Louisville in the American Civil War facts for kids

During the American Civil War, Louisville was a very important place for the Union Army. It helped the Union keep Kentucky on their side. Louisville was a main center for planning, getting supplies, finding new soldiers, and moving troops for many battles, especially in the western part of the war. Even though battles like Perryville and Corydon happened nearby, Louisville itself was never attacked during the war.

Contents

Louisville Before the War (1850–1860)

In the 1850s, Louisville grew into a busy and rich city. But with this growth came problems, especially about race and different groups of people. Many immigrants from Europe, like Irish and Germans, moved to the city. Louisville also had a big slave market where enslaved African Americans were sold to the Deep South. Both people who owned slaves and those who wanted to end slavery lived in the city.

By 1850, Louisville was the tenth-largest city in the United States. Its population grew from 10,000 in 1830 to 43,000 in 1850. It became a major market for tobacco and a center for packing pork. The river route between Louisville and New Orleans was the busiest for moving goods and people in the entire western river system.

New Transportation and Industries

Louisville also benefited from new railroads. In 1855, the first train arrived, connecting Louisville to the rest of the country. The Louisville and Nashville Railroad (L&N) became very important for trade. It helped Louisville send furniture and other goods to Southern cities. Louisville was becoming an industrial city. Factories made things like girders, rails, and steamboats.

Louisville was also a big meat packing city, becoming the second largest in the nation for packing pork. It led the country in making hemp products and cotton bags. Farmington Plantation, owned by John Speed, was one of the biggest hemp farms in Louisville. Hemp was Kentucky's main farm product from 1840 to 1860.

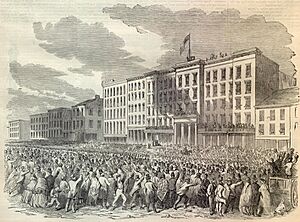

Growing Tensions and "Bloody Monday"

Many European immigrants, mostly Catholic, came to Louisville for jobs. They were different from the mostly Protestants already living there. Some local residents felt worried by these changes. They started to show anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic feelings.

A new political group called the Know-Nothing party grew popular. They were against immigrants and Catholics. By 1854, this party controlled the government in Jefferson County.

These tensions exploded on August 6, 1855, in an event called "Bloody Monday." During the mayor's election, Protestant mobs stopped immigrants from voting. They then started riots in Irish and German neighborhoods.

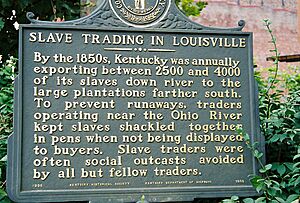

Slavery was also a huge issue. Louisville's economy made money from its busy slave market. Slave traders and businesses that fed, clothed, and moved slaves to the Deep South all added to the city's wealth. Even though fewer slaves were used for labor in central Kentucky by 1850, between 2,500 and 4,000 slaves were sold each year from Kentucky to the Deep South. Slave pens were located on Second Street.

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 made the slavery debate even worse. Louisville also had a population of free black people. Some of them managed to buy property. For example, Washington Spradling, freed in 1814, became a barber and owned property worth $30,000 by the 1850s. Louisville was a city that blended the farming culture of the South with the industrial culture of the North.

The Eve of War (1860)

In the 1860 United States presidential election, most Kentuckians did not vote for Abraham Lincoln. They did not like him because he wanted to end slavery. But they also did not vote for John C. Breckinridge, who was seen as supporting states leaving the Union. In 1860, Kentucky had 225,000 slaves, and 7.5 percent of Louisville's population were slaves. People in Kentucky wanted to keep slavery but also stay in the Union.

Most Kentuckians, including those in Louisville, voted for John Bell of Tennessee. His party wanted to keep the Union together and keep slavery as it was. Others voted for Stephen Douglas. Louisville gave 3,823 votes to John Bell and 2,633 votes to Stephen Douglas.

On December 20, 1860, South Carolina left the Union, and ten other Southern states followed. However, Kentucky chose to remain neutral at first, and later joined the Union.

War Breaks Out (1861)

The Civil War began on April 12, 1861, when Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina. The fort's commander was Union Major Robert Anderson, who was from Louisville.

After the attack, President of the United States Abraham Lincoln asked for volunteers. Kentucky's Governor, Beriah Magoffin, refused to send men to fight against the Southern states. Both Union and Confederate supporters in Kentucky agreed with him. On April 17, 1861, Louisville hoped to stay neutral. The city spent $50,000 for defense and named Lovell Rousseau as a general. Rousseau formed the Louisville Home Guard. Lincoln secretly sent weapons to the Home Guard.

Louisville residents were divided. Many wholesale merchants on Main Street, who traded a lot with the South, often supported the Confederacy. However, workers, small shop owners, and professionals like lawyers supported the Union. Some Confederate volunteers left Louisville by steamboat for New Orleans, and others left by train for Nashville. Union recruiters also gathered troops in Louisville, who then went to Indiana to join other Union groups.

On May 20, 1861, Kentucky officially declared its neutrality. Kentucky was important because of its location, the Ohio River, its natural resources, its people, and the L&N Railroad. Both President Lincoln and Confederate President Jefferson Davis tried not to push Kentucky to pick a side. Goods like uniforms, lead, and coffee were sent south from Louisville's L&N depot and steamboat wharfs. Even though Lincoln wanted to respect Kentucky's neutrality, a judge in Louisville ruled on July 10, 1861, that the U.S. government could stop shipments going south on the L&N railroad.

On July 15, 1861, the War Department allowed William "Bull" Nelson to set up a training camp. This camp, and others like it, effectively ended Kentucky's neutrality. General Rousseau set up a Union training camp across the river in Jeffersonville, Indiana. Governor Magoffin protested to Lincoln about these camps, but Lincoln ignored him.

In August 1861, Union supporters won most of the seats in the Kentucky State Assembly. Louisville residents remained divided. The Louisville Courier supported the Confederacy, while the Louisville Journal supported the Union.

On September 4, 1861, Confederate General Leonidas Polk invaded Columbus, Kentucky. In response, Union General Ulysses S. Grant entered Paducah, Kentucky. Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston then sent General Simon Bolivar Buckner to invade Bowling Green, Kentucky. Union forces saw this as a possible attack on Louisville. Johnston set up a defensive line from Columbus to the Cumberland Gap.

On September 7, the Kentucky State legislature, angry about the Confederate invasion, declared its loyalty to the Union. They also passed a law saying that anyone who joined the Confederate Army was no longer a citizen of Kentucky.

With Confederate troops in Bowling Green, Union General Robert Anderson moved his headquarters to Louisville. Louisville's mayor, John M. Delph, sent 2,000 men to build defenses around the city.

On October 8, General William Tecumseh Sherman took command of the Home Guard. Lovell Rousseau sent the Louisville Legion and other troops to protect the city. Sherman felt he needed many more men to fight the Confederates. Buckner's men destroyed a bridge near Lebanon Junction but did not attack Louisville.

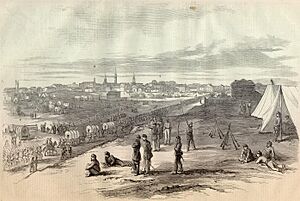

Louisville became a gathering place for Union troops heading south. Soldiers from Ohio, Indiana, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin arrived. Training camps were set up in different parts of the city.

Louisville Under Threat (1862–63)

By early 1862, Louisville had 80,000 Union troops. Many businesses, like gambling places and photography studios, opened to serve the soldiers.

In January 1862, Union General George Thomas defeated Confederate General Felix Zollicoffer at the Battle of Mill Springs. In February, Union General Ulysses Grant captured Fort Henry and Fort Donelson. Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston's defenses in Kentucky quickly fell apart. He had to retreat to Nashville and then to Corinth, Mississippi.

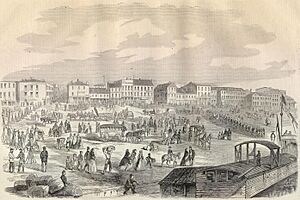

Even though the threat of invasion lessened, Louisville remained a key place for Union supplies and troops. Steamboats arrived and left the wharf with goods. Local businesses provided the Union army with cattle and hogs every day. Trains carried supplies south on the L&N railroad.

Confederate Invasion of Kentucky

In July 1862, Confederate generals Braxton Bragg and Edmund Kirby Smith planned to invade Kentucky. On August 13, Smith marched with 9,000 men towards western Kentucky. On August 30, Smith's Confederate forces defeated Union General William "Bull" Nelson's troops at the Battle of Richmond, Kentucky. This left Kentucky with no Union support. Nelson escaped back to Louisville. Smith marched into Lexington and sent cavalry to take Frankfort, Kentucky's capital.

Union General Don Carlos Buell's army moved back to Kentucky from Alabama. Confederate General John Hunt Morgan destroyed a railroad tunnel in Gallatin, Tennessee, cutting off supplies to Buell's army. Bragg decided to take Louisville. A main goal of the Confederate campaign was to capture the Louisville and Portland Canal to cut off Union supply routes on the Ohio River.

On September 16, Bragg's army reached Munfordville, Kentucky, and the Union forces there surrendered. Buell left Bowling Green and headed for Louisville. Fearing Bragg would capture the city, Union General William "Bull" Nelson ordered defenses built around Louisville. He also ordered pontoon bridges built across the Ohio River to help evacuate the city or bring in more troops from Indiana.

The Union Army arrived in time to stop the Confederates from taking the city. On September 25, Buell's tired and hungry men reached Louisville. Bragg moved his army to Bardstown but did not attack Louisville. Bragg wanted General Smith to join him, but Smith refused.

With Bragg's army nearby, the people of Louisville panicked. On September 22, 1862, General Nelson ordered an evacuation: "The women and children of this city will prepare to leave the city without delay." Hundreds of residents gathered at the wharf for boats to New Albany or Jeffersonville. With Frankfort in Confederate hands, Governor Magoffin and the state legislature met in the Jefferson County Courthouse in Louisville. Troops and volunteers worked day and night to build defenses around the city. New Union regiments arrived.

Instead of taking Louisville, Bragg went to Frankfort to install Confederate Governor Richard Hawes. On September 26, Confederate cavalry captured Union soldiers near Eighteenth and Oak in Louisville. Southern forces came within two miles of the city but were not strong enough to invade.

The Death of General Nelson

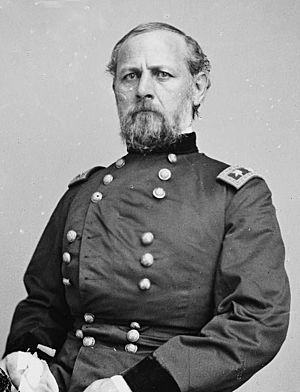

The War Department ordered "Bull" Nelson to command the new Army of the Ohio. General Jefferson C. Davis (not the Confederate President) met with General Nelson in Louisville. Nelson gave Davis command of the city militia. An argument broke out between them, and Nelson slapped Davis. Davis left, borrowed a pistol, and returned to shoot and kill Nelson. Nelson died fifteen minutes later.

With Nelson dead, General Don Carlos Buell took command. On October 1, the Union army marched out of Louisville with 60,000 men. Buell sent a small force to Frankfort to trick Bragg. The trick worked, and Bragg left Frankfort, thinking the main Union force was headed there. Bragg decided to gather all Confederate forces at Harrodsburg, Kentucky.

On October 8, 1862, Buell and Bragg fought at Perryville, Kentucky. Bragg's 16,000 men attacked Buell's 60,000 men. The Union suffered 845 dead, 2,851 wounded, and 515 missing. The Confederates lost 3,396 men. Even though Bragg won the battle, he decided to leave Kentucky and head for Tennessee.

Hospitals and Prisons

After the battle, thousands of wounded soldiers came to Louisville. Hospitals were set up in schools, homes, factories, and churches. The United States Marine Hospital of Louisville became a hospital for wounded Union soldiers. By early 1863, the War Department and the U.S. Sanitary Commission had set up nineteen hospitals. By June 1863, 930 deaths had been recorded in Louisville hospitals. Cave Hill Cemetery set aside plots for the Union dead.

Louisville also had to deal with Confederate prisoners. The Union Army Prison, or "Louisville Military Prison," was located on Green Street and 5th Street, then moved to 10th and Broadway Streets. By August 1862, Confederate prisoners of war were taken there. In December 1863, the prison held over 2,000 men, including political prisoners, Union deserters, and Confederate prisoners.

The prison was made of wood and covered a whole city block. It had a high fence and barracks. The prison hospital was attached to the prison. Union authorities also took over a large house on Broadway to use as a military prison for women.

Emancipation Proclamation and Black Soldiers

On September 22, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. It stated that as of January 1, 1863, all slaves in the states that had rebelled would be free. This did not immediately free slaves in Kentucky, but slave owners felt threatened. Some Kentucky Union soldiers even left the army because they disagreed with freeing slaves.

Many slaves came to the Union camp, so the Army set up a camp for them. A minister named Thomas James helped at the camp, setting up a church and school. Both adults and children started learning to read. James also helped protect slaves from being held illegally.

The Union's decision to recruit slaves into the army (which gave them freedom) turned some slave owners in Kentucky against the U.S. government. Later, the fighting by guerrillas and harsh actions by Union General Stephen G. Burbridge as military governor of Kentucky made more citizens angry.

The Taylor Barracks in Louisville recruited black soldiers for the United States Colored Troops. Slaves gained freedom by serving the Union. Slave women married to these soldiers also gained freedom. Black Union soldiers who died were buried in Louisville's Eastern Cemetery.

In the summer of 1863, Confederate John Hunt Morgan led his famous raid into Ohio and Indiana. He traveled through north-central Kentucky, capturing Union soldiers. Before crossing the Ohio River into Indiana, Morgan and his men captured two steamboats.

After New Orleans and Vicksburg, Mississippi, were captured in July 1863, the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers were open for Union boats.

Military Rule (1864)

Guerrilla warfare caused a lot of problems in Kentucky. On January 12, 1864, Union General Stephen G. Burbridge became the Military Commander of Kentucky.

On February 4, 1864, important Union generals, including Ulysses S. Grant and William S. Rosecrans, met at the Galt House in Louisville. They discussed major war plans. Later, Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman met there again to plan the Spring campaign.

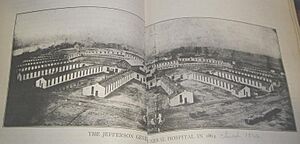

On February 21, 1864, Jefferson General Hospital, one of the largest hospitals during the Civil War, was built across the Ohio River in Port Fulton, Indiana. It cared for injured soldiers.

On July 5, 1864, President Abraham Lincoln temporarily stopped the right to a trial (called habeas corpus). This meant people could be jailed without a trial. Lincoln also declared martial law in Kentucky, giving military authorities full power. Civilians accused of crimes would be tried in military courts, not regular courts. On the same day, General Burbridge was given absolute power as military governor of Kentucky.

On July 16, 1864, Burbridge issued Order No. 59. It stated that if an unarmed Union citizen was killed, four guerrillas from prison would be publicly shot. On August 7, Burbridge issued Order No. 240, making Kentucky a military district under his direct command. Burbridge could take property from people he thought were disloyal and execute suspects without trial.

During July and August, Burbridge started building more forts in Kentucky. He got permission to build forts in Mount Sterling, Lexington, Frankfort, and Louisville. Louisville's fort was planned to be larger than the others. Soldiers built these forts, except in Frankfort and Louisville, where local workers were used.

Eleven forts protected Louisville in a ring about ten miles long. The first fort built was Fort McPherson. It was meant to be a strong point if an attack came before other forts were finished. General Hugh Ewing, the Union commander in Louisville, ordered city officials to provide workers for the forts. He even ordered the arrest of "loafers" (people without jobs) to work on construction.

Each fort was a simple earth and timber structure with a ditch and a movable drawbridge. They had underground storage for artillery shells. The forts were placed to provide overlapping fire. The guns in Louisville's forts were never fired in battle, only for salutes.

Burbridge used his orders to stop guerrilla activity in Kentucky and Louisville.

By the end of 1864, Burbridge ordered the arrest of twenty-one important Louisville citizens, including a chief judge, for treason. He had captured guerrillas brought to Louisville and executed. General Ewing, the Union commander in Louisville, was often sick and not involved in these actions.

In the 1864 United States presidential election, Burbridge tried to interfere with the election. Despite this, Kentucky citizens voted strongly for Union General George B. McClellan over Lincoln. In December 1864, President Lincoln appointed James Speed as the U.S. Attorney General.

War Comes to a Close (1865–66)

Even as the Confederacy was falling apart in January 1865, Burbridge continued executing guerrillas. On January 20, 1865, Nathaniel Marks was executed by a firing squad in Louisville, even though he claimed he was innocent. On February 10, Burbridge's time as military governor ended. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton replaced him with Major General John Palmer.

On March 12, Union forces captured 20-year-old Captain M. Jerome Clarke, also known as "Sue Mundy." He was executed three days later in Louisville after a military trial where he was charged as a guerrilla. He was not allowed a lawyer or witnesses.

On April 9, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses Grant. On April 14, Confederate General Joseph Johnston surrendered to Union General William T. Sherman, ending the Civil War.

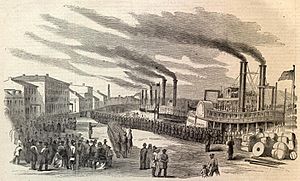

On May 15, Louisville became a center for soldiers from midwestern and western states to leave the army. On June 4, 1865, the headquarters for the Union Armies of the West was set up in Louisville. Many troops came to Louisville by steamboat. On July 4, 1865, Union General William T. Sherman visited Louisville for a final inspection. By mid-July, the armies were disbanded, and the soldiers went home.

Because of the Emancipation Proclamation, the harsh military rule under Burbridge, and the enlistment of Kentucky slaves into Union regiments, support for the Union among native Kentuckians greatly decreased by the end of the war.

On December 18, the Kentucky legislature allowed all who served in the Confederacy to get their full Kentucky citizenship back. They also removed the law that called Confederates traitors. The legislature allowed former Confederates to run for office. On February 28, 1866, Kentucky officially declared the war over.

After the War

After the war, Louisville continued to grow. Manufacturing increased, new factories opened, and goods were transported by train. New industrial jobs attracted both black workers, including freed slaves from the South, and foreign immigrants. Many former Confederate officers became lawyers, insurance agents, real estate agents, and politicians, taking control of the city. This led to the saying that Louisville joined the Confederacy after the war ended.

Women who supported the Confederacy formed groups. After the war, these women made sure Confederate dead were buried and raised money to build memorials. By the 1890s, groups like the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) promoted the "Lost Cause" idea, which was a way of remembering the war from the Southern side. In 1895, a Confederate monument was built near the University of Louisville campus.

The "Lost Cause" movement was strong in Louisville between 1865 and 1935. Many native Kentuckians regretted supporting the Union because the war changed the old social order in Kentucky. Henry Watterson, a Confederate veteran and editor of the Courier-Journal newspaper, was a key figure. He promoted the idea of a strong and independent South within the United States. He called Louisville "The Gateway to the South."

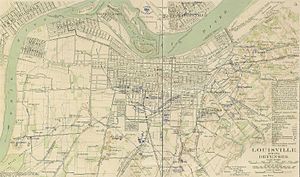

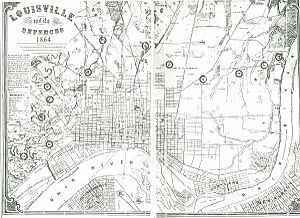

Civil War Defenses of Louisville (1864–65)

Around 1864–65, city defenses, including eleven forts ordered by Union General Stephen G. Burbridge, formed a ring about ten miles long. These forts stretched from Beargrass Creek to Paddy's Run. Today, nothing remains of these forts. They included, from east to west:

- Fort Elstner

- Fort Engle

- Fort Saunders at Cave Hill Cemetery

- Battery Camp Fort Hill (2)

- Fort Horton

- Fort McPherson on Preston Street

- Fort Philpot

- Fort St. Clair Morton

- Fort Karnasch

- Fort Clark (1865)

- Battery Gallup (1865)

- Fort Southworth on Paddy's Run at the Ohio River (now a sewage treatment plant).

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |