USS Brooklyn (1858) facts for kids

USS Brooklyn

|

|

Quick facts for kids History |

|

|---|---|

| Name | USS Brooklyn |

| Namesake | The City of Brooklyn on Long Island, later one of the five boroughs of New York City |

| Builder | Jacob A. Westervelt and Son |

| Laid down | 1857 |

| Launched | 1858 |

| Commissioned | January 26, 1859 |

| Decommissioned | May 14, 1889 at the New York Navy Yard |

| Stricken | January 6, 1890 |

| Fate | Sold March 25, 1891 at the Norfolk Navy Yard |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Brooklyn |

| Displacement | 2,532 tons |

| Length | 233 ft (71 m) (at the waterline) |

| Beam | 43 ft (13 m) |

| Draft | 16 ft 3 in (4.95 m) |

| Propulsion | steam engine screw-propelled as well as ship-rig sail |

| Speed | 11.5 knots |

| Complement | 335 officers and enlisted |

| Armament |

|

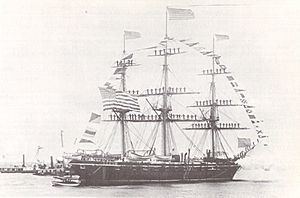

The USS Brooklyn (1858) was a powerful warship built for the U.S. Navy. It was a "sloop-of-war," meaning it was a sailing ship with a steam engine and propeller. The U.S. Congress approved its construction, and it began service in 1859.

Brooklyn first operated in the Caribbean Sea. When the American Civil War began, it played a big part in the Union blockade against the Confederate States of America. With one 10-inch gun and twenty 9-inch guns, it could fire strong broadsides. It helped stop ships along the Atlantic and Gulf Coast of the United States. Brooklyn also attacked Confederate forts and bases on the Mississippi River.

After the war, Brooklyn continued its service. It sailed in Europe and even traveled all the way around the world. The ship was retired in 1889 and sold in 1890. It had served the country for over 30 years.

Contents

Building the USS Brooklyn

Brooklyn was the first ship named after the City of Brooklyn. It was one of five similar warships approved by the U.S. Congress on March 3, 1857. The ship was built by Jacob A. Westervelt and Son. It was launched in 1858 and officially started service on January 26, 1859. Its first commander was Captain David G. Farragut.

Early Missions in the Caribbean

Helping in Haiti

On February 5, Brooklyn sailed to Beaufort, South Carolina. After a week there, it headed to the West Indies. Its mission was to check on the situation in Haiti. Liberal forces had taken control from Emperor Soulouque. They had put Fabre Geffrard in charge as President.

Captain Farragut found that the people of Haiti were happy to be free. They were glad the war had ended. Following advice from the American consul, Farragut then sailed to the Isthmus of Panama.

Protecting Americans in Mexico

After visiting Aspinwall, Brooklyn went to the Mexican coast. It arrived at Veracruz in early April. The legal president of Mexico, Benito Juárez, was using Veracruz as his temporary capital. He had been forced out of Mexico City by General Miguel Miramón.

The United States supported President Juárez. They sent Robert Milligan McLane to Veracruz as the American minister. Farragut was told to make Brooklyn available to McLane. This way, McLane could stay updated on the civil war. He could also help American citizens and their property. McLane sometimes lived on board the ship.

In July, Brooklyn went to Pensacola, Florida, for supplies. It returned to Veracruz, then back to Pensacola by September 7. From there, it sailed to New York. It reached the New York Navy Yard on September 26.

More Missions in Mexico

On November 8, Brooklyn left New York Harbor with McLane on board. McLane had been in the U.S. for meetings. The ship headed back to the Gulf of Mexico. It arrived at Veracruz on November 21. McLane worked on an agreement with the Juárez Government. After the treaty was signed on December 12, the ship sailed to New Orleans, Louisiana. It arrived there on December 18.

With full supplies, Brooklyn left New Orleans on Christmas Eve. It crossed the gulf to Veracruz. In mid-January, it took McLane back to New Orleans. He needed to catch a train to Washington, D.C. There, he had to explain the treaty to senators.

From New Orleans, Brooklyn went to Pensacola. It was getting ready to return to Mexico. But before McLane could get back, new orders arrived. The ship was sent north. It sailed on February 19, 1860, and reached New York City on February 27. On March 11, it sailed again to Norfolk, Virginia. It arrived the next day. There, it waited for McLane and took him back to Veracruz on March 28.

Surveying the Isthmus

The ship operated along the Mexican coast through the spring and summer. It carried McLane to different ports for meetings. In late July, it left Mexico and returned to Norfolk in early August. There, it received orders for a special trip. It was to carry scientists to the Gulf of Mexico. Their goal was to find a route across the Chiriqui isthmus. The ship sailed on August 13 and reached Chiriqui, Boca del Toro, Panama, on August 24. It stayed there until mid-October, except for a trip to Aspinwall. On October 20, Captain William S. Walker took command from Farragut.

Civil War Service

The Fort Sumter Attempt

Soon after, Brooklyn returned to Hampton Roads, Virginia. It stayed in the Norfolk area through late 1860. This was when many Southern states were leaving the Union after Abraham Lincoln became president. In January 1861, Captain Walker received orders. Brooklyn was to go to Charleston, South Carolina. It carried messages for the ship Star of the West. That ship was trying to resupply Fort Sumter, which was under attack. However, when Brooklyn reached Charleston Harbor, the channel was blocked. The resupply effort had failed. So, Brooklyn returned to Hampton Roads.

Blockading the Gulf of Mexico

The next month, Brooklyn had a similar mission. This time, it succeeded in helping Fort Pickens in Pensacola, Florida. After stopping Confederate attempts to take this important fort, Brooklyn sailed west. Its job was to blockade the Mississippi Passes.

Brooklyn, USS Powhatan, and two gunboats captured several ships. But many ships were still getting through. Commander Charles Henry Poor took command of Brooklyn in April 1861. He tried to go upriver to the Head of Passes to stop more traffic. But the water was too shallow, and the ship ran aground twice.

On June 30, 1861, the Confederate warship CSS Sumter sped out of Pass a l'Outre. Brooklyn had left its station to chase another ship. When Brooklyn saw Sumter, it stopped the first chase. It used full sails and steam to try and catch Sumter. But Sumter was too fast and escaped. Brooklyn needed repairs badly. It sailed north in the autumn and was taken out of service at the Philadelphia Navy Yard.

Return to Gulf Operations

Brooklyn was put back into service on December 19, 1861. Captain Thomas T. Craven was now in command. The ship sailed down the Delaware River on December 27 and headed for the gulf. After stopping at Key West, Florida, it reached Ship Island, Mississippi, on January 22, 1862. On February 2, it sailed to Pass a l'Outre. There, on February 19, it captured the steamer Magnolia. This ship was trying to leave with 1,200 bales of cotton.

Meanwhile, the Navy had split its forces in the gulf. Flag Officer William W. McKean led the East Gulf Blockading Squadron. Flag Officer David G. Farragut led the West Gulf Blockading Squadron. Farragut arrived at Ship Island in March. Besides blockading, Farragut was ordered to lead a fleet up the Mississippi River to capture New Orleans.

Farragut spent late March and early April getting his large ships over the sandbar and into the river. He then moved his fleet up the Mississippi. They stopped just out of range of the guns at Confederate Forts Jackson and St. Philip.

Attacking Forts St. Philip and Jackson

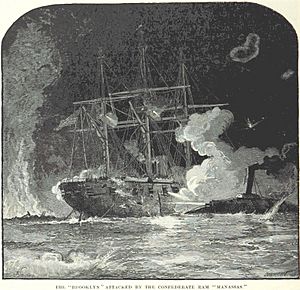

A group of small sailing ships with 13-inch mortars joined Farragut's force. In mid-April, these ships began bombing the Southern forts. They continued until early April 24. Then, they fired even faster. Farragut's large warships began their dash past the Southern guns. Brooklyn was:

- "... hit several times before it could fire its guns. As soon as we could, we opened fire on Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip. We fought both batteries at times. One of our gunboats hit us, but we were not damaged. The ram Manassas tried to sink us by crashing into us, but it did little harm. A fire raft came down the river towards us, but we crossed it safely. We almost got stuck on some old ships and log rafts. This kept us under fire longer than we should have been."

Eight men from Brooklyn were killed in this battle. Twenty-one were wounded. This happened before the ship reached safety beyond the range of the Confederate cannons. Later that day, after repairs, Farragut's warships continued upriver. They reached New Orleans on April 25. After the city surrendered, Brooklyn received a large patch on its hull. It had been damaged more by the collision with Manassas than first thought. One of Brooklyn's sailors, Quartermaster James Buck, received the Medal of Honor for his bravery in the battle.

Capturing New Orleans

Farragut's orders were to clear the Mississippi River of all Confederate forces. He was to move upstream until he met another Union squadron. This squadron, led by Flag Officer Charles Henry Davis, was fighting its way downriver from Cairo, Illinois. So, in early May, after Union Army troops arrived and took over New Orleans, Brooklyn and six other warships went up the river.

Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and Natchez, Mississippi, surrendered without a fight. But Vicksburg, Mississippi, was different. The Confederate Army had heavily fortified its riverside hills. It could not be taken without a strong land force. The Union Army did not have enough troops there. So, Farragut's warships returned to New Orleans.

The Attack on Vicksburg

Orders from Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles were waiting for him. They repeated how important it was to meet Davis's force above Vicksburg. So, the Union warships turned around again. They slowly moved upstream to a spot just out of range of Vicksburg's guns. This time, they had help from the Mortar Flotilla. This group heavily bombed the fortress first. At 2:00 AM on June 28, the fleet started moving upstream in two lines.

Unfortunately, the steamers that towed the mortar schooners got in the way of Brooklyn and two gunboats. This stopped them from getting past the Vicksburg batteries. As a result, they took a lot of Confederate fire. Farragut's other ships pushed upstream and out of range. Shortly before dawn, Brooklyn moved downstream to a safer place. It stayed there to support Farragut if needed. As the hot summer passed, more sailors got sick. The river's water level also dropped. This made it necessary for the ship to move further downstream towards New Orleans.

On July 2, Captain Henry H. Bell took command of Brooklyn from Captain Craven. On August 6, the ship fought Confederate batteries at Donaldsonville, Louisiana. It drove the Southern artillerymen from their guns. On August 9 and 10, it helped in combined operations. These partly destroyed Donaldsonville as punishment for guerrilla attacks on Union ships from that town.

Temporary East Coast Duty

Soon after, Brooklyn left the Mississippi. It steamed to Pensacola for more lasting repairs. These were for the damage it got fighting past Forts Jackson and St. Philip and hitting Manassas. On October 6, orders sent the ship to blockade duty off Mobile Bay. It spent the rest of 1862 there. It watched for blockade runners and Confederate cruisers that might threaten Union gunboats.

Action in the Gulf of Mexico

In early January 1863, Farragut heard that a surprise Confederate attack at Galveston, Texas, had recaptured that port. This broke the blockade there. He put Bell in charge of a small force to regain Union control. Shallow water stopped Brooklyn from bombing Confederate gun positions in Galveston harbor on January 10. On the night of January 11, CSS Alabama sank Brooklyn's strong partner, the sidewheel steamer USS Hatteras. This happened in a fierce but quick fight about 30 miles off Galveston. This setback made Bell give up his plan to retake the port. He waited for powerful, shallow-draft reinforcements. Brooklyn continued to blockade Galveston into the summer.

On May 25, Bell left Commander James Robert Madison Mullany in the USS Bienville in charge of the Galveston blockade. He then went down the Texas coast to the Rio Grande. He wanted to find out about the local coastal trade.

On May 27, Brooklyn captured the 17-ton sloop Blazer. It was carrying cotton and heading for Matamoros, Mexico. The next day, boats from Brooklyn took the small sloop Kate. Three days later, it anchored off the bar outside Brazos Santiago, Texas. It sent "an expedition of four boats and 87 men to capture vessels there."

As the Union boats neared Point Isabel, the Confederates "set fire to a large schooner." The Union forces brought out the 100-ton schooner Star and a fishing boat. At Point Isabel, they captured the 100-ton British sloop Victoria of Jamaica. But they ran that ship aground while trying to get to sea, so they burned it. After the landing parties returned to the ship, Brooklyn went back to Galveston.

In late July, it returned to New Orleans. On August 2, Lt. Comdr. Chester Hatfield took command from Bell. This freed Bell to temporarily command the West Gulf Blockading Squadron. Farragut had gone home for a well-deserved leave. On August 10, Captain George F. Emmons relieved Hatfield. He sailed Brooklyn north on August 13 for much-needed repairs. It left the Southwest Pass the next day. It stopped at Port Royal, South Carolina, on August 21, and at Charleston, South Carolina, on August 22. It reached the New York Navy Yard on August 25.

The Battle of Mobile Bay

Brooklyn was put back into service on April 14, 1864. It sailed on May 10 under Captain James Alden, Jr.. It rejoined its squadron off Mobile Bay on May 31. Farragut, who was back in command, wanted to capture this important port. But he was held up by a lack of Union Army troops. These troops were needed for the planned joint operation. He also waited for monitors to arrive to strengthen the squadron. Brooklyn helped blockade Mobile Bay while Farragut waited. Finally, in late July, it and its squadron mates received orders to get ready for the attack.

On the morning of August 5, Farragut took his squadron of 18 ships. This included four monitors. They went against the strong Confederate defenses of Mobile Bay. Soon after 6:00 AM, the Union ships crossed the bar and moved into the bay. The four monitors formed a line to the starboard of the wooden ships. This was so they could take most of the fire from Fort Morgan. They had to pass this fort very closely. Brooklyn led the second line. This line had seven smaller wooden ships tied to the port side of the larger wooden screw steamers. This was similar to how they passed Fort Hudson.

Shortly before 7:00 AM, Tecumseh fired on Fort Morgan. The battle quickly became widespread. As the four Confederate ships fought the attackers, a huge explosion shook the Union monitor USS Tecumseh. It tilted violently and sank in seconds. It was hit by one of the feared torpedoes (naval mines). These had been laid by the Confederates for harbor defense.

Alden, on Brooklyn, was to Tecumseh's left when the disaster happened. The large steamer stopped and began backing up. It wanted to clear "a row of suspicious-looking buoys" directly under Brooklyn's front. The entire line of wooden ships was getting confused. They were right under the guns of Fort Morgan. Farragut, tied in the rigging to see over the smoke, acted quickly. The only brave choice was to go through the torpedo field. "D***n the torpedoes," he ordered, "full speed ahead." His flagship Hartford swept past Brooklyn into the rows of torpedoes. The rest of the fleet followed. The Union force steamed into the bay.

In the battle that followed, the ironclad CSS Tennessee tried to ram Brooklyn, but failed. The Union fleet defeated three of the Confederate ships. This left Tennessee as the only defender. The lone ironclad then fought the entire Union fleet. After a fierce battle lasting over an hour, Tennessee was forced to surrender. This resulted in a Union victory.

During the battle, which lasted a little over three hours, Brooklyn had 54 casualties. This included 11 killed and 43 wounded. It fired 183 projectiles. Twenty-three of Brooklyn's sailors and marines received the Medal of Honor for their part in the battle. Their names were:

|

|

Attacking Fort Fisher

After helping to reduce the Confederate land defenses, Brooklyn left Mobile Bay on September 6. It headed for Hampton Roads to join the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Soon after, Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter gathered his warships. They were preparing for a joint Army-Navy operation against Fort Fisher, North Carolina. This fort guarded the entrance to Wilmington, North Carolina. Wilmington was the last major Confederate port still open for blockade runners. Brooklyn took part in the attack. It began with a bombardment on Christmas Eve. It helped cover the landing of troops the next day. But the whole effort failed. The Union Army commander, Major General Benjamin F. Butler, decided his forces could not take the Confederate defenses. He ordered his soldiers to re-embark.

Porter strongly disagreed with this decision. General Ulysses S. Grant responded by putting a new commander in charge of a larger Army force. This force was for another attempt to take Fort Fisher. Brooklyn was in the task force that arrived off Fort Fisher on January 13, 1865. Its guns supported the attack until the fort surrendered on January 15. This victory completed the last major task of the Union Navy during the Civil War. Brooklyn sailed north and was taken out of service at the New York Navy Yard on January 31, 1865.

Post-War Service

South Atlantic Operations

The ship was under repair for the rest of the war. It was put back into service on October 4, 1865. Commander Thomas H. Patterson was in command. It sailed on October 27 and went via the Gulf of Mexico to Bahia, Brazil. After almost two years of service along the Atlantic coast of South America, it returned to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in late summer 1867. It was taken out of service there on September 11.

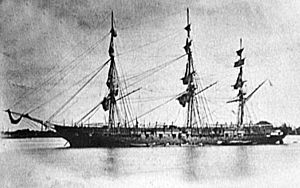

Extended European Tour

Brooklyn was put back into service on August 24, 1870. Captain John Guest was in command. It sailed east across the Atlantic. It spent almost three years in European waters, mostly in the Mediterranean. After returning home in summer 1873, it was taken out of service in New York City.

Flagship in the South Atlantic

The veteran warship was reactivated on January 20, 1874. It operated along the southern coast of the United States until autumn. Then, it entered the Norfolk Navy Yard. It was being prepared to serve as the flagship for the South Atlantic Squadron. It sailed for the coast of Brazil on January 23, 1875. It operated in South American waters, protecting American interests. It headed home on December 7. After serving in the Home Squadron, it was taken out of service in New York City on July 21, 1876.

Brooklyn was put back into service on November 11, 1881. It sailed on December 7 for Montevideo, Uruguay. This was for another tour of duty with the South Atlantic Squadron. On February 5, 1882, it left that port and headed for the Strait of Magellan. During that month, it visited several places like Possession Bay and Elizabeth Island. It left Possession Bay on March 2, 1882, and returned via Stanley, Falkland Islands, to Montevideo in late March.

While operating from Montevideo for the next 18 months, it made two trips to Santa Cruz, Patagonia. It also made one trip to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Then, on September 28, 1883, it sailed for Cape Town, Africa. During its time in African waters, it visited places like Tomatave, Madagascar; Zanzibar; and Port Elizabeth, Africa. It left Cape Town on March 13, 1884. It proceeded homeward via St. Helena Island, Montevideo, and Rio de Janeiro. It arrived in New York City on October 8, 1884, and was taken out of service there on October 25.

After almost a year of rest, Brooklyn was put back into service on October 15, 1885. On November 21, it was assigned again to the South Atlantic Squadron. It served in South American waters until heading home on June 9, 1886.

Sailing Around the World

In New York, it prepared for duty in the Far East. On August 12, it sailed for the Far East. It crossed the Atlantic and the Mediterranean. Then, it went through the Suez Canal. It traveled through the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean to East Asian waters.

On April 4, 1887, Rear Admiral Chandler moved his flag to Brooklyn. He was the commander of the Asiatic Squadron. The ship represented the U.S. in ports of the western Pacific Ocean. It turned homeward for the last time on August 9, 1888. It returned to the United States via Honolulu; Cape Horn; and St. Thomas. Brooklyn completed its first circumnavigation (sailing around the earth) when it arrived in New York on April 24, 1889. This also marked the end of its active naval career.

Final Retirement and Sale

The ship was taken out of service at the New York Navy Yard on May 14, 1889. Its name was removed from the Navy List on January 6, 1890. It was sold by public auction at the Norfolk Navy Yard on March 25, 1891, to E. J. Butler.

Images for kids

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |