Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park |

|

|---|---|

|

IUCN Category V (Protected Landscape/Seascape)

|

|

|

|

| Location | extending from Cumberland, MD to Georgetown, Washington, DC, United States |

| Nearest city | Washington, D.C. |

| Area | 19,586 acres (79.26 km2) |

| Established | September 23, 1938 |

| Visitors | 3,937,504 (in 2011) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park |

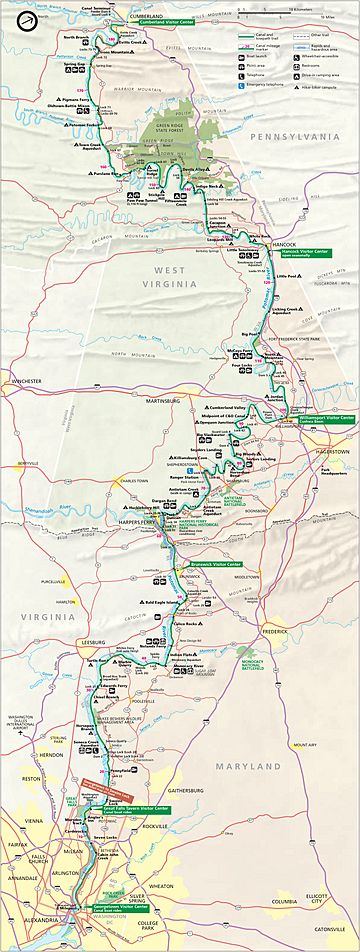

The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park is a special place in Washington, D.C. and Maryland. It was created in 1961 by President Dwight D. Eisenhower to protect the old Chesapeake and Ohio Canal and its original buildings. The canal and its walking path, called a towpath, stretch along the Potomac River for 184.5 miles (296.9 km) (about 296.9 kilometres (184.5 mi)) from Georgetown, Washington, D.C. to Cumberland, Maryland. In 2013, this path became the first part of U.S. Bicycle Route 50.

Contents

History of the C&O Canal

Building the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, also known as "the Grand Old Ditch," started in 1828. It was finished in 1850 when it reached Cumberland, Maryland. The canal was supposed to go all the way to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, but it never made it. Even though the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) reached Cumberland eight years before the canal, the canal was still useful for a while. It wasn't until the mid-1870s, when trains got bigger and faster, that the railroad could offer cheaper prices than the canal, which sealed its fate.

The C&O Canal was open from 1831 to 1924. Its main job was to carry coal from the Allegheny Mountains to Washington D.C. The canal closed in 1924 because several big floods badly damaged it and made it too expensive to fix.

The Government Buys the Canal

In 1938, the United States government bought the old canal from the B&O Railroad. They wanted to fix it up as a fun place for people to visit. It also helped create jobs for people who didn't have work during the Great Depression. By 1940, the first 22 miles (35 km) of the canal, from Georgetown to Violettes lock, were repaired and filled with water again. African-American workers from the Civilian Conservation Corps did this important work. In 1941, the first Canal Clipper boat started giving rides pulled by mules.

The restoration work stopped when the United States joined World War II. Resources were needed for the war effort. In 1942, big floods damaged the repaired parts of the canal. An official from the National Park Service (NPS) pushed for the canal to be fixed again. This was because it could supply water to the Dalecarlia Reservoir if other water pipes were damaged during the war. Since this became a matter of national safety, the work was approved and funded by 1943. The Park Service started boat trips again in October 1943.

Some people in Congress wanted to turn the canal and towpath into a road for cars. But because of floods, the Army Corps of Engineers suggested building 14 dams. These dams would have flooded 74 miles of the towpath and important structures like the Monocacy Aqueduct. The NPS worked with the Corps to preserve parts of the canal, as keeping the whole canal working was too costly.

Becoming a National Park

The Douglas Hike

Not everyone liked the idea of turning the canal into a road. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas was one of them. In March 1954, he led an eight-day hike along the towpath from Cumberland to D.C. Many people joined for parts of the hike, but only nine, including Douglas, walked the entire 184.5 miles (297 km). After this hike, Justice Douglas started a group, later called the C&O Canal Association, to protect the canal. His dedication helped make the park a reality.

Towpath for Biking

In 1958, the entire towpath was cleared for hiking. A 12 miles (19 km) (about 19 kilometres (12 mi)) bicycle trail was built on the towpath from Georgetown to Widewater, Maryland. This bike trail opened on November 22, 1958, and by 1960, cyclists were riding the full route.

From Monument to Park

In 1961, President Dwight D. Eisenhower declared the canal a national monument. This made some people even more against making it a national park. Some preferred to make the Potomac River a national river instead. However, within ten years, opinions changed. The idea of turning the canal into a historic park gained support. The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park Act was signed into law by President Richard Nixon on January 8, 1971, officially making it a National Historical Park.

Floods of 1996

In 1996, the park experienced two major floods. After a big snowstorm in January, heavy rains caused extreme flooding. This winter flood covered 80 to 90 percent of the canal and towpath. The floods caused a lot of damage to the towpath and the canal's structures. Many volunteers were needed to help clean up. Then, in September, Hurricane Fran caused even more damage. It took a lot of time and money to repair and rebuild the towpath and refill parts of the canal with water.

Restoration Efforts

Today, several groups work to keep the park beautiful and preserve its history. The C&O Canal Trust, started in 2007, is a non-profit partner of the National Park Service. The C&O Canal Association, formed in 1954, is a volunteer group that helps protect the canal and the Potomac River. They work together to fix damaged parts of the canal, repair the towpath, and keep sections of the canal watered for visitors and wildlife. They also teach people about the canal's history at six visitor centers along the canal: Georgetown, Great Falls Tavern, Brunswick, Williamsport, Hancock, and Cumberland.

Current projects include fixing and rewatering the Conococheague Aqueduct, repairing Locks 3 and 4, and working at Great Falls (Lock 20) and Swain's Lock (Lock 21). Work on the Paw Paw Tunnel also started in 2019.

The Park Today

What the Park Includes

The park covers almost 20,000 acres (about 80 square kilometers) along the Potomac River. A small part of the towpath near Harpers Ferry National Historical Park is also part of the Appalachian Trail.

The canal starts at its "zero mile marker" in Georgetown, right by the Potomac River. This spot is across from the Watergate complex. Some people think the Watergate complex got its name because it's right next to the canal's large wooden "water gate."

Flooding still threatens the historical structures in the canal. The Park Service has refilled some parts of the canal with water, but most of it remains dry.

How People Use the Park

The canal and its towpath offer many activities. You can go running, hiking, biking, fishing, boating, and kayaking. Some areas even allow rock climbing. The canal is also a great place to see different kinds of wildlife and birds.

The seven National Park Service visitor centers have displays and exhibits about the canal's history. The park offers rides on two replica canal boats, the Georgetown and the Charles F. Mercer. These boats are pulled by mules. Park rangers in historical costumes work the locks and tell stories about the canal's past.

About five million people visit the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park each year. You have to pay to enter through the Great Falls Tavern Visitor Center, but most other access points to the park are free.

Hiker-Biker Campsites

The National Park Service has many hiker/biker campsites located about every 5–7 miles (8–11 km) along the towpath. These campsites are free and available first-come, first-served. Each site has a water pump (available from mid-April to mid-November), a picnic area, a firepit, and a latrine.

Other Camping Options

The C&O Canal NHP also has campsites for tents and small RVs. These are for individuals and groups up to 35 people. Not all campsites have the same features, but they might offer parking, restrooms, picnic tables, boat ramps, or nearby shops. Hiker-biker campsites are free for one night per trip. Drive-in (car) campsites now require reservations through Recreation.gov. Group campsites cost $40 during busy times and $20 during quieter times.

| Towpath Mileage | Campsite | Type | Fee per Night | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11.0 | Marsden Tract | Group | $40/20 | Permit required |

| 69.9 | Antietam Creek | Car | $20 | |

| 110.4 | McCoys Ferry | Car, Group | $20 | |

| 140.9 | Fifteenmile Creek | Car, Group | $20 | |

| 156.1 | Paw Paw Tunnel | Car, Group | $20 | |

| 173.3 | Spring Gap | Car, Group | $20 |

Images for kids

Going 184.5 miles (296.9 km) upstream from Georgetown to Cumberland, Maryland.

-

The Rock Creek Basin, just before the Tidewater Lock.

-

George Washington's Patowmack Canal, used as a feeder, goes to the left, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal goes to the right.

-

This spot here was called the "Log Wall": builders put a log wall here, filled with rubble, to make the canal. Hurricane Agnes washed it out completely in 1972, and the NPS erected this retaining wall without logs.

-

Cliff face at the Billy Goat Trail in Maryland.

-

Great Falls Tavern on the C&O canal in Potomac, Maryland.

-

Ruins of an abandoned granary, below the Monocacy Aqueduct.

-

Lock 28 near Point of Rocks, Maryland.

-

Lock 33 near Harpers Ferry, West Virginia.

-

Cushwa Basin and Visitor Center at Williamsport, Maryland.

-

The canal at Hancock, Maryland.

-

Lock 69 pool at Oldtown, Maryland.

-

Evitts Creek Aqueduct, the final aqueduct on the C&O Canal.

-

Looking at the end of the canal. Guard Lock 8 is on the left side at the end. Highway bridge in background is I-68.

-

Looking at Guard Lock 8 today. Red brick building behind highway is the Canal Place museum and the Western Maryland Railroad Station.

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |