Cincinnati riots of 1836 facts for kids

The Cincinnati Riots of 1836 were a series of violent events in Cincinnati, Ohio, United States. These riots happened because of strong disagreements between white and black residents, especially as African Americans, some of whom had escaped slavery, were looking for jobs and competing with white workers.

These riots were part of a bigger pattern of violence happening at that time. Cincinnati had already seen a major riot in 1829, and another one against black residents would happen in 1841. After the Cincinnati riots of 1829, many African Americans lost their homes and belongings. This led some white people, like the "Lane rebels" from Lane Seminary, to become more supportive of black people's struggles. These "rebels" even left their school in 1834 because they believed in ending slavery. However, the rioters in 1836 were against ending slavery. They worried about losing their jobs if more black people competed for them, so they attacked both black residents and their white supporters.

Contents

Why the Riots Happened

Laws Against Black Freedom

In southern Ohio, black people faced many challenges to their freedom. This was due to laws called the Black Codes, passed in 1804 and 1807. These laws made it very hard for black people to live freely. For example:

- A black person's word was not accepted in court.

- They could not defend themselves against charges.

- They could not sue a white person.

- If they owned property, they had to pay taxes for schools, but their children were not allowed to attend those schools.

- Any black person moving to Ohio had to get two white men to sign a $500 bond, which was a lot of money back then.

- The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was strictly enforced. This law made it easy to capture runaway slaves. People who helped runaway slaves faced big fines.

Growing Tensions and New Ideas

Despite these harsh laws, more and more black people moved into Ohio during the early 1800s. This made tensions even worse. Some people who were against slavery but worried about the social changes it might bring suggested "colonization schemes." This meant sending free black people to places like Liberia or Haiti. The American Colonization Society even supported Ohio's Black Codes to encourage black people to leave. But others were brave enough to fight for the rights of free black people, even if it meant public disapproval.

The Anti-Slavery Newspaper

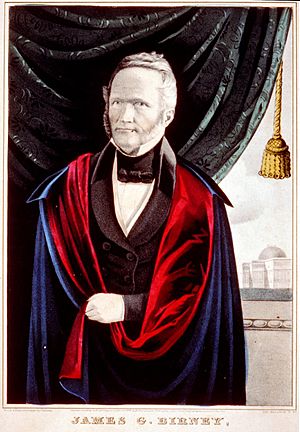

James G. Birney was a key figure in the fight against slavery. He used to own slaves in Alabama but then became a strong supporter of ending slavery. In January 1836, he started a newspaper called The Philanthropist. This newspaper was supported by the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society.

At first, the newspaper was printed in a nearby town, New Richmond. It was then sent across the Ohio River into Kentucky. The paper was full of articles against slavery. This made many Cincinnati businessmen angry. They worried that supporting anti-slavery ideas would hurt their business with the Southern states, which relied on slavery.

In late January 1836, over 500 important citizens held a meeting to oppose the anti-slavery movement. Birney attended, but he was not allowed to share his views.

The April Riot

In April, James Birney moved his newspaper press to Cincinnati. On April 11, 1836, a group of angry people attacked a black community. They hurt people, burned buildings, and forced many residents to leave their homes. Some Irish rioters burned down a building in the lower West End near the Ohio River. Several black people died during this violence. The riot was so bad that the governor had to step in and declare martial law, which meant the military took control to restore order.

The July Riots

Independence Day Celebration

On July 5, another riot started. This happened when African Americans held an Independence Day celebration. Black communities had celebrated this day for a long time. However, some white people saw it as a sign that black people wanted full equality and integration, which they opposed. James Birney, a well-known anti-slavery activist, attended the event, which further angered some people.

Birney's Press Destroyed Again

On July 12, 1836, about forty men broke into the building where Birney's newspaper press was located. These men were described as "respectable and wealthy gentlemen." They completely destroyed the press. They tore up newspapers, broke the printing machine into pieces, and dragged the damaged parts through the streets. Birney lost about $1,500 worth of equipment. He agreed to continue printing the paper only after the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society promised to cover up to $2,000 in damages.

After the press was destroyed, signs appeared around the city. One sign warned: "The Citizens of Cincinnati... are resolved to arrest their course. The destruction of their Press on the night of the 12th instant, may be taken as a warning." On July 17, another sign was posted:

"FUGITIVE FROM JUSTICE, $100 REWARD.

"The above sum will be paid for the delivery of one James G. Birney, a fugitive from justice, now abiding in the city of Cincinnati. Said Birney in all his associations and feelings is black; although his external appearance is white. The above reward will be paid and no questions asked by

OLD KENTUCKY".

More Attacks and Resistance

On July 23, the city mayor led a public meeting where people agreed to use all legal ways to stop anti-slavery publications. On July 30, a mob attacked Birney's press again and destroyed it, scattering the printing type. The rioters then threatened to burn down Birney's house, but his son convinced them not to. Men from Kentucky played a big part in this mob.

The angry white mob then marched to a black neighborhood known as the Swamp. There, they burned down several houses. They continued to Church Alley, where armed black residents tried to fight back, but their property was still destroyed.

Harriet Beecher Stowe, who lived in Cincinnati at the time and later wrote the famous novel Uncle Tom's Cabin, described what happened. She said that when the press was destroyed, the mayor watched without stopping it. He even told the rioters, "Well, lads, you have done well, so far; go home now before you disgrace yourselves." But the rioters continued their attacks, pulling down houses belonging to peaceful black residents. Other places like the "Gazette" office, the "Journal" office, Lane Seminary, and the water-works were also threatened.

By Tuesday morning, the city was very worried. A group of volunteers was formed. For three nights, they patrolled the streets with guns and legal permission from the mayor to stop the mob, even if it meant violence. It took several days for things to calm down. The authorities did not arrest anyone for the riots.

What Happened Next

The Ohio Anti-Slavery Society wrote about the riots and thought about why they happened. They noted that when black people were preparing for their July 5 procession, a white citizen started to verbally abuse them. A black man responded, and this might have started the chain of events. Another possible reason was that many visitors from the hot Southern states were in Cincinnati. The desire to please these visitors might have led to the attacks on the anti-slavery newspaper.

An 1888 book about Harriet Beecher Stowe mentioned that during the riots, "free negroes were hunted like wild beasts through the streets of Cincinnati." It also said that only the distance and muddy roads saved Lane Seminary and the anti-slavery supporters at Walnut Hills from being attacked. These events likely shaped Stowe's strong feelings about civil rights.

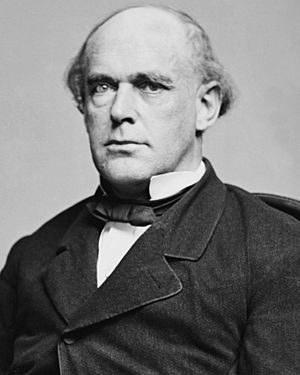

Salmon P. Chase, who later became a very important judge, was against the anti-slavery movement until these riots. He was shocked when his sister had to flee the mob and hide in his house. He found the riot "disgusting and horrible." He then organized a large meeting to support law and order. Later, he helped with a lawsuit that resulted in $1,500 in compensation for the owners, printer, and editor of The Philanthropist. Chase then became a very important leader in the movement to end slavery.

The Philanthropist newspaper started printing again and continued for many years.

Discussing the riots, a writer named Harriet Martineau criticized the businessmen of Cincinnati. She said they were "more guilty in this tremendous question of Human Wrongs than even the slave-holders of the south" because they violated the freedom of speech. William Ellery Channing agreed, telling James Birney that anti-slavery activists were not just fighting for black people, but also for the freedom of thought, speech, and the press.

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |