Francis S. Bartow facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Francis S. Bartow

|

|

|---|---|

Bartow in c. 1960.

|

|

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Francis Stebbins Bartow

September 6, 1816 Chatham County, Georgia |

| Died | July 21, 1861 (aged 44) Manassas, Virginia |

| Resting place | Laurel Grove Cemetery, Savannah, Georgia |

| Nationality | American |

| Spouse |

Louisa Greene Berrien

(m. 1844) |

| Alma mater | Franklin College Yale Law School |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1861 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Francis S. Bartow (born Francis Stebbins Bartow; September 6, 1816 – July 21, 1861) was a lawyer who became a politician. He served in the United States House of Representatives and became an important leader of the Confederate States of America. Bartow was also a Colonel in the Georgia Militia. He commanded the 21st Oglethorpe Light Infantry during the early part of the American Civil War.

Bartow was a representative from Georgia to the Southern Convention in Montgomery, Alabama. He became one of the first members of the Confederate Provisional Congress. He helped prepare local military groups after states started leaving the Union. This led to the American Civil War from 1861 to 1865.

Colonel Bartow was killed at the First Battle of Manassas. He was the first brigade commander in the Confederate States Army to die in battle.

Contents

Early Life and Career of Francis Bartow

Francis Bartow was born on September 6, 1816, in Chatham County, Georgia. This was near Savannah, which used to be Georgia's capital. His parents were Dr. Theodosius Bartow and Frances Lloyd (Stebbins) Bartow.

Education and Law Career

He studied law at the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences in Athens. This college is part of the University of Georgia. While there, Bartow was part of the Phi Kappa Literary Society. He was also guided by John M. Berrien, who was a U.S. senator and a former Attorney General.

Bartow graduated in 1835 when he was 19. He then worked as a trainee at the law office of Berrien & Law in Savannah. He continued his studies at Yale Law School in Connecticut. In 1837, he returned to Savannah and was allowed to practice law in Georgia. He joined a law firm called Law & Lovell and became a partner. Bartow became known for his skill in handling difficult criminal cases.

Political Beginnings and Military Service

In 1840, when he was 24, Bartow supported William Henry Harrison for President. Harrison was a candidate for the Whig Party. In 1841, Bartow started his own political career. He served two terms in the Georgia House of Representatives. After that, he served one term in the Georgia Senate.

In 1844, Bartow married Louisa Greene Berrien. She was the daughter of John Berrien, who had been one of his mentors. In 1856, Bartow tried to become a member of the U.S. Congress but did not win. The next year, he was chosen as Captain of Savannah's 21st Oglethorpe Light Infantry. This was a local military company formed in 1856. He trained the volunteers, many of whom were young men from important local families.

As disagreements about slavery grew stronger across the country, Bartow worried about Georgia's future if war happened. In 1860, after Abraham Lincoln was elected, Bartow supported the idea of states having the right to leave the Union.

American Civil War Involvement

Secession and Fort Pulaski

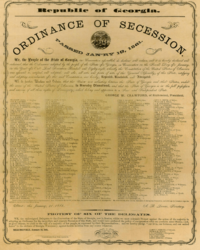

| Ordinance of Secession | |

A copy of the 1861 Ordinance of Secession. Bartow and 292 other delegates signed it at the statehouse in Milledgeville, Georgia on January 21, 1861.

|

The Georgia General Assembly called for a meeting in Milledgeville to discuss leaving the Union. This Secession Convention began on January 16, 1861. Bartow was chosen as a delegate for Chatham County.

On May 28, 1861, elections were held to pick representatives for the convention. Bartow became a delegate. However, he was on military duty that day. Governor Joseph E. Brown had ordered him to take back Fort Pulaski. This fort was near the Savannah River and had been taken over by Federal forces. Bartow and the Oglethorpe Light Infantry successfully took the fort on June 15. This was largely thanks to his artillery, led by Colonel Alexander Lawton.

At the convention, Bartow was one of the strongest supporters of leaving the Union. He demanded that Georgia immediately withdraw from the Union. He helped Georgia join the states that wanted to secede. On January 19, 1861, the delegates voted 208 to 89 to leave the Union. Bartow voted in favor of secession and signed Georgia's Ordinance of Secession that day. The signing happened on January 21, 1861, in the public square outside the state capitol in Milledgeville. Bartow was then chosen to represent Georgia in the Provisional Congress of the Confederate States in Montgomery, Alabama. This began on February 4, 1861.

On the second day of the Congress, Bartow became the head of the Military Committee. He helped choose the color and style of the first Confederate gray uniforms. Later, Bartow announced that he would go to the battlefront in Virginia with his Oglethorpe Light Infantry.

Disagreement with Governor Brown

Bartow sent a message to his Georgia troops, telling them to get ready quickly. However, Governor Brown stopped his plans. Brown wanted to keep Georgia's armed forces only for the defense of Georgia. Bartow then asked Confederate President Jefferson Davis for help. He used a new law that allowed citizens to offer military help directly to the President, without state approval.

President Davis quickly approved Bartow's plan. He made Bartow the commander of the new Confederate force. This made Bartow's Oglethorpe Light Infantry the first company to officially serve the Confederacy's national war effort.

An angry Governor Brown responded by publishing a strong letter in all Georgia newspapers on May 21, 1861. He claimed that Bartow was seeking fame for himself and trying to get a higher rank. Brown said Bartow was leaving the war in Georgia "to serve the common cause in a more pleasant summer climate." He also said that the muskets Bartow's men carried to Virginia were only for local "public service." Brown claimed he had the power to take weapons from local military companies. He also suggested that Bartow had written the new law to help his own plans. This, Brown argued, forced Davis to ignore the authority of the Confederacy's "independent" states. Brown believed that, according to the Confederate Constitution, the governor was Bartow's only officer. He felt that Congress was taking away Georgia's rights.

Despite this, Bartow arrived in Savannah on May 21. He gathered his 106 soldiers and arranged for a train to take them to Virginia. A large crowd of happy citizens gathered at the station. Other local military groups fired an artillery salute to honor Bartow. Before leaving, Bartow said his most famous words: "I go to illustrate Georgia." This meant he would bring honor to Georgia.

On June 14, from Camp Defiance in Harper's Ferry, Bartow wrote his reply to Brown's "rude letter." He said Brown had published it while Bartow was away. The response was printed in the Savannah Morning News. Bartow strongly defended himself. He countered each of Brown's personal attacks. He stated that he was fighting under the command of Jefferson Davis alone. His main point was that the "Confederate Government is alone in charge of questions of peace and war." He said it had "the only right, except in case of invasion, to raise and keep armies." He argued that governors were not "allowed to raise these armies." Bartow said Brown was making "his common error, of thinking that he was the State of Georgia." He added, "a mistake in which I do not participate."

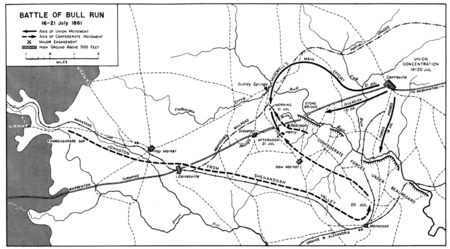

The Battle of Manassas

Bartow's 21st Oglethorpe Light Infantry finally reached Richmond, Virginia. Their goal was to protect the area from any Union attack. On June 1, 1861, Bartow was promoted to Colonel of the 8th Georgia Infantry. This group had been formed in Virginia from companies arriving from different Georgia counties. Later that day, he gathered the regiment for the first time at Camp Bartow in Richmond. The regiment was first sent to the Shenandoah Valley. They crossed the Virginia Piedmont and arrived in Winchester. Once there, Bartow added some local forces to his group.

In late June 1861, Bartow was ordered to move his troops near Manassas. They were to support General P. G. T. Beauregard. They left on June 19. They crossed the Shenandoah River with their "luggage tied on the ends of their fixed bayonets." After reaching the Piedmont station, the regiment traveled to Manassas by train.

Bartow commanded the 7th and 8th Georgia Regiments. The 9th Georgia Regiment and other battalions stayed behind. He spoke to his troops, saying, "... but remember, boys, that battle and fighting mean death, and probably before sunrise, some of us will be dead." Early the next morning, Bartow had the 7th and 8th Georgia march to the left side of the army.

After the fighting began, the two regiments reached Henry House Hill. Bartow joined them there after one of his soldiers confirmed it was his regiment. He asked, "Boys, what Regiment is this?" The answer came, "8th Georgia." He replied, "My God, boys, I am mighty glad to see you." He placed his brigade on the hill next to Brigadier-General Barnard Bee's brigade. Bee then decided to move forward to help another brigade. Bartow placed the 7th and 8th Georgia to support Bee's Brigade.

As the hours passed, Bartow's soldiers grew tired from fighting. Sometimes, they were completely surrounded and shot at from all sides. One survivor later wrote that "Practically half of the Eighth's 1,000 Georgians fell dead or wounded, or were captured or lost." He added that "Bartow led his men to an exposed high point which was too dangerous to hold."

Bartow, now with fewer than 400 men, had to retreat back to where he started. There, he asked General Beauregard, "What shall now be done? Tell me, and if human efforts can avail, I will do it." Beauregard pointed to the enemy at Stone Bridge and said, "That battery should be silenced." Bartow gathered the rest of the 7th Regiment and attacked again. Near Henry House Hill, Bartow's horse was shot, and he was slightly wounded. Still, he got another horse and kept fighting.

At one point, he encouraged his troops to follow him toward the enemy. He cheered "Boys, follow me!" and waved his cap. Just then, a bullet hit him in the chest, fatally lodging in his heart. Some of his soldiers gathered around him. They heard his last words: "Boys, they have killed me, but never give up the field." Francis Bartow died lying on the ground, held by Colonel Lucius Gartrell. He was the first brigade commander to be killed in action during the Civil War. Amos Rucker and Moses Bentley, two servants from the 7th Regiment, carried Bartow off the battlefield. A famous surgeon, H. V. M. Miller, tried to help him, but it was too late.

The rest of Bartow's 7th Georgia continued to follow his last command to attack. The Union forces were starting to get tired because Bartow's morning attack had weakened them. The Confederates kept attacking until they destroyed the enemy's artillery at Stone Bridge. General Beauregard said, "You Georgians saved me." However, the Georgia Rome Weekly Courier newspaper wrote, "Col. Bartow's fine Regiment of Georgians were nearly wiped out."

When the Provisional Congress heard about Bartow's death, they stopped their meetings. This was "to show their respect for his memory," as stated by their spokesman, T. R. R. Cobb. The group felt "true sadness" because of the "heavy loss suffered by the Confederacy." They confirmed Bartow's rank of acting brigadier general, given after his death.

On July 27, 1861, Bartow's body returned to Chatham County, Georgia. A large crowd gathered, and Bartow was buried at Laurel Grove Cemetery with a military ceremony. Louisa Berrien received a comforting letter from Mrs. Jefferson Davis. His granite monument has two of his historical phrases carved under a wreath and a saber: "I go to illustrate Georgia" and "They have killed me, boys, but never give up."

Memorials to Francis Bartow

Manassas Battlefield Markers

After the battle, Confederate soldiers placed a small stone marker where Bartow was killed. It was carved in Savannah and quoted his last words: "My God, boys, they have got me, but never give up the field." Union forces later removed this stone during one of their raids. Today, two markers are at that spot in the National Battlefield. One is older, placed by veterans of the 7th Georgia in 1903. The other is a newer bronze marker from the 20th century.

On September 4, 1861, the first monument dedicated to the Confederacy was opened at Manassas. It honored Francis Bartow. This marble monument was mysteriously stolen in 1862. In 1936, the Georgia Division of the United Daughters of the Confederacy placed a new marker at the same spot to fix this damage. A new monument to Bartow is also nearby, a few feet from the original one.

Savannah's Monument

After delays caused by the war, the Savannah City Council approved a memorial on February 7, 1890. It honored local heroes Francis Bartow and Lafayette McLaws. Their two bronze busts were placed on stone stands in Chippewa Square in 1902. Bartow's bust faced south, and McLaws' faced north. Around 1910, the council decided to build the Oglethorpe Monument in Chippewa Square. So, both generals' busts were moved to the Confederate Monument at Forsyth Park.

Bartow is buried in Savannah's Laurel Grove Cemetery.

Places Named After Bartow

Many places and things have been named after Francis Bartow:

- Bartow County, Georgia

- Bartow, Georgia

- Bartow, Florida

- Bartow, West Virginia

- Bartow Elementary School in Savannah opened in 1963. It was later renamed Otis J. Brock Elementary School.

- In 1968, in Bartow, Florida, two schools merged to become Bartow High School.

- The SS Francis S. Bartow was a Liberty ship (a type of cargo ship).

- Francis Bartow Homes is an apartment community in Savannah, Georgia.

During the Civil War, several Georgia military companies were named after Bartow:

- Macedonia Silver Grays

- Company B, 10th Battalion Georgia Cavalry - Bartow Mounted Infantry

- Company C, 10th Battalion Georgia Cavalry - Bartow Raid Repellers

- Georgia Volunteer Infantry

- Company A, 23rd Regiment - Bartow Yankee Killers

- Company B, 40th Regiment - Bartow Sentinels/Howard Guards

- Company I, 40th Regiment - Bartow Rangers

The Francis S. Bartow Camp No. 93 is part of the Sons of Confederate Veterans. The Georgia General Assembly recently recognized this group for "protecting and preserving Confederate heritage."

See also

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |