Harmar campaign facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Harmar campaign |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Northwest Indian War | |||||||

General Josiah Harmar |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

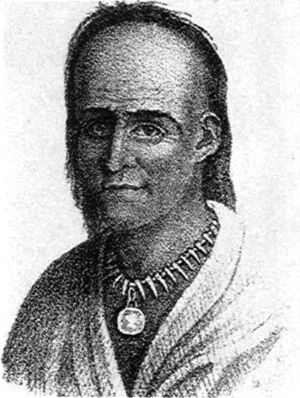

| Little Turtle (Miami) Blue Jacket (Shawnee) Le Gris (Miami) |

Josiah Harmar John Hardin |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| about 1,050 warriors | 320 regulars 1,100 militia |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| about 120-150 killed or wounded | 262 killed 106 wounded |

||||||

The Harmar campaign was a military operation in the autumn of 1790. The United States Army wanted to stop attacks from Native American nations in the Northwest Territory. These groups were part of the Northwestern Confederacy. General Josiah Harmar led the American forces.

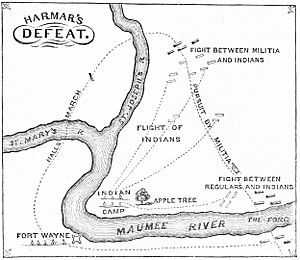

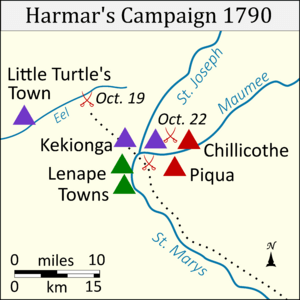

This campaign was a major event in the Northwest Indian War. It ended with several battles from October 19–21, 1790. These fights happened near the Miami villages of Kekionga, which is now Fort Wayne, Indiana. The Native American forces won all these battles. Because of this, the campaign is often called Harmar's Defeat.

Contents

Why the Harmar Campaign Happened

From 1784 to 1789, there was a lot of fighting. American settlers were moving into lands where the Shawnee and Miami Indians lived. This area was in Kentucky and along the Ohio River. About 1,500 settlers were killed by Native Americans during this time. Before the American Revolutionary War, the British had tried to keep this land for Native Americans. But after the United States became independent, this land became the Northwest Territory. American settlers were very eager to move there.

United States Secretary of War Henry Knox (a top government official) first tried to avoid military action. He worried it would cause more conflict. In 1789, President George Washington asked Arthur St. Clair. St. Clair was the governor of the Northwest Territory. Washington wanted to know if the Native Americans wanted war or peace. St. Clair decided they "wanted war." He then called for soldiers to gather at Fort Washington (now Cincinnati, Ohio) and Vincennes, Indiana.

President Washington and Henry Knox ordered General Harmar to lead these forces. Their mission was to punish the Shawnee and Miami for attacks. They also hoped to stop future attacks on the frontier. In early 1790, the U.S. sent messages to discuss peace. But these talks did not go well. Native American attacks continued through the summer. Just before the campaign started, some Miami and Potawatomi leaders came to Vincennes to talk peace. Major Jean François Hamtramck, the commander there, sent them away. He told them they must return all prisoners first.

The main goal of Harmar's campaign was to destroy Native American villages. These villages were near Kekionga. Kekionga was a large Miami town. The St. Joseph and St. Mary's rivers meet there to form the Maumee River. St. Clair and Harmar also planned to build a fort there. But President Washington decided a fort would be too risky and too costly. British forces still held Fort Detroit. This was against the Treaty of Paris. St. Clair wrote to the British at Fort Detroit. He told them the expedition was only against Native American tribes. He hoped the British would not get involved.

The Campaign Begins

General Harmar gathered his army. He had 320 regular soldiers from the First American Regiment. These were split into two groups. He also had 1,133 militia (citizen soldiers) from Kentucky and Pennsylvania. In total, he had 1,453 men. The force also had three cannons pulled by horses. The campaign started from Fort Washington on October 7, 1790. General Harmar began marching north along the Great Miami River.

A smaller group, led by Major Hamtramck, marched north from Vincennes. Hamtramck had 330 soldiers and militia. His job was to distract the Wabash Native Americans. Then he was supposed to join Harmar for the main attack. Hamtramck's group burned a few villages over 11 days. But his militia refused to keep going. So, Hamtramck returned to Vincennes instead of joining Harmar. By October 13, Harmar was close to Kekionga. That day, Kentucky patrols captured a Shawnee scout. The scout said the Miami and Shawnee had decided to leave their towns instead of fighting.

The people of Kekionga and nearby villages had little time to get ready. They decided to leave their homes. Before dawn on October 15, Harmar sent 600 men under Colonel John Hardin. He hoped to surprise the Native Americans at Kekionga. But when Hardin's group arrived, the village was empty. They burned the village and any supplies they found. Then they camped south of the destroyed town.

Harmar reached other Miami villages near Kekionga on October 17. The Miami had been warned about the attack. They had left their villages, taking as much food as they could. Some British traders lived among the Miami. They fled to Fort Detroit with their families and goods. They had given all their weapons and ammunition to Miami warriors. The Miami knew a lot about Harmar's army. The Americans took the food the Miami had left behind. On the morning of October 18, a patrol rode toward the Kickapoo towns. They were looking for people who had left their homes. The patrol found and killed two Native Americans. A patrol member got lost and found a large group of warriors. But the patrol could not find them again before returning to camp. Colonel Hardin then got permission to lead a similar patrol the next day.

Major Battles

Hardin's First Battle

On October 19, Harmar moved his main army to the Shawnee town of Chillicothe. This town was two miles east of Kekionga on the Maumee River. Harmar sent out a scouting party led by Colonel Hardin. This group went south of modern Churubusco, Indiana. The force had 180 militia, a cavalry group, and 30 regular soldiers. Their goal was to find out how strong the Native Americans were. They also planned to attack the village of Chief Le Gris. The group got close to Kekionga. They saw a Native American on horseback, who rode away on a small trail. Hardin ordered his men to chase him. But he sent some cavalry back to get another company of soldiers. The Native American was a decoy. He led Hardin into a swampy area. This area was bordered by fallen trees and the Eel River. Horses could not easily move or retreat there.

The militia were spread out when Hardin rode into a meadow. This meadow was near the village of Little Turtle. Little Turtle had left shiny objects and goods there. The militia gathered around a fire and started picking up the items. Then they were attacked by surprise. The first shots came from their right. Several militia members were killed. The U.S. force moved to their left. There, they were met with more close-range gunfire.

Captain Armstrong formed a line with 30 regular soldiers and 8 militia. But most of the American force ran away. Another group of soldiers refused to join the fight. After the U.S. line fired one shot, the Native American force charged. This force was mostly Miami, with some Shawnee and Potawatomi. They used handheld weapons. Only 8 of the 30 regular soldiers survived. Captain Armstrong hid in the marsh. Ensign Asa Hartshorne hid under a log. Major Fontaine met the fleeing militia and the missing company. They formed a new line, and Colonel Hardin joined them. They saw a few Miami warriors who stopped chasing. They held the line until they thought no more militia were running away. Then they went back to the main camp. They estimated that 40 militia were killed and 12 were wounded.

Captain Armstrong arrived in camp the next morning. He blamed Hardin and the militia for the defeat. He said only about 100 Native Americans were involved. This was about the number of warriors from Kekionga and Le Gris' village. General Harmar refused Hardin's request to go back to the battle site. Instead, he said the army must finish destroying villages. Then they would prepare to return to Fort Washington. The battle on October 19 is sometimes called Hardin's defeat.

The Battle of Kekionga

On October 21, Harmar announced that their mission was done. He ordered his forces to start going back to Fort Washington. They marched about eight miles and camped at the same spot they had used on October 16. That evening, scouts came to camp. They reported that about 120 Native Americans had returned to Kekionga. The number might have been higher. Shawnee, Miami, Lenape, Odawa, and Sauk warriors were coming into the town.

The American soldiers wanted to get revenge for their earlier losses. They also hoped to stop Native Americans from attacking them on their way back. So, Harmar put together a force under Major Wyllys. This group had 60 regular soldiers, 40 mounted soldiers, and 400 militia. Colonel Hardin and Major Horatio Hall led the militia. Wyllys' force left at 2:00 AM on October 22. At dawn, they stopped by the Maumee River. They split into four groups. Hardin and Hall went west, south of the Native American towns. They planned to wait on the western bank of the St. Joseph River. Wyllys, Fontaine, and Major James McMullan crossed the Maumee. They planned to scare the Native Americans. This would make them cross the St. Joseph, where Hardin and Hall would be waiting.

The militia under Hardin and Hall found Native Americans as they approached their position. It is not clear who fired first. But the sound alerted those in Kekionga. Wyllys ordered a full attack. But warriors hiding on the opposite bank attacked while his force was crossing. Fontaine led a cavalry charge into the woods. He was killed. His men then retreated without a leader. Once Wyllys and McMullan regrouped, small groups of warriors bothered them. These warriors fired on the militia and then ran away. McMullan's militia chased them, moving north. This left the regular soldiers under Wyllys alone. After a short fight, they were trapped and forced to fight at close range. The results were as bad as on October 19. Survivors ran across the St. Joseph River to join Hardin's groups. The Shawnee and Miami attacked Hardin from three sides. Hardin waited for help from Harmar. He defended his position for over three hours. Finally, he had to fall back to join the rest of the army.

Meanwhile, Hall crossed the St. Joseph to the north. He joined up with McMullan. They marched together to Kekionga. They got ready for another fight. But it was quiet, so they returned to the main army under General Harmar. Both Hardin and Hall met with Kentucky Major James Ray. Ray was only 3 miles from camp. Harmar had sent Ray to help in the battle. But Ray only had 30 men who were willing to go. In this battle, 180 American men were killed or wounded. The army reported 129 men killed (14 officers, including Wyllys and Fontaine, and 115 enlisted men). Also, 94 were wounded (including 50 regular soldiers). Estimates of Native American casualties range from 120 to 150.

What Happened Next

After so many losses, General Harmar decided he could not attack again. Winter was coming, which also threatened his army. Militia soldiers left, and horses starved. The army reached Fort Washington on November 3. Native American leaders thought about a final attack on Harmar's retreating forces. But the Odawa reportedly went home. They saw a lunar eclipse and thought it was a sign not to attack. Their homes and food were stolen or destroyed. So, many people had to rely on other villages to survive that winter. Important Miami cultural items were also lost. These were never recovered. After the attacks, the Native American confederacy moved their main center away from Kekionga to the Auglaize River.

Harmar's losses were the worst defeat for U.S. forces by Native Americans at that time. Later, St. Clair's defeat in 1791 and the Battle of the Little Bighorn in the late 1800s were even worse. Little Turtle became a hero among Native Americans. The Native Americans in the Northwest Territory felt stronger. They continued to fight against the United States. The campaign was supposed to bring peace. Instead, Harmar's defeat led to more attacks on U.S. settlements. These attacks were for revenge and to get back crops Harmar destroyed. These attacks included the Big Bottom massacre in January 1791 and the Siege of Dunlap's Station.

President Washington was very angry about the defeat. He worried about the cost and lack of success. He and St. Clair feared the defeat would make the confederacy stronger. Senator William Maclay said the government started a war without Congress's permission. He thought it might be an excuse to create a standing army. In December, General Von Steuben wrote to Alexander Hamilton. He was sad about the loss of Major Wyllys. He also worried about Major Hamtramck. He wrote, "This war is not over, it is only the Commencement of the Hostilities."

A court-martial (military trial) in 1791 found Harmar innocent of any wrongdoing. Despite the heavy losses, Harmar believed he had achieved his main goal. Five villages had been destroyed by people leaving or by his army. Tens of thousands of bushels of grain were taken or destroyed. However, John Cleves Symmes said the panic from the Native American victory would stop new settlers from moving to Ohio.

This campaign was the first time Miami leader Little Turtle and Shawnee leader Blue Jacket worked together in a full military operation. William Wells said Little Turtle led the defense against Hardin. Blue Jacket led the Shawnee, Buckongahelas the Delaware, and Egushawa the Odawa. Wells, who was Little Turtle's son-in-law, later said Little Turtle was in overall command. But others believed Blue Jacket was in charge. After learning of the defeats, Congress raised a second group of regular soldiers. But they later cut the soldiers' pay. The First Regiment was reduced to 299 soldiers. The new Second Regiment only got half the soldiers they were supposed to have. When Governor St. Clair led a similar expedition the next year, he had to call on the militia to get enough men.

Images for kids