Franklin–Nashville campaign facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Franklin–Nashville campaign |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

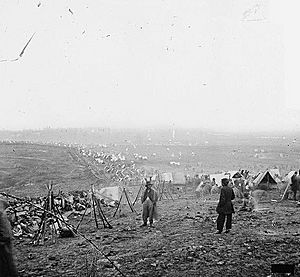

Union army at Nashville, Tennessee, December, 1864 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| George H. Thomas John Schofield |

John Bell Hood | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Army of the Cumberland Army of the Ohio |

Army of Tennessee | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

||||||

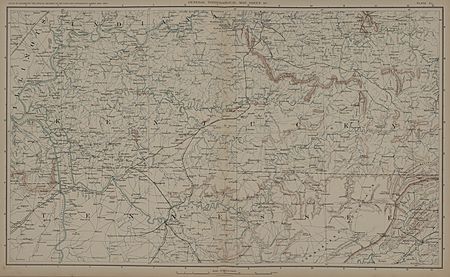

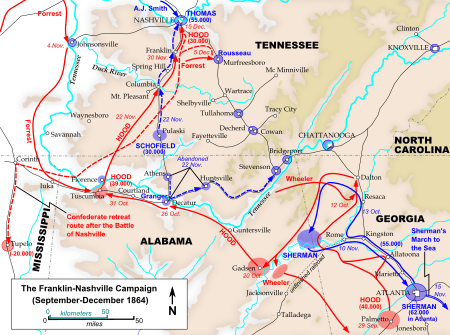

The Franklin–Nashville campaign was a series of important battles during the American Civil War. It happened from September to December 1864. These battles took place in Alabama, Tennessee, and parts of Georgia. This campaign was part of the war's "Western Theater," which means the fighting happened west of the Appalachian Mountains.

The Confederate Army of Tennessee, led by Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood, marched north from Atlanta. Hood hoped to cut off the supply lines of the Union forces. He also wanted to threaten central Tennessee.

Union Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman briefly chased Hood. But then Sherman decided to focus on his famous "Sherman's March to the Sea." He left Maj. Gen. George Henry Thomas in charge of stopping Hood.

Hood tried to defeat a Union force under Maj. Gen. John Schofield before it could join Thomas's army. This led to the Battle of Spring Hill on November 29. But poor planning by the Confederates allowed Schofield to escape. The next day, Hood launched many attacks at the Battle of Franklin. His army suffered huge losses. Schofield then successfully joined Thomas in Nashville, Tennessee.

On December 15–16, Thomas's combined army attacked Hood's weakened army. This was the Battle of Nashville. Hood's army was completely defeated and forced to retreat. Hood soon resigned, and his army was no longer a strong fighting force. This campaign marked the end of major battles in the Western Theater.

Contents

- Why the Campaign Started

- The Armies Involved

- Hood Attacks Sherman's Supply Line

- Forrest's Raid in West Tennessee (October 16 – November 16)

- Decatur (October 26–29)

- Columbia (November 24–29)

- Spring Hill (November 29)

- Battle of Franklin (November 30)

- Chasing Hood to Nashville

- Battle of Nashville (December 15–16)

- Retreat and Chase

- What Happened Next

- Images for kids

Why the Campaign Started

After his success in the Atlanta campaign, General Sherman took control of Atlanta on September 2, 1864. The Confederate General Hood had to leave the city. He then gathered his troops at Lovejoy's Station. For about a month, Sherman didn't do much. Many of his soldiers left the army when their time was up.

On September 21, Hood moved his army to Palmetto, Georgia. There, on September 25, he met with Confederate President Jefferson Davis. They made a plan for Hood to move towards Chattanooga, Tennessee. His goal was to attack Sherman's supply lines. They hoped Sherman would follow. Then Hood could fight Sherman on ground that favored the Confederates.

President Davis was not happy with Hood's performance in the Atlanta campaign. Hood had lost many men in attacks that didn't gain much. Davis even thought about replacing Hood. But after Davis left, he decided to keep Hood in command. He also moved one of Hood's commanders, Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee, out of the army.

Sherman was planning to march east to capture Savannah, Georgia. This would become known as Sherman's March to the Sea. But he was worried about his supply lines back to Chattanooga. A Confederate cavalry leader named Nathan Bedford Forrest was a big threat. Forrest was known for his fast raids behind Union lines. On September 29, Union General Ulysses S. Grant told Sherman to deal with Forrest. Sherman sent General Thomas to Nashville to organize troops there.

Sherman knew some of Hood's plans. President Davis had given speeches predicting Hood's success. These speeches were reported in newspapers that Sherman read. In one speech, Davis said Hood would attack Sherman's supply lines. He even hoped to plant Confederate flags on the banks of the Ohio River.

The Armies Involved

Let's look at the two main armies that fought in this campaign.

Confederate Forces

| Principal Confederate commanders |

|---|

|

Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood led the Confederate Army of Tennessee. It had about 39,000 men. This was the second-largest Confederate army left. Only General Robert E. Lee's army was bigger.

Hood's army had three main groups, called corps. They were led by Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Cheatham, Lt. Gen. Stephen D. Lee, and Lt. Gen. Alexander P. Stewart. The cavalry (soldiers on horseback) was led by Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest. Even though the soldiers were not well-clothed, they had good weapons.

Union Forces

| Principal Union commanders |

|---|

|

At first, General Sherman was in charge of all Union forces in the area. But he left in October. After that, Maj. Gen. George Henry Thomas became the main Union commander. He was known as the "Rock of Chickamauga."

Thomas had the Army of the Cumberland. Maj. Gen. John Schofield led the Army of the Ohio. This army had about 34,000 men. It included the IV Corps and the XXIII Corps. Maj. Gen. James H. Wilson led the cavalry. Thomas also had another 26,000 men in Nashville and other places.

Hood Attacks Sherman's Supply Line

Hood's plan seemed to be working. Sherman had to spread out his troops to protect his supply lines. But Sherman didn't fall completely into Hood's trap. He planned to give Thomas enough soldiers to fight Hood and Forrest. Meanwhile, Sherman would prepare his march to Savannah.

On September 29, Hood began to move his 40,000 men northwest. He wanted to threaten the Western and Atlantic Railroad, which was Sherman's supply line. On October 1, Hood's cavalry fought Union cavalry near Marietta. But Sherman still wasn't sure where Hood was going. For three weeks, Sherman had trouble tracking Hood. Hood moved quickly, hid his marches, and stayed in control.

On October 3, Hood's troops captured Big Shanty and Acworth. Sherman left some troops in Atlanta and moved towards Marietta with about 55,000 men. Hood split his army. Most went to Dallas, Georgia. A smaller group went to Allatoona to attack the railroad.

Battle of Allatoona (October 5)

The Union army had a small group of soldiers defending Allatoona. They were led by Col. John Tourtellotte. Sherman sent more troops under Brig. Gen. John M. Corse, who took command. The Union soldiers had strong defenses. They were in two dirt forts on each side of a deep railroad cut. Many of them had powerful Henry repeating rifles.

Confederate Maj. Gen. Samuel Gibbs French's troops arrived on October 5. After two hours of artillery fire, French demanded surrender. Corse refused. French then attacked from the north and west. Corse's men fought hard for two hours. They were almost forced to give up. But then French heard a false report that a large Union force was coming. So, he pulled his troops back. Allatoona was a small but bloody battle with many casualties.

Moving into Alabama

Hood then moved west and crossed the Coosa River near Rome, Georgia. He turned north towards Resaca, Georgia. On October 12, Hood demanded that the Union soldiers at Resaca surrender. He warned that no prisoners would be taken. But the Union commander, Col. Clark R. Weaver, refused. He said, "If you want it, come and take it." Hood decided not to attack because it would cost too many lives. Instead, he went around the city and kept destroying the railroad.

Sherman learned where Hood was and sent more troops to Resaca. But they arrived too late to fight Hood. Hood sent Lt. Gen. Alexander P. Stewart even further north to Tunnel Hill. Stewart was to destroy as much railroad as possible. On October 13, Stewart captured the Union soldiers at Dalton, Georgia.

This capture was very bad. The 751 Union soldiers included many African-American soldiers. This made many in Hood's army angry. During surrender talks, the Union commander, Col. Lewis Johnson, insisted his black troops be treated as prisoners of war. But Hood said that "all slaves" would be returned to their owners. Johnson had to surrender. About 600 black soldiers were forced to march and tear up railroad tracks. Six of them were shot for refusing to work or for not keeping up. Colonel Johnson later said the abuse was the worst he had ever seen. Johnson and his white officers were released. But some of his black soldiers were returned to slavery.

From Resaca, Hood marched west for six days to Gadsden, Alabama. He arrived on October 20. He had hoped to fight Sherman near LaFayette, Georgia. But his commanders convinced him their troops were not ready for an attack. Hood thought his campaign was successful because he destroyed 24 miles of railroad. But this didn't last long. Sherman used 10,000 men to rebuild the railroad. By October 28, trains were running again between Chattanooga and Atlanta. Sherman only chased Hood as far as Gaylesville, Alabama.

Hood then focused his plan. He needed to stop Thomas's army from joining Sherman. He thought if he moved quickly into Tennessee, he could defeat Thomas before Union forces could gather. After beating Thomas, Hood planned to go into Kentucky to get more soldiers. He hoped to do all this before Sherman could reach him. If Sherman followed, Hood would fight him in Kentucky. From there, he planned to go east to help Robert E. Lee at Petersburg.

On October 21, Hood's plan was approved by Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard, though Beauregard was worried about getting supplies. Beauregard said Forrest's cavalry should join Hood. Hood then headed towards Decatur, Alabama. He planned to meet Forrest near Florence. From there, they would march north into Tennessee.

Sherman learned that Grant was thinking about the march to Savannah. So, Sherman focused on chasing Hood. He told Thomas to move from Nashville to block Hood. To help Thomas, Sherman sent the IV Corps and XXIII Corps to Nashville. He also sent the XVI Corps from Missouri to Nashville. By November 10, the rest of Sherman's troops were heading back to Atlanta.

Forrest's Raid in West Tennessee (October 16 – November 16)

One important Union supply route in Tennessee used the Tennessee River. Supplies were unloaded at Johnsonville and then sent by train to Nashville. Confederate Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor ordered Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest to raid Western Tennessee. His goal was to destroy this supply line.

Forrest's men started riding on October 16. Forrest himself began moving north on October 24. He reached Fort Heiman on the Tennessee River on October 28. There, he set up cannons. On October 29 and 30, his cannons helped capture three steamboats and two gunboats. Forrest fixed two of the boats, the Undine and Venus. He planned to use them to attack Johnsonville.

On November 2, Union gunboats challenged Forrest's small fleet. The Venus ran aground and was captured. The Union sent six more gunboats. On November 3, they fought with Confederate cannons near Johnsonville. The Union fleet had trouble defeating these positions. This gave Forrest time to prepare his attack on Johnsonville.

On November 4, the Undine and the Confederate cannons were attacked by Union gunboats. The Undine was set on fire and exploded. This ended Forrest's short time as a naval commander. But the Confederate land cannons were very good at stopping the Union boats. Forrest's cannons fired at the Union supply depot. They hit 28 steamboats and barges at the dock. All three Union gunboats were damaged or destroyed. The Union commander ordered the supply ships to be burned so the Confederates couldn't capture them.

Forrest caused huge damage with very few losses. He reported only 2 men killed and 9 wounded. He said the Union lost 4 gunboats, 14 transports, 20 barges, and property worth millions of dollars. Forrest's troops then moved to Perryville, Tennessee. They finally reached Corinth, Mississippi, on November 10. During the raid, on November 3, Forrest's cavalry was assigned to Hood's army. Hood decided to wait for Forrest to join him before moving north into Tennessee. Forrest linked up with Hood on November 16.

Decatur (October 26–29)

Hood left Gadsden on October 22. He planned to cross the Tennessee River at Guntersville, Alabama. But he learned that crossing was heavily guarded. He also worried that Union gunboats could destroy any bridge he built. So, he suddenly changed his plan. He decided to go to Decatur, 40 miles west.

When Hood arrived at Decatur on October 26, he found a Union force of 3,000 to 5,000 men. They were defending strong lines with two forts and rifle pits. Two Union gunboats were on the river. On October 28, Confederate soldiers moved through a thick fog. They got close to the main forts. Around noon, a small Union group drove them back. They captured 125 men. Hood decided he couldn't afford to lose so many men in a full attack. So, he pulled his army back. He decided to move west again. He would try to cross the river near Tuscumbia, Alabama. There, Muscle Shoals would stop Union gunboats.

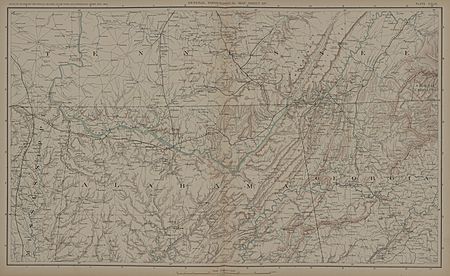

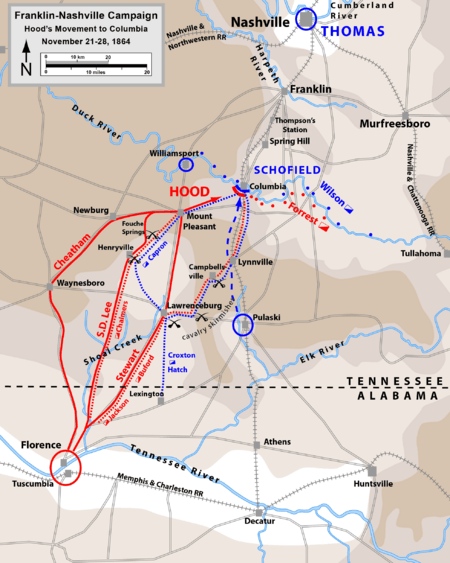

Columbia (November 24–29)

Hood waited for Forrest at Tuscumbia for almost three weeks. His officers tried to get 20 days of food for the army. This was hard because supplies had to travel by two railroads. Then they had to go 15 miles on bad roads to Tuscumbia. Wagons were pulled by tired horses and oxen.

Hood moved his headquarters to Florence on November 13. Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Cheatham's corps crossed the river that day. The army's supplies and cattle followed. The last corps, under Lt. Gen. Alexander P. Stewart, crossed the Tennessee River on November 20.

On November 16, Hood heard that Sherman was leaving Atlanta for his March to the Sea. General Beauregard told Hood to act quickly. He wanted Hood to distract Sherman. He stressed how important it was to move before Thomas could gather his forces. Both Sherman and Thomas thought Hood would follow Sherman through Georgia. Thomas heard that Hood was getting supplies for a move north. But he didn't believe most of it. Heavy rains in November made the roads almost impossible to use.

However, by November 21, Thomas had proof that all three of Hood's corps were moving. He told Schofield to slowly pull back north. Schofield needed to protect Columbia before Hood could take it. Schofield arrived at Pulaski on November 13. He took command of all troops there, including the IV Corps. Thomas was still worried that 10,000 troops from the XVI Corps had not arrived from Missouri.

Hood's army left Florence on November 21. They marched in three columns. Cheatham was on the left, Lee in the center, and Stewart on the right. Forrest's cavalry rode in front to hide their movements. Hood planned to gather his forces at Mount Pleasant. From there, he would move east to cut off Schofield before he could reach Columbia and the Duck River. The 70-mile march north was very hard. There were freezing winds and sleet. The soldiers were underfed and didn't have enough clothes. But Hood's men were happy to be back in Tennessee.

Schofield didn't know where the Confederate army was going because of Forrest's constant scouting. Forrest had a small advantage over Union cavalry leader Maj. Gen. James H. Wilson. Wilson had arrived in late October to lead Thomas's cavalry. But he only had 4,800 horsemen to fight Forrest's 5,000 to 6,000 men. The Confederate cavalry reached Mount Pleasant by November 23.

Forrest kept up the pressure. On November 23, there was heavy fighting from Henryville to Mount Pleasant. Forrest's divisions pushed Union troops back towards Pulaski. Early on November 24, Schofield began marching his two infantry corps north to Columbia. Forrest chased them hard. He captured Mount Pleasant and kept attacking Union troops. But the Confederate cavalry could not stop Union troops from reaching Columbia. Stanley's corps marched 30 miles to help Schofield. Together, they started building trenches south of the town.

On November 24, Forrest's cavalry began small attacks. They tried to break through the Union defenses. The Confederates fired cannons. But it became clear that only a small part of Hood's army was attacking. Hood was just pretending to attack. He planned to cross the Duck River somewhere else. He wanted to cut off the Union force from Thomas, who was gathering his army in Nashville.

On November 26, Schofield received orders from Thomas. He was to hold the north bank of the Duck River until more troops arrived from Nashville. Schofield planned to move his supply wagons during the day. He would move his soldiers overnight. They would use a railroad bridge and a new pontoon bridge. But heavy rains made the paths to the bridge impassable. That evening, most of Hood's army reached the defenses south of Columbia.

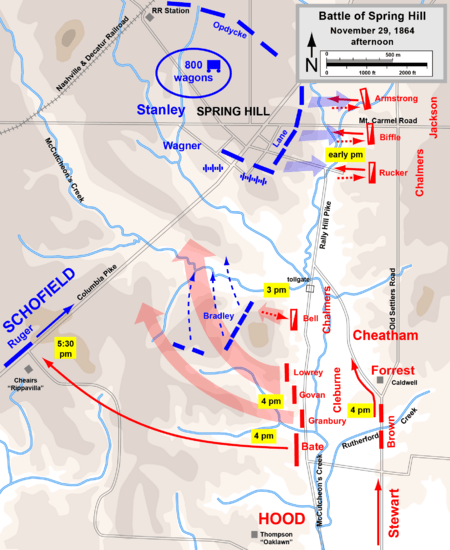

Spring Hill (November 29)

On November 28, Forrest crossed the river east of Columbia. There was little Union resistance. The Southern cavalry had tricked Wilson and drawn his forces away. On the same day, Thomas told Schofield to get ready to pull back north to Franklin. Thomas thought more Union troops would arrive soon. He wanted the combined force to defend against Hood at Franklin.

Schofield sent his 800-wagon supply train ahead. It was guarded by part of the IV Corps. On November 29, Hood sent Cheatham's and Stewart's corps on a march north. They crossed the Duck River east of Columbia. Two divisions of Lee's corps and most of the army's cannons stayed south of the river. They pretended to attack Columbia. Hood, riding with Cheatham's corps, planned to get his army between Schofield and Thomas. He hoped to defeat Schofield as the Union troops retreated.

Cavalry fights between Wilson's and Forrest's troops continued all day. Forrest's 4,000 cavalrymen had forced Wilson north. This stopped the Union cavalry from interfering with Hood's infantry. By 10 a.m., Forrest ordered his men to turn west towards Spring Hill. Wilson sent many messages to Schofield warning of Hood's advance. But it wasn't until dawn on November 29 that Schofield believed the reports. He realized he was in danger. He sent Stanley north with parts of the IV Corps. Stanley was to protect the supply trains. He also had to hold the crossroads at Spring Hill. This would allow the whole army to retreat safely to Franklin.

Forrest's cavalry met Union pickets (guards). Stanley had moved north quickly. He set up defenses around Spring Hill. A Union brigade pushed back the Confederate cavalry. Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne's division arrived in the afternoon. The cavalry, low on ammunition, moved north to cover Hood's advance.

The first mistake in communication happened when Hood arrived. Cheatham had ordered his division to attack Spring Hill with Cleburne. But Hood personally told them to move towards the Columbia Pike. He wanted them to "sweep toward Columbia." Neither Hood nor the division commander told Cheatham about this change. Around 5:30 p.m., the Confederate troops fired on a Union column. This was the front of Schofield's main army. But before the two sides could fight, an officer from Cheatham's staff arrived. He insisted the division follow Cheatham's original orders. Later that night, the division commander reported seeing the Union column. But Cheatham didn't think it was important.

Back in Columbia, Schofield became sure that the Confederates would not attack him there. Around 3 p.m., he began marching his men to Spring Hill. As soon as the first units left, the Confederates began an attack on the Union position. But by the time most of the Confederate troops could cross, the Union general in charge at Columbia began his retreat. The last troops left by 10 p.m.

Cleburne's 3,000 men attacked a Union brigade around 4 p.m. Cheatham expected Cleburne to attack north into Spring Hill. But Hood wanted them to sweep towards the main road and turn left to stop Schofield's arriving troops. Cleburne's brigades turned north. They attacked the Union flank, causing the Union troops to run away. Cleburne's brigades chased them. But they were stopped by heavy fire from Union cannons.

By this time, another Confederate division was in position for another attack on Spring Hill. But they didn't attack. They reported Union troops on their right side. Also, Forrest's cavalry, who were supposed to protect their right, didn't seem to be there. The commander decided to talk to his corps commander before attacking. By the time they talked, it was completely dark. They decided that an attack in the dark, without knowing what was on their right, could be a disaster. Hood was furious that the attack hadn't happened. The main road was still open. He sent an officer to find Stewart to help Cheatham. Hood had been up since 3 a.m. He went to bed at 9 p.m. He was sure that his army would capture Schofield in the morning.

The Battle of Spring Hill was small in terms of casualties. About 350 Union and 500 Confederate soldiers were lost. But it was a huge failure due to bad communication and poor leadership. During the night, all of Schofield's army passed through Spring Hill. The Confederate commanders were sleeping. Some Confederate soldiers noticed the Union army moving. But no one made a strong effort to block the road. Confederate cavalry tried to block the supply trains north of Spring Hill. But Union infantry drove them away. A private soldier woke up the general at 2 a.m. and said he saw the Union column moving. But Hood did nothing. He only sent a message to Cheatham to fire on passing traffic.

By 6:00 a.m. on November 30, all of Schofield's army was far north of Spring Hill. The first troops had reached Franklin. They began to build defenses south of the town. In the morning, Hood found out Schofield had escaped. He was very angry. He blamed everyone but himself for the failure. He ordered his army to chase Schofield. Spring Hill was Hood's best chance to trap and defeat the Union army. Hood believed Cheatham was mostly to blame. But historians say both Hood and Cheatham were at fault.

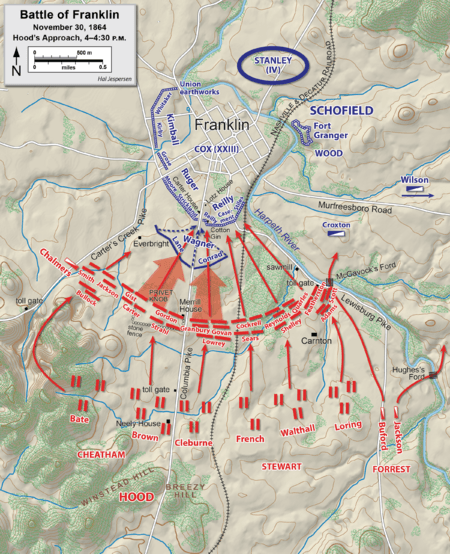

Battle of Franklin (November 30)

Schofield's first troops arrived in Franklin around 4:30 a.m. on November 30. Jacob Cox, a division commander, immediately started preparing strong defenses. These were built on old trenches from a previous battle in 1863. Schofield decided to defend Franklin with his back to the river. He had no bridges to cross the river. Schofield needed time to fix the permanent bridges. But by mid-afternoon, almost all the supply wagons were across the Harpeth River and on the road to Nashville. By noon, the Union defenses formed a half-circle around the town. There was a gap in the line where the Columbia Pike entered the town. This was left open for the wagons. Just behind the center of the strong line was the Carter House. This was used as Cox's headquarters.

Two Union brigades were about half a mile in front of the main line. Their commander, General Wagner, ordered them to stop halfway and dig in. But Col. Emerson Opdycke thought this was a bad idea. He refused the order. He marched his brigade through the Union line. He put them in a reserve position behind the gap in the defenses. This left two other brigades in front.

Hood's army arrived on Winstead Hill, two miles south of Franklin, around 1 p.m. Hood ordered a direct attack in the fading daylight. The sun would set at 4:34 p.m. that day. This decision shocked his top generals. Some stories say Hood acted rashly because he was angry that the Union army had escaped at Spring Hill. They say he wanted to punish his army by making them attack against tough odds. But recent studies say this is unlikely. Hood was seen as determined, not angry, when he arrived in Franklin.

Hood's goal was to crush Schofield before he could escape to Nashville. The Confederates began moving forward at 4 p.m. Cheatham's corps was on the left, and Stewart's was on the right. Lee's corps and most of the army's cannons had not yet arrived from Columbia. Hood's attacking force was about 19,000 to 20,000 men. This was probably not enough for the mission. They had to cross two miles of open ground with only two artillery batteries. Then they had to attack strong defenses.

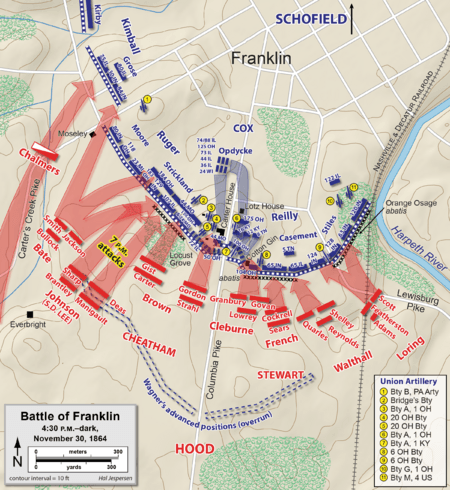

Hood's attack first hit the 3,000 men in the two brigades in front. These brigades tried to hold their ground behind weak defenses. But they quickly broke under the pressure. Many experienced soldiers ran back to the main defenses. Some new soldiers were afraid to move under fire and were captured. The Confederates chased the fleeing troops very closely. The two sides got so mixed up that the Union defenders had to stop firing to avoid hitting their own men.

The Union's temporary inability to defend the opening in their defenses created a weak spot. This was at the Columbia Pike, from the Carter House to the cotton gin. Confederate divisions attacked this area. Many of their troops broke through the Union defenses. In minutes, the Confederates had pushed 50 yards into the center of the Union line.

As the Confederates attacked, Opdycke's brigade was in reserve. He quickly put his men in battle formation. He ordered his brigade forward to the defenses. Hand-to-hand fighting around the Carter House was fierce. Firing continued for hours. Many Confederates were pushed back to the Union defenses. Many were stuck there for the rest of the evening. They couldn't advance or run away.

While fighting raged in the center, Stewart's Corps also attacked the Union left. The Harpeth River made the area narrower. This squeezed the Confederate brigades together. It slowed them down and made them less organized. They faced heavy artillery fire from the Union line and from Fort Granger across the river. They also had trouble getting through strong obstacles made of thorny bushes.

One Confederate division launched two attacks. Both were pushed back with heavy losses. Cannons firing special rounds directly down the railroad cut stopped any attempts to go around the Union position. One Confederate general tried to rally his brigade by riding his horse onto the defenses. But he and his horse were both shot and killed. Another brigade started to fall back under heavy fire. Their commander confronted them, shouting, "Great God! Do I command cowards?" He tried to inspire his men by sitting on his horse in full view of the Union lines. He was unharmed, but the brigade made no more progress. Another Confederate division attacked the Union brigades in many waves. All these attacks were pushed back with heavy losses.

Maj. Gen. William B. Bate's division attacked on the Union right side. His left side was not protected by cavalry as he expected. They were hit by fire from the side. To protect the side, Bate ordered a brigade to move from its reserve position to his left. This slowed the attack. It also meant there was only one line attacking the Union defenses, with no reserve. The Confederate cavalry had actually engaged the Union right by this time. But Bate didn't know it. Neither Bate nor the cavalry made any progress, and they pulled back.

Hood still believed he could break the Union line. Around 7 p.m., he sent the only division of Lee's corps that had arrived to help Cheatham. They were pushed back after one attack with heavy losses.

Across the river to the east, Confederate cavalry commander Forrest tried to go around the Union left. Union cavalry commander Brig. Gen. James H. Wilson learned at 3 p.m. that Forrest was crossing the river. He ordered his division to move south and attack Forrest. He also ordered another brigade to attack Forrest's side. The Union cavalry charged the Confederate cavalry and drove them back across the river.

After this last attack failed, Hood decided to stop fighting for the night. He began planning for more attacks in the morning. Schofield ordered his infantry to cross the river, starting at 11 p.m. There was a time when the Union army was vulnerable, outside its defenses and crossing the river. But Hood did not try to take advantage of it during the night. The Union army began entering the defenses at Nashville at noon on December 1. Hood's damaged army followed them.

The Confederate army was left in control of Franklin. But their enemy had escaped again. Hood had almost broken through the Union line. But he could not destroy Schofield or stop him from joining Thomas in Nashville. This failure came at a terrible cost. The Confederates suffered 6,252 casualties. This included 1,750 killed and 3,800 wounded. About 2,000 others had less serious wounds. But more importantly, many Confederate leaders were lost. This included Patrick Cleburne, who was one of the best division commanders. Fourteen Confederate generals were casualties. Six were killed or mortally wounded, seven were wounded, and one was captured. Fifty-five regimental commanders were also lost.

Union losses were much lower. They reported only 189 killed, 1,033 wounded, and 1,104 missing. It's possible the number of Union casualties was under-reported. This is because of the confusion during their fast nighttime escape from Franklin. The Union wounded were left behind in Franklin.

Chasing Hood to Nashville

The Confederate Army of Tennessee was almost destroyed at Franklin. But Hood decided to advance his 26,500 men against the Union army. Thomas now had about 55,000 men. They were strongly dug in at Nashville. This was a risky move for Hood. His army was tired and not ready for more attacks. But he believed that if he ordered a retreat, his army would completely fall apart.

Hood decided that destroying the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad would help. He also wanted to disrupt the Union supply depot at Murfreesboro. On December 4, he sent Forrest with two cavalry divisions and one infantry division to Murfreesboro. Hood ordered them to destroy the railroad and blockhouses.

Forrest at Murfreesboro (December 5–6)

Forrest's troops attacked Murfreesboro but were pushed back. They destroyed railroad tracks, blockhouses, and some homes. They caused problems for Union operations in the area. But they didn't achieve much else. The raid on Murfreesboro was a small annoyance. The infantry division was called back to Nashville. But Forrest stayed near Murfreesboro. This meant he was not at the Battle of Nashville. Looking back, Hood's decision to send Forrest away was a big mistake.

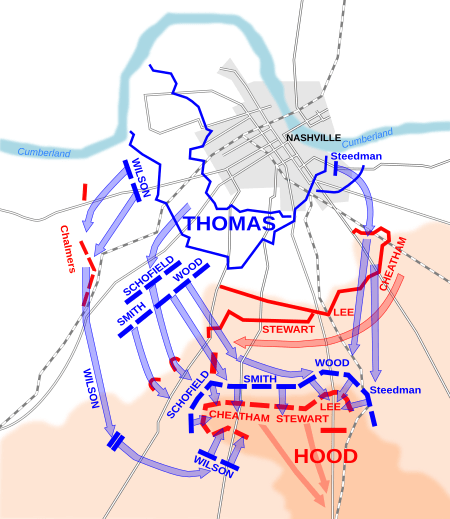

Battle of Nashville (December 15–16)

General Thomas now commanded about 55,000 Union soldiers. Their defensive line around Nashville was 7 miles long and shaped like a half-circle. The rest of the circle, to the north, was the Cumberland River. U.S. Navy gunboats patrolled the river.

It took Thomas over two weeks to move. This made Washington very worried. They thought Hood was about to invade the North. General Grant pressured Thomas to move. A bad ice storm hit on December 8. It stopped much of the work on defenses for both sides. A few days later, Grant sent an aide to take command from Thomas. Grant believed Hood would escape. But on December 15, the Battle of Nashville finally began.

Thomas finally left his defenses on December 15. He started a two-part attack on the Confederates. The first, smaller attack was on the Confederate right side. The main attack would be on the enemy's left. This attack moved left, parallel to the Hillsboro Pike. By noon, the main attack reached the pike. Union troops prepared to attack Confederate outposts on Montgomery Hill. Hood became worried about his left side. He ordered Lee to send more troops to Stewart. Union troops took Montgomery Hill in a charge.

Around 1 p.m., there was a weak point in Hood's line. Thomas ordered an attack on this point. By 1:30 p.m., Stewart's position became impossible to hold. The attacking Union force was too strong. Stewart's corps broke and began to retreat. However, Hood was able to regroup his men by nightfall. He prepared for the battle the next day. The Union cavalry had not been able to block the main road. Many of their soldiers were fighting on foot in the attack. The tired Confederates dug in all night. They waited for the Union troops to arrive.

It took most of the morning on December 16 for the Union troops to get into position. Hood's new line was only about 2 miles long. Again, Thomas planned a two-part attack. But he focused on Hood's left side. Schofield was to push back Cheatham. Wilson's cavalry was to swing around to block the Franklin Pike. This was Hood's only way to retreat. At noon, Union troops attacked Lee on Overton's Hill. But they were not successful. On the left, Wilson's cavalry was putting pressure on the line.

At 4 p.m., Cheatham's corps was attacked from three sides. They broke and ran to the rear. Union troops took this chance to attack Lee on Overton's Hill again. This time, the attack was too strong. Darkness fell, and heavy rain began. Hood gathered his forces and retreated south towards Franklin.

Casualties from the two-day battle were 3,061 Union soldiers. This included 387 killed, 2,558 wounded, and 112 missing or captured. The Confederates had about 6,000 casualties. This included 1,500 killed or wounded, and 4,500 missing or captured. The Battle of Nashville was one of the Union Army's greatest victories in the war. The strong Confederate Army of Tennessee was effectively destroyed as a fighting force. Hood's army entered Tennessee with over 30,000 men. But it left with only 15,000 to 20,000.

Retreat and Chase

The Union army chased Hood from Nashville. The rainy weather helped the Confederates. It slowed down the Union cavalry. Forrest was able to rejoin Hood on December 18. He helped protect the retreating army. The chase continued until Hood's beaten army crossed the Tennessee River on December 25. On Christmas Eve, Forrest fought off Wilson's chasing cavalry.

What Happened Next

Hood blamed his commanders and soldiers for the disaster. But his career was over. He retreated with his army to Tupelo, Mississippi. He resigned his command on January 13, 1865. He was never given another command in the field. Forrest returned to Mississippi. But in 1865, he was driven into Alabama. His command became scattered and ineffective.

By the time Hood was defeated in Nashville, Sherman's army had reached Savannah, Georgia. They captured it just before Christmas. Five thousand men from the Army of Tennessee later fought under Joseph E. Johnston against Sherman in South Carolina. But it was no use.

Images for kids