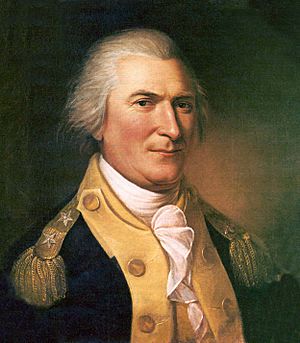

Charles Scott (governor) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Charles Scott

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 4th Governor of Kentucky | |

| In office September 1, 1808 – August 24, 1812 |

|

| Lieutenant | Gabriel Slaughter |

| Preceded by | Christopher Greenup |

| Succeeded by | Isaac Shelby |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 1739 Goochland County, Colony of Virginia, British America (now Powhatan County, Virginia) |

| Died | October 22, 1813 (aged 74) Clark County, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Resting place | Frankfort Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican |

| Spouses |

|

| Relations |

|

| Occupation | Farmer, miller, soldier, politician |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Branch/service |

|

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | Major general |

| Unit |

|

| Commands |

|

| Battles/wars | |

Charles Scott (born April 1739 – died October 22, 1813) was an American military officer and politician. He served as the fourth governor of Kentucky from 1808 to 1812.

Scott joined the military in 1755 and fought in the French and Indian War. He became a captain quickly. When the American Revolution began in 1775, he returned to service. He was promoted to colonel in 1776 and led the 5th Virginia Regiment. His regiment fought with George Washington in New Jersey. Scott was also Washington's chief of intelligence.

Later, he fought in the southern part of the Revolutionary War. He was captured when Charleston, South Carolina, surrendered in 1780. After being released, he helped recruit soldiers until the war ended in 1783.

After the war, Scott moved to Kentucky in 1787. He helped protect settlers from Native American raids. He became a brigadier general in the Virginia militia. He led a successful raid against Native American villages in 1791. After Kentucky became a state, he became a major general in the Kentucky militia. He fought alongside General Anthony Wayne in the Northwest Indian War, including the important Battle of Fallen Timbers.

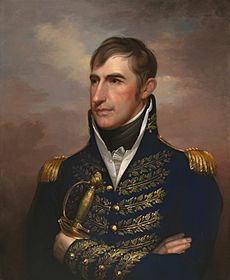

Scott ran for governor in 1808 and won easily. During his time as governor, he focused on the growing problems between the United States and Great Britain, which led to the War of 1812. He made a popular decision to appoint William Henry Harrison as a major general in the Kentucky militia. After his term, Scott's health declined, and he died in 1813. Scott County, Kentucky, and Scott County, Indiana, are named after him.

Contents

Early Life and Military Beginnings

Charles Scott was born in April 1739 in what is now Powhatan County, Virginia. His father, Samuel Scott, was a farmer and a member of the Virginia government. Charles had little formal schooling.

When his father died in 1755, Charles joined the Virginia Regiment. This was during the early part of the French and Indian War. He quickly became known as a skilled scout and woodsman. He rose through the ranks, becoming a corporal and then a sergeant.

Scott spent time at different forts, doing scouting and escort missions. He was part of the Forbes Expedition that captured Fort Duquesne in 1758. George Washington promoted him to ensign (a junior officer rank).

In 1760, Scott became a captain. He was part of an expedition against the Cherokee people. This expedition was successful. Scott left the army sometime before 1762.

Life as a Farmer and Family

Before 1762, Scott's older brother, John, died. This meant Charles inherited his father's land near the James River. He settled on this farm by late 1761.

On February 25, 1762, he married Frances Sweeney. They had four boys and four or five girls. Scott worked on his farm, growing tobacco and milling flour. In 1766, he became a captain in the local militia.

Fighting in the Revolutionary War

As the American Revolution began in 1775, Scott gathered a group of volunteers. This was the first group from south of the James River to join the Revolution. They helped drive Lord Dunmore, the British governor, out of Virginia.

In August 1775, Scott became a lieutenant colonel in the 2nd Virginia Regiment. His younger brother, Joseph, was also in this regiment. In December, Scott and 150 men helped defend a crossing point at the Battle of Great Bridge. They played a key role in stopping the British advance.

In February 1776, Scott's regiment joined the Continental Army. In August, he was promoted to colonel and given command of the 5th Virginia Regiment. They joined George Washington in New Jersey.

Scott's 5th Virginia Regiment fought in the colonial victory at the Battle of Trenton in December 1776. They also helped slow the British advance at the Battle of the Assunpink Creek in January 1777. Scott was praised for his bravery. He led raids against British groups looking for food.

Philadelphia Campaign

In April 1777, Scott was promoted to brigadier general. He returned to Washington's army in May. His brigade was part of a larger division.

At the Battle of Brandywine in September 1777, Scott's brigade fought hard but had to retreat. Scott strongly pushed for an attack on the British at Germantown. Washington agreed, and on October 4, 1777, Scott's brigade attacked. The battle was confusing due to heavy smoke, and the colonial forces retreated.

After this defeat, Washington's army camped for the winter at Valley Forge. Scott stayed nearby and inspected his brigade daily. He returned to his farm for a short break in March 1778.

In June 1778, Scott led 1,500 light infantrymen to bother British forces marching across New Jersey. This led to the Battle of Monmouth on June 28. During the battle, Scott's men retreated, which caused problems for the American attack.

After the Battle of Monmouth, Scott was given command of a new light infantry group. He also became Washington's chief of intelligence. He led scouting missions from their base in New York. He was sent home in November 1778.

Service in the South and Capture

In March 1779, Washington ordered Scott to recruit volunteers in Virginia. These new soldiers were to join General Benjamin Lincoln in South Carolina. The British were planning an invasion from the south.

Scott faced difficulties recruiting enough men. Finally, in October 1779, he sent troops to Lincoln in South Carolina. In February 1780, more men arrived at Scott's camp in Virginia.

On March 30, 1780, Scott arrived in Charleston, South Carolina. The British were attacking the city. He was captured when the city surrendered on May 12, 1780. He was held as a prisoner of war.

Scott was released in March 1781 due to poor health. In July 1782, he was officially exchanged for a British officer, ending his parole. Washington ordered him to help recruit more soldiers in Virginia. Recruiting stopped in March 1783 when peace talks began. Scott was promoted to major general on September 30, 1783, just before leaving the army.

Moving to Kentucky and Early Politics

After the war, Scott became interested in Kentucky. He visited in 1785 and began planning to move there. He settled near Versailles, Kentucky, in 1787. He built a log cabin and a tobacco warehouse.

In June 1787, his son, Samuel, was killed by Shawnee warriors while crossing the Ohio River. Scott watched helplessly. This event made him determined to fight against Native American raids.

Scott focused on building up his settlement, known as Scott's Landing. He sold land lots there. He also served as a tobacco inspector.

Scott supported the idea of Kentucky becoming a separate state from Virginia. He represented Woodford County in the Virginia House of Delegates for one term.

Northwest Indian War Campaigns

As tensions grew between settlers and Native Americans in the Northwest Territory, Scott led volunteers in raids. In April 1790, he joined Josiah Harmar in a raid against Native Americans in Ohio. This expedition did not achieve much. Scott's son, Merritt, was killed in a later expedition led by Harmar, which was also a failure.

In December 1790, Scott was appointed brigadier general in the Virginia militia. He was given command of the Kentucky District. He oversaw outposts along the Ohio River.

The Blackberry Campaign

Washington ordered Scott to lead raids in mid-1791. These raids would keep the enemy busy while a larger invasion force was gathered. Scott asked for volunteers to meet in Frankfort, Kentucky, on May 15, 1791. Many Kentuckians volunteered.

Scott's men left Fort Washington on May 24. They marched toward Native American settlements near present-day Lafayette, Indiana. The journey was difficult, and their supplies spoiled. They ate blackberries, which gave the expedition its nickname, the "Blackberry Campaign."

On June 1, they reached the village of Ouiatenon. The residents fled across the Wabash River. Scott's men burned the villages and crops. They also attacked another settlement called Kethtippecannunk.

Scott's men killed 38 Native Americans and took 57 prisoners. Only two of Scott's men died during the campaign. The expedition ended, and the men returned to Kentucky by June 16.

St. Clair's Expedition and Aftermath

Scott's campaign was well-received. However, the main invasion led by Arthur St. Clair was a disaster. St. Clair was not popular in Kentucky, and many officers, including Scott, were reluctant to serve under him.

St. Clair's force was attacked on November 4, 1791, by a combined group of Miami and Canadians. This event is known as St. Clair's Defeat. Many of St. Clair's men were killed or captured. The Kentucky militiamen scattered, and their leader, Colonel Oldham, was killed. Kentuckians blamed St. Clair for the failure.

After this defeat, Washington created the Legion of the United States to fight the Native Americans. General Anthony Wayne was chosen to lead it. In June 1792, after Kentucky became a state, Scott was made a major general in the state militia. He commanded the 2nd Division.

Wayne asked Scott's men to join his force. Scott agreed. In October 1793, Scott joined Wayne with about 1,000 men. Many of Scott's men deserted because they did not want to fight so close to winter.

Over the winter, relations improved between Wayne and the Kentuckians. Wayne built Fort Recovery at the site of St. Clair's defeat. This was a blow to the Native Americans and popular with Kentuckians. Scott defended Wayne's reputation.

In July 1794, Scott joined Wayne with 1,500 militiamen. They marched quickly and captured the Native American town of Grand Glaize. Scott named the new fort built there Fort Defiance, saying, "I defy the English, Indians, and all the devils in hell to take it."

On August 20, 1794, Scott's men fought in the Battle of Fallen Timbers. Wayne's forces won a decisive victory. After the battle, Scott's volunteers conducted raids and transported supplies. They were discharged on October 13, 1794. The Treaty of Greenville officially ended the war in 1795.

Later Political Career

After the war, Scott continued to serve as a major general in the state militia until 1799. His military heroism made him popular, and he became interested in politics. He joined the Democratic-Republican Party. In 1800 and 1804, he was chosen as a presidential elector and voted for Thomas Jefferson.

In 1803, Scott helped choose a site for a new fort in Kentucky. He recommended a site in Newport, Kentucky, which was accepted.

Scott faced personal losses. His sons Daniel and Charles Jr. died. His wife, Frances, died on October 6, 1804. He then moved in with his daughter and son-in-law in Lexington. He sold his farm in 1805.

On July 25, 1807, Scott remarried to Judith Cary (Bell) Gist. They moved to her family's plantation, Canewood.

Gubernatorial Election of 1808

Scott decided to run for governor in 1808. Other candidates included John Allen and Green Clay. Scott's campaign was managed by his stepson-in-law, Jesse Bledsoe.

Allen and Clay faced challenges. Allen had connections to Aaron Burr, which some people questioned. Clay was supported by settlers who owed money. Scott, as a senior Revolutionary War officer, was popular with veterans.

Scott won the election with 22,050 votes. Allen received 8,430 votes, and Clay received 5,516 votes.

Governor of Kentucky

One of Scott's first actions as governor was appointing Jesse Bledsoe as Secretary of State. Early in his term, Scott was injured in a fall on the icy steps of the governor's mansion. This injury left him needing crutches for the rest of his life. He relied heavily on Bledsoe for official duties.

Scott often disagreed with the state legislature. He wanted higher salaries for public officials and stronger punishments for criminals. He also wanted to keep taxes low. The legislature often ignored his ideas. He vetoed three bills, but the legislature overrode all of them.

During Scott's time as governor, tensions grew between the U.S. and Great Britain. Many Kentuckians wanted war with Britain. Scott believed a peaceful solution was unlikely.

In September 1811, William Henry Harrison, then governor of Indiana Territory, visited Kentucky to recruit soldiers. Although Harrison did not ask Scott for permission, Scott supported him.

In November 1811, news arrived of a Kentucky attorney general's death at the Battle of Tippecanoe. This increased calls for war. Scott encouraged support for the war effort. By July 1812, Kentucky had met its quota of 5,500 volunteers.

On August 25, 1812, Scott's last day in office, he appointed Harrison as a major general in the Kentucky militia. This appointment was popular in Kentucky and helped Harrison become the supreme commander of the Army of the Northwest.

Death and Legacy

After his term, Scott retired to his Canewood estate. His health quickly declined. He died on October 22, 1813. At the time of his death, he was one of the last surviving generals of the Revolutionary War.

His remains were later moved to Frankfort Cemetery in 1854. Scott County, Kentucky, and Scott County, Indiana, are named in his honor. The cities of Scottsville, Kentucky, and Scottsville, Virginia, are also named after him.

Images for kids

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |