USS Monitor facts for kids

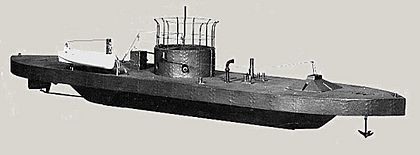

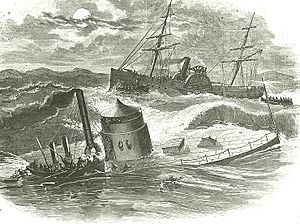

Drawing of USS Monitor at sea

|

|

Quick facts for kids History |

|

|---|---|

| Name | Monitor |

| Ordered | 4 October 1861 |

| Builder | Continental Iron Works, Greenpoint, Brooklyn |

| Cost | $275,000 |

| Laid down | 25 October 1861 |

| Launched | 30 January 1862 |

| Commissioned | 25 February 1862 |

| Fate | Lost at sea during a storm, 31 December 1862 (off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina) |

| Status | Wreck located 27 August 1973, partially salvaged |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Monitor |

| Displacement | 987 long tons (1,003 t) |

| Tons burthen | 776 tons (bm) |

| Length | 179 ft (54.6 m) |

| Beam | 41 ft 6 in (12.6 m) |

| Draft | 10 ft 6 in (3.2 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 6 knots (11 km/h; 6.9 mph) |

| Complement | 49 officers and enlisted men |

| Armament | 2 × 11-inch (280 mm) smoothbore Dahlgren guns |

| Armor |

|

|

USS Monitor

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Nearest city | Cape Hatteras, North Carolina |

| Area | 9.9 acres (4.0 ha) |

| Built | 1861–1862 |

| Architect | John Ericsson |

| Architectural style | Ironclad warship |

| NRHP reference No. | 74002299 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | 11 October 1974 |

| Designated NHL | 23 June 1986 |

The USS Monitor was a special warship built for the Union Navy during the American Civil War. It was the first ship of its kind to be used by the Navy. The Monitor became famous for its part in the Battle of Hampton Roads on March 9, 1862. In this battle, it fought against the Confederate ironclad ship, the CSS Virginia. The Monitor had a unique design with a revolving turret, which was a new invention at the time. This design was so successful that it led to a whole new type of armored warship called "monitors."

The ship's main designer was John Ericsson, an engineer from Sweden. It was built very quickly in just 101 days in Brooklyn, New York. The Monitor was a completely new idea in ship design. It used many new inventions that amazed the world. The Union Navy built the Monitor because they heard the Confederates were building their own armored ship, the Virginia. This Confederate ship was a big threat to Union ships blocking the harbors.

Before the Monitor arrived, the Virginia had already destroyed two Union ships. It had also run another ship aground. But when the Monitor arrived, it stopped the Virginia from causing more damage. The two ironclads fought for four hours. Neither ship could destroy the other. This battle was the first time armored warships fought each other. It changed naval warfare forever.

Later, the Confederates had to sink the Virginia when they left Norfolk in May 1862. The Monitor then went up the James River to help the Union Army. It took part in the Battle of Drewry's Bluff. In December, the Monitor was ordered to join other Union ships off North Carolina. But on its way, it sank during a storm near Cape Hatteras on the last day of 1862. The Monitor's wreck was found in 1973. Some of its parts, like its guns and turret, have been brought up. You can see them at the Mariners' Museum in Newport News, Virginia.

Contents

Building a New Kind of Ship

For a long time, ships were made of wood. But new powerful cannons could fire explosive shells. These shells could easily damage wooden ships. So, people started thinking about protecting ships with iron. This was not possible until steam engines became strong enough to carry the heavy iron.

In the 1840s, guns became so strong that no amount of wood could stop their shells. France was the first country to use armored ships. They also had the first shell guns. During the Crimean War (1854–1855), French ironclad ships showed they could take many hits without much damage. This proved that armored ships were very strong.

The Union Navy quickly changed its mind about ironclads. They heard that the Confederates were turning a captured ship, the USS Merrimack, into an ironclad. This ship was being rebuilt in Norfolk, Virginia. The Union Navy became very worried about what this Confederate ironclad, renamed Virginia, could do. They feared it could attack Union ships and even coastal cities. Newspapers in the North wrote daily about the Virginia's progress. This made the Union Navy rush to finish the Monitor.

A freed slave named Mary Louvestre brought important news to the North. She worked for a Confederate engineer on the Merrimack. In February 1862, she bravely crossed Confederate lines. She carried a secret message warning that the Virginia was almost ready. She met with Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles. He was surprised by her news. Her information made him speed up the building of the Monitor.

Getting Approval for the Monitor

After hearing about the Virginia, the U.S. Congress decided to build armored steamships. They set aside $1.5 million for this on August 3, 1861. They also created a special board to look at different designs for armored ships. The Union Navy asked for ideas for "iron-clad steam vessels of war."

John Ericsson, the Monitor's designer, didn't send in a plan at first. But he got involved when a friend, Cornelius Bushnell, needed help. Bushnell had a design for an armored ship, but the board needed a guarantee that it would float. Bushnell asked Ericsson for advice.

Ericsson then showed Bushnell a model of his own design, the future Monitor. It was based on an idea he had in 1854. Bushnell showed this model to Secretary Welles, who then told him to show it to the board. The board was unsure about Ericsson's unusual design. They worried it wouldn't float, especially in rough seas. But President Lincoln liked the design and supported it. Ericsson promised the board his ship would float, saying, "The sea shall ride over her and she shall live in it like a duck."

On September 15, the board accepted Ericsson's plan. They looked at 17 different designs. But they only recommended three, including Ericsson's Monitor. The Monitor was the most new and different design. It had a very low deck, a shallow iron hull, and relied completely on steam power. The riskiest part was its spinning gun turret, which no navy had ever used before. Ericsson promised to deliver the ship in 100 days. This promise helped convince the board to choose his design.

How the Monitor Was Designed

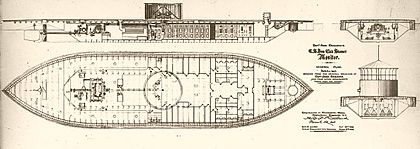

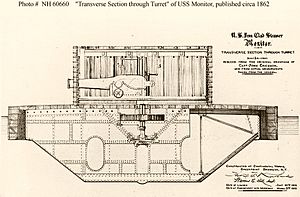

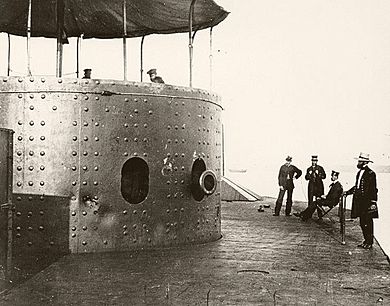

The Monitor was a very unusual ship. People sometimes joked about it, calling it "Ericsson's folly" or a "cheesebox on a raft." Its most noticeable feature was a large, round gun turret in the middle of the ship. This turret sat on a low, flat deck. The deck stuck out far past the sides of the ship's lower hull.

A small armored pilot house was at the front of the upper deck. But its position meant the Monitor couldn't shoot its guns straight forward. Ericsson wanted the ship to be a very small target for enemy fire. The ship was about 179 feet (54.6 m) long. It was 41 feet 6 inches (12.6 m) wide and had a maximum depth of 10 feet 6 inches (3.2 m) in the water. The Monitor had a crew of 49 officers and sailors.

The ship was powered by a single steam engine, also designed by Ericsson. This engine turned a 9-foot (2.7 m) propeller. The engine used steam from two boilers. It was designed to make the ship go 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph), but it was usually slower. The ship carried 100 long tons (100 t) of coal for fuel. Fans helped move air through the ship and to the boilers. If these fans stopped, the engine room could get very hot and dangerous.

The Monitor's turret was 20 ft (6.1 m) across and 9 ft (2.7 m) tall. It had 8 inches (20 cm) of armor. This made the ship a bit top-heavy. Its round shape helped cannonballs bounce off. Small steam engines turned the turret. It could make a full turn in about 22.5 seconds. But it was hard to stop the turret exactly where they wanted it. The only way to see out was through the gun ports. When the guns were not firing, heavy iron covers would close these ports. The turret weighed about 160 long tons (163 t). It rested on a central iron pole.

The turret was supposed to have two 15-inch (380 mm) guns. But they weren't ready in time. So, two 11-inch (280 mm) Dahlgren guns were used instead. Each gun weighed about 16,000 pounds (7,300 kg). They could fire a 136-pound (61.7 kg) cannonball up to 3,650 yards (3,340 m).

The armored deck was only about 18 inches (460 mm) above the water. It had two layers of 1⁄2-inch (13 mm) iron armor. The sides of the "raft" part had three to five layers of 1-inch (25 mm) iron plates. These were backed by about 30 inches (762 mm) of wood.

After the battle, some Navy officers worried that the Monitor could be easily boarded by enemies. There were ideas to use hot water or steam to stop attackers. But the chance to use such a plan never happened.

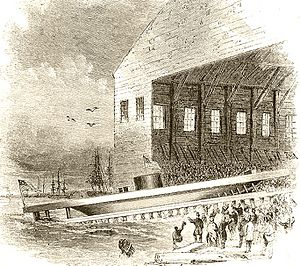

Building and Launching the Monitor

On September 21, 1861, Ericsson's design was officially accepted. Ericsson and his partners signed a contract to build the ship. There was a delay because the Navy wanted the builders to refund all the money if the Monitor wasn't a "complete success." The builders finally agreed, and the contract was signed on October 4 for $275,000.

Work began quickly. The hull was built by the Continental Iron Works in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. The turret was built in Manhattan, then taken apart and shipped to Greenpoint to be put back together. The ship's engines were also built in Manhattan.

Building the ship had some small delays, but it was mostly on track. The 100 days for construction passed on January 12, but the Navy didn't punish the builders. Ericsson named the ship "Monitor," meaning "one who warns and corrects wrongdoers." The name was approved on January 20, 1862. The Monitor was launched on January 30, 1862, to cheers from the crowd. It was officially ready for service on February 25.

Before it was fully ready, the Monitor had some test runs. On February 19, it had engine problems and had to be towed. These issues were fixed. On February 27, the ship tried to leave New York but was hard to steer. The steering gear was fixed, and new tests on March 4 were successful. Gunnery tests were also done, but there were some close calls because the recoil mechanism for the guns was not understood at first.

Ericsson's turret was a new idea for mounting guns on ships. It was soon used on naval ships around the world. The Monitor had over forty new inventions. It was very different from any other warship. Because it was built so fast and put into service quickly, some problems were found during its first trip and battle. But the Monitor still managed to fight the Virginia and protect the Union fleet.

Ericsson gave all his patent rights for the Monitor to the U.S. government. He said it was his "contribution to the glorious Union cause."

The Crew of the Monitor

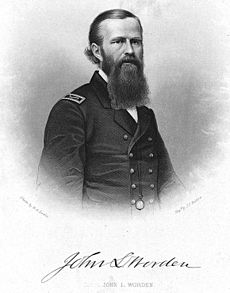

The Monitor's crew were all volunteers. There were 49 officers and sailors. The ship needed ten officers, including a commander, engineers, a doctor, and others. John Lorimer Worden was the commanding officer.

Here are some of the officers when the Monitor was first ready for service:

| Lieutenant John Lorimer Worden, Commanding Officer | |

| Lieutenant Samuel Greene, Executive Officer | Third Assistant Engineer, Robinson W. Hands |

| Acting Master, Louis N. Stodder | Fourth Assistant Engineer, Mark T. Sunstrom |

| Acting Master, J.N. Webber | Acting Assistant Paymaster, William F. Keeler |

| First Assistant Engineer, Isaac Newton Jr. | Acting Assistant Surgeon, Daniel C. Logue |

| Second Assistant Engineer, Albert B. Campbell | |

Four officers were in charge of handling the ship and its guns. The engineers managed the ship's machinery. In the turret, Lieutenant Greene and Acting Master Stodder oversaw the loading and firing of the two 11-inch guns. Each gun needed eight men to operate it.

The senior officers had eight comfortable cabins. Each had a small table, chair, and lamp. The entire crew slept on goat-skin mats. Small skylights in the deck provided light. During battle, these were covered with iron plates. The officers' dining room was well-furnished. Ericsson himself paid for the officers' furniture.

We know a lot about the Monitor's history and daily life from letters written by the crew. George Spencer Geer sent over 80 letters to his wife, Martha. These "Monitor Chronicles" give many details about the ship's short life. The letters of Paymaster William Frederick Keeler also tell a lot about life on board. These letters are kept at the Mariners' Museum. Some crew members, like Louis N. Stodder, were interviewed later in life. Stodder was one of the last to leave the Monitor before it sank.

The Monitor's Journey and Battle

On March 6, 1862, the Monitor left New York. It was towed by the tugboat Seth Low. The ship faced rough seas. Water poured into the ship through leaks and vents. The fans that helped the engines stopped working. This made the air in the engine room dangerous. Many crew members became sick. First Assistant Engineer Isaac Newton ordered the engine room cleared. He and another engineer worked hard to get the fans going again.

Later that night, the steering ropes jammed. It was very hard to control the ship. The Monitor was in danger of sinking. Commander Worden signaled for help. The tugboat towed the Monitor to calmer waters. The ship finally reached Hampton Roads at 9:00 pm on March 8. This was after the first day of the big battle had already ended.

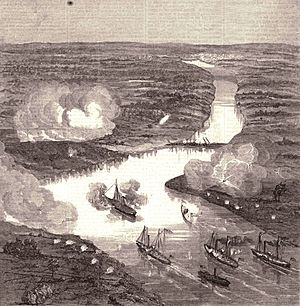

The Battle of Hampton Roads

On March 8, 1862, the Confederate ironclad Virginia attacked Union ships. The Virginia was built from the captured ship Merrimack. It destroyed two Union wooden ships. Another Union ship, the USS Minnesota, ran aground. The Virginia couldn't finish off the Minnesota before nightfall.

News of the battle quickly reached Washington. Many people worried that the Virginia would attack cities like New York or Washington. President Lincoln and his advisors were very concerned. They asked if the Monitor could stop the Virginia. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton was especially worried. He was upset that the Monitor only had two guns. But Admiral Dahlgren and other officers tried to reassure him. Lincoln was finally convinced that the Monitor could handle the challenge.

Around 9:00 pm, the Monitor arrived at Hampton Roads. Commander Worden was ordered to protect the grounded Minnesota. Under the cover of darkness, the Monitor quietly positioned itself behind the Minnesota. It waited for the morning.

The Ironclads Fight

The next morning, around 6:00 am, the Virginia set out to finish off the Minnesota. But heavy fog delayed them. In the Monitor, Commander Worden was in the pilot house. Lieutenant Greene was in command of the turret. A pilot who knew the area helped steer the ship. Communication between the pilot house and the turret was difficult. Messages had to be relayed by hand.

As the Virginia approached, it started firing at the Minnesota. But then, to the surprise of the Virginias crew, the Monitor appeared. It moved between the Virginia and the Minnesota. This stopped the Confederate ship from attacking the wooden Minnesota up close. At 8:45 am, Worden gave the order to fire. Greene fired the first shots. They bounced harmlessly off the Virginias armor.

The ironclads fought for about four hours, ending at 12:15 pm. They were usually very close to each other. Both ships moved in circles. The Virginia was slow and hard to turn because of its size.

During the battle, the Monitor's turret had problems. It was hard to turn and stop it exactly. So, the crew just let it spin and fired their guns as they passed the Virginia. The turret was hit many times. Some bolts broke off inside, making loud noises and stunning the crew. But neither ship could sink or seriously damage the other. At one point, the Virginia tried to ram the Monitor. It only grazed the Monitor and caused no damage.

The Monitor's guns might not have done much damage because they were using reduced charges. This was on advice from the gun's designer, who wasn't sure how much charge was needed to break iron plates.

The two ships collided five times. Around 11:00 am, the Monitor ran out of cannonballs in the turret. One of its gun port covers was jammed. It pulled away to shallow water to get more ammunition and fix the cover. The Virginia then turned its attention back to the Minnesota. It fired shots that set the wooden ship on fire.

When the Monitors turret was reloaded, Worden returned to the battle. But only one gun could fire. Near the end of the fight, a shot from the Virginia hit the Monitors pilot house. It cracked the iron structure where Worden was looking out. Worden cried out, "My eyes—I am blind!" He was temporarily blinded by fragments and gunpowder. Thinking the pilot house was badly damaged, Worden ordered the ship to move to shallow water. The Monitor drifted for about twenty minutes. Command passed to Lieutenant Samuel Greene. He soon ordered the Monitor back to the battle.

Shortly after the Monitor pulled back, the Virginia ran aground. Its crew was low on powder. The Virginia soon broke free and headed back to Norfolk for repairs. It thought the Monitor had left the battle. Greene did not chase the Virginia. He was ordered to stay and protect the Minnesota.

The Monitor was hit 22 times, including nine hits to its turret and two to its pilot house. It fired 41 shots. The Virginia had 97 dents in its armor. Neither ship was seriously damaged. The battle was mostly a draw. But the Monitor successfully defended the Minnesota and the Union fleet. The Virginia could not finish its destruction. This battle changed naval warfare forever. It led to many more ironclads being built.

After the Battle

After the battle, people cheered the Monitor crew. Assistant Secretary Fox, who saw the battle, came aboard. He joked, "Well gentlemen, you don't look as though you just went through one of the greatest naval conflicts on record." Commander Worden, who was blinded, was taken off the ship. He was treated at Fort Monroe and then in Washington.

The pilot house was repaired and angled to deflect shots better. Mrs. Worden visited the crew and told them her husband was recovering. She said President Lincoln had visited him. Worden later returned to naval service.

The Confederates also celebrated. Crowds cheered the Virginia as it returned. The Confederate government promoted its commander to Admiral.

Both sides tried to find ways to defeat the other's ironclad. The Union Navy even prepared a large ship, the USS Vanderbilt, to ram the Virginia.

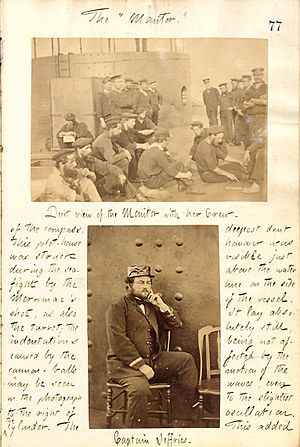

picture of the USS Monitor crew; [Bottom Picture] Lieutenant Jeffers, second commander of the USS Monitor four months after the fight at Hampton Roads in 1862]]

On April 11, the Virginia came out again. It tried to lure the Monitor into a fight. The Monitor stayed near Fort Monroe, ready to fight if attacked. The Virginia did not come closer. The Confederates also captured three merchant ships to try and provoke the Monitor. But neither side got the fight they wanted.

On May 8, the Virginia came out again while the Monitor and other Union ships attacked Confederate forts. The Union ships pulled back, hoping to lure the Virginia. But it did not follow. When Confederate forces left Norfolk on May 11, 1862, they had to destroy the Virginia.

The Battle of Drewry's Bluff

After the Virginia was gone, the Monitor was free to help the Union Army. It joined a group of ships going up the James River. Their goal was to reach Richmond, the Confederate capital. They wanted to bombard the city if possible.

The ships faced strong Confederate forts at Drewry's Bluff. These forts were high on a hill overlooking the river. The river was also blocked by sunken ships. The Monitor could not raise its guns enough to hit the forts from close range. So, it had to fire from farther away. The other Union ships were also unable to break through the defenses.

After a four-hour battle, the Union ships had to turn back. They could not get past the forts. No Union ship reached Richmond until near the end of the war.

The Monitor stayed on the James River for a while, supporting the army. But it was a long, hot summer with little action. Many crew members got sick. Officers were replaced. By the end of August, the Monitor was ordered back to Hampton Roads. Its new job was to block the James River from any new Confederate ironclads.

Repairs and Upgrades

In September, Captain John P. Bankhead took command of the Monitor. Soon after, the ship's engines and boilers needed a complete overhaul. On September 30, the Monitor was sent to the Washington Navy Yard for repairs.

When it arrived in Washington, thousands of cheering people came to see the ship that "saved the nation." The Monitor became a popular tourist attraction. People were allowed to tour the ship. Many took small parts as souvenirs.

Before the Monitor went into dry dock, President Lincoln and other officials visited. They honored the crew and former commander Worden. Worden, still recovering from his injuries, gave a speech. He talked about the ship's journey and the battle. He thanked Ericsson, Lincoln, and everyone who made the Monitor possible.

While the Monitor was being repaired, its crew was given leave. For about six weeks, the ship was in dry dock. Its bottom was cleaned. The engines and boilers were fixed. The whole ship was cleaned and painted. Some improvements were made. An iron shield was added around the top of the turret. A tall smokestack and fresh air vents were installed to make the ship better for sea travel. The living area below deck was also made larger. The two Dahlgren guns were engraved with "MONITOR & MERRIMAC – WORDEN" and "MONITOR & MERRIMAC – ERICSSON." Additional iron plates were added to cover dents from battles. Stanchions (posts) were put around the deck with ropes to make it safer in rough seas. The Monitor was ready for service again by November.

The Final Voyage

On December 24, 1862, the Monitor was ordered to go to Beaufort, North Carolina. It was to join other ships for an expedition. Some crew members who had been on the first rough trip were not happy about going to sea again.

The crew celebrated Christmas on board. The ship's cook made a special meal. The Monitor was made ready for sea, but bad weather delayed its departure until December 29.

The Monitor's design was good for river battles. But its low deck and heavy turret made it unsafe in rough ocean waters. On December 31, under the command of John P. Bankhead, the Monitor set sail. It was being towed by the steamship USS Rhode Island. A heavy storm began off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina.

The Monitor was soon in trouble. Huge waves crashed over the deck and pilot house. Water flooded into the vents and ports. The ship rolled wildly. Leaks appeared everywhere. The pumps could not keep up with the rising water. Bankhead signaled the Rhode Island for help. He raised a red lantern as a distress signal.

Bankhead ordered the anchor dropped, but it didn't help much. He then ordered the towline cut. Three crewmates volunteered to cut the thick towline. Two were swept overboard and drowned. Louis N. Stodder managed to cut the line. At 11:30 pm, Bankhead ordered all steam to the large pump. But it couldn't stop the water. After all the steam pumps failed, the crew tried hand pumps and a bucket brigade, but it was no use.

Greene and Stodder were among the last to leave the ship. Bankhead was the very last. After a frantic rescue effort, the Monitor finally sank about 16 miles (26 km) southeast of Cape Hatteras. Sixteen men were lost, including four officers. Forty-seven men were rescued by the Rhode Island's lifeboats. Bankhead, Greene, and Stodder survived, but suffered from the cold sea.

Later, there was a disagreement about why the Monitor sank. Ericsson blamed the crew. But Stodder strongly defended the crew. He said there were many unavoidable problems that caused the ship to sink. He pointed out that the ship's design itself had weaknesses in rough seas.

Finding the Monitor Again

The Navy searched for the Monitor's wreck in 1949. They found a large object in 310 feet (94.5 m) of water. But strong currents stopped divers from checking it. In 1951, a retired admiral suggested using pontoons to raise the wreck.

Interest in finding the ship grew in the early 1970s. In August 1973, a team from Duke University used sonar to search. On August 27, the Monitor was found, 111 years after it sank. It was near Cape Hatteras. They sent a camera down, but the pictures were blurry. On a second try, the camera got stuck and was lost. The sonar images didn't look like they expected. They realized the ship had flipped over when it sank. The team announced their discovery on March 8, 1974. Another expedition confirmed it with photos and video from a research submarine.

These photos showed the wreck was falling apart. To protect it, a special area was created. It was called the Monitor National Marine Sanctuary. This was the first U.S. marine sanctuary. The Monitor was also named a National Historic Landmark in 1986.

In 1977, scientists finally saw the wreck in person using a submersible. Divers brought up small items. The U.S. Navy decided not to raise the whole ship. It would cost too much and might damage the wreck. Research continued, and more items were recovered. This included the ship's 1,500-pound (680 kg) anchor in 1983. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) chose the Mariners' Museum to keep and care for these items.

Bringing Up Parts of the Ship

In 1995, divers tried to raise the ship's propeller. But bad storms off Cape Hatteras stopped them. NOAA then made a plan to recover the most important parts of the ship. These included the engine, propeller, guns, and turret. This plan would cost over $20 million. Navy divers helped with the work.

Another try to raise the Monitor's propeller was successful on June 8, 1998. The work was very difficult. In 1999, divers studied the wreck to plan how to recover the engine. In 2000, they prepared the hull to prevent it from collapsing.

The 2001 dive season focused on raising the ship's steam engine and condenser. Divers had to remove hull plates to reach the engine. The engine was raised on July 16. The condenser was raised three days later.

In 2002, the goal was to lift the 120-long-ton (120 t) turret. Divers removed parts of the hull that were on top of the turret. They used special tools to cut and clean inside the turret. They found one skeleton in the turret on July 26. They carefully worked to free half of it.

A large lifting frame, called the "spider," was placed over the turret. On August 5, 2002, the turret was lifted. It broke the surface at 5:30 pm to cheers. As archaeologists looked inside the turret, they found a second skeleton. The remains of these sailors were sent to a special lab to try and identify them.

Only 16 crew members were not rescued when the Monitor sank. Scientists tried to identify the two skeletons. They ruled out the three missing black crewmen based on bone shapes. After a decade, their identities were still unknown. On March 8, 2013, their remains were buried at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors.

In 2003, divers returned to record the wreck's condition. They found the Monitor's iron pilot house near the front of the ship. It was upside down.

The propeller's restoration was finished in 2005. It is now on display at the Mariners' Museum. As of 2013, the engine, turret, and guns are still being preserved. The Dahlgren guns were removed from the turret in 2004. A red signal lantern, possibly the one used to send a distress signal, was found in 1977. A gold wedding band was also found on one of the skeletons in the turret.

A full-size replica of the Monitor was built in Newport News. It was finished in 2005 and is at the Mariners' Museum. Divers still visit the wreck to check its condition.

Remembering the Monitor

A monument to the Monitor is in McGolrick Park, Brooklyn. It shows a sailor from the Monitor. It was made to remember the Battle of Hampton Roads, John Ericsson, and the ship's crew. It was dedicated on November 6, 1938.

In 1995, the U.S. Postal Service made a stamp. It showed the USS Monitor and CSS Virginia fighting.

The 150th anniversary of the ship's sinking was remembered with several events. A memorial for the Monitor and its lost crew was put up in the Civil War section of Hampton National Cemetery. It was dedicated on December 29, 2012. The Greenpoint Monitor Museum also held an event at the graves of Monitor crew members buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn.

The band Titus Andronicus named their 2010 album The Monitor after the ship. The album cover shows the Monitor's crew. The album has many references to the Civil War, including a song called "The Battle of Hampton Roads."

The Monitor's Impact

The Monitor gave its name to a new type of warship. These ships had no tall masts and a low deck. Their guns were in spinning turrets. Many more monitors were built. They played important roles in Civil War battles on rivers.

Later, a new design called the "breastwork monitor" was created. These ships had a raised area on deck to make them better in rough seas. This area also protected the base of the gun turrets. These ships were meant for harbor defense. They had one twin-gun turret at each end. These ships were like "full-armoured knights riding on donkeys."

This design led to even bigger and more powerful ships. These were the first ocean-going turret ships without masts. They were the direct ancestors of the huge battleships that came later.

See also

In Spanish: USS Monitor para niños

In Spanish: USS Monitor para niños

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |