Decatur House facts for kids

|

Decatur House

|

|

|

U.S. National Historic Landmark District

Contributing Property |

|

North side of Decatur House as restored 2006–2008.

|

|

| Location | 748 Jackson Pl., NW. Washington, D.C. |

|---|---|

| Area | < 1-acre (0.40 ha) |

| Built | 1818 |

| Architect | Benjamin Henry Latrobe |

| Architectural style | Federal |

| Part of | Lafayette Square Historic District (ID70000833) |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000858 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHL | December 19, 1960 |

| Designated NHLDCP | August 29, 1970 |

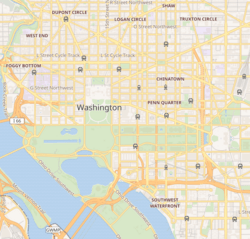

Decatur House is a historic house museum located at 748 Jackson Place in Washington, D.C.. This important building is named after its first owner, Stephen Decatur, a famous naval officer. Built in 1818, the house stands near Lafayette Square, just a short distance from the White House.

In 1836, new owners added a building behind the main house. This addition was partly used as living quarters for enslaved people. Until 1863, when the Emancipation Proclamation took effect, enslaved Black individuals were sometimes bought and sold in the house's backyard. Today, Decatur House is a museum. It also hosts the National Center for White House History, run by the White House Historical Association.

Contents

History of Decatur House

Decatur House is one of the oldest homes still standing in Washington, D.C. It is also one of only three houses left in the United States designed by the famous architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe. He was known for his neoclassical style, which means he used ideas from ancient Greek and Roman buildings.

Early Owners and Important Guests

The house was finished in 1818 for naval hero Stephen Decatur and his wife, Susan. It has a special location across Lafayette Square from the White House. After the Decaturs, several important people lived in the house. These included Henry Clay, Martin Van Buren, and Edward Livingston. They all rented the house while serving as the Secretary of State. This made Decatur House an unofficial home for the Secretary of State from 1827 to 1833.

Enslaved People at Decatur House

In 1836, John Gadsby, who was one of the wealthiest men in Washington D.C., moved into the house with his wife Providence. They brought enslaved people with them. The Gadsbys built a two-story building at the back of the property. This new building held the kitchen and served as living quarters for the people Gadsby had enslaved. Before this, these individuals lived in the main house. This back building is one of the few remaining examples of urban slave quarters. It is also rare physical proof that African Americans were held in slavery so close to the White House.

Later Residents and Civil War Use

After John Gadsby passed away, the house was rented to more important figures. These included Vice President George M. Dallas and publisher Joseph Gales. Congressmen John A. King and James G. King also lived there. Other residents included Representative William Appleton, Speaker of the House James Lawrence Orr, and Senator Judah P. Benjamin. During the American Civil War, the house was used as offices for the Army. After the war, it remained empty for six years.

Becoming a Museum Today

In 1872, Edward Fitzgerald Beale bought Decatur House. He was an explorer and rancher who later became a diplomat. Edward Beale's daughter-in-law, Marie, later gave Decatur House to the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 1956. The house was recognized as a U.S. National Historic Landmark in 1976.

Today, Decatur House is a museum located at 748 Jackson Place, N.W., near President's Park (Lafayette Park). The lower floor of the house is kept in the style of the early 1800s. The upper floor was updated in the early 1900s.

Because of its central location and the important people who lived there, the museum now shares many stories about African American history. One of these stories is about Charlotte Dupuy. In 1829, she sued her enslaver, Henry Clay, for her freedom and the freedom of her two children. Although she lost her court case at first, Clay eventually freed Charlotte and her daughter in 1840. He freed her son in 1844. The museum has a special exhibit that tells more about African American history up to 1965.