Josiah Harmar facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Josiah Harmar

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | November 10, 1753 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Died | August 20, 1813 (aged 59) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Buried |

Saint James of Kingsessing Churchyard,

Philadelphia |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1775–1783, 1784–1792 |

| Rank | Lieutenant Colonel Brevet Brigadier General |

| Commands held | First American Regiment |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War Northwest Indian War |

Josiah Harmar (November 10, 1753 – August 20, 1813) was an important officer in the United States Army. He served during the American Revolutionary War and the Northwest Indian War. For over six years, from 1784 to 1791, he was the highest-ranking officer in the U.S. Army.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Josiah Harmar was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He went to a school run by the Quakers.

Serving in the American Revolution

Harmar began his military career in 1775. He became a captain in the army during the American Revolutionary War. His first battle was the Battle of Quebec in Canada.

He served under famous generals like George Washington and Henry Lee. Harmar was with Washington's troops during the difficult winter of 1777–78 at Valley Forge. George Washington thought highly of Harmar. He called him "one of the best officers in the Army."

By the end of the war, Harmar was a lieutenant colonel. He worked for General Nathanael Greene in the South. In 1784, Congress chose him to deliver the signed Treaty of Paris to Benjamin Franklin in Paris, France. While in France, Harmar met King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette at the Palace of Versailles. He was introduced by the Marquis de Lafayette. His time in Paris was expensive, so he needed to continue his military career.

In 1783, Harmar became a founding member of the Pennsylvania Society of the Cincinnati. This was a group for officers who fought in the Revolutionary War. He was the Society's first secretary for two years. Harmar married Sarah C. Jenkins in Philadelphia in October 1784.

Protecting the Northwest Territory

In the 1780s, many Americans wanted to move to the "Old Northwest." This area is now known as the Midwest. Native American tribes lived there and wanted to protect their lands. They were supported by the British, who still had fur-trading forts in the area.

After the Revolutionary War, the United States had almost no army. In 1784, Congress decided to create a new federal regiment. This was called the First American Regiment. It had about 700 men. Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut helped pay for it.

Josiah Harmar was chosen to lead this new regiment. He was known for being a strict leader. He wanted his soldiers to be very disciplined and professional. Harmar believed in rigorous training, like the Prussian style. He thought this would turn new recruits into strong soldiers.

In 1784, Harmar moved his command to Fort McIntosh. He was the highest-ranking officer in the U.S. Army from 1784 to 1791. Harmar was impressed by the rich land of the Northwest. He wrote about the large fish and wild strawberries.

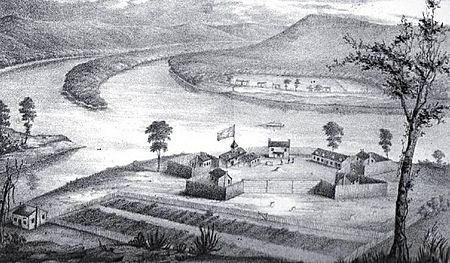

Harmar signed the Treaty of Fort McIntosh in January 1785. This treaty gave land in what is now southeastern Ohio to the United States. He also ordered the building of Fort Harmar in 1785. This fort was near what is now Marietta, Ohio.

Many American settlers started moving into the Old Northwest illegally. In March 1785, Congress ordered Harmar to remove these settlers. He described this as a difficult task. He asked Congress to survey and sell the land properly. This would prevent "lawless bands" from taking over.

In October 1785, Harmar founded Fort Harmar. This fort protected land surveyors. These surveyors were mapping out the land. Harmar also supervised the building of Fort Steuben. This fort was near present-day Steubenville, Ohio.

In July 1787, Harmar was promoted to brigadier general. He visited Vincennes, a French-Canadian town. He told the people that the area was now part of the United States. He also met with several Native American chiefs. He wanted to show them the power of the U.S. government. He also expressed the government's wish for peace.

In April 1788, Harmar welcomed Rufus Putnam. Putnam founded the village of Marietta next to Fort Harmar. Harmar reported that many settlers were moving into the Northwest. He celebrated the Fourth of July in Marietta with a parade. His wife and son joined him at Fort Harmar.

As more settlers arrived, there was more conflict between settlers and Native Americans. Harmar and Governor Arthur St. Clair began talks with Native American leaders in January 1789. These talks led to the Treaty of Fort Harmar. More land was given to the United States. However, some tribes, like the Miami and Shawnee, did not attend. Harmar predicted this would lead to war.

In 1789, Harmar directed the building of Fort Washington. This fort was on the Ohio River, in modern-day Cincinnati. It was built to protect southern settlements.

Harmar often disagreed with Henry Knox, the Secretary of War. Knox believed state militias should be the main defense. He also had a personal interest in selling Native American lands. Harmar thought the militias were not strong enough. He believed a well-trained federal army was needed. He complained that many militiamen were "hardly able to bear arms." They were often "old, infirm men and young boys."

Campaign Against the Miamis

In 1790, Harmar led an expedition against Native Americans in the Northwest Territory. The British still supplied guns to the Native Americans. This was to keep Americans out of the area. Secretary Knox ordered Harmar to destroy Native American villages.

Preparing for the Campaign

Many militiamen did not want to serve under Harmar. Some hired "substitutes" to go in their place. These substitutes were often not experienced fighters. Harmar had only a few weeks to train the militias.

Harmar's plan was to take 1,300 militiamen and 353 regular soldiers. They would attack Kekionga (modern Fort Wayne, Indiana). This was the capital of the Miami Indians. Another group of militia would create a distraction.

The Campaign Begins

Harmar marched his men in a formation that was not suited for the wilderness. This made their progress slow. He hoped to capture British and French-Canadian fur traders. He called them the "real villains" for supplying the Miami.

The Native American leader, Little Turtle, avoided direct battle. Instead, the Native Americans burned their villages and retreated. On October 15, 1790, Harmar's forces reached Kekionga. They found the town empty and burning. Harmar believed he had won the war without a fight. However, the Miami later stole many of Harmar's horses. This made his force less mobile.

On October 19, Harmar sent a group of 180 men to find the Miami. This group included 30 U.S. Army soldiers. Many militiamen left the ranks and returned to camp. The remaining men were ambushed by Little Turtle's forces. Most of the militiamen fled. The U.S. Army regulars fought bravely but were overwhelmed.

Harmar was shocked by this defeat. He threatened to use cannons on any militia that retreated again. The Native Americans watched Harmar's camp. They decided not to attack directly because it would cost too many lives.

On October 20, Harmar's army burned and destroyed crops and buildings around Kekionga. Harmar believed this would weaken the Miami. On October 21, Harmar ordered his men to return to Fort Washington.

Harmar's Defeat

Later that day, Harmar sent 400 men back to Kekionga. This force included 60 U.S. Army soldiers and 340 militiamen. They were led by Major John Wyllys. The plan was to surprise any Native Americans returning to the town.

The American force split into three groups. However, there was poor coordination. The militia groups fired their weapons too early. This alerted the Native Americans. Little Turtle had set an ambush at a ford in the Maumee River. As the Americans crossed, they were attacked. Many American soldiers were killed.

The Americans pursued the Native Americans, thinking they were retreating. But Little Turtle had set another ambush. In a cornfield, a large number of Miami warriors attacked. This was known as the "Battle of the Pumpkin Field." The Americans fought hand-to-hand with bayonets and swords against tomahawks and spears. Major Wyllys and many soldiers were killed.

When Harmar learned of the terrible defeat, he decided to retreat. He did not try to retrieve or bury the American dead. This was unusual for the U.S. Army. Harmar complained that the militia was "ungovernable." He ordered his regulars to keep bayonets fixed on the militia to keep them in line.

Aftermath of the Campaign

When Harmar returned to Fort Washington, the public was angry about his defeat. Harmar claimed he had won a great victory. But militiamen told newspapers the truth. They accused Harmar of being cowardly and incompetent.

Historians say Harmar's expedition was poorly planned. He did not understand frontier warfare. He should have known that Native Americans preferred ambushes. His refusal to bury the dead also hurt his reputation. The American dead at Kekionga were not buried until 1794.

Harmar was removed from command. General Arthur St. Clair replaced him. St. Clair later suffered an even worse defeat.

Court-Martial Inquiry

Harmar asked for a court-martial inquiry to clear his name. He was accused of negligence. The court found him innocent of the charges.

Later Life and Legacy

After resigning from the Army in January 1792, Harmar returned to Pennsylvania. He served as the state's adjutant general from 1793 to 1799. Harmar was well-liked in Philadelphia in his later years. People described him as friendly. He was tall and well-built, with blue eyes.

Harmar died near Philadelphia in 1813. He is buried at the Episcopal Church of St. James Kingsessing. He had a daughter, Eliza Harmar Thomas, and two sons, Josiah Harmar and William Harmar.

Images for kids