First Battle of Charleston Harbor facts for kids

Quick facts for kids First Battle of Charleston Harbor |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Advance of Ironclads to the Attack, April 7th, 1863 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| South Atlantic Blockading Squadron | First Military District of South Carolina | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2 ironclads 7 monitors |

2 ironclads 385 land-based guns |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1 killed 21 wounded 1 ship sunk |

5 killed 8 wounded |

||||||

The First Battle of Charleston Harbor happened on April 7, 1863, during the American Civil War. It was a fight near Charleston, South Carolina. The main attackers were nine powerful armored ships, called ironclads, from the Union Navy. Seven of these were 'monitors,' which were improved versions of the famous USS Monitor. The Union Army was also nearby, but they didn't join the actual battle.

Rear Admiral Samuel Francis Du Pont led the Union ships. They attacked the Confederate forts protecting Charleston Harbor. Leaders in Washington hoped this battle would prove that these new armored ships with big guns could defeat old-style forts.

Du Pont's fleet included the strong New Ironsides, the experimental Keokuk, and seven Passaic-class monitors. Other naval operations were put on hold to send ships to Charleston. After a long wait, the weather and tides were finally right for the attack.

The slow monitors took a long time to get into position. When the tide changed, Du Pont had to stop the attack. The fighting lasted less than two hours. The Union ships couldn't get past the first line of Confederate defenses. One Union ship was sinking, and most others were damaged. One Union sailor died, and 21 were hurt. Five Confederate soldiers died, and eight were wounded. After talking with his captains, Du Pont decided his fleet couldn't win. So, he didn't restart the battle the next morning.

Contents

Why Charleston?

Union's Goals

In late 1862 and early 1863, the war wasn't going well for the Union. The Confederate Army of Northern Virginia had escaped after the Battle of Antietam. They had also badly beaten the Union Army of the Potomac at Fredericksburg, Virginia. In the West, the fight for the Mississippi River was stuck at Vicksburg, Mississippi. The Confederates even took back Galveston, Texas.

Many people in the North were tired of the war. Recent elections showed less support for the Republican party. So, President Abraham Lincoln's government pushed its commanders for a victory. They needed something to boost the country's spirits. This is why the Navy Department pushed for an attack on Charleston.

Charleston wasn't super important for military reasons in 1863. Other ports like Mobile or Savannah were just as useful for blockade runners. Wilmington, North Carolina, was even more important. But Charleston was chosen because it was a symbol. It was where the war had started when Confederates fired on Fort Sumter. Many people saw Fort Sumter as the heart of the rebellion.

Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus Vasa Fox strongly supported the attack. He also wanted the Navy to be seen as strong and independent from the Army. So, he didn't mind when General-in-Chief Henry Halleck didn't want the Army to play a big role. Halleck only offered 10,000 to 15,000 untrained soldiers. They would only help if the Navy succeeded, not actively fight.

The Navy Department sent almost all its armored ships to the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Rear Admiral Du Pont commanded this squadron. His main ship was the huge USS New Ironsides. Seven Passaic-class gunboats, which were improved versions of the original USS Monitor, also joined. The experimental armored gunboat Keokuk was also part of the fleet.

Du Pont wasn't as excited about these armored ships as the Navy Department. He knew they could take a lot of hits from shore guns. But their own attacking power was limited. New Ironsides had 16 guns, but only 8 could fire at once. The other ships had only two guns each. Each Passaic had one 15-inch and one 11-inch gun. Keokuk had two 11-inch guns. These guns were bigger than the typical 32-pounders the Confederates used. But they fired much slower. It took seven minutes to clean, reload, and aim between shots.

Du Pont didn't suggest other ways to capture Charleston. He focused on keeping his ships safe. His doubts about the mission are important when looking at the battle's outcome.

Confederate Defenses

General P. G. T. Beauregard was in charge of the Confederate forces in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. He had led the Confederate forces at Charleston when the war began at Fort Sumter. So, he knew the city's defenses very well. He had been away but returned in September 1862. The batteries he had set up to attack Fort Sumter were now part of the harbor defenses. His replacements had added some things, but Beauregard designed most of it.

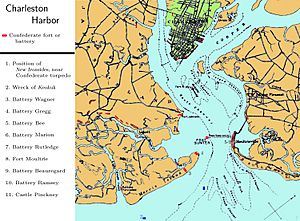

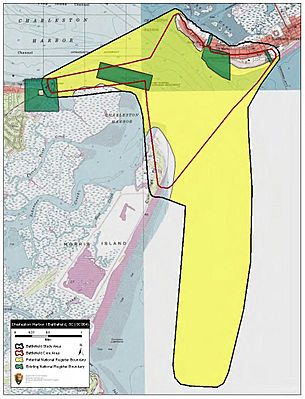

The forts around the harbor were very good at stopping attacks from the sea. The furthest guns were at Battery Wagner and Battery Gregg on Morris Island. Nearby, on a man-made island, was Fort Sumter. Fort Moultrie and its batteries were across the harbor on Sullivan's Island. These made up the first line of defense.

A second line included Fort Johnson and Battery Glover on James Island. Also, Fort Ripley and Castle Pinckney in the harbor, and the White Point Battery (Battery Ramsay) at the city's southern end. A third line of batteries protected against land attacks on the city. In total, the Confederates had about 385 land-based guns.

The Confederates also had barriers in the harbor. First, they tried a row of piles from Fort Johnson to Fort Ripley. But storms and strong tides broke it apart. Later, a "boom" was placed between Forts Sumter and Moultrie. This was made of 20-foot railroad iron pieces, floated by timbers, chained together, and anchored. This barrier also broke due to the tides. They added a rope barrier to tangle enemy ship propellers. Even with all this effort, the defenders didn't think these barriers would stop an invading fleet. The same was true for most of the torpedoes (which were like modern-day mines) they had placed. Du Pont didn't know these barriers were weak. So, he worried a lot about them during his preparations.

The South also had two armored gunboats, CSS Chicora and Palmetto State. They were ready to fight if the Union ships got close to the city. But they were slow and not a big threat to the Union monitors.

The defenses around Charleston were strong. Beauregard knew he had to be ready for the worst. He decided to defend the city street by street if needed. He wrote to Governor Francis W. Pickens, saying, "As I understand it is the wish of all, people and government, that the city shall be defended to the last extremity."

The Battle Begins

Du Pont chose to attack in early April. He wanted to use the strong tides that came with the full Moon.

Dealing with Mines

As the attack date neared, the Navy Department introduced a new device. Du Pont was very worried about torpedoes (mines) in the harbor. So, the department asked John Ericsson, who designed the monitors, for a solution. He created a raft-like structure made of heavy wood. It could be attached to a ship's front. Each raft had hooks to snag the ropes of enemy torpedoes. It also carried its own torpedo to blast through barriers.

Two of these rafts were built and sent to South Carolina. Du Pont's captains worried about how the rafts would affect steering. They also worried about collisions in the narrow channel. Only one captain, John Rodgers of Weehawken, agreed to use the raft. He used it without its torpedo. But the raft hit his ship so hard that Rodgers cut it loose before it cleared any torpedoes.

Final Preparations

The Union fleet gathered outside the harbor on April 5. That day, Du Pont sent the buoy schooner USS Admiral Du Pont and the survey vessel Bibb. They were joined by Keokuk to mark the entrance channel with buoys. The next day was hazy, making it hard to navigate. So, Du Pont waited another day. The harbor was hazy again on the morning of April 7. But it cleared up by noon, and the signal to attack was given.

The Attack Line

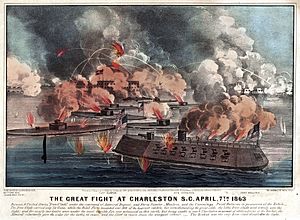

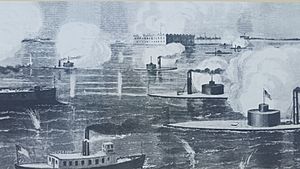

Four monitors led the way. First was USS Weehawken, led by Captain John Rodgers. As it started, Weehawken's anchor got caught on the torpedo raft's hooks. This delayed the start by about an hour. The ship could only go three knots (5.5 km/h). The rest of the ships had to follow at this slow speed.

Second was Passaic, commanded by Captain Percival Drayton, who was from Charleston. Third was Montauk, led by Commander John L. Worden. Worden was famous for commanding USS Monitor against CSS Virginia at the Battle of Hampton Roads. Next came Patapsco, under Commander Daniel Ammen.

Then came the flagship, New Ironsides, commanded by Commodore Thomas Turner. Rear Admiral Du Pont and his fleet captain, Christopher Raymond Perry Rodgers, were also aboard. After them were three more monitors: Catskill, under Commander George W. Rodgers; Nantucket, under Commander Donald M. Fairfax; and Nahant, under Commander John Downes. The experimental ironclad Keokuk, commanded by Commander Alexander C. Rhind, was at the end of the line.

Almost two hours passed from when the ships started moving until the first shots were fired. During this time, they found that New Ironsides was hard to control in the strong current and shallow water. She had to stop and anchor to avoid running aground. This happened just as the lead monitors were starting to get fired upon. She dropped out of the line, and the four ships behind her had to go around her.

The waiting Confederates couldn't have picked a better spot for New Ironsides to anchor. She was directly over a 3000-pound (1360 kg) electrically triggered torpedo. It was supposed to explode when a switch on shore was closed. But nothing happened. Some say an ordnance wagon broke the wires by driving over them. Others say the wires were too long, so the electric current wasn't strong enough.

Meanwhile, the other ships were getting hit hard. Weehawken reached a line of buoys that Captain Rodgers thought might mark torpedoes. So, he swerved from the channel and stopped. At this point, an underwater explosion shook the ship. Rodgers thought it was a torpedo, but some historians believe it was a shell from a fort. Either way, the ship wasn't badly damaged. But because she left the channel, the line of ships behind her got confused. Du Pont's battle plan fell apart.

The forts fired intensely, keeping the Union ships farther from Fort Sumter than planned. So, their return fire was less accurate. But accuracy wasn't the main problem; it was the huge difference in how many shots were fired. In two hours, the Confederates fired over 2000 shots and shells, hitting 520 times. The Union fleet fired only 154 shots. Their armor protected the crews, but several ships were damaged. Some had jammed turrets or gunport stoppers.

Keokuk was hit the worst, 90 times, with 19 hits at or below the waterline. Captain Rhind pulled his ship out of the fight. He barely kept her afloat until she was out of enemy range. By this time, the tide had turned. So, Admiral Du Pont decided to stop the attack until the next day.

End of the Battle

Du Pont said in his report that he planned to attack again the next day. But his captains all disagreed. Keokuk sank during the night (no one died). Two or three monitors were so damaged they couldn't fight for days or weeks. The captains agreed that continuing the battle wouldn't help. Even if they could destroy Fort Sumter, many other forts remained. The fleet hadn't even gotten past the first line of defense.

So, the battle ended. The Union lost one ironclad. Fort Sumter was damaged, but it could be repaired quickly. Few people were hurt despite all the firing. Only one Union sailor, Quartermaster Edward Cobb of Nahant, was killed. 21 others were injured. The Confederates lost five killed and eight wounded.

Aftermath

Secretary of the Navy Welles was upset by the failure. The low number of casualties, plus Du Pont's doubts before the battle, made Welles think the attack wasn't pushed hard enough. His criticism lessened only when John Rodgers, a respected and aggressive officer, agreed with Du Pont. Rodgers and Welles eventually agreed that Charleston couldn't be taken by just the Navy. It needed a combined effort with both the Army and Navy working together.

Welles saw that Du Pont was right about Charleston needing both Army and Navy forces. But the trust between the two men was broken. Welles removed Du Pont from command on June 3. He was replaced first by Rear Admiral Andrew H. Foote. However, Foote died before he could take command, from a wound he got during the Battle of Fort Donelson. So, Welles reluctantly gave command of the naval campaign to Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren.

Du Pont's captains did better than he did. None of them suffered professionally for their part in the failed campaign. Seven of them (John and C. R. P. Rodgers, Ammen, Fairfax, Turner, Worden, and Rhind) eventually became rear admirals. Drayton was chosen to be Chief of the Bureau of Navigation, which would have made him a rear admiral. But he died of a heart attack while waiting for Senate approval. George W. Rodgers was known as one of the best captains in the fleet, but he was killed in a later attack on Charleston.

The monitors and New Ironsides continued to help with the blockade of Charleston. But the Confederates never feared them as much after this attack. All the ships were used in the ongoing campaign against the city.

Even the sunken Keokuk played a role later. She sank in shallow water, so her smokestack was still above the surface. Her position was known. Adolphus W. LaCoste, a civilian hired by the Confederate government, was able to salvage the two 11-inch guns from the wreck. He and his crew worked at night and avoided being seen by the Union ships. Du Pont didn't know about their activity until it was announced in the Charleston Mercury.

Images for kids