Kekionga facts for kids

Kekionga was a very important village for the Miami people, a Native American tribe. Its name means "blackberry bush." It was also known as Kiskakon or Pacan's Village. Kekionga was located where the Saint Joseph and Saint Marys rivers meet to form the Maumee River. This area is in what is now Indiana.

Kekionga was a key spot because it was on an important travel route. This route connected Lake Erie to the Wabash River and Mississippi River. Because of its location, the French, British, and Americans all wanted to control it. They built trading posts and forts there over many years. After the War of 1812, the American town of Fort Wayne, Indiana grew up around the American fort built at this site.

Contents

History of Kekionga

Kekionga was a large village of the Miami people when Europeans first arrived. Many different groups of indigenous peoples had lived in this area for a long time.

The village became a very important trading center for Europeans. This was because it was on a six-mile path, called a portage. This portage connected the Maumee River and the Little River. This link was a shortcut between Lake Erie and the Wabash River, which then led to the Mississippi River.

At first, trading with Europeans was good for the Miami people. These traders were mostly Canadiens from Quebec. A French leader named Jean Baptiste Bissot, Sieur de Vincennes set up a trading post and a fort near Kekionga. He and the Miami people became good friends.

Kekionga was a main village for the Miami for many years. It had a large meeting house where important tribal councils were held. However, a serious illness called smallpox spread in Kekionga in 1733. People had to leave the village for a year because of it. Later, a Miami chief named Little Turtle called Kekionga "that glorious gate." He said it was where all important messages passed from north to south and east to west.

Changing Control

British traders wanted to expand their business. They convinced some Miami to trade with them, even though it went against an agreement called the Treaty of Utrecht (1713). In 1749, a pro-British Miami chief named La Demoiselle left Kekionga. He started an English trading village called Pickawillany, which grew quickly.

By 1751, fighting broke out between Miami villages that supported the French and those that supported the British. French leaders tried to get the Miami to return to Kekionga. This was because Kekionga was closer to their main base in Detroit. In 1752, the French built a new fort at Kekionga. That same year, another smallpox outbreak happened, and a pro-French chief named Cold Foot died. When the French-allied Three Fires Confederacy destroyed Pickawillany, most of the Miami who survived went back to Kekionga.

After the French and Indian War (1756-1763), France lost Canada to the British. The Miami of Kekionga then joined Pontiac's Rebellion in 1763. They captured the British fort and killed two officers. The next year, Pacanne became the village chief. He saved the life of a British captain, Thomas Morris, and sent him back to Detroit. By 1765, Kekionga had accepted British rule. A British official, George Croghan, described the village as having 40 to 50 Native American cabins and about 9 or 10 French houses.

Kekionga in the Northwest Territory

In 1780, during the American Revolutionary War, Kekionga was attacked. A group of French colonials led by Colonel Augustin de la Balme raided the village. They planned to take Detroit from the British. However, a Miami force led by Chief Little Turtle defeated the French group.

Even after the American Revolution, the Miami and traders in Kekionga remained connected to the British. This was true even though the British gave up their claims to the Northwest Territory to the United States in the Treaty of Paris (1783).

In 1790, the Canadian Governor Guy Carleton warned that losing Kekionga would hurt Detroit's economy. He said Kekionga produced many animal furs each year, which were very valuable.

During the winter of 1789-1790, traders Henry Hay and John Kinzie stayed in Kekionga. Hay wrote in his journal about their daily lives, including parties and weekly church services. They were popular because Hay played the flute and Kinzie played the fiddle. They often spoke with chiefs like Pacanne, Little Turtle, Blue Jacket, and Le Gris.

The new American President, George Washington, wanted a strong U.S. fort at Kekionga. This Native American city was important for British trade. It also protected the key portage between the Great Lakes Basin and the Mississippi watershed. However, the Secretary of War, Henry Knox, worried that building a fort there would anger the Native Americans.

In 1790, U.S. General Josiah Harmar was ordered to attack Kekionga. His army found seven different villages there, known as "the Miami Towns." These villages also had many Shawnee and Delaware people. The people of Kekionga knew the army was coming. Most of them left the area, taking their food with them. Traders gave their weapons and ammunition to the Miami defenders before leaving for Fort Detroit.

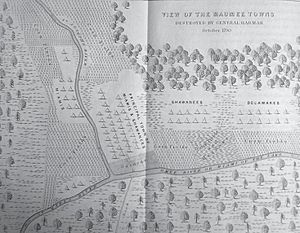

Major Ebenezer Denny, an American officer, drew a map of Kekionga in 1790. It showed eight villages surrounded by 500 acres of cornfields. Denny described the area as having "several little towns on both branches" of the rivers. He also noted "several tolerable good log houses" used by British traders, gardens, fruit trees, and "vast fields of corn."

The U.S. army burned some villages and food supplies. But they had to retreat after many soldiers were killed in battles with forces led by Little Turtle. The Miami's victories made people in Kekionga feel stronger against the U.S. Because of this, Henry Knox decided a U.S. fort had to be built there. He ordered Governor Arthur St. Clair to attack Kekionga. However, St. Clair's army was stopped before they reached Kekionga. This became the Native Americans' greatest victory over U.S. forces.

Kekionga's Decline

After the attacks by Harmar in 1790, the Native American alliance moved their main center away from Kekionga.

In 1794, American General Anthony Wayne led his well-trained army toward Kekionga. But he turned and marched toward the British-held Fort Miami near what is now Toledo, Ohio. After General Wayne won the Battle of Fallen Timbers, Kekionga became less important to the Miami.

Wayne's army arrived at Kekionga on September 17, 1794. Wayne himself chose the spot for the new U.S. fort, which was named after him. It was finished by October 17. Even though the Miami objected, they lost control of the important portage in the Treaty of Greenville (1795). This was because a law called the Northwest Ordinance said important portages in the region had to be open for everyone to use. At that time, the Miami said the portage earned them $100 every day.

After Fort Wayne was built, Kekionga's importance to the Miami slowly faded. Another Miami village at the Forks of the Wabash (modern Huntington, Indiana) became more important. Even with the strong U.S. presence and the loss of money from the portage, the Miami kept control of Kekionga through the War of 1812. But after the war, in the Treaty of Ghent (1814), they were forced to give up this land. This was a punishment for not supporting the United States in the war. The area was then developed into the city of Fort Wayne, Indiana between 1819 and 1823.

The old name, Kekionga, was used for one of the first professional baseball teams, the Fort Wayne Kekiongas. It also appears on Fort Wayne's city seal today.

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |