the Swannanoa Valley with Clingmans Peak. Other narrow-gauge lines quickly followed. Between 1909 and 1915, much of the forest on the upper slopes and crest was cut down. A higher demand for red spruce during World War I led to even more rapid deforestation of the spruce-fir forest at higher elevations. As forests were removed, forest fires (caused by dry brush left by loggers) and erosion destroyed what was left of the landscape.

Protecting the Black Mountains: The Conservation Movement

Many North Carolinians, including Governor Locke Craig and state forester John Simcox Holmes, were worried about the harmful logging practices that were destroying the Black Mountains. The North Carolina state legislature first rejected a plan to create a state park at Mount Mitchell in 1913. So, Governor Craig began talking with (and possibly threatened) the logging company Perley and Crockett to save the forest on Mount Mitchell. He and Holmes also worked to get a state park created. The state legislature finally approved buying land between Stepps Gap and the summit of what is now Big Tom in 1915. This land became the main part of Mount Mitchell State Park. The Pisgah National Forest, started in 1916, also began buying and replanting logged lands.

In 1922, the Mount Mitchell Development Company finished the first road for cars to Mount Mitchell. It connected the summit with the Swannanoa Valley. Adolphus and Ewart Wilson (the son and grandson of "Big Tom" Wilson) soon finished a road connecting the Cane River Valley with the summit of Mitchell. The state eventually closed the Wilsons' road, but allowed Ewart Wilson to run an inn at Stepps Gap until the early 1960s. NC-128, which connects Mount Mitchell with the Blue Ridge Parkway, was finished in 1948.

Environmental Challenges Facing the Black Mountains

The Black Mountains, like many other mountain ranges in the Appalachians, are currently facing threats from acid rain and air pollution. Many of the famous red spruce and Fraser fir trees are dead or dying partly because of this pollution. A bigger threat to the fir trees, however, is the balsam woolly adelgid. This insect might have an easier time killing the firs because the trees are already weakened by acid rain. In some recent studies, individual Fraser fir trees that are resistant to the adelgid have been found. This gives hope that these trees will help regrow a healthy, mature fir forest at the highest parts of the mountains.

At lower elevations in the Black Mountains, eastern and Carolina hemlock trees grow on moist slopes near streams. A recreation area on the Toe River at the base of Mount Mitchell is even called "Carolina Hemlocks" because of these trees. These hemlocks are also being attacked by an introduced pest, the hemlock woolly adelgid. This insect has only arrived in the last few years, and the health of the hemlocks in the region is quickly getting worse. Scientists are currently releasing predator beetles that will hopefully eat enough adelgids to control their population. This would allow the hemlocks to grow strong again.

The area around the Black Mountains is also seeing fast population growth. Many retirees from other states are moving into the region. Because there are not many zoning laws, this has led to quick development of cabins on ridgetops, large second homes on lower ridges, and deforestation. This threatens the natural beauty of the region. And even though many people visit the Black Mountains for their amazing scenic views, visibility has been greatly reduced because of tiny particles in the air.

Images for kids

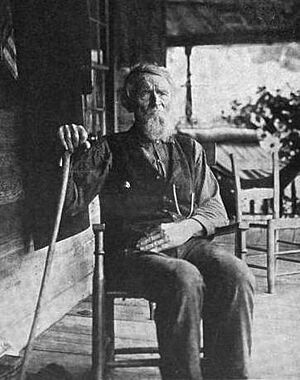

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |