Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

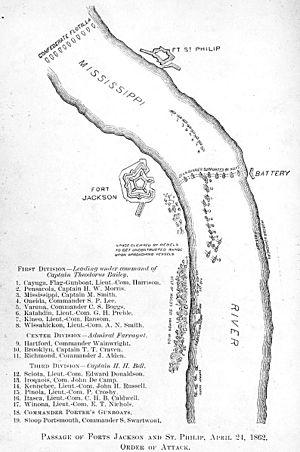

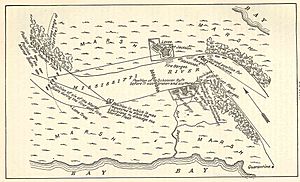

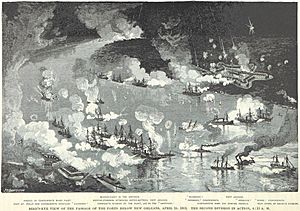

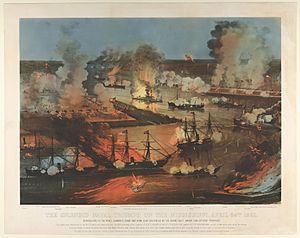

Attack of the Union fleet, April 24, 1862; Fort Jackson at left and Fort St. Philip is shown at right |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| David G. Farragut | Johnson K. Duncan John K. Mitchell John A. Stephenson |

||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| West Gulf Blockading Squadron | Fort Jackson Fort St. Philip River Defense Fleet |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 229 | 782 | ||||||

The Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip was a key battle during the American Civil War. It happened from April 18 to 28, 1862. This battle decided who would control New Orleans, a very important city for the Confederacy. Two Confederate forts, Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip, guarded the Mississippi River south of the city. If these forts could stop the Union Navy, New Orleans would be safe. If they fell, the city would be open to attack.

New Orleans was the biggest city in the Confederacy. It was already facing threats from the north. But then, a Union fleet led by David Farragut moved into the river from the south. The Confederacy had moved many soldiers and much equipment away from New Orleans. This was to help with battles in Kentucky and Tennessee. By mid-April, only the two forts and some weak gunboats were left to defend the city from the south.

To attack from the south, Union President Abraham Lincoln planned a joint Army-Navy operation. The Union Army sent 18,000 soldiers, led by General Benjamin F. Butler. The Navy sent a large part of its West Gulf Blockading Squadron. This fleet was commanded by Flag Officer David G. Farragut. Another group of mortar schooners, led by Commander David Dixon Porter, also joined the attack.

The Union forces gathered at Ship Island in the Gulf of Mexico. Once ready, the naval ships moved into the Mississippi River by April 14. They then took positions near the forts. On April 18, the mortars began firing, starting the battle.

The battle had two main parts. First, there was a long bombardment of the forts by Union mortars. This attack was mostly ineffective. Second, Farragut's fleet successfully sailed past the forts on the night of April 24. During this daring move, one Union warship was lost, and three others turned back. Most Confederate gunboats were destroyed. After the fleet passed, New Orleans was captured easily. This was a huge blow to the Confederacy. The forts themselves surrendered later, after soldiers in Fort Jackson refused to fight anymore.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

Forts Jackson and St. Philip: River Guardians

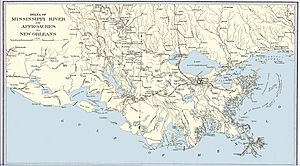

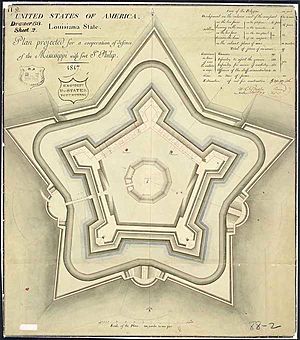

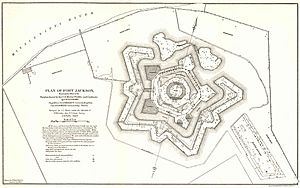

Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip were two forts built close together on the Mississippi River. They were about 40 kilometers (25 miles) upstream from where the river splits into different paths before reaching the Gulf of Mexico. They were also about 120 kilometers (75 miles) downstream from New Orleans. Fort Jackson was on the west bank, and Fort St. Philip was on the east bank.

These forts were designed to defend against old sailing ships. They were placed at a bend in the river. This forced ships to slow down as they passed. This made them easy targets for the forts' 177 guns.

Union Plans to Attack New Orleans

In 1861, a battle at Port Royal, South Carolina, showed that naval guns could damage forts. After this, Gustavus V. Fox, a Union Navy leader, pushed for attacking New Orleans from the Gulf. He thought mortars could weaken the forts. Then, a small army could attack the forts. After the forts were dealt with, a fleet could sail past them and attack New Orleans directly.

At first, General George B. McClellan of the Union Army disagreed. He felt that sending 30,000 to 50,000 troops to New Orleans would take away from his main plan to attack Richmond, Virginia. However, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles got General Benjamin F. Butler to support the plan. With Butler's help, Welles convinced President Abraham Lincoln to order the attack. Butler was put in charge of the land forces. He had 18,000 troops.

The Navy also made changes. On December 23, 1861, the Gulf Blockading Squadron was split. Captain David Glasgow Farragut was chosen to lead the West Gulf Blockading Squadron. He arrived at Ship Island on February 20, 1862, and the campaign began.

Farragut had to deal with a few challenges. He mostly ignored General Butler and his army's plans. Another challenge was David D. Porter, his foster brother. Porter led a group of mortar schooners. Farragut didn't think the mortars would work well, but he had to let Porter try.

In mid-March, Farragut started moving his ships over a sandbar at the river's mouth. The water was shallower than expected. One ship, USS Colorado, was too big to cross. This meant Farragut had fewer ships, and it also wasted time. After this, Farragut had six ships and twelve gunboats inside the river.

Porter's 26 mortar schooners entered the river easily. For the next month, Farragut studied the forts. He figured out the range of their guns and found other obstacles in the river. He placed the mortar boats in the best spots. On April 18, everything was ready.

Union Fleet Organization

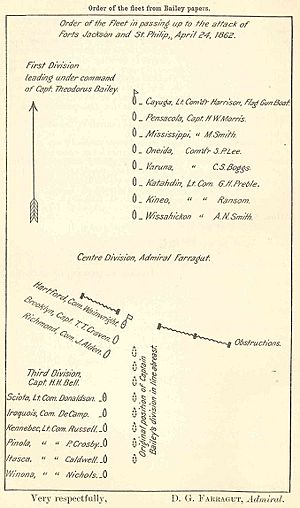

Farragut divided his fleet into three sections for the attack.

- The first section of gunboats was led by Captain Theodorus Bailey. He was also second in command.

- The second section of gunboats was led by Captain Henry H. Bell.

- Farragut himself led the main ships.

Confederate Defenses

Confederate leaders in Richmond believed the main threat to New Orleans came from the north. So, they sent many defenses to places like Island Number 10 and Fort Pillow. This actually weakened New Orleans's defenses. Soldiers were also moved away for other battles, like the one at Shiloh.

Major General Mansfield Lovell, who was in charge of the area, believed the threat from the Gulf was much greater. Flag Officer George N. Hollins, who led the Confederate naval forces on the Mississippi, agreed with Lovell. But his orders did not let him act on his beliefs. Hollins was later removed from active duty. Commander William C. Whittle took over the Confederate Navy ships near New Orleans. He then gave command of some ships to Commander John K. Mitchell.

Brigadier General Johnson K. Duncan commanded Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip. The soldiers in the forts were not the best. Many strong soldiers had been sent to other battles. The forts also had many foreign-born soldiers.

The Confederates also stretched two chains across the river to block ships. One was above the city and didn't affect the battle. The other was just below the forts. This chain was important because enemy ships trying to break it would be under fire from the forts. This barrier broke during spring floods but was repaired.

Several ships and boats also defended the river. These were from three different groups, with no single commander.

- The Confederate States Navy had three ironclads: CSS Manassas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. They also had two converted merchant ships: CSS McRae and Jackson.

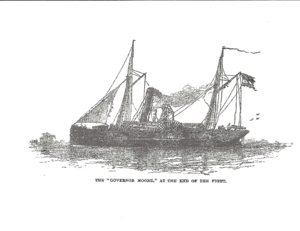

- The state of Louisiana had two ships: General Quitman and Governor Moore.

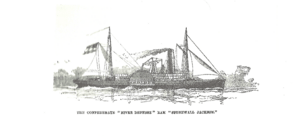

- The River Defense Fleet had six cottonclad rams: Warrior, Stonewall Jackson, Defiance, Resolute, General Lovell, and General Breckinridge. These were part of the Army but had civilian captains.

General Lovell tried to make all ships take orders from Commander Mitchell. But Captain John A. Stephenson, who led the River Defense Fleet, refused. This was because his fleet had a contract with the Army, not a military command.

The Battle Begins

First Phase: Mortar Bombardment (April 18-23)

On April 18, Porter's 21 mortar schooners were in place. They were hidden near the river banks, downstream from the barrier chain. They fired steadily all day. Porter wanted a shot every ten minutes from each mortar. This didn't happen, but over 1,400 shots were fired on the first day.

Many shells exploded too early. Porter ordered all fuses to be cut to full length. This made shells hit the ground before exploding. They would sink into the soft earth, which muffled the blast.

Fort Jackson was closer to the Union mortars and took more damage than Fort St. Philip. But even there, the damage was small. Only seven cannons were broken, and two men were killed. The forts' return fire was also not very effective. One Union schooner, USS Maria J. Carlton, was sunk, and one man was killed.

Porter had promised that the mortars would destroy the forts in 48 hours. This did not happen. However, Fort Jackson was badly damaged inside.

- All small boats near the fort were sunk.

- The drawbridge, furnaces, and water tanks were destroyed.

- The floors of the casemates (protected rooms) were flooded because the levee (river bank) broke.

- All tent platforms were burned.

- The outer walls of the fort cracked, letting daylight in.

- Four guns were dismounted, and many gun carriages were damaged.

- Thousands of mortar shells hit the fort and surrounding areas.

General Duncan, the Confederate commander of the forts, said that the living quarters inside and outside Fort Jackson burned down. The citadel (a strong central building) caught fire many times. Many soldiers lost their beds and clothes. The constant flooding made things worse. The mortar fire was "accurate and terrible."

Life in Fort Jackson became very hard. Soldiers could only find safety in the damp, flooded casemates. They lacked shelter, food, blankets, and clean water. This, along with sickness and constant fear, greatly lowered their spirits. These bad conditions led to the soldiers in Fort Jackson refusing to fight on April 28. This mutiny caused other Confederate defenses to collapse. Fort St. Philip also surrendered. The CSS Louisiana was blown up, and the Confederate fleet on Lake Pontchartrain was destroyed. The mutiny made it much easier for the Union Navy to take New Orleans.

The Confederates had hoped their ironclad ships, especially CSS Louisiana, would make the river impossible to pass. Louisiana was not finished, but Generals Lovell and Duncan pushed for her to be ready. She was launched early and joined Commander Mitchell's fleet. Workmen were still finishing her. She was towed upstream from Fort St. Philip. Her engines were too weak to move against the river current. She became a floating battery. Mitchell did not move her closer because her armor would not protect her from the mortars. Her guns also could not be raised, so they couldn't fire on the Union ships as long as they were below the forts.

After several days, the forts were still firing back. So, Farragut decided to act. On April 20, he sent three gunboats, Kineo, Itasca, and Pinola, to break the chain blocking the river. They didn't remove it completely, but they made a large enough gap for Farragut's fleet to pass.

Farragut waited until the early morning of April 24 to make his attack.

Second Phase: Passing the Forts

Farragut decided to sail past the forts. He changed his fleet's setup slightly.

- First section, Captain Theodorus Bailey: USS Cayuga, Pensacola (ship), USS Mississippi, Oneida, Varuna, Katahdin, Kineo, and Wissahickon.

- Second section (ships), Flag Officer Farragut: USS Hartford, Brooklyn, and Richmond.

- Third section, Captain Henry H. Bell: USS Sciota, Iroquois, Kennebec, Pinola, Itasca, and Winona.

The ship Portsmouth stayed behind to protect the mortar schooners.

When passing the forts, the fleet formed two lines. The ships on the right side would fire at Fort St. Philip. The ships on the left side would fire at Fort Jackson. They were not supposed to stop and fight the forts. Instead, they were to pass by as fast as possible. Farragut hoped the darkness and smoke would make it hard for the fort gunners to aim. This way, his ships could pass with little damage.

Around 3:00 AM on April 24, the fleet started moving towards the gap in the chain. Soon after passing it, the forts spotted them and opened fire. As Farragut hoped, their aim was poor, and his fleet was not badly damaged. The Union gunners' aim was also not great, so the forts were not damaged much either. The last three gunboats in the column turned back. Itasca was hit and drifted away. The others, Pinola and Winona, turned back because dawn was breaking.

The Confederate fleet did little during this part of the battle. CSS Louisiana finally fired her guns, but with little effect. The armored ram CSS Manassas tried to attack early. But the fort gunners fired at Manassas as well as the Union ships. So, her captain, Lieutenant Commander Alexander F. Warley, took his ship back upriver. He wanted to attack only the Union fleet.

Once past the forts, the front of the Union column was attacked by some Confederate ships. Other Union ships further back were still under fire from the forts. The Confederate ships did not work together. So, the battle became many small ship-on-ship fights.

CSS Manassas rammed both USS Mississippi and USS Brooklyn. But she did not disable either. As dawn broke, she was caught between two Union ships. Captain Warley ordered her to be run ashore. The crew left the ship and set it on fire. Later, she floated free, still burning, and sank near Porter's mortar schooners.

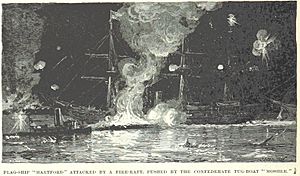

The tug CSS Mosher pushed a fire raft against Farragut's flagship, USS Hartford. Hartford fired back, sinking Mosher. While trying to avoid the fire raft, Hartford ran aground upstream from Fort St. Philip. The fort's guns couldn't reach her. So, Hartford put out the fire and got off the bank with little damage.

As Governor Moore started moving, she crashed into and sank the Confederate tug Belle Algerine. Governor Moore then attacked USS Varuna. A long chase followed, with both ships firing. Governor Moore rammed Varuna. The cottonclad ram Stonewall Jackson also rammed Varuna. Varuna reached shallow water before sinking. She was the only Union ship lost. Lieutenant Beverly Kennon, captain of Governor Moore, wanted to keep fighting. But his steersman drove the ship ashore. Kennon realized the ship couldn't do more, so he ordered it abandoned and set on fire.

CSS McRae fought several Union ships. Her captain, Lieutenant Commander Thomas B. Huger, was badly wounded and died later. McRae was badly damaged. She survived the battle but later sank in New Orleans.

The rest of the Confederate ships did not harm the Union fleet. Most were sunk by Union fire or by their own crews. The ships that survived were McRae, CSS Jackson, ram Defiance, and transport Diana. Two unarmed support boats surrendered with the forts. Louisiana also survived the battle but was sunk by her crew to avoid capture.

In total, the Union Navy lost one ship. The Confederates lost twelve ships.

Historian John D. Winters wrote that the Confederate fleet in New Orleans "made a sorry showing." He said that self-destruction, lack of teamwork, and the strong Union fire destroyed the fleet. Historian Allan Nevins said the Confederate defenses were weak. He noted that the Confederates had tried to defend the river, but they lacked money, organization, skilled workers, and good planning.

New Orleans and the Forts Surrender

The Union fleet faced little resistance at Chalmette. Then, they had a clear path to New Orleans. The fourteen remaining Union ships arrived on the afternoon of April 25. They aimed their guns at the city. General Mansfield Lovell had already moved his troops out of the city, so no defense was possible.

Citizens in New Orleans panicked. They broke into stores, burned cotton and other supplies, and destroyed much of the waterfront. The unfinished CSS Mississippi was quickly launched. They hoped to tow her to Memphis, but no towboats were found. So, her captain ordered her burned. Farragut demanded the city surrender. The mayor and city council tried to pass the duty to Lovell, but he sent it back to them. After three days of talks, Farragut sent officers, sailors, and marines ashore. They went to the Custom House, took down the state flag, and raised the United States flag. This meant the city was officially back under Union control.

Meanwhile, General Butler was getting his soldiers ready to attack the forts behind Farragut's fleet. Commodore Porter, who was still in charge of the mortar fleet below the forts, demanded the forts surrender. General Johnson K. Duncan refused. So, Porter started bombarding the forts again, preparing for Butler's attack. However, on the night of April 29, the soldiers in Fort Jackson refused to fight anymore. They mutinied. Fort St. Philip was not part of the mutiny, but it depended on Fort Jackson. Since they couldn't continue fighting, Duncan surrendered the next day.

The CSS Louisiana was destroyed at this time. Commander John K. Mitchell, who led the Confederate Navy ships near the forts, was not part of the surrender talks. He didn't feel he had to follow the truce. So, he ordered Louisiana to be destroyed. She was set on fire, floated down the river, and blew up as she passed Fort St. Philip. The explosion was so strong it killed one soldier in the fort.

What Happened Next

Forts Jackson and St. Philip were the main defenses for the Confederacy on the lower Mississippi. With them gone, there was nothing to stop the Union from the Gulf all the way to Memphis. After repairing his ships, Farragut sent groups north to demand other cities on the river surrender. Baton Rouge and Natchez surrendered because they had no way to defend themselves.

At Vicksburg, however, the ships' guns could not reach the Confederate forts on top of the bluffs. The small army with them could not force the issue. Farragut tried to lay siege to Vicksburg, but he had to leave when the river levels dropped. This threatened to trap his large ships. Vicksburg would not fall until another year passed.

The fall of New Orleans also influenced European countries, especially Great Britain and France. It likely stopped them from officially recognizing the Confederacy as a country. Confederate agents in Europe noticed that they were treated less warmly after news of New Orleans's capture reached London and Paris.

|

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |