James G. Birney facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

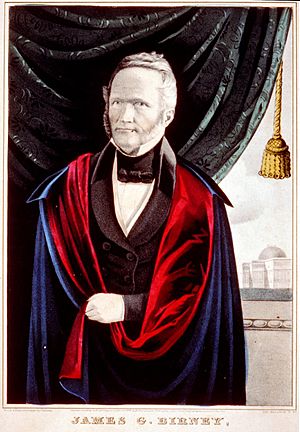

James G. Birney

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Personal details | |

| Born |

James Gillespie Birney

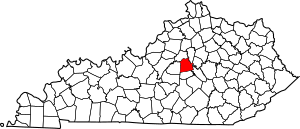

February 4, 1792 Danville, Virginia (now Kentucky), U.S. |

| Died | November 18, 1857 (aged 65) Perth Amboy, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican (before 1825) Liberty (1840–1848) |

| Spouses | Agatha McDowell Elizabeth Potts Fitzhugh |

| Children | Five Including |

| Parents | James G. Birney Martha Reed |

| Education | Transylvania University Princeton University (BA) |

| Signature | |

James Gillespie Birney (born February 4, 1792 – died November 18, 1857) was an American abolitionist, a person who wanted to end slavery. He was also a politician and a lawyer from Danville, Kentucky.

Birney started his life as a plantation owner who owned slaves. But he later changed his mind and became a strong opponent of slavery. He even started an anti-slavery newspaper called The Philanthropist. He was chosen twice to run for president by the Liberty Party, which was a political group focused on ending slavery.

After studying law at Princeton University, Birney became a lawyer in Danville. He was involved in politics, serving on the town council and in the Kentucky House of Representatives. Later, he moved to Madison County, Alabama, where he bought a cotton plantation and continued his political career in the Alabama House of Representatives. Eventually, he sold his plantation and became a very successful lawyer in Huntsville, Alabama.

During the 1820s, Birney became more and more concerned about slavery. He joined the American Colonization Society, which believed in sending African Americans to Africa. But he soon realized that this wasn't the right solution. He then began to demand that slavery be ended immediately. In 1835, he moved to Cincinnati and started his anti-slavery newspaper. He also joined the American Anti-Slavery Society, but he left because he didn't agree with their views on equal rights for women. Birney ran for president in 1840 and 1844 for the Liberty Party, trying to bring attention to the issue of slavery. In 1841, he moved to Michigan and helped create the town of Bay City, Michigan.

Contents

Early Life

James G. Birney was born into a wealthy family in Danville, Kentucky. His father, also named James G. Birney, owned slaves. James's mother, Martha Reed, died when he was only three years old. He and his sister were then raised by their aunt, who came from Ireland. His aunt was against slavery and refused to own slaves, which influenced young James.

Many of his family members, both from his father's and mother's side, lived nearby in Mercer County, Kentucky. Growing up, James saw different opinions about slavery. His father had tried to stop Kentucky from becoming a slave state. When that failed, he believed it was okay to own slaves as long as they were treated well. Other family members felt it was morally wrong to own slaves at all.

When James was six, he received his first slave, a boy named Michael, who was his age. However, throughout his youth, he was taught by teachers and friends who were against slavery. He remembered listening to sermons by a Baptist abolitionist named David Barrow, which he liked very much.

Education and Law Studies

At age eleven, James was sent to Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky. One of his teachers there, Robert Hamilton Bishop, was an early opponent of slavery in the state. Two years later, he returned home to attend a new school in Danville, where he was very good at science.

In 1808, when he was seventeen, James went to the College of New Jersey (which is now Princeton University). He studied political philosophy, logic, and moral philosophy. He became known as a skilled debater. He became good friends with a classmate named George M. Dallas. He also learned from the school's president, Samuel Stanhope Smith, who was somewhat against slavery. Another person who influenced his anti-slavery thinking was John McLean. James graduated from Princeton on September 26, 1810.

After graduating, he worked for Henry Clay's political campaign for a month. Then, he moved to Philadelphia to study law with Alexander J. Dallas, who was the father of his Princeton friend. James came from a wealthy family, so he had a horse carriage and always dressed well. He also made friends with members of the Quaker community, who were often against slavery. He stayed in Philadelphia for three years, until he passed his law exam and became a lawyer.

Starting His Law Career

In May 1814, Birney returned to his hometown of Danville to practice law. He became the lawyer for the local bank and handled different kinds of lawsuits. At this time, Kentucky's economy was struggling because of the War of 1812. To make enough money, Birney often worked as a claims adjuster.

Like his father, Birney joined the Freemasons and became a member of Danville's town council. This made him part of the town's important social group. On February 1, 1816, he married Agatha McDowell. They had 11 children, but only 6 lived to be adults. As wedding gifts, they received slaves from both his father and his father-in-law. At this time, Birney had not yet fully developed his strong anti-slavery views, so he accepted them. However, he later said that he never truly believed slavery was right.

Political Life in Kentucky

In 1815, Birney again helped Henry Clay in his successful campaign for U.S. Congress. He also campaigned for George Madison, who became the Kentucky Governor. George Madison was also his wife's uncle. At this time, Birney was part of the Democratic-Republican Party.

In 1816, at age twenty-four, Birney won a seat in the Kentucky Legislature, representing Mercer County. In 1817, the Kentucky Senate suggested a plan to work with Ohio and Indiana to create laws that would help capture and return runaway slaves from Kentucky. Birney strongly opposed this idea, and it was defeated. However, a similar plan was later passed despite his continued opposition. Feeling that he had little future in Kentucky politics, Birney decided to move to Alabama to start a new political career.

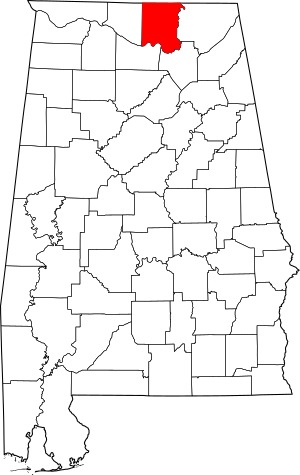

Moving to Alabama

In February 1818, Birney moved his family to Madison County, Alabama. He bought a cotton plantation and slaves, many of whom came with him from Kentucky. In 1819, Birney became a member of the Alabama House of Representatives for Madison County. While there, he helped create a law that would give slaves who were tried by a jury their own legal counsel. This law also prevented slave owners or their relatives from being on the jury. This, along with his opposition to Andrew Jackson becoming president, made it harder for him to achieve his political goals in Alabama. He didn't like Jackson because he thought he was too quick to anger and had even ordered the execution of two men.

By 1823, Birney was having many problems with his cotton plantation. He also had a habit of gambling on horse races, which he eventually stopped after losing a lot of money. He decided to move to Huntsville, Alabama, to practice law again. Most of his slaves stayed at the plantation, but he brought his servant Michael, Michael's wife, and their three children with him to Huntsville.

In Huntsville, Birney quickly became a respected lawyer. He was admitted to the Alabama bar association. With the help of John McKinley and other important people, Birney became the solicitor (a type of public prosecutor) for Alabama's Fifth District in 1823. By the end of that year, he closed his plantation and sold his slaves to a friend who was known for treating slaves kindly. After selling the plantation, he became financially stable. He bought a large piece of land and built a big brick house in Huntsville. Just like in Danville, he became a part of the important social group in his new town. His private law office also made him a lot of money.

By 1825, he was the richest lawyer in northern Alabama. He even partnered with another lawyer, Arthur F. Hopkins. The next year, he left his job as solicitor general to focus more on his private law career. Over the next few years, he often defended Black people in court. He also became a trustee for a private school and joined the Presbyterian Church. In 1828, he supported John Quincy Adams for president, believing Adams's ideas were good for the United States. He was very disappointed when Jackson won the election. However, he found other ways to help his community. In 1829, he was elected mayor of Huntsville, Alabama. This allowed him to work on improving public education and promoting temperance (avoiding alcohol).

Changing Views on Slavery

Birney's strong religious beliefs also made him think more deeply about slavery. He became interested in the American Colonization Society in 1826. In 1829, Henry Clay introduced him to Josiah Polk from the ACS, and Birney became an early supporter. He was curious about the idea of creating a colony in Liberia, Africa, for free Black people. In January 1830, he helped start a local chapter of the society in Huntsville, Alabama.

Later that year, he traveled to the East Coast to find professors for the University of Alabama. During his trip, he visited cities like Philadelphia, New York, and Boston. He was encouraged by seeing states where slavery was not allowed. Around this time, he also stopped supporting Henry Clay and the Democratic-Republican Party.

In 1831, Birney thought about moving to Illinois because he didn't want his children to grow up in a slave state. He often said he would free his remaining slaves—Michael, Michael's wife, and their three children—if he moved there. However, this move never happened. In 1832, the American Colonization Society offered him a job to travel around the South and promote their cause. He accepted and had some success, even helping to organize trips for settlers to Liberia. But as he tried to convince people to support colonization, he started to doubt if it was truly effective or if slavery could ever be acceptable. By 1832, he decided to return to Danville, Kentucky.

Becoming an Abolitionist

Birney's decision to stop supporting the American Colonization Society was very important. Many people, like Gerrit Smith, called it "celebrated." Birney had worked for the society, so he knew a lot about their efforts in the South.

In 1833, he read a paper from several Christian groups that disagreed with the American Colonization Society. Instead, they called for slavery to be ended immediately. This, along with his own experiences and studies, made Birney realize that slavery had to be abolished completely. Inspired by discussions with Theodore Dwight Weld, he freed his remaining slaves and officially declared himself an abolitionist in 1834.

The Abolitionist Newspaper

Birney decided to make Cincinnati his home base and connected with other abolitionists there. He worked to get support for publishing an anti-slavery newspaper. At that time, most newspapers in Cincinnati criticized abolitionism. One paper, The Daily Post, even suggested harming those who wrote anti-slavery articles.

However, the Cincinnati Daily Gazette, owned by Charles Hammond, became an ally. While Hammond didn't support equal rights for Black people, he did believe in freedom of the press and freedom of speech. He also disliked the idea of the South trying to make slavery legal in the North.

Birney's first plan was to publish his newspaper in Danville, Kentucky. But in August 1835, a large meeting of people in Danville warned him not to publish his anti-slavery paper. They told him he would face serious problems if he continued. So, in September, he moved to Cincinnati instead.

When Birney started publishing his weekly abolitionist newspaper, The Philanthropist, in Cincinnati, he and his paper immediately faced trouble. Most local newspapers and others tried to make him feel unwelcome. The Louisville Journal wrote a harsh article that almost directly threatened his newspaper.

On July 14, 1836, a mob attacked and destroyed Birney's printing press. On July 30, the press was attacked again. The printing press was broken into pieces, and the largest part was dragged through the streets and thrown into the river. The mob tried to harm Birney, but they couldn't find him. They then went on to destroy houses belonging to Black people. These events are known as the Cincinnati riots of 1836.

Despite these challenges, writing for his newspaper helped Birney develop ideas for fighting slavery through laws. He used these ideas while working with Salmon P. Chase to protect slaves who escaped to Ohio. In 1837, he was fined $50 for helping a slave. That same year, the American Anti-Slavery Society hired him as an officer, and he moved his family to New York.

The Liberty Party

In 1840, the American Anti-Slavery Society split, and Birney resigned because he did not support equal rights for women. In the same year, the Liberty Party, a new political party focused only on ending slavery, nominated Birney for president. He knew he wouldn't win, so he went as a representative to the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. The convention made him a vice-president, and his writings were shared across the United Kingdom.

When he returned, the Liberty Party used his legal skills to defend Black people and runaway slaves. They chose him as their candidate again in the 1844 presidential election. Their campaign aimed to take votes away from the Whig Party candidate, Henry Clay. In New York, Birney received 15,812 votes. Clay lost to the Democrat James K. Polk by only 5,106 votes. If Clay had won New York, he would have won the election.

Life in Michigan

In 1841, Birney moved to Saginaw, Michigan, with his new wife and family. He lived there for a few months until his home in Bay City, Michigan, was ready. Birney was involved in land development in Bay City. He helped plan the town, and Birney Park is named after him. He and other developers supported churches in the community and set aside money for their construction. Besides running for president, Birney also received 3023 votes for Governor of Michigan in 1845. He stayed in Michigan until 1855, when his health problems made him move to the East Coast.

While in Bay City, Birney worked on his farm and did agricultural activities, in addition to his legal work, land development, and national anti-slavery efforts. He even worked on his own fence because there wasn't much help available in the city.

His son, James Birney, came to Bay City (then called Lower Saginaw) to manage his father's business interests. James stayed in Bay City and continued his father's tradition of public service. He is buried in Pine Ridge Cemetery in Bay City.

Later Years and Death

In August 1845, Birney suffered from paralysis after a horseback riding accident. This condition came and went for the rest of his life. His speech became affected, and eventually, he could only communicate through gestures and writing, which was hard due to severe shaking. Because of his health, he ended his public career and his direct involvement in the abolitionist movement. However, he kept up with new developments. He died in New Jersey in 1857 at the Raritan Bay Union, a community settlement. He was surrounded by his abolitionist friends Theodore Dwight Weld, his wife Angelina Grimké Weld, and her sister Sarah Grimké. He believed that a war would be necessary to end slavery. He was buried at the Williamsburg Cemetery in Groveland, New York, where his second wife's family lived.

Honors

In 1889, a school for Black children in Washington, D.C., was named the Birney School in his honor. It later became an elementary school and was renamed Nichols Avenue Elementary School in 1962.

Family Life

James Birney married Agatha McDowell in 1816. Agatha's father was William McDowell, a U.S. district judge, and her mother was Margaret Madison, a distant relative of James Madison. James and Agatha had eleven children, but only six lived to adulthood: James, William, Dion, David Bell, George, and Florence. Agatha died in October 1838.

On March 25, 1841, Birney married Elizabeth Potts Fitzhugh. She was the sister of Henry Fitzhugh and Ann Carroll Fitzhugh (who was married to Gerrit Smith). James and Elizabeth had two children: Ann Hughes Birney (1844–1846) and Fitzhugh Birney (1842–1864).

Birney's oldest son, James, became the 13th Lieutenant Governor of Michigan and later the U.S. Minister to the Netherlands.

Four of Birney's sons fought in the American Civil War. David was a major-general in the Union Army and died from illness in October 1864. William was a U.S. inspector-general for United States Colored Troops and later became a U.S. attorney. Dion was a U.S. lieutenant who died during the Peninsula campaign in 1862. Fitzhugh was a U.S. major who died from pneumonia in June 1864.

Archived Materials

Birney's historical papers and documents are kept at the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, MI.

See also

In Spanish: James G. Birney para niños

In Spanish: James G. Birney para niños

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |