River Defense Fleet facts for kids

Quick facts for kids River Defense FleetConfederate State of America |

|

|---|---|

| Active | March to June 1862 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Engagements | Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip Battle of Plum Point Bend Battle of Memphis |

The River Defense Fleet was a group of fourteen ships used by the Confederate States during the American Civil War. Their main job was to help protect New Orleans and other parts of the Mississippi River. These ships were originally regular merchant ships or towboats. The Confederate War Department took them over and turned them into warships.

Each ship was given one or two guns. Their engines were protected by a strong wall inside the ship. Their front ends (bows) were made extra strong so they could be used to ram enemy ships. Even though they were part of the Confederate States Army, most of their leaders and crew were civilians, not military officers. Some of the fleet stayed in the southern part of the Mississippi River. The rest were sent north to fight against Union forces moving down the river.

The southern part of the fleet fought in the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip. The northern part fought in the battles at Plum Point Bend and Memphis. These ships were only successful under very specific conditions. If those conditions weren't met, they were usually defeated. By the middle of 1862, the entire fleet was gone. They were either destroyed by enemy action or sunk by their own crews.

Contents

How the River Defense Fleet Started

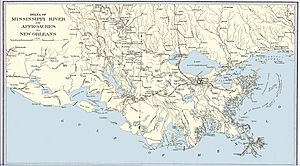

When the Civil War began in April 1861, the Confederate states faced a problem. President Abraham Lincoln announced a blockade, meaning Union ships would stop goods from entering or leaving Confederate ports. Also, Union General Winfield Scott had a plan called the Anaconda Plan. This plan suggested moving down the Mississippi River to capture New Orleans.

Even though the Anaconda Plan wasn't fully used, it reminded Confederate President Jefferson Davis how important the Mississippi River was. Many people suggested ways to defend it. Among these ideas was one from two riverboat captains, James E. Montgomery and J. H. Townsend.

The captains suggested using fast, large ships and turning them into rams. They would strengthen the front of the ships with railroad iron. The ships' engines would be protected by strong inner walls. They would only have one or two guns, as their main weapon would be ramming slow enemy gunboats. Montgomery and Townsend would choose experienced river captains from New Orleans. Each captain would then hire their own crew.

Montgomery and Townsend didn't go through the usual War or Navy Departments. Instead, they got support from all the Mississippi representatives in the Confederate Congress. They also got support from Major General Leonidas Polk, a friend of President Davis. This political approach worked. Congress approved their plan and gave them $1,000,000 even before Townsend returned to New Orleans to start the ship changes.

Turning Merchant Ships into Warships

After the plan was approved, Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin sent a message to Major General Mansfield Lovell. Lovell was in charge of the military area that included New Orleans. He was told to take fourteen steamboats for war use. This was Lovell's first involvement with the River Defense Fleet. He quickly became a strong critic of it. He worried about how disorganized the fleet would be. He famously said, "Fourteen Mississippi River captains and pilots will never agree about anything once they get underway." Still, he followed orders and took possession of fourteen steamers. Some ships were swapped out, but the fleet still ended up with fourteen vessels.

Each ship was changed to be a ram. Their bows (fronts) were filled with solid oak wood. The front 20 feet (6.1 meters) were covered with oak planks and then with 1-inch (25-millimeter) thick railroad iron. The engines were protected by two walls. The inner wall was made of 12-inch (30-centimeter) pine beams. The outer wall used 6-inch by 12-inch (15-centimeter by 30-centimeter) beams. This outer wall was also covered with 1-inch (25-millimeter) thick railroad iron. The space between the two walls, 22 inches (56 centimeters), was filled with packed cotton. Even though the cotton wasn't the most important part of the armor, people liked the idea. These ships became known as "cottonclads."

The "cottonclad" ships were finished between March 16 and April 17, 1862. This was exactly when the Union fleet, led by Flag Officer David Farragut, was gathering in the lower river. They were getting ready to attack New Orleans. The finished rams were supposed to go upriver to help defend Island Number 10 and Memphis. However, General Lovell convinced the War Department to let him keep the first six ships near New Orleans.

These six ships were the Stonewall Jackson, Warrior, Defiance, Resolute, General Breckinridge, and General Lovell. Captain Townsend was no longer with the fleet. Captain Montgomery went with the northern group of ships. Another riverboat captain, John A. Stephenson, was chosen to lead the six New Orleans ships.

The other eight ships were sent to Memphis. They were the General Bragg, General Sterling Price, General Earl Van Dorn, Colonel Lovell, General Beauregard, General M. Jeff Thompson, Little Rebel, and General Sumter. The last ship was finished on April 17, the day before the attack on Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip began.

Because these ships were mainly meant to ram, they had very few guns, usually just one or two. Also, their captains didn't spend much time practicing with the guns. This caused another problem: Army artillery soldiers were assigned to work the guns, but they still took orders from Army officers, not the ship captains.

The River Defense Fleet in Battle

Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip

Near New Orleans, three different Confederate groups were operating on the Mississippi River. There was the Confederate States Navy, the Louisiana state navy, and the River Defense Fleet. On April 20, 1862, after the attack on Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip had started, General Mansfield Lovell tried to make things clearer. He ordered that all ships would now take orders from Commander John K. Mitchell of the Confederate Navy.

However, Captain John A. Stephenson of the River Defense Fleet refused this order. He said that everyone in the River Defense Fleet joined on the condition that they would be independent of the Navy. This act of refusal couldn't be punished because of the fleet's unusual connection to the Army.

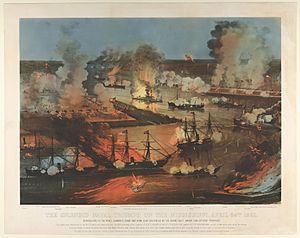

On the night of April 24, David Farragut's Union fleet sailed past the Mississippi River forts that protected New Orleans. The Confederate leaders had not planned well between the forts and the ships. So, the battle was split into two separate parts. Each attacking Union ship passed the forts first. Then, they faced the Confederate ships, which received all the Union gunners' attention.

Under these conditions, only one River Defense Fleet ship managed to get close to an enemy. The Stonewall Jackson rammed the USS Varuna. At the same time, the Varuna was also being rammed by the Governor Moore from the Louisiana navy. The Varuna sank, becoming the only Union ship lost that night. However, the Stonewall Jackson was also badly damaged. Hit by shots from other Union ships, her crew ran her ashore, abandoned her, and set her on fire.

Of the other five ships in the fleet, one (Warrior) was destroyed by shots from the USS Brooklyn. The Resolute was run ashore and abandoned by her crew. Ten men from another Confederate ship tried to save her but couldn't, so they burned her. The General Breckinridge and General Lovell were also abandoned and burned by their crews. Only the Defiance escaped unharmed. She fled to New Orleans, where her crew left her. Her captain then turned her over to Commander Mitchell. Mitchell had no other choice but to order her burned when the city fell to the Union.

The Battle of Plum Point Bend

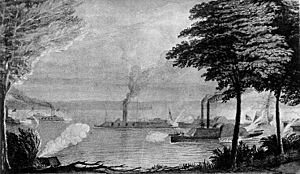

Even though the New Orleans part of the River Defense Fleet was destroyed, the eight ships in the northern section had a chance to get back at the Union. On May 10, 1862, they surprised the Union Western Gunboat Flotilla near Plum Point Bend on the Mississippi. This was about 40 miles (64 kilometers) north of Memphis.

The Union fleet was spread out. One gunboat and a mortar raft were in an exposed spot, far from the other gunboats. Even though the Union knew the Confederate ram fleet was nearby, they didn't send out scout boats. So, they had no warning until they saw smoke from the enemy fleet over the trees at Plum Point.

Caught off guard, the Union gunboats started their engines and entered the battle one by one. This allowed the Confederate rams to focus on each Union ship as it arrived. The USS Cincinnati and Mound City were hit multiple times and had to be run aground in shallow water to keep them from sinking. By this time, the other Union gunboats had gotten ready and were joining the fight. So, Captain Montgomery pulled his fleet back. They escaped with only minor damage.

It's hard to say how big a victory this was for the Confederates. While disabling two gunboats was a good achievement, neither was lost for long. Within a few weeks, both were raised, repaired, and back in service. So, at best, the fleet only delayed the Union's plans for a short time.

The Battle of Memphis

Less than a month after the fight at Plum Point, the River Defense Fleet fought the Western Gunboat Flotilla again. But the conditions were very different. One change might have greatly affected the battle. The fleet had a strange command system where Army artillerymen operated the guns but weren't part of the ship crews. This system broke down as Confederate losses grew, hurting morale. The gunners and rivermen disagreed more and more. At one point, the soldiers refused to go with the fleet on a small mission. Finally, on June 5, 1862, Brigadier General M. Jeff Thompson removed his men. This would have been a serious problem if the rams relied heavily on their guns. As it was, the soldiers leaving only slightly affected the fleet, though it certainly didn't help.

The very next morning, June 6, the Union fleet was united and ready to fight. They were also joined by two Union rams from the United States Ram Fleet. This Union ram fleet was similar to the Confederate force, even having some of its own organization problems. The Confederate fleet had little choice but to fight at Memphis. However, they didn't have more ships than the enemy, like they did at Plum Point.

The battle was a confusing fight. This was mostly because the unclear command structures on both sides led to many uncoordinated clashes between rams. The Confederate rams also faced heavy gunfire from the Union fleet. While exact details are hard to confirm, the outcome was clear: one Union ram was sunk (but later recovered), while seven of the eight Confederate ships were either sunk or captured by the Union. Only the General Earl Van Dorn escaped. She fled up the Yazoo River to safety, but was accidentally burned on June 26.

Images for kids

-

{Ex CSS} USS General Bragg probably photographed at Cairo or Mound City, Illinois, around 1862–63. -

{Ex CSS} USS General Price off Baton Rouge, LA, January 18, 1864

What We Learned

The River Defense Fleet ended early in the war. This allowed people who worked with it to think about how it performed. General Mansfield Lovell was one of the strongest critics. While his comments were about the six ships near New Orleans, they can apply to the whole fleet: "Unable to govern themselves, and unwilling to be governed by others, their almost total want of system, vigilance, and discipline rendered them nearly useless and helpless."

Beyond just these fourteen ships, the end of the River Defense Fleet, along with the end of privateering (private ships attacking enemy shipping), showed something important. It marked the end of naval warfare carried out by people who weren't professional sailors. Warships became very different from merchant ships. This meant that warships needed to be commanded and mostly crewed by people who dedicated their lives to being sailors. Since the Civil War, no major country has thought about using private fleets for war, no matter the situation.

See also

In Spanish: Flota de Defensa Fluvial para niños

In Spanish: Flota de Defensa Fluvial para niños