Photographers of the American Civil War facts for kids

The American Civil War was the most photographed conflict of its time. These pictures gave people a clear look at the war and its important leaders. They made a big impact on everyone.

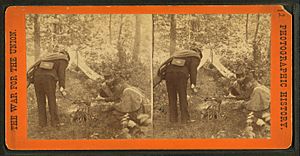

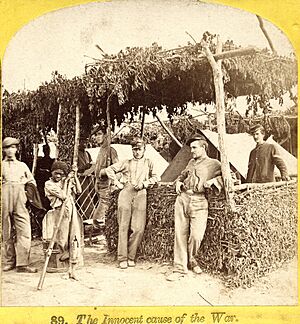

Did you know that about 70% of the war's photos were taken with a special camera called a stereo camera? This camera had two lenses. The American Civil War was the first war where people at home could see the real truth of battle. They saw it through newspaper pictures, small album cards, and a new 3D format called a "stereograph" or "stereoview." Millions of these cards were sold to people who wanted to experience the war in a new way.

Contents

- History of War Photography

- Northern Photographers

- Mathew Brady

- Alexander Gardner

- George N. Barnard

- Timothy H. O'Sullivan

- James F. Gibson

- Andrew J. Russell

- Thomas C. Roche

- Jacob F. Coonley

- Sam A. Cooley

- John Reekie

- David B. Woodbury

- David Knox

- William R. Pywell

- William F. Browne

- Isaac G. and Charles J. Tyson

- George Stacy

- Frederick Gutekunst

- E. T. Whitney

- Jeremiah Gurney

- G. O. Brown

- Haas and Peale

- John Carbutt

- Bierstadt Brothers

- Henry P. Moore

- Southern Photographers

- Secret Photography

- Traveling Photographers

- Taxes on Photos

- Copyright and Photography

- Legacy of Civil War Photography

- Photographer Portraits

- See also

History of War Photography

The American Civil War (1861–1865) was the fifth war ever to be photographed. Before it, photos were taken during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848), the Crimean War (1853–1856), the Indian Rebellion of 1857, and the Second Italian War of Independence (1859).

Northern Photographers

Many photographers from the North helped capture the Civil War. They traveled with the armies and took pictures of battles, soldiers, and important places.

Mathew Brady

Mathew B. Brady (1822–1896) was born in New York. He became a famous portrait photographer in New York City in the 1840s. He wanted to create a "Gallery of Illustrious Americans" to preserve the faces of important people.

Brady became known as the most important photographer of the Civil War. He spent a lot of his own money to collect as many war photos as possible. He believed that one day, these photos could be easily copied and shared. He bought, traded, and copied many pictures. Because of this, many war photos became known as "photographs by Brady," even if he didn't take them himself.

At the start of the war, Brady got permission to document the conflict. He bought strong cameras and mobile "darkrooms" (places to develop photos). He sent his employees to photograph the war. The First Battle of Bull Run was the first big chance to photograph a battle. Brady himself didn't get any known photos from that battlefield.

By the end of the war, Brady had spent about $100,000 and collected over 10,000 negatives. But the public wasn't as interested anymore. In 1875, the War Department bought the rest of his collection for $25,000. Mathew Brady died without money in 1896, but he was visited by friends until the end.

While Brady started the effort, it was often his employees, especially those working for Alexander Gardner, who followed the armies and took many of the actual war photos.

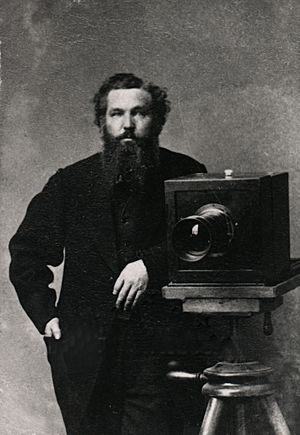

Alexander Gardner

Alexander Gardner (1821–1882) was born in Scotland. He first worked as a jeweler, but then became interested in finance and journalism. He also loved chemistry, which led him to photography.

In 1856, Gardner moved to the United States. He found work with Mathew Brady and managed Brady's studio in Washington D.C. Gardner was very good at business and at a type of photography called "wet-plate photography." He also excelled at making large prints.

In 1861, Gardner became an official photographer for General George B. McClellan. He was given the honorary rank of captain. He kept the title "Photographer to the Army of the Potomac" until the end of the war.

In 1862, Gardner and his team photographed the 1st Bull Run battlefield, McClellan's Peninsula Campaign, and the battles of Cedar Mountain and Antietam.

By May 1863, Gardner opened his own studio in Washington City. Many of Brady's former staff joined him. In July 1863, Gardner and his employees, James Gibson and Timothy O'Sullivan, photographed the battlefield of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

In April 1865, Gardner photographed the people arrested for planning to assassinate President Abraham Lincoln. He also photographed the execution of some of these conspirators in July 1865. Later, he photographed the execution of Henry Wirz, a commanding officer at a prisoner of war camp.

In 1865 and 1866, Gardner published his two-volume book, Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the War. It contained 100 large photos with descriptions. It was expensive, so it didn't sell as well as he hoped.

Gardner retired from photography in 1879. He spent his later years working on a life insurance business and helping Scottish relief organizations.

George N. Barnard

George Norman Barnard (1819–1902) was born in Coventry, Connecticut. He started a photography studio in New York and became known for his portraits. In 1853, he took what might be the first American "news" photograph of a large fire.

When the war started, Barnard worked for Mathew Brady. He took portraits and photographed troops around Washington D.C. He was one of Brady's first photographers sent to battlefields in Northern Virginia.

Barnard is most famous for his 1866 book, Photographic Views of Sherman's Campaign. This book had 61 large photos of scenes from the war, including the Atlanta Campaign and Sherman's March to the Sea.

After the war, he continued to take photos. His studio in Chicago was destroyed by the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. He later worked with George Eastman, who founded Kodak. George Barnard died in 1902 at age 82.

Timothy H. O'Sullivan

Timothy H. O'Sullivan (1840–1882) was born in New York City. As a teenager, he worked for Mathew Brady. Later, he was hired by Alexander Gardner to manage his field work.

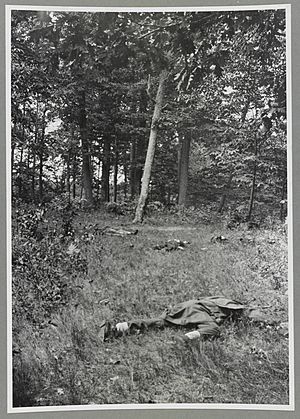

In 1861–62, O'Sullivan documented military operations in South Carolina. In July 1862, he followed General John Pope's campaign in Virginia. A highlight of his career was taking pictures at Gettysburg, PA, in July 1863. His most famous photo from there is "The Harvest of Death."

In 1864, he photographed during the Siege of Petersburg and the siege of Fort Fisher. He also took pictures at Appomattox Court House in April 1865. Forty-five of the 100 photos in Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book Of The War are credited to O'Sullivan.

After the Civil War, O'Sullivan became an official government photographer for several expeditions exploring the American West. His photos were among the first to show prehistoric ruins, Navajo weavers, and Pueblo villages. These pictures helped attract settlers to the West.

O'Sullivan returned to Washington, D.C., in 1875. He worked as the official photographer for the Treasury Department. He died young, at age 42, from tuberculosis in 1882.

James F. Gibson

James F. Gibson (1828–?) was a less known but important Civil War photographer. He was from Scotland, like Alexander Gardner, and may have moved to America with him. In 1860, he was working for Mathew Brady.

Gibson's first documented trip to the field was with George N. Barnard in March 1862. He worked with Gardner at Gettysburg and Sharpsburg. His most important work was the many photos he took on the Virginia peninsula. This includes his moving picture of the wounded at Savage Station, Virginia.

After the war, Gibson had a legal dispute with Mathew Brady. He then left for Kansas and was not heard from again.

Andrew J. Russell

Andrew J. Russell (1829–1902) was born in New Hampshire and grew up in New York. He was interested in painting, especially railroads and trains. At the start of the Civil War, he painted a diorama to help recruit soldiers for the Union Army.

In 1862, Russell joined the army as a captain. In 1863, he learned the "wet-plate collodion process" of photography. His first photos were used by Brigadier General Herman Haupt. Haupt was impressed and assigned Russell to the United States Military Railroad Construction Corps. This made Russell one of only two non-civilian Civil War photographers.

Russell took over a thousand photos in two and a half years. Some were even sent to President Lincoln. He is probably best known for his photo "Stone wall at foot of Marye's Heights, Fredericksburg, Va." This picture shows dead Confederate soldiers. Andrew Russell died in 1902 in Brooklyn, New York.

Thomas C. Roche

Thomas C. Roche (1826–1895) became interested in photography in 1858. In 1862, he started working for Anthony Co., a major photography supplier. He took the first complete set of stereoviews of Central Park for them.

Roche was a very important photographer and advisor for Anthony Co. He developed many patents for their products. His most important patent, in 1881, was for a "dry plate" process. This new method made "wet plate" photography, which was much harder, less common.

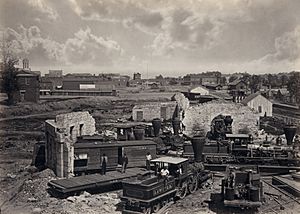

Roche is best known for the about 50 stereoviews he took on April 3, 1865, after the fall of Petersburg, Virginia. These included many pictures of the dead, especially inside Fort Mahone. He lived comfortably from his patents and continued to share his knowledge until his death in 1895.

Jacob F. Coonley

Jacob Frank "Jay" Coonley (1832–1915) was a landscape painter who learned photography from George N. Barnard. He managed Edward Anthony's stereoscopic print shop until 1862. During the war, Coonley stayed in Washington, photographing generals, soldiers, and statesmen.

In 1864, he was given a contract to photograph along the railroads held by the U.S. in Alabama, Georgia, and Tennessee. He also created the Nashville series for Edward Anthony. Coonley likely took at least 14 photos of the Fort Sumter Flag-Raising Ceremony on April 14, 1865.

After the war, Coonley managed galleries in Charleston, S.C., and Savannah, Georgia. He also had a business in Nassau, Bahamas, for many years. He returned to New York in 1881 and continued to spend his winters in the Bahamas. He died in 1915.

Sam A. Cooley

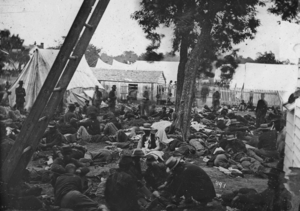

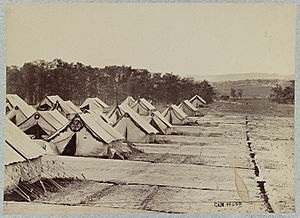

Samuel Abbot Cooley (1821–1900) was from Connecticut. He was a photographer in the Beaufort area before the war. He stayed in the occupied area as a photographer for the X Corps. He used large cameras and twin-lens stereo cameras.

By 1863, Cooley had a photography studio above his store. He sold his business in May 1864, planning to return North. However, he came back to Beaufort in 1865. He opened a store and advertised himself as "Photographer, Department of the South," doing work for the government.

Cooley advertised that he had over two thousand different negatives. These included views from Charleston, S.C., to St. Augustine, Florida. He also opened galleries in Hilton Head, S.C., and Jacksonville, Florida. He eventually returned home to Hartford, Connecticut, in 1869. Sam Cooley died in 1900.

John Reekie

John Reekie (1829–1885) was another lesser-known Civil War photographer. He was a Scotsman who worked for Alexander Gardner. Reekie took photos in Virginia, including Dutch Gap, City Point, Petersburg, Mechanicsville, and Richmond.

Reekie is best known for his photos of the unburied dead on the battlefields of Gaines' Mill and Cold Harbor. One of his most famous photos, "A Burial Party, Cold Harbor," shows African American soldiers gathering human remains almost a year after the battle. This photo is important because it shows black soldiers working during the war.

John Reekie was an officer of the Saint Andrews Society, a Scottish relief organization in Washington D.C. He died in 1885 from pneumonia.

David B. Woodbury

David B. Woodbury (1839–1879) was considered one of the best artists who stayed with Mathew Brady throughout the war. In March 1862, Brady sent Woodbury and Edward Whitney to photograph the 1st Bull Run battlefield. In May, they took pictures of the Peninsula Campaign.

In July 1863, Woodbury and Anthony Berger photographed the Gettysburg battlefield for Brady. They returned on November 19 to take pictures of the crowd and procession for the dedication of the Soldier's National Cemetery.

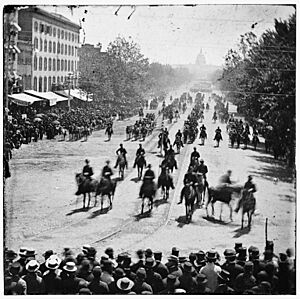

In the summer of 1864, Woodbury photographed Grant's Headquarters Command for Brady. On April 24, 1865, Woodbury helped J.F. Coonley photograph the Grand Review of the Army in Washington D.C. This was a huge parade of Union soldiers. David B. Woodbury died in 1866 in Gibraltar, where he had gone for his health.

David Knox

David Knox (1821–1895) was born in Scotland. He moved to America in 1849 and worked as a machinist. In 1856, he moved to Springfield, Illinois, living one block from Abraham Lincoln's home.

The first mention of Knox working at Mathew B. Brady's studio is a telegram from Alexander Gardner in 1862. Knox was likely trained by Gardner to use a large camera. He later joined Alexander Gardner's new company.

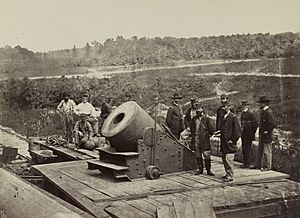

Four of Knox's wartime photos were included in "Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the War." He is probably best known for his famous photo, "13 inch mortar Dictator, in front of Petersburg, Va." Like his colleagues, Knox was an officer of the Washington D.C. Saint Andrews Society, a Scottish relief organization.

In 1870, David Knox moved to Omaha, Nebraska. He stopped photography and became head of the Union Pacific Railroad machinist shops. He died in 1895.

William R. Pywell

William Redish Pywell (1843–1887) worked for both Mathew Brady and Alexander Gardner. His photographs are an important part of the Civil War's history. Three of his photos are in Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the War.

Pywell worked in both the Western and Eastern parts of the war. He is probably best remembered for his early photos of the slave pens in Alexandria, Virginia. These pens were used to hold enslaved people before they were sold.

After the war, Pywell assisted Alexander Gardner on a railway survey in Kansas in 1867. Six years later, he was the official photographer for the 1873 Yellowstone Expedition. This expedition explored a route for the Northern Pacific Railroad.

William F. Browne

William Frank Browne (?–1867) was born in Vermont. At the start of the war, he joined the 15th Vermont Infantry. After his two-year service, Browne became a freelance photographer for the 5th Michigan Cavalry. He took some of the earliest photos of Brigadier General George A. Custer.

In 1864–65, Browne started working for Alexander Gardner. In May 1865, he was assigned to photograph the James River water batteries around Richmond, Virginia. These photos helped preserve a record of their strength. After the war, Gardner published 120 of Browne's photos as "View of Confederate Water Batteries on the James River." Browne returned to Vermont and died of tuberculosis in 1867.

Isaac G. and Charles J. Tyson

Isaac Griffith (1833–1913) and Charles John (1838–1906) Tyson lived in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in July 1863. Their photography studio wasn't ready for field photography at the time. The Tyson brothers left town before the battle.

After the visits to the battlefield by Alexander Gardner and Mathew B. Brady, the Tyson brothers got the right equipment. By December, they were offering "Photographic Views of the Battle-Field of Gettysburg." On November 19, they took historic photos of the procession for the dedication of the Soldier's National Cemetery. One of these photos captured President Lincoln on horseback. William H. Tipton, who was learning from the Tysons, took over their gallery in 1868.

George Stacy

George Stacy (1831–1897) was a Civil War field photographer. He later became a publisher of stereoviews, which were not always his own photos. He had a storefront in New York City from 1861 to 1865.

His earliest confirmed stereoviews are from the Prince of Wales' visit to Portland, Maine, in 1860. In June 1861, Stacy took his famous Fortress Monroe series of photos. An industry record shows that Stacy was still selling stereoviews in 1870. He was also listed as a farmer, suggesting he might have done photography in the winter and farming in warmer months.

Frederick Gutekunst

Frederick Gutekunst (1831–1917) was a Pennsylvania photographer. He opened two studios in Philadelphia in 1856. Just six days after the Battle of Gettysburg, on July 9, he produced a series of high-quality large photos. These included the first image of local hero John L. Burns.

An elegant portrait of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant made him even more famous. By 1893, he had been in business for almost 40 years. Gutekunst died in 1917.

E. T. Whitney

Edward Tompkins Whitney (1820–1893) was born in New York City. In 1844, he learned the daguerreotype process. He later learned the "wet-plate collodion photography" process. Whitney opened his own gallery in Rochester in 1851. He often visited Mathew Brady's studio to learn the latest photography techniques.

In 1859, Whitney moved to New York City and opened a gallery with Andrew W. Paradise, who was Mathew Brady's assistant. During the winter of 1861–62, Brady hired Whitney to take photos of the fortifications around Washington D.C. and other important places for the government.

In March 1862, Brady sent Whitney and David Woodbury to photograph the Bull Run battlefield. Whitney also said he took photos at Yorktown, Williamsburg, and other locations during McClellan's Peninsula Campaign. Whitney appears in many photos from 1861 to 1863. However, there are no wartime photos specifically credited to him.

Jeremiah Gurney

Jeremiah Gurney (1812–1895) was born in New York. He became one of the first students in America to learn the "new art" of daguerreian photography in 1839. He opened his own gallery in New York City in 1843.

In the 1850s, "Gurney's Daguerreian Gallery" offered very large daguerreotype prints. In 1852, he took time off to recover from mercury vapor poisoning, a common illness for daguerreotype photographers.

Jeremiah Gurney is probably best known for taking a photograph of Abraham Lincoln in his open coffin on April 24, 1865. This happened when the President's body was lying in state in New York City Hall. Mary Lincoln, the President's wife, had forbidden any photos of her husband's body. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton was very angry and took all the prints and negatives, except for one. That one print was hidden by Lincoln's secretary, John Hay, and found in 1952. Gurney died in 1895.

G. O. Brown

George Oscar Brown was active from 1860 to 1889, but not much is known about him. In April 1866, Brown, who was a hospital steward at the Army Medical Museum, was hired as an assistant cameraman. His job was to photograph medical items like bones and skulls on the Wilderness and Spotsylvania battlefields in Virginia.

Even though he was new to photography, Brown did good work. He produced several stereo photographs that help us understand those terrible battles. In 1868, Brown was listed as a photographer at the Medical Museum. He later promoted and taught others about the "Porcelain Print" process. Brown's trail is lost after 1873.

Haas and Peale

Philip Haas (1808–1871) and Washington Peale (1825–1868) were photographers during the Civil War. Not much is known about their early lives. Haas was a lithographer who learned daguerreotype photography. By 1852, he had a studio in New York City.

In 1861, Haas joined the 1st N.Y. Engineers. In 1863, Haas and his new assistant, Washington Peale, took photos of General Quincy Gilmore's siege operations on Morris Island. They are credited with many photos of the Union Army's activities in South Carolina. These include photos of Folly Island, Fort Sumter, and Charleston Harbor.

Haas left the army due to poor health in May 1863, but he kept taking photos for the War Department. One of their most important photos is "Unidentified camp." This photo is believed to be one of the world's first photographs of actual combat. It shows ironclad warships, including U.S.S. New Ironsides, in action off Morris Island, South Carolina.

John Carbutt

John Carbutt (1832–1905) was born in England and first came to Canada. He is first mentioned in the United States in the Chicago city directory of 1861. In the 1860s, Carbutt took many stereoviews of Chicago, the Mississippi River, and the American West. His Western photos included the building of the Union Pacific Railroad and portraits of Native Americans.

Carbutt is perhaps best known for his important work in improving photography. He was one of the first to experiment with magnesium light in 1865. He also worked with dry plates as early as 1864 and started making them for sale in 1879. In 1896, Carbutt and Dr. Arthur W. Goodspeed produced some of the earliest X-ray photographs.

His Civil War photos are not as well known. The largest collection of his Civil War photos are about 40 stereoviews of the 134th Illinois Infantry camped in Columbus, Kentucky, in 1864. Carbutt also photographed Lincoln's funeral train as it passed through Chicago in 1865.

Bierstadt Brothers

The Bierstadt Brothers were Edward (1824–1906), Charles (1828–1903), and Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902). They moved from Germany to Massachusetts in 1831. The brothers opened a photography gallery in New Bedford, Massachusetts, which they ran from 1859 to about 1867.

Albert seems to have been the main person behind their Civil War photos. In October 1861, he and his friend Emanuel Leutze got permission to travel, photograph, and sketch along the Potomac River near Washington, D.C. They took 19 stereoview photos of wartime Washington D.C. and its defenses. These photos showed Union pickets and scenes at Camp Griffin.

Edward also ran a temporary studio near Camp Griffin. The Bierstadt Brothers also published 8 views of the Metropolitan (Sanitary) Fair in New York City in April 1864. After their partnership ended around 1867, Albert became a famous artist known for his paintings of the American West. Edward and Charles continued their careers as photographers.

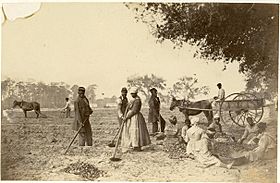

Henry P. Moore

Henry P. Moore (1835–1911) was born in New Hampshire. By 1862, he was a "well known" photographer in Concord, New Hampshire. He started taking Civil War photos when he followed the Third New Hampshire Regiment soldiers to Hilton Head, South Carolina, in February 1862.

His photography studio on Hilton Head Island was a tent set up in a sandy cotton field. He took at least one more trip to the area in 1863. He used glass plate negatives that measured 5 x 8 inches. Photos were sold at his gallery for one dollar each.

Moore produced more than 60 photos of the South. These included extensive coverage of the Third New Hampshire Regiment, as well as other military units and navy ships. He also photographed plantations and recently freed slaves. He showed cotton processing, slave quarters, and "contrabands" (escaped slaves) harvesting sweet potatoes. Moore continued as a photographer after the war. He died in 1911.

Southern Photographers

In the early months of the war, Southern photographers actively documented events. A Southerner even took the first photos inside Fort Sumter. However, due to the war and high inflation, most Southern photographers soon went out of business. Many war photos were later destroyed in the South. Luckily, many family portraits of Confederate soldiers survived. These photos are often the last known record of what these soldiers looked like.

George S. Cook

The most famous Southern photographer was George Smith Cook (1819–1902). He was born in Stamford, Connecticut. He became a portrait painter and then a daguerreotype photographer, settling in Charleston, South Carolina.

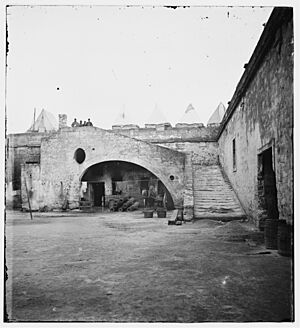

Cook became famous partly because of his visit to Fort Sumter on February 8, 1861. He took a photo of the fort's commander, Maj. Robert Anderson. This photo was mass-marketed as small cards called cartes-de-visite. Cook also systematically documented the Union shelling of Charleston and Fort Sumter.

On September 8, 1863, he and his business partner James Osborn photographed inside Fort Sumter. They also captured the naval action in the harbor, showing Federal ironclads firing on Fort Moultrie. These historic images show three ironclad monitors and U.S.S. New Ironsides firing. For unknown reasons, this historic stereoview was not sold until 1880 by Cook's son.

Sadly, Cook's large collection of photos, mostly portraits of important Southerners, was lost in a fire in Columbia, S.C., in 1865. Cook moved his family to Richmond in 1880. He bought out other photographers' businesses, building a huge collection of photos of the former Confederate capital. Cook continued to be an active photographer for the rest of his life.

Note: The famous "exploding shell" photo often linked to Cook is actually a painting by C.S.A. Lt. John R. Key. It was based on three half-stereo photos taken by Cook inside Fort Sumter on September 8, 1863. Experts realized that cameras at that time could not take such a wide-angle picture.

Osborn & Durbec

In 1858, James M. Osborn (1811–1868) and Frederick Eugene Durbec (1836–1894) formed a partnership in Charleston, S.C. They quickly became some of the war's first photographers. By 1860, their studio was very successful, selling many stereoscopic instruments and pictures.

They both joined the Lafayette Artillery. Osborn & Durbec also took photos of the city and its surroundings, including historic scenes of plantations and slave life before the war.

After the Union surrendered Fort Sumter on April 14, 1861, Osborn visited the fort at least twice. He took at least 43 stereo images of the battle's aftermath. This is the largest known group of Confederate war photos and is considered the most complete photographic record of a Civil War battle. Thirty-nine of these photos are known to exist today.

Their business in Charleston ended by February 1862 due to the war and fires. In September 1863, Osborn and George S. Cook volunteered to photograph the inside of Fort Sumter, which had been heavily shelled. They didn't know that this visit would result in some of the first combat photographs in history.

J.D. Edwards

Jay Dearborn Edwards (1831–1900) was born in New Hampshire. After his father died, he moved to St. Louis and changed his last name to Edwards. By age 17, he was giving talks on phrenology (a pseudoscience) and started his photography career.

In 1851, he moved to New Orleans. He liked working outdoors from his "queer-looking wagon." Wet-plate photography allowed Edwards to sell his stereo views throughout New Orleans. He later formed a partnership and opened the Gallery of Photographic Art. This gallery specialized in "stereoscopic views of any part of the world."

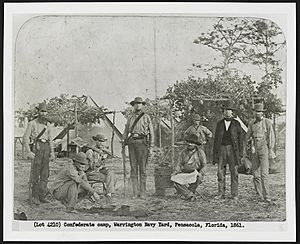

Edwards took one of the earliest wartime photo trips in April 1861. He followed Confederate units from New Orleans to Pensacola, Florida, as they prepared to fight Fort Pickens. Edwards advertised 39 views for "$1 per copy." Two of his photos were used in Harper's Weekly, but he didn't get credit. After this, Edwards seems to have gone out of business.

McPherson & Oliver

William D. McPherson (? – 1867) and Mr. Oliver (?–?) were photographers active in New Orleans and Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in the 1860s. Their business focused on Confederate subjects until Union forces took over Baton Rouge in May 1862. Like other Southern photographers in occupied cities, they quickly adapted. This allowed them to get photography supplies through special arrangements with the military.

McPherson & Oliver are probably best known for "The Scourged Back." This was a famous and widely published portrait of "Gordon," an escaped slave from Louisiana. Gordon came into Union lines in Baton Rouge, and his back showed severe scars from whipping.

The pair went to Port Hudson, Louisiana, in the summer of 1863 and photographed the difficult siege of that city. After Port Hudson fell in July, McPherson & Oliver photographed the captured Confederate forts. In August 1864, they made a complete photographic record of Fort Morgan after it was captured.

In 1864, they moved to New Orleans. Their partnership ended in 1865. McPherson continued with his own gallery until his death from yellow fever in 1867.

Charles Richard Rees

Charles Richard Rees (1860–1914) was born in Pennsylvania. He started his career as a daguerreotypist in Cincinnati around 1850. In 1851, Charles and his brother Edwin opened a studio in Richmond, Virginia.

By 1853, Charles had moved to New York City, which was a center for photography. Competition was tough, so "Professor" Rees claimed to be a European refugee with a new "German method" of photography. He cut his prices very low to compete.

After a few years, Charles left New York City. By 1859, he and his brother Edwin returned to Richmond, Virginia, which was soon to be the capital of the Confederacy. They opened a new studio called "Rees' Steam Gallery."

At the start of the Civil War, many politicians and soldiers came to Richmond. This meant a big increase in business for the Rees brothers. Charles joined the 19th Virginia Militia, a group used mainly as prison guards. As the war went on, there were shortages of everything, and most shops in Richmond, including Rees' studio, closed.

When Grant advanced on Petersburg in April 1863, Richmond was evacuated. Warehouses were set on fire, and the fires spread, destroying the business district, including the Rees Brothers' studio. However, rebuilding started quickly, and Rees opened a new studio.

In 1880, Charles moved his studio to Petersburg, Virginia. Charles Rees died in 1914 at age 84. His studio continued to operate under his son, James Conway Rees. The Rees Studio in Petersburg closed during the Great Depression.

Andrew D. Lytle

Andrew David Lytle (1858–1917) was a traveling photographer in Ohio. In 1858, he opened a studio in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. For the next 50 years, he photographed the people, places, and events of Louisiana's capital city.

Lytle's photo of the 1st Indiana H.A. is one of many he took in Baton Rouge when Union forces occupied it. After Federal forces took over Baton Rouge in May 1862, Lytle developed a good relationship with the U.S. Army and Navy. He took studio portraits for soldiers and photographed army camps and navy ships.

Many of Lytle's Civil War photos are kept in the 'Andrew D. Lytle's Baton Rouge' Photograph Collection at Louisiana State University. His studio was so successful during the war that he bought property near the Louisiana Governor's Mansion, which became his family home for 60 years. His son Howard later joined him in the business.

Julian Vannerson

Julian Vannerson (1827–?) was a portrait artist in Washington, D.C., in 1857. His autographed prints were published in a book of photographic portraits of Congress members in 1859. He also took portraits of Native Americans as part of an effort to document treaty delegations.

After the Civil War began, Vannerson worked out of Richmond. He continued to make portraits of famous Confederate generals, including Robert E. Lee, J.E.B. Stuart, and Stonewall Jackson. Vannerson closed his business and sold his equipment when the war ended.

Secret Photography

Some photographers tried to take pictures secretly during the war.

Andrew David Lytle

In 1910, a company publishing The Photographic History of the Civil War bought most of the photos taken by Baton Rouge photographer Andrew Lytle during the Federal occupation. They also spoke to Lytle's son, Howard, about his father's role in the war. From this conversation, the story of Lytle as a "camera spy for the Confederacy" began.

However, other than this story told 50 years later to a journalist, there is no other record of Lytle being a spy. Photography equipment at the time was bulky. Cameras were large and needed heavy tripods. They used wet-plate collodion glass-plate negatives, which needed long exposure times. A photographer in the field needed a darkroom wagon nearby to prepare and develop the wet plates before they dried. Without a darkroom wagon, plates would have to be quickly moved between the studio and the photo site.

Robert M. Smith

Confederate Lieutenant Robert M. Smith was captured and imprisoned at Johnson's Island, Ohio. He is unique because he secretly built a wet-plate camera using a pine box, a pocket knife, a tin can, and a spyglass lens. Smith got chemicals from the prison hospital for his photography. He used the camera secretly to photograph other prisoners in the attic of cell block four. No other prison had a photographer taking pictures for prisoners to send home. His work is well described in David R. Bush's book, I Fear I Shall Never Leave This Island: Life in a Civil War Prison (2011).

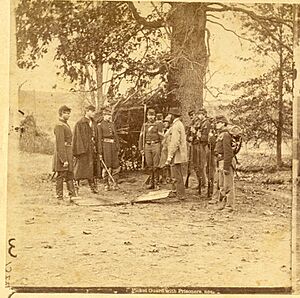

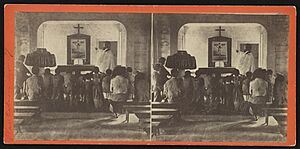

Traveling Photographers

Traveling photographers got permission from generals to set up studios in army camps. They did this mainly to take portraits of soldiers. These photos could then be sent to their families as a keepsake. This was a very profitable business.

Taxes on Photos

In September 1862, Northern photography studios had to buy a yearly license. By August 1864, photographers also had to buy revenue stamps. The "Sun Picture" tax on photographs was created to help pay for the war. The tax was 1¢, 2¢, 3¢, or 5¢, depending on the photo's price.

There wasn't a special stamp just for photos. So, U.S. revenue stamps originally meant for bank checks, playing cards, or other items were used. Thanks to the efforts of photographers like Alexander Gardner, Mathew Brady, and Jeremiah Gurney, the tax was removed in 1866.

Copyright and Photography

In 1854, James Ambrose Cutting and his partner, Isaac A. Rehn, got three patents for "improvements" in the wet-plate collodion process. Cutting developed a way to stick two pieces of glass together using Canada balsam. This was meant to seal ambrotypes to preserve them. However, the varnish layer already protected them well, and Cutting's method sometimes caused problems.

Many lawsuits and arguments about these patents may have discouraged the wider use of "instantaneous" (stop-action) photography during the Civil War. Cutting's patented formula included potassium bromide, which made the photographic material much more sensitive to light. When the patents came up for renewal in 1868, the Patent Office decided they should not have been issued in the first place. This was partly based on evidence from Henry Snelling's 1853 book, which described using the same key ingredients.

Another big concern for photographers in the 1800s was the lack of copyright protection. They called it "piratical stealing." In 1870, a new law was passed to address this. The changes in this law were mainly due to the influence of Alexander Gardner.

Legacy of Civil War Photography

The work of all Civil War photographers can be seen in almost every history book about the conflict. In terms of photography, the American Civil War is the best-documented conflict of the 19th century. It was an early example of wartime photojournalism, which later became very important in World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War.

The large number of Civil War photographs available is very different from the few pictures from later conflicts like the Russian wars in Central Asia, the Franco-Prussian War, and other colonial wars before the Boer War.

Photographer Portraits

See also

In Spanish: Fotógrafos de la Guerra de Secesión para niños

In Spanish: Fotógrafos de la Guerra de Secesión para niños

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |