Kentucky in the American Civil War facts for kids

Kentucky was a very important border state during the American Civil War. At first, Kentucky tried to stay neutral, meaning it didn't pick a side. But when Confederate General Leonidas Polk tried to take control of the state, Kentucky's leaders asked the Union Army for help. Even though Confederate forces held much of Kentucky early on, the state mostly came under Union control after 1862. Historians study Kentucky's role by looking at how its people were divided, the battles and raids that happened, and how slavery ended there.

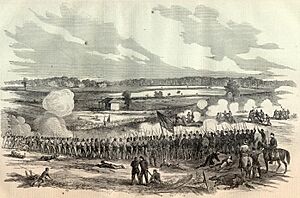

Many important battles took place in Kentucky, like Mill Springs and Perryville. Famous military leaders fought here, including Ulysses S. Grant for the Union and Nathan Bedford Forrest, a Confederate cavalry leader. Forrest caused a lot of trouble for the Union Army in western Kentucky, even attacking Paducah. Another Kentuckian, John Hunt Morgan, also led many cavalry raids across the state, challenging Union control.

Kentucky was the birthplace of Abraham Lincoln, who became the U.S. President, and his wife, Mary Todd. It was also the birthplace of Jefferson Davis, who became the President of the Confederacy. President Lincoln once said that losing Kentucky would be like losing the entire war. He believed Kentucky was essential for the Union to win.

About 25,000 to 40,000 Kentuckians fought for the Confederacy. Many more, between 74,000 and 125,000, joined the Union Army. This included about 24,000 to 25,000 Black Kentuckians, some of whom were free and others who had been enslaved.

Contents

Kentucky and the American Civil War

Before the War: Divisions in Kentucky

Before the war, people in Kentucky had different ideas about the issues causing the conflict. In 1860, nearly 20% of Kentucky's population were enslaved people. Many Kentuckians who supported the Union still believed slavery was acceptable. Kentucky also had strong ties to the Southern states because of the Mississippi River. This river was important for trade. Many families in Kentucky had come from Southern states like Virginia and Tennessee. However, some younger Kentuckians were starting to move north.

Kentucky had some of the best schools in the South, similar to North Carolina. Transylvania University was once a very famous college. By 1860, its fame was lessening, but other schools like Centre College and Georgetown College were becoming more well-known.

Kentucky was home to many important leaders. These included former Vice Presidents John C. Breckinridge and Richard M. Johnson. Famous figures like Henry Clay, John J. Crittenden, and John M. Harlan were also from Kentucky. Both U.S. President Abraham Lincoln and Confederate President Jefferson Davis were born here. However, by the time of the Civil War, Kentucky's politics were complicated. Many politicians were unsure which party to support. In the 1860 election, Kentucky voted for the Constitutional Union Party. This party tried to find a middle ground between the North and South.

Kentucky's Importance and Neutrality

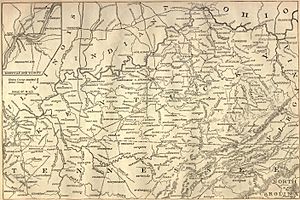

Kentucky was very important to both the North and the South. By 1860, it was the ninth largest state in population. It produced a lot of crops like tobacco, corn, wheat, and hemp. For the South, Kentucky was important because the Ohio River could act as a natural defense line along its northern border.

Kentucky Governor Beriah Magoffin felt that Southern states' rights were being ignored. He believed states had the right to leave the Union, but he wanted to avoid it. In December 1860, he suggested a plan to other Southern governors. This plan included enforcing the Fugitive Slave Act and ensuring the South had a say in laws about slavery. He hoped for a meeting of all states to find a peaceful solution, but events moved too quickly for this to happen.

Governor Magoffin called a special meeting of the Kentucky General Assembly in December 1860. He wanted Kentuckians to vote on whether to leave the Union. However, most lawmakers supported the Union and worried that a vote might lead to secession. Instead, they sent delegates to a Peace Conference in Washington, D.C.. They also asked Congress to consider solutions like the Crittenden Compromise, proposed by Kentuckian John J. Crittenden.

In March 1861, the General Assembly met again. They suggested a meeting of all border states in Frankfort, Kentucky's capital. This idea also didn't happen. Lawmakers also tried to pass a new amendment to the Constitution. This amendment would have protected slavery in states where it already existed.

President Lincoln understood how vital Kentucky was. In a letter from September 1861, he wrote: "I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game. Kentucky gone, we cannot hold Missouri, nor Maryland. These all against us, and the job on our hands is too large for us. We would as well consent to separation at once, including the surrender of this capitol." This shows how much he believed Kentucky was key to the Union's success.

War Begins: Neutrality Challenged

On April 15, 1861, President Lincoln asked Kentucky to send soldiers to help stop the rebellion. Governor Beriah Magoffin, who supported the South, refused. He said he would not send any men or money to fight against other Southern states. Most Kentuckians preferred to stay neutral, following John J. Crittenden's idea. They wanted Kentucky to be a peacemaker between the North and South. So, on May 20, 1861, Governor Magoffin officially declared Kentucky's neutrality.

Both sides respected Kentucky's neutrality at first. However, they strategically placed their forces nearby. Union camps were set up in Ohio and Indiana, just across the Ohio River. Confederate troops built Forts Donelson and Henry in Tennessee, close to Kentucky's southern border. Many Kentuckians left the state to join either the Union or Confederate armies. About 60 Union infantry regiments were formed from Kentucky, compared to 9 Confederate ones. However, many Kentuckians joined Confederate cavalry units. The famous "Orphan Brigade" of the Confederate Army was made up of Kentucky soldiers.

Realizing that neutrality was becoming harder to maintain, six important Kentuckians met. They included Governor Magoffin and John C. Breckinridge for the Confederates, and John J. Crittenden for the Union. They agreed to try and keep neutrality and created a board to manage the state's defense. However, Kentucky's own military forces were divided. The State Guard mostly favored the Confederacy, while the new Home Guard supported the Union.

Elections and Shifting Support

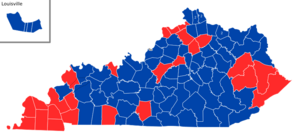

Public opinion in Kentucky began to change. In a special election on June 20, 1861, Unionist candidates won nine out of ten congressional seats. Confederate supporters only won in the Jackson Purchase area, which had strong economic ties to Tennessee. Many Confederate sympathizers did not vote, leading to a much lower turnout. Governor Magoffin faced another setback in the August 5 election for state lawmakers. Union supporters won a large majority in both the House and the Senate.

From then on, the General Assembly often overturned Governor Magoffin's decisions that favored the South. After a year of disagreements, Magoffin decided to resign. His chosen successor, James F. Robinson, became governor.

Soon after the 1861 election, Union General William "Bull" Nelson opened Camp Dick Robinson in Garrard County to recruit Union soldiers. When Crittenden complained about this breaking Kentucky's neutrality, Nelson said it was fine for loyal Kentuckians to gather under the Union flag on their own land. Governor Magoffin asked President Lincoln to close the camp, but Lincoln refused. Meanwhile, Confederate volunteers secretly gathered at Camp Boone in Tennessee, just south of Guthrie. Kentucky's neutrality was about to end.

Neutrality is Broken

On September 4, 1861, Confederate Major General Leonidas Polk broke Kentucky's neutrality. He ordered Brigadier General Gideon Johnson Pillow to occupy Columbus. Columbus was important because it was a railroad hub and located along the Mississippi River. Polk built Fort DeRussy there, equipping it with many cannons. He called it "The Gibraltar of the West." To control river traffic, Polk tried to stretch a huge anchor chain across the Mississippi River.

In response, Union Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant moved his forces from Cairo, Illinois, into Paducah, Kentucky, on September 6. This gave the Union control of a key railroad and the mouth of the Tennessee River. Governor Magoffin criticized both sides for violating neutrality. However, on September 7, the General Assembly voted to demand only Confederate forces withdraw. Magoffin vetoed this, but the Assembly overruled him. They then raised the U.S. flag over the state capitol in Frankfort, showing their loyalty to the Union.

With neutrality broken, both sides quickly moved to gain control. Confederate forces under Albert Sidney Johnston created a defensive line across southern Kentucky and northern Tennessee. This line stretched from Columbus in the west to Cumberland Gap in the east. Johnston sent Simon B. Buckner to fortify the center of this line in Bowling Green. Buckner built strong defenses there, preparing for a Union attack.

Confederate Government in Kentucky

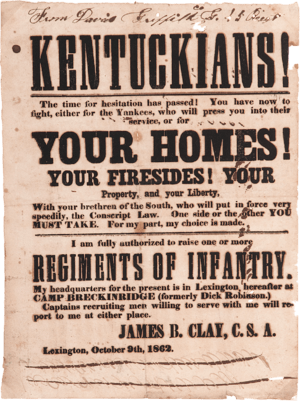

Since Kentucky's elected government supported the Union, a group of Southern sympathizers decided to create their own Confederate government for the state. After an initial meeting on October 29, 1861, delegates from 68 Kentucky counties met in Russellville on November 18. They voted to secede from the Union, adopted a new state seal, and elected George W. Johnson as governor.

Bowling Green, which was occupied by General Johnston, was named the capital. The delegates decided that Kentucky's existing laws would remain in effect, as long as they didn't conflict with the new Confederate government. Even though President Davis had some doubts about how this government was formed, Kentucky was admitted to the Confederacy on December 10, 1861. Kentucky was represented by the central star on the Confederate battle flag.

This provisional Confederate government existed throughout the war. It controlled more than half of Kentucky's territory early on. However, after 1862, it had very little real power. When General Johnston left Bowling Green in early 1862, the government's leaders traveled with his army. Governor Johnson was even killed in battle at Shiloh. The government briefly returned to Kentucky during Braxton Bragg's campaign but was forced out permanently after the Battle of Perryville. From then on, it mostly existed only on paper and dissolved after the war.

Major Battles and Union Control

Many small fights happened in Kentucky in 1861, including "Forrest's First Fight" at Sacramento. But the really big battles started in 1862.

Battle of Mill Springs

In January 1862, Union General George H. Thomas began to advance toward Confederate General George B. Crittenden's position at Mill Springs. Thomas's army moved slowly due to rain. Crittenden decided to attack them before they could get more soldiers from nearby Somerset. The battle began on January 19, 1862.

At first, Crittenden's forces were winning. But in the rain and fog, Confederate commander Felix Zollicoffer accidentally rode into the Union lines. A Confederate officer tried to warn him, but Zollicoffer was killed. This greatly discouraged the Confederates and changed the battle. Thomas's reinforcements arrived, forcing Crittenden's troops to retreat across the flooded Cumberland River. Many soldiers lost their lives, and Crittenden was blamed for the defeat.

Forts Henry and Donelson

General Johnston learned about the defeat at Mill Springs from a newspaper. However, he had bigger worries. Ulysses S. Grant was moving his Union forces down the Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers toward Forts Henry and Donelson. After Grant's victory at the Battle of Belmont, General Polk had moved most of his troops to Columbus, thinking Grant would attack there.

Lloyd Tilghman was left to defend Fort Henry with fewer than 3,000 men. Union troops attacked the fort on February 5, 1862, and Tilghman surrendered the next day.

General Johnston then ordered Pillow, Buckner, and John B. Floyd to defend Fort Donelson. No one was given overall command, which proved to be a mistake. Grant arrived at Donelson on February 13, outnumbered by about 3,000 Confederate soldiers. Floyd failed to use this advantage, and Grant received reinforcements the next day. On February 15, the Confederates almost created an escape route to Nashville, but arguments among their generals delayed the retreat. Floyd and Pillow fled, leaving Buckner in command. Buckner asked Grant for a cease-fire to discuss surrender. Grant's famous reply was that only "an unconditional and immediate surrender" would be accepted. This made Grant a Union hero and earned him the nickname "Unconditional Surrender" Grant.

Confederate Retreat

The fall of Forts Henry and Donelson made Polk's position at Columbus impossible to hold. The Confederates had to abandon "The Gibraltar of the West." With his defensive line broken, Johnston left Bowling Green on February 11, 1862. He retreated first to Nashville, then further south to join other Confederate generals in Corinth, Mississippi. Cumberland Gap, the last part of Johnston's line, finally fell to Union forces in June 1862.

Morgan's Daring Raids

First Raids in 1862

Soon after the Confederates left Kentucky, Confederate General John Hunt Morgan began his first raids into the state. In May 1862, Morgan's riders captured two Union trains at Cave City. His goal seemed to be to bother Union forces. He released everyone on board, returned one train, and sent the people back to Louisville. This raid encouraged Morgan to plan a bigger one in July.

On July 4, 1862, Morgan and his men left Knoxville, Tennessee, and captured Tompkinsville five days later. After a brief stop in Glasgow, they continued to Lebanon, capturing it on July 12. From there, they went to Harrodsburg and Georgetown. Seeing that Lexington was too well-defended, they attacked Cynthiana. Morgan won at Cynthiana, but with Union reinforcements closing in, he released all captured soldiers and rode to Paris.

As they left Kentucky, Morgan's cavalry gained 50 new recruits at Richmond. They also stopped in Somerset, where Morgan's telegraph operator, George "Lightning" Ellsworth, sent teasing messages to Union generals and newspaper publishers. After his escape, Morgan claimed to have captured and released 1,200 enemy soldiers, recruited 300 men, and taken hundreds of horses. He also used or destroyed supplies in seventeen towns, all with fewer than 100 casualties.

Smith and Bragg Advance into Kentucky

Morgan's successful raids encouraged Confederate General Edmund Kirby Smith to invade Kentucky. After talking with General Braxton Bragg in Chattanooga, Smith moved to push George W. Morgan out of Cumberland Gap in August 1862. The plan was for Smith to capture Cumberland Gap, then join Bragg in Middle Tennessee. Together, they would attack Don Carlos Buell in Nashville, then invade Kentucky.

However, the battle at Cumberland Gap dragged on, and Morgan refused to retreat. Smith decided to invade Kentucky instead of a long siege. He left a small force at the Gap and headed toward Lexington, abandoning the plan to meet Bragg in Nashville. This forced Bragg's hand, and he also entered Kentucky on August 28. As Smith moved toward Lexington, Indiana Governor Oliver P. Morton felt that Kentucky Governor Robinson wasn't doing enough to support the Union. Morton sent regiments into Louisville and even considered himself governor of both Indiana and Kentucky.

Battle of Richmond

When General "Bull" Nelson learned of Smith's advance, he prepared to fight at the Kentucky River. He wanted to use the better terrain and wait for more reinforcements. He ordered brigades under Mahlon Manson and Charles Cruft not to attack, but to fall back to Lexington. However, these orders were either not delivered in time or ignored.

After some small fights, Smith's army met Manson's brigade at Richmond, Kentucky, on August 30. Smith's more experienced troops broke the center of the Union line, and Manson retreated to Richmond Cemetery. By afternoon, General Nelson arrived and tried to rally his soldiers. He rode along the front, saying, "Boys, if they can't hit me, they can't hit a barn door!" Unfortunately, Nelson was soon hit twice by Confederate gunfire. Although seriously wounded, he escaped as Confederate cavalry tried to cut off the Union retreat. The Union lost 206 killed, 844 wounded, and 4,303 missing. Smith's army had only 98 killed, 492 wounded, and 10 missing. This was one of the most complete Confederate victories of the war.

Battle of Munfordville

While Smith continued toward Lexington, Bragg was just entering Kentucky, having been delayed until August 28. Bragg had been told there were plenty of supplies near Glasgow. But when Buell learned Bragg was in Kentucky, he left George Thomas to guard Nashville and moved his army to the well-fortified Bowling Green.

Meanwhile, Smith had sent Colonel John Scott to find Bragg. On the night of September 13, Scott met Union Colonel John T. Wilder at Munfordville and demanded his surrender. Scott requested help from James Chalmers' brigade, which arrived to support him. The attack began the next morning. Even though Scott's forces were outnumbered, they caused over 200 casualties in the early fighting. Chalmers then tried to scare Wilder into surrendering, sending a message that he had many more troops. Wilder replied, "Thank you for your compliments. If you wish to avoid further bloodshed, keep out of the reach of my guns."

Wilder soon received reinforcements of 4,000 men. Scott and Chalmers asked Bragg's main army for help. Bragg was angry but arrived the next day to take command. Bragg surrounded the town with forces under William J. Hardee and Leonidas Polk, delaying his attack until September 17. Bragg sent another request for surrender. At a meeting, Wilder made an unusual request to Bragg's subordinate, Simon B. Buckner: he asked to inspect the Confederate forces surrounding him to decide if surrendering was the right choice. Buckner, pleased by the compliment, agreed. After seeing the Confederate lines, Wilder surrendered.

Wilder's 4,000 men were released and sent to Bowling Green. Bragg hoped this would strain Buell's supplies. The delay caused by the Confederate victory at Munfordville might have cost them a much more important prize: Louisville.

Confederate Governor in Frankfort

While Bragg rested his troops, Buell marched north from Bowling Green and reached Louisville on September 25. Seeing his main goal taken by the Union, Bragg turned to Bardstown, expecting to meet Smith there. Smith was actually operating independently near Frankfort. Bragg realized that the lack of cooperation with Smith could lead to their defeat in Kentucky. He began to spread his troops into defensive positions at Bardstown, Shelbyville, and Danville.

Both Bragg and Smith were disappointed by the low number of Kentucky volunteers. Many rifles had been sent to the state for new recruits, but few Kentuckians joined, even though many sympathized with the Confederacy. Bragg hoped to encourage recruits by holding an inauguration ceremony for Richard Hawes, the governor of Kentucky's Confederate shadow government, in Frankfort. The elected Union government had fled to Louisville before the Confederates arrived.

The ceremony took place on October 4, 1862. First, Bragg spoke to the crowd, promising to defend Kentucky. Then Hawes, who had already taken his oath of office months earlier, gave a long speech. He promised that the provisional government would protect people and property until a permanent government could be established.

Bragg and Hawes's promises were short-lived. Before the inaugural ball could begin, Buell's forces arrived, firing artillery shells that broke up the celebration and sent the Confederates fleeing. Bragg had greatly underestimated how quickly Buell could advance. While preparations were being made for Hawes's inauguration, Buell was already pushing the Confederate army from Shelbyville. Bragg ordered Leonidas Polk to attack Buell's flank, but Polk was already under attack and retreating. Bragg began to retreat from Frankfort to Harrodsburg to regroup with Polk. Meanwhile, Smith prepared to defend Lexington, where he thought most of Buell's forces would go.

Battle of Perryville

By October 7, Polk's forces had fallen back to Perryville. The dry summer of 1862 meant water was scarce. When Union troops found water in Perryville's Doctor's Creek, they began to move toward the Confederate position. Bragg, like Smith, thought the main Union attack would be on Lexington and Frankfort. He ordered Polk's forces to attack the approaching Union troops and then meet Smith. However, the Confederate soldiers in Perryville realized a much larger force was coming and took up defensive positions. In fact, Buell, Charles Champion Gilbert, Alexander McCook, and Thomas Crittenden were all approaching Perryville.

The Confederates were not the only ones to misjudge the situation. When Bragg learned his men hadn't attacked as ordered, he came to Perryville himself to lead the attack. As the Confederates moved into attack positions, they stirred up so much dust that the Union forces thought they were retreating. This gave Bragg's men the advantage of surprise when they opened fire on McCook's forces at 2 PM on October 8. While McCook was pushed back on the left, the Union center held strong until the right flank began to collapse.

It wasn't until late afternoon that Buell learned of McCook's trouble. He sent two brigades to reinforce him, which stopped the Confederate advance north of Perryville. Meanwhile, small Confederate brigades encountered Gilbert's force of 20,000 men to the west and Crittenden's force, also 20,000 strong, to the south. Only then did Bragg realize he was facing Buell's main army and was greatly outnumbered. As night fell and stopped the battle, Bragg met with his officers and decided to retreat to Harrodsburg to meet Smith. From Harrodsburg, the Confederates left Kentucky through Cumberland Gap. For the rest of the war, the Confederacy made no major attempts to hold Kentucky.

On December 17, 1862, under General Order No. 11, thirty Jewish families, who had lived in the area for a long time, were forced from their homes. Cesar Kaskel, a well-known local Jewish businessman, sent a telegram to President Lincoln. He met with Lincoln and successfully got the order canceled.

Morgan's Christmas Raid

Because General Buell failed to stop Bragg and Smith's retreat from Kentucky, he was replaced by General William Rosecrans. Rosecrans camped in Nashville during the fall and early winter of 1862. Believing Rosecrans would soon begin a new campaign, Bragg sent John Hunt Morgan back into Kentucky in December 1862. Morgan's mission was to cut the Union supply line, the Louisville and Nashville Railroad. This raid was part of a larger plan to disrupt Union supplies.

Morgan's men entered Kentucky on December 22 and captured a Union supply wagon. On Christmas Day, Morgan's men rode through Glasgow toward Bacon Creek Station to destroy a railroad bridge. After overcoming strong Union resistance, Morgan's men destroyed the bridge and several miles of railroad track. They had successfully disrupted Rosecrans's supply line.

From Bacon Creek, Morgan rode to Elizabethtown, arriving on December 27. The Union commander, Colonel H. S. Smith, demanded Morgan's surrender. But Morgan surrounded Smith and, after a short fight, accepted Smith's surrender. Again, Morgan destroyed railroad infrastructure in the area, then planned his escape back to Tennessee.

Colonel John M. Harlan's artillery shelled Morgan's forces as they crossed the Rolling Fork River on December 29. First Brigade commander Basil W. Duke was seriously wounded. Duke was taken to Bardstown for medical care and recovered in time to rejoin the Confederate retreat the next day.

Freezing rain troubled Morgan's men as they camped at Springfield on the night of December 30. Worse, scouts reported a large Union force nine miles away at Lebanon. With Frank Wolford's men approaching, Morgan made the difficult decision to move out just after midnight in worsening weather. He ordered a few companies to create a distraction, pretending to attack Lebanon and burning fence rails to look like campfires. The main force continued to Campbellsville. The plan worked. After a march that many described as their most miserable night of the war, Morgan's men safely reached Campbellsville on New Year's Eve and captured some much-needed supplies. The next day, they went through Columbia and returned to Tennessee on January 3.

Morgan Crosses the Ohio River

After the Christmas Raid, there were only minor Confederate raids into Kentucky. Union commanders were frustrated by these unpredictable attacks. Morgan soon made his next raid very visible.

Many people believed Morgan had lost his daring spirit after his marriage in December 1862. Eager to prove them wrong and tired of guarding Bragg's flank, Morgan suggested a raid through Kentucky and across the Ohio River. Bragg, fearing an attack from Rosecrans, liked the idea of a distraction. Morgan gathered his men and on June 10, he told them that Bragg had approved a raid to Louisville, and possibly into Indiana and Ohio. He only told his trusted friend Basil Duke that Bragg's true orders were to stop at the Ohio River.

The raid was delayed by orders to intercept a Union raiding party. After three difficult weeks in muddy conditions, Morgan's men still hadn't found the enemy. They finally entered Kentucky on July 2, 1863. Two days later, Morgan fought Colonel Orlando Moore's forces at Tebbs Bend, where a bridge crossed the Green River near Campbellsville. As usual, Morgan demanded surrender. But Moore, noting it was Independence Day, replied, "It is a bad day for surrender, and I would rather not." Moore's forces won, and Morgan, having suffered 71 casualties, decided to bypass the bridge.

Morgan again met resistance at Lebanon. Despite a Confederate victory, his nineteen-year-old brother Tom was killed. From Lebanon, Morgan's men quickly moved through Springfield toward Bardstown. They learned that Union soldiers were less than a day behind them, and Louisville was preparing for another attack. Morgan had the element of surprise, however, choosing Brandenburg as his target. He sent an advance group to prepare for crossing the Ohio. On July 7, they captured two steamboats, the John B. McCombs and the Alice Dean. By midnight, all of Morgan's men were in Indiana.

Over the next few weeks, Morgan rode along the Ohio River, raiding Indiana and Ohio. On July 19, Union forces captured Duke and 700 of Morgan's men. Morgan escaped with 1,100 others. Union pursuit was intense, and Morgan lost exhausted men daily. His command dwindled to 363 men by the time he surrendered on July 26, 1863.

Morgan was taken to a prison in Columbus, Ohio, but escaped with several officers in November 1863. Despite the threat of a court martial from Bragg for disobeying orders, the Confederacy desperately needed leaders, so Morgan was given back his command.

Forrest's Raid on Paducah

After Morgan's capture in the summer of 1863, there were no major battles in Kentucky until the spring of 1864. Some Confederate infantry regiments wanted to become mounted infantry, but the Confederacy lacked horses. So, Nathan Bedford Forrest, who was operating in Mississippi, planned a raid on western Tennessee and Kentucky. Besides getting horses, Forrest wanted to disrupt Union supply lines, get supplies for Confederate forces, and discourage Black Kentuckians from joining the Union army.

On March 25, 1864, Forrest began his attack. He met Colonel Stephen G. Hicks at Fort Anderson and demanded an unconditional surrender. Hicks knew Forrest's main goals were supplies and horses, so he refused. Hicks was mostly right that Forrest wouldn't assault the fort. However, Confederate Colonel Albert P. Thompson, a local, briefly tried to capture it before being killed with 24 of his men. Forrest held the city for ten hours, destroying Union headquarters and supply buildings. He also captured 200 horses and mules before retreating to Mayfield. After the raid, Forrest gave his Kentuckian soldiers leave to get better clothing and horses. As agreed, every man returned to Trenton, Tennessee, on April 4.

Union newspapers bragged that Union forces had hidden the best horses and that Forrest had only captured horses stolen from private citizens. Furious, Forrest ordered Buford back into Kentucky. Buford's men arrived on April 14, pushed Hicks back into the fort, and captured another 140 horses from a foundry, exactly where the newspapers said they were hidden. They then rejoined Forrest in Tennessee. The raid was successful not only in getting horses but also in creating a distraction for Forrest's attack on Fort Pillow, Tennessee.

Black Soldiers Join the Union Army

After the U.S. Congress passed the Confiscation Acts and President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, enslaved people from Confederate states could join the Union Army. Although Kentucky slaves were not immediately freed by the Proclamation, many left their enslavers and fled. These formerly enslaved people came to Louisville and Camp Nelson and joined the U.S. Colored Infantry. Approximately 24,000 Black Kentuckians, both free and enslaved, served as Union soldiers.

Military Rule and End of the War

In response to the growing problem of guerrilla campaigns throughout 1863 and 1864, Major General Stephen G. Burbridge was given command over Kentucky in June 1864. This began a period of military control that lasted until early 1865, starting with martial law authorized by Lincoln. To bring peace to Kentucky, Burbridge strictly suppressed disloyalty and used economic pressure. His policy against guerrillas caused the most controversy. After disagreements with Governor Thomas E. Bramlette, Burbridge was removed from command in February 1865. Confederates remembered him as the "Butcher of Kentucky."

It is important to note that because of the Emancipation Proclamation, the strictness of Martial Law under Burbridge, and the enlistment of Kentucky's enslaved people into Union regiments, Union support among native Kentuckians greatly decreased by the end of the war. Kentucky had the second-largest number of African American Union enlistments, only behind Louisiana. This change in sentiment was observed by journalist Whitelaw Reid in 1865. He noted that there was more loyalty in Nashville than in Louisville, and that for the first time on his trip, he saw enslaved people serving dinner in Louisville. This feeling was also clear in the daily violence between Louisville citizens and Union soldiers leaving the city after the war, in what was known as the "war after the war" throughout the state.

See Also

In Spanish: Kentucky en la guerra de Secesión para niños

In Spanish: Kentucky en la guerra de Secesión para niños

- Civil War Museum (Bardstown)

- Confederate States of America – animated map of state secession and confederacy

- History of Kentucky

- History of slavery in Kentucky

- List of American Civil War monuments in Kentucky

- List of Kentucky Union Civil War units

- List of Kentucky Confederate Civil War units

- List of Kentucky's American Civil War generals

- Timeline of Kentucky in the American Civil War

- Southern Unionist

- List of Southern Unionists

- Kentucky's adjacent states in the American Civil War

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |