Peninsula campaign facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Peninsula campaign |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

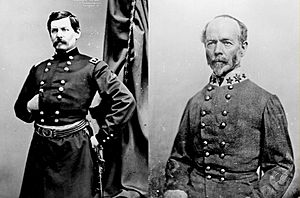

George B. McClellan and Joseph E. Johnston, leaders of the Union and Confederate armies in the Peninsula campaign |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| George B. McClellan | Joseph E. Johnston Gustavus Woodson Smith Robert E. Lee John B. Magruder |

||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Army of the Potomac | Army of Northern Virginia | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 23,119 | 29,298 | ||||||

The Peninsula campaign was a big military operation during the American Civil War. It was launched by the Union army in Virginia from March to July 1862. This was the first major attack in the eastern part of the war.

Major General George B. McClellan led the Union forces. His goal was to move around the Confederate States Army and capture Richmond, the Confederate capital. McClellan had some early success against the cautious Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston. But then, General Robert E. Lee took over and became more aggressive. This led to the Seven Days Battles, which was a big defeat for the Union.

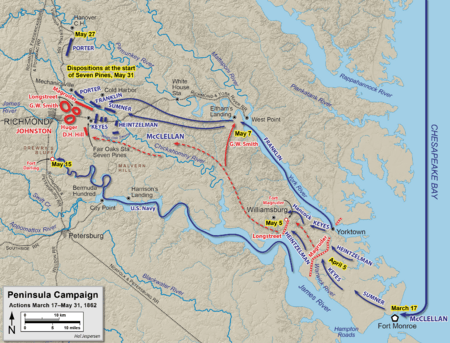

McClellan's army landed at Fort Monroe and moved towards Richmond. Confederate Brigadier General John B. Magruder had set up strong defenses, which surprised McClellan. Instead of a quick advance, McClellan had to prepare for a siege of Yorktown. Before the siege was ready, the Confederates, now led by Johnston, started to retreat towards Richmond.

The first major fight was the Battle of Williamsburg. Union troops won some small victories, but the Confederates kept retreating. An attempt by the Union Navy to reach Richmond by river was stopped at the Battle of Drewry's Bluff.

As McClellan's army got close to Richmond, a small battle happened at Hanover Court House. Then, Johnston launched a surprise attack at the Battle of Seven Pines. This battle was very costly for both sides. Johnston was wounded and replaced by Robert E. Lee. Lee then led a series of attacks known as the Seven Days Battles. In the end, the Union army could not enter Richmond.

Contents

What Was Happening Before the Campaign?

The Military Situation in 1862

In August 1861, Major General George B. McClellan created the Army of the Potomac. He was its first commander. McClellan worked hard to organize his new army. He visited his troops often, which made them feel good about their leader. He also built strong defenses around Washington, D.C. These defenses had many forts and guns.

On November 1, 1861, McClellan became the general-in-chief of all Union armies. President Abraham Lincoln worried that this was too much work for one person. But McClellan said he could handle it all.

In January 1862, McClellan shared his plan to attack Richmond. He wanted to move his army by ship to Urbanna, Virginia. This would allow him to go around the Confederate forces. On January 27, Lincoln ordered all armies to start fighting by February 22. Lincoln then ordered McClellan to attack Confederates near Manassas. McClellan disagreed and wrote a long letter explaining his Urbanna plan. Lincoln reluctantly approved it.

On March 8, Lincoln held a meeting with McClellan's officers. He wanted to know if they trusted the Urbanna plan. They mostly said yes. Lincoln then named specific officers to lead different parts of the army.

Before McClellan could start, Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston moved his forces. They left their positions near Washington. This made McClellan's Urbanna plan useless. McClellan then decided to land his troops at Fort Monroe in Virginia. From there, they would march up the Virginia Peninsula to Richmond. People criticized McClellan because Johnston's army had tricked the Union. They used fake cannons, called Quaker Guns, to make their defenses look stronger.

Another problem was the Confederate ironclad ship, CSS Virginia. This ship caused panic in Washington. It made it hard for Union ships to support McClellan on the James River. In the Battle of Hampton Roads (March 8–9, 1862), the Virginia sank Union wooden ships. The next day, the Union ironclad USS Monitor arrived. This was the first battle between two ironclad ships. The battle was a tie, but it showed that ironclad ships were the future of naval warfare.

On March 11, 1862, Lincoln removed McClellan as general-in-chief. He only commanded the Army of the Potomac. Lincoln said this would let McClellan focus on Richmond. But McClellan felt it was a trick to make his campaign fail.

Who Was Fighting?

The Union Army

| Union Corps Leaders |

|---|

|

The Army of the Potomac had about 50,000 soldiers when McClellan arrived. This number grew to 121,500 before the fighting began. The army was split into different groups called corps:

- II Corps, led by Brig. Gen. Edwin Vose Sumner.

- III Corps, led by Brig. Gen. Samuel P. Heintzelman.

- IV Corps, led by Brig. Gen. Erasmus D. Keyes.

- A division from the I Corps, led by Brig. Gen. William B. Franklin.

- Reserve infantry led by Brig. Gen. George Sykes.

- Cavalry led by Brig. Gen. George Stoneman.

- The Fort Monroe soldiers, 12,000 men under Maj. Gen. John E. Wool.

The Confederate Army

| Confederate Wing Leaders |

|---|

|

General Johnston's army was called the Army of Northern Virginia starting March 14. It was organized into three main parts:

- Left Wing, led by Maj. Gen. D. H. Hill.

- Center Wing, led by Maj. Gen. James Longstreet.

- Right Wing, led by Maj. Gen. John B. Magruder.

- A reserve force led by Maj. Gen. Gustavus Woodson Smith.

- Cavalry led by Brig. Gen. J. E. B. Stuart.

When the Union army arrived, only Magruder's 11,000 men were on the Peninsula. Most of Johnston's army was elsewhere. General Robert E. Lee became a chief military adviser to Confederate President Jefferson Davis on March 13.

Confederate forces in the Shenandoah Valley also played a role. About 50,000 Union soldiers were chasing a smaller force led by Stonewall Jackson. Jackson's clever moves kept these Union soldiers from joining McClellan. This made McClellan very upset, as he had planned for them to help him.

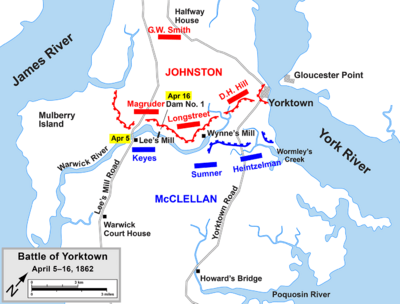

Magruder had set up three lines of defense across the Peninsula. The most important was the Warwick Line. It used the Warwick River as a natural barrier. By building dams, they made the river a big obstacle.

The Start of the Campaign

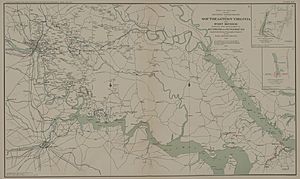

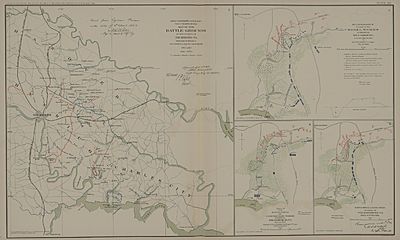

Moving to the Peninsula and the Yorktown Siege

McClellan's army started sailing from Alexandria on March 17. It was a huge fleet of ships. They carried 121,500 men, many cannons, wagons, and horses. One observer called it the "stride of a giant."

Since the Confederate ironclad Virginia was still active, the U.S. Navy couldn't promise to protect McClellan's ships on the rivers. So, McClellan decided to advance up the Peninsula by land, starting on April 4.

On April 5, Union troops met Confederate defenses at Lee's Mill. McClellan thought they would pass easily. But Magruder used a clever trick. He made one company of soldiers march in circles. This made it look like endless reinforcements were arriving. He also spread his cannons far apart and fired them randomly. This convinced the Union soldiers that the defenses were very strong. They reported that 100,000 Confederates were in their way.

McClellan decided not to attack. Instead, he ordered his army to dig trenches and prepare for a siege of Yorktown. Meanwhile, General Johnston sent more soldiers to Magruder.

McClellan was also told that the I Corps would not join him. This corps was kept to defend Washington, D.C. McClellan protested, saying he needed all his promised troops. But he moved forward anyway. For the next 10 days, McClellan's men dug while Magruder received more soldiers. By mid-April, Magruder had 35,000 men.

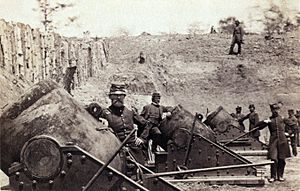

McClellan believed his cannons were better than the enemy's. His siege preparations at Yorktown included 15 batteries with over 70 heavy guns. These guns could fire a lot of weight at the enemy.

On April 16, Union forces tested a weak spot in the Confederate line at Dam No. 1. Magruder knew his position was weak and ordered it strengthened. Union General William F. "Baldy" Smith was ordered to stop the Confederates from building more defenses.

Four companies of the 3rd Vermont Infantry crossed the dam and pushed back the defenders. But Confederate soldiers under Brig. Gen. Howell Cobb counterattacked. The Vermont soldiers had to retreat, suffering losses. Later, other Union attacks also failed.

For the rest of April, the Confederates, now 57,000 strong and led by Johnston, improved their defenses. McClellan slowly brought up his huge siege cannons. He planned to fire them on May 5. Johnston knew his army couldn't survive such a bombardment. So, on May 3, he started sending his supply wagons towards Richmond. Escaped slaves told McClellan this, but he didn't believe them. He thought an army of 120,000 would stay and fight.

On the evening of May 3, the Confederates fired their cannons briefly, then went silent. Early the next morning, a Union officer went up in an observation balloon. He saw that the Confederate defenses were empty.

McClellan was shocked. He sent cavalry to chase Johnston. He also ordered a division of soldiers to go by ship up the York River. The goal was to cut off Johnston's retreat.

Key Battles of the Campaign

Battle of Williamsburg

By May 5, Johnston's army was moving slowly on muddy roads. Union cavalry was fighting with Confederate cavalry, who were protecting Johnston's retreat. To buy time, Johnston left some of his forces at Fort Magruder. This fort was near Williamsburg. The Battle of Williamsburg was the first big battle of the campaign. About 41,000 Union and 32,000 Confederate soldiers fought.

Union General Joseph Hooker's division led the attack. They assaulted Fort Magruder but were pushed back. Confederate counterattacks, led by Maj. Gen. James Longstreet, almost overwhelmed Hooker's men. Hooker had been fighting alone for hours, waiting for help.

Confederate soldiers left their defenses and attacked Hooker. Union General Philip Kearny's division arrived around 2:30 p.m. Kearny bravely rode his horse in front of his lines. He urged his men forward, pushing the Confederates back. Intense fighting continued until late afternoon.

Union General Winfield Scott Hancock's brigade attacked Longstreet's left side. Maj. Gen. D. H. Hill ordered a counterattack. But Hancock's 3,400 soldiers and eight cannons were much stronger. Hill called off the attack, but Hancock ordered his own counterattack. This attack was later called a "superb" bayonet charge.

Confederate losses at Williamsburg were 1,682, while Union losses were 2,283. McClellan called it a "brilliant victory." But for the Confederates, it was a success because it delayed the Union army. This allowed most of their army to continue retreating towards Richmond.

Battle of Eltham's Landing

McClellan wanted to use ships to get around Johnston's army. It took two days to load soldiers and equipment onto the ships. So, this force could not help at Williamsburg. Their destination was Eltham's Landing on the Pamunkey River. This spot was near a key road used by Johnston's retreating army.

Union soldiers landed in small boats and built a floating dock. They worked all night. The only resistance was a few shots from Confederate pickets.

Johnston ordered Maj. Gen. G. W. Smith to protect the road. Smith sent two brigades to do this. On May 7, Union General John Newton's brigade was pushed back by Confederate troops. The Union soldiers retreated to an open area near the landing. They sought cover from Union gunboats.

The Confederates fired cannons at the gunboats, but their guns couldn't reach. They pulled back around 2 p.m. Union troops moved back into the woods. This battle was a draw. But Franklin missed a chance to stop the Confederate retreat from Williamsburg.

Norfolk and Drewry's Bluff

President Lincoln visited Fort Monroe on May 6. He believed the city of Norfolk was weak and that the James River could be controlled. McClellan was too busy to meet with the president. Lincoln, using his power as commander in chief, ordered naval attacks on Confederate defenses. Union troops occupied Norfolk on May 10 with little fighting.

After Norfolk was taken, the CSS Virginia had no home port. Its captain decided to sink the ship on May 11. This prevented the Union from capturing it. This opened the James River to Union gunboats.

The only thing protecting Richmond from a river attack was Fort Darling. This fort was on Drewry's Bluff, overlooking a sharp bend in the river. It was about 7 miles from Richmond. Confederate defenders included marines, sailors, and soldiers. The fort had eight cannons. An underwater barrier of sunken ships and debris also blocked the river.

On May 15, Union Navy ships sailed up the James River to test Richmond's defenses. The USS Galena got close to the fort. But before it could fire, two Confederate shots hit it. The battle lasted over three hours. The Galena was hit 45 times. The USS Monitor was also hit but its strong armor protected it. Around 11 a.m., the Union ships pulled back.

The strong fort at Drewry's Bluff stopped the Union advance. It was only 7 miles from the Confederate capital. The Navy reported that troops could be landed closer to Richmond. But the Union Army never used this information.

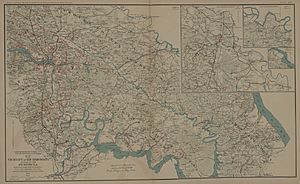

Armies Meet Near Richmond

Johnston pulled his 60,000 men back into Richmond's defenses. Their defense line started at the James River. It stretched behind the Chickahominy River. This river was a natural barrier, turning the plains into swamps in spring. Johnston's men burned most of the bridges over the Chickahominy. They set up strong defenses north and east of the city.

McClellan positioned his 105,000-man army to focus on the northeast. He wanted to use the Pamunkey River for supplies. He also expected more troops to arrive from Fredericksburg.

The Army of the Potomac moved slowly. They set up supply bases along the Pamunkey River. White House Landing became McClellan's main base. He used the railroad to bring his heavy cannons close to Richmond. McClellan moved slowly because he thought the Confederates had many more soldiers than he did. By the end of May, the army had built bridges over the Chickahominy. They faced Richmond, with one-third of the army south of the river and two-thirds north. This setup made it hard for one part of the army to help the other quickly.

| New Union Corps Leaders |

|---|

|

On May 18, McClellan reorganized his army. He promoted Fitz John Porter to lead the new V Corps. William B. Franklin was promoted to lead the VI Corps. The Union army had 105,000 men. Johnston had 60,000. But McClellan's spies gave him wrong information. He believed he was outnumbered two to one. There were many small fights between the armies from May 23 to May 26. People in Richmond were very worried.

Battle of Hanover Court House

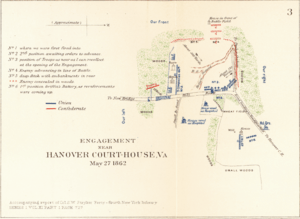

McClellan heard a rumor that 17,000 Confederate soldiers were moving to Hanover Court House. This was north of Mechanicsville. If true, it would threaten his army's right side. It would also make it hard for reinforcements to arrive. Union cavalry found that the enemy force was only 6,000. But McClellan was still worried. He ordered Porter and his V Corps to deal with the threat.

Porter set out on May 27 with about 12,000 men. The Confederate force was actually about 4,000 men. They were led by Col. Lawrence O'Bryan Branch. They were guarding the railroad.

Porter's men approached in heavy rain. Around noon, they fought with the Confederates. Porter's main force arrived and pushed the Confederates back. Porter chased them with most of his men. He left three regiments to guard a key intersection. This left the back of Porter's command open to attack.

Branch also made a mistake. He thought Porter's force was much smaller. He attacked. The first attack was pushed back. But Branch's men eventually almost destroyed the Union force. Porter quickly sent more regiments to help. The Confederate line broke and they retreated.

Union losses at Hanover Court House were between 355 and 397. The Confederates lost 200 killed and 730 captured. McClellan called it another "glorious victory." But it was a messy fight where the larger Union army won. The Union army's right side was safe. But the reinforcements McClellan expected never came. This was because Union forces were defeated in the First Battle of Winchester.

This battle also affected McClellan's readiness for the next big fight. While Porter was away, McClellan didn't want to move more troops south of the Chickahominy. This made his left side an easier target for Johnston. McClellan was also sick with malaria.

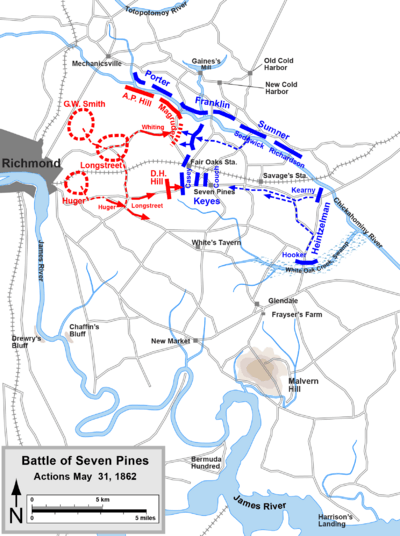

Battle of Seven Pines

Johnston knew he couldn't survive a long siege of Richmond. So, he decided to attack McClellan. His first plan was to attack the Union right side, north of the Chickahominy River. But then he learned that Union reinforcements would not arrive. So, he decided to attack the two Union corps south of the river. This would leave them cut off from the rest of the Union army.

Johnston planned to use two-thirds of his army (about 51,000 men) against 33,000 Union soldiers. The plan was complicated. It called for some Confederate divisions to distract Union forces north of the river. Meanwhile, Longstreet would lead the main attack from three directions. The Union division farthest forward was led by Brig. Gen. Silas Casey. His 6,000 men were the least experienced. If Casey's men could be defeated, the other Union corps could be trapped against the river.

The plan went wrong from the start. Johnston's orders were unclear. Longstreet either misunderstood his orders or changed them. This delayed the attack and limited it to a small area. A big thunderstorm on May 30 made things worse. It flooded the river, destroyed most Union bridges, and turned roads into mud.

The attack began badly on May 31. Longstreet marched the wrong way. Other Confederate generals were delayed. Johnston and his second-in-command waited for news of the battle. Five hours after it was supposed to start, at 1 p.m., D.H. Hill attacked Casey's division.

Casey's line struggled, but his men fought hard. They suffered many losses. The Confederates only used a small part of their forces. Casey asked for help, but it was slow to arrive. Eventually, the Confederates broke through. Casey's men retreated to a second line of defense.

Hill, now with more soldiers from Longstreet, attacked the second Union line around 4:40 p.m. Hill tried to attack the Union right side, which caused the Union line to collapse. Johnston went forward with three brigades and met strong resistance. Soon, many Union reinforcements arrived. Union General Edwin Vose Sumner heard the battle from north of the river. He sent a division across the only remaining bridge. The bridge was about to collapse, but the weight of the soldiers helped hold it steady. After they crossed, the bridge was swept away. These Union soldiers helped stop the Confederate attack.

At dusk, Johnston was wounded and taken to Richmond. G.W. Smith took temporary command. Smith was unsure what to do next. President Davis and General Lee were not impressed. After the fighting ended the next day, Davis replaced Smith with Lee. Lee became the new commander of the Army of Northern Virginia.

On June 1, the Confederates attacked again. But the Union had more reinforcements and strong positions. The fighting ended around 11:30 a.m. when the Confederates pulled back. McClellan arrived on the battlefield, but the Union army did not counterattack.

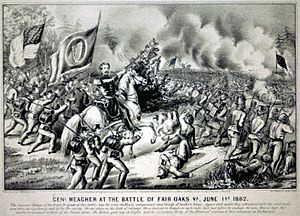

Both sides claimed victory. Union losses were 5,031. Confederate losses were 6,134. McClellan's advance on Richmond was stopped. The Army of Northern Virginia fell back into Richmond's defenses. Union soldiers often called it the Battle of Fair Oaks Station. Confederates called it Seven Pines.

The Seven Days Battles

Even though he claimed victory at Seven Pines, McClellan was shaken. He moved almost all his army south of the river. He still planned to capture Richmond, but he lost his advantage. He never got it back.

Lee used the month-long pause to strengthen Richmond's defenses. He extended them south to the James River. The new defense line was about 30 miles long. To gain time, Lee made his small army seem bigger. McClellan was also worried by J. E. B. Stuart's bold cavalry ride. Stuart rode all around the Union army, gathering information and causing trouble.

The second part of the Peninsula campaign went badly for the Union. Lee launched strong attacks east of Richmond in the Seven Days Battles (June 25–July 1, 1862). None of these battles were big Confederate victories. The Battle of Malvern Hill on the last day was a big Confederate defeat. But Lee's fierce attacks and the sudden arrival of Stonewall Jackson's fast-moving soldiers scared McClellan. He pulled his forces back to a base on the James River.

Lincoln later ordered the army to return to Washington, D.C. They were needed to support another Union army. The Virginia Peninsula was quiet until May 1864.

What Happened Next?

See also

In Spanish: Campaña de la Península para niños

In Spanish: Campaña de la Península para niños