Swing Around the Circle facts for kids

The Swing Around the Circle was a speaking tour by U.S. President Andrew Johnson in 1866. He traveled across the country to get support for his ideas about how to rebuild the Southern states after the Civil War. He also wanted people to vote for the politicians he supported in the upcoming elections.

The tour's name came from its route: it started in Washington, D.C., went to New York, then west to Chicago, south to St. Louis, and finally east through the Ohio River valley back to Washington.

President Johnson faced a lot of disagreement in the Northern states. Many people thought his plans for "Reconstruction" were too easy on the Southern states. They felt these states were going back to their old ways, which included treating former slaves unfairly. Johnson hoped to win over moderate Republicans by talking to them directly. However, his tour ended up making them even more upset. One of his supporters even said it would have been better if the tour had never happened. This tour later became a key part of the reasons for trying to impeach President Johnson.

Contents

Why the Tour Happened

President Johnson first wanted his Reconstruction plans to help heal the country after the war, just as President Abraham Lincoln had promised. But as Congress started making laws to protect the rights of former slaves, Johnson, who used to own slaves himself, began to act differently. He vetoed (rejected) laws that helped civil rights and pardoned many former Confederate officials. This led to harsh treatment of freed slaves in the South. Also, many former Confederate leaders and wealthy people from before the war returned to power.

These actions made the "Radical Republicans" in Congress very angry. They also slowly lost the support of moderate Republicans, who had been Johnson's allies. By 1866, Congress was so against the President that they managed to overrule a presidential veto for the first time in over twenty years. This saved a bill that helped the Freedmen's Bureau, an agency that assisted former slaves. Johnson also upset members of his own cabinet, and three of them quit in 1866.

The elections that year were seen as a test of Johnson's popularity. He had become President after Lincoln was killed, not by being elected himself. Johnson was known for being a good speaker in his earlier political campaigns. So, he decided to go on a speaking tour, which was very unusual for a sitting President. His two loyal cabinet members, Secretary of State William Seward and Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, joined him. To attract bigger crowds and show his importance, Johnson also brought along Civil War heroes like David Farragut, George Custer, and Ulysses S. Grant. Grant was the most admired person in the country at that time.

The Tour Begins

Early Days of the Tour

Over 18 days, Johnson and his group stopped in many cities. These included Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York City, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, St. Louis, Indianapolis, Louisville, Cincinnati, and Pittsburgh. They also made quick stops in smaller towns.

Because Presidents usually did not campaign like this, many people thought Johnson's tour was undignified. His advisors asked him to stick to prepared speeches. But Johnson, who often spoke from the heart, only made a rough plan and spoke freely.

At first, Johnson was welcomed with excitement, especially in Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York. At each stop, he gave a similar speech. He thanked the crowd, praised the army and navy, and said he was still the same person. He claimed his views had not changed since the war and that he still wanted to keep the states united. He often talked about how he rose from being a tailor to the presidency. He even compared himself to Jesus Christ, saying he liked to pardon people who had made mistakes. He also claimed that Congress, especially Thaddeus Stevens and the Radical Republicans, wanted to break up the Union, and he was trying to stop them.

The newspapers gave him mostly good reviews during the first part of the tour. However, when Johnson entered the Midwest, where Radical Republicans were very strong, he started to face much more unfriendly crowds. Some people came because they had heard about his earlier speeches, and others were organized by Republican leaders in those towns.

Trouble on the Tour

Johnson's stop in Cleveland on September 3 was a turning point. The crowd was large, but it included many hecklers (people who shouted insults). Many of these hecklers were put there by the Radical Republicans. They tried to make Johnson angry during his speech. When someone yelled "Hang Jeff Davis!" in Cleveland, Johnson angrily replied, "Why don't you hang Thad Stevens and Wendell Phillips?" When he left the stage, reporters heard his supporters telling him to keep his dignity. Johnson's reply, "I don't care about my dignity," was printed in newspapers everywhere. This ended the tour's good press.

After this and other angry speeches in southern Michigan, the Illinois governor, Richard J. Oglesby, refused to attend Johnson's Chicago stop on September 7. The Chicago city council also stayed away. Johnson did okay in Chicago, giving a short, pre-written speech. But his temper got the best of him again in St. Louis on September 9. A heckler provoked him, and Johnson accused Radical Republicans of causing the New Orleans Riot that summer. He again compared himself to Jesus and the Republicans to his betrayers. He also defended himself against false accusations of being a tyrant.

The next day in Indianapolis, the crowd was so hostile and loud that Johnson could not speak at all. Even after he left, fighting broke out in the streets between Johnson's supporters and opponents.

In other places like Kentucky, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, people shouted for Grant, who refused to speak. They also cheered loudly for "Three cheers for Congress!" to drown out Johnson.

A Sad Event

On September 14 in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, a temporary platform built for the President's appearance broke. Hundreds of people fell into a drained canal 20 feet below. Thirteen people died. Johnson tried to stop the train to help the injured, but it had to keep moving because of other train schedules. A few people from the presidential group stayed to help, but Johnson and the rest continued to Harrisburg. It looked like Johnson had carelessly left the scene of a terrible accident. Johnson later gave $500 (which would be about $8,318 today) to help the victims.

How People Reacted

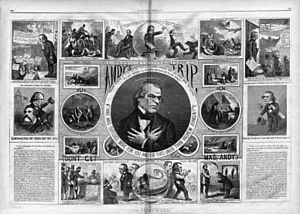

The newspapers strongly criticized Johnson for his terrible speeches and appearances. The New York Herald, which had been his biggest supporter, said it was "mortifying" (embarrassing) to see the President act so undignified. Johnson was also made fun of by two important cartoonists and humorists of that time: David Ross Locke and Thomas Nast. Nast created three famous drawings that mocked Johnson and the tour.

Johnson's Republican opponents quickly used this to their advantage. Thaddeus Stevens gave a speech calling the tour "the remarkable circus that traveled through the country." He said Johnson "entered into street brawls with common blackguards" (rude people). Charles Sumner also gave speeches, telling people to vote for Republicans. He said, "the President must be taught that usurpation and apostasy cannot prevail." This meant Johnson needed to learn that taking power unfairly and changing his beliefs would not work.

Even Johnson's supporters were unhappy with the tour. Former Georgia Governor Herschel V. Johnson wrote that the President had "sacrificed the moral power of his position." He felt it had greatly harmed the effort to rebuild the country. James Doolittle, a Senator from Wisconsin, sadly said the tour had "cost Johnson one million northern voters."

What Happened Next

When President Johnson returned to Washington, he had even less support in the North than when he started. His only remaining friends in Congress were Southern Democrats. Since most of these were former rebels, Johnson's reputation suffered even more by being linked to them. The Republican party won a huge victory in the congressional elections. The new Congress then took control of Reconstruction from the White House with the Reconstruction Acts of 1867.

Johnson openly disagreed with Congress and fought hard over national policy. However, the Republicans now had so many votes in Congress that they could keep Johnson from doing what he wanted. They even had enough votes to try to impeach Johnson. They tried unsuccessfully in 1867 and then successfully in 1868.

The impact of the Swing Around the Circle was clear even in the articles of impeachment. One of the articles accused the President of making "intemperate, inflammatory, and scandalous harangues" (angry, insulting speeches). It said he made "loud threats and bitter menaces" against Congress and the laws, while crowds cheered and laughed. This article specifically referred to speeches Johnson gave in Washington, Cleveland, and St. Louis in 1866. During the impeachment trial, reporters and others were called to testify about these speeches. However, the impeachment managers decided not to vote on this specific article because it did not have enough support.

The Republicans won the White House in 1868 and kept control until 1885. Congress remained the most powerful part of the government until the end of the 1800s. So, the Swing Around the Circle tour started a long series of political defeats that weakened Johnson, the Democratic Party, and the presidency for several years.

|

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |