Louisville and Portland Canal facts for kids

The Louisville and Portland Canal was a 2-mile (3.2 km) long canal built to help boats get around the Falls of the Ohio River near Louisville, Kentucky. These falls were the only natural barrier for boats traveling between the start of the Ohio River in Pittsburgh and the port of New Orleans on the Gulf of Mexico. For a long time, merchants from places like Pennsylvania and Cincinnati wanted a way to bypass these falls.

The canal first opened in 1830. It was owned by a private company called the Louisville and Portland Canal Company. However, over time, the U.S. government slowly bought out the company. The government had already put a lot of money into building, taking care of, and improving the canal.

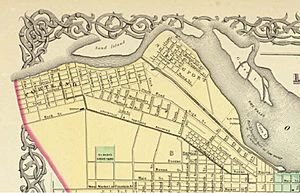

In 1962, the Louisville and Portland Canal was updated and renamed the McAlpine Locks and Dam. Even today, people still call the actual canal the "Louisville and Portland Canal" or "Portland Canal." It runs between the Kentucky riverbank and Shippingport Island, from about 10th Street to the locks at 27th Street. This canal was the first big improvement made on a major river in the United States.

Contents

History of the Canal

Why the Canal Was Needed

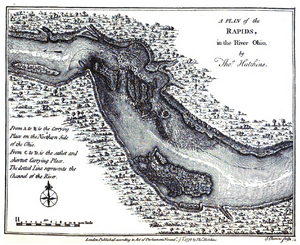

The Falls of the Ohio were the only natural obstacle for boats traveling from the Ohio River's source in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, all the way to the Gulf of Mexico. Because of these falls, early cities in Kentucky like Louisville, Portland, and Shippingport grew. This was because cargo had to be carried around the rapids, except for a few weeks each spring when the river water was very high.

While locals liked the income from carrying goods, merchants upriver, especially in Pittsburgh and Cincinnati, didn't like the extra cost and trouble. The situation caused prices to change a lot up and down the river, as there was always a huge amount of goods shipped during the short high-water season.

Early on, people wanted to build a canal. In 1781, the town of Louisville asked the Virginia General Assembly for permission to build one. Two years later, an engineer named Christopher Colles also asked the government for land to start a canal company, but they said no.

Serious plans for a canal started in the early 1800s. People from Cincinnati especially wanted a northern route through Indiana to reduce competition from Louisville. Both Kentucky and Indiana created canal companies in 1805, but nothing happened. In 1808, Albert Gallatin, who was in charge of the U.S. Treasury, suggested the national government help pay for a canal on the Kentucky side. The United States Senate approved this idea in 1810 and 1811, but the House disagreed.

In 1811, William Lytle II, who founded Cincinnati, planned out Portland and sold land to help pay for his own canal project. The Indiana Canal Company tried again in 1818, starting to dig with private and state money. But a dam failed, and a financial crisis in 1819 stopped their efforts. There were even rumors that the Indiana dam was sabotaged. A canal could hurt Louisville's economy, which relied on moving, storing, and shipping goods, as well as hotels and entertainment. However, some locals thought a canal would help local manufacturing.

A Private Company Builds the Canal

Even though the government built the National Road in the 1810s and New York built the Erie Canal in the 1820s (which cut shipping costs by about 95%), it was hard to get money for a public canal in Kentucky. This was because some politicians and people in Louisville were against it.

Instead, Charles Thurston of Louisville suggested creating a private company called the Louisville and Portland Canal Company. This company was allowed to charge a toll of 20 cents per ton of goods. It could operate the canal forever and had the right to take land needed for construction. In 1824, it was estimated that building the canal would take one year and cost $300,000.

The company officially started in 1825. Important members included James Guthrie, who became president. The company was allowed to sell up to 6,000 shares of stock at $100 each. They raised $350,000 from the first sale in March 1826, and another $150,000 soon after. Much of this money came from investors in Philadelphia. In May 1826, the United States Congress also decided to buy 1,000 shares.

Construction began in 1826. It soon became clear that the canal had to be dug through solid rock. The cost estimate went up to over $375,000, and it would take two years to build. Local investors learned about the problems first, and some stopped paying for their shares, which reduced the company's money. It's said that Abraham Lincoln worked on the canal's construction in 1827. The path of the canal needed changes, and Congress invested another $133,500 in 1829.

The company was still running out of money by the end of 1829. A third request for funds from Congress was stopped by the new President, Andrew Jackson. He believed the government should not give money to private companies. So, the company had to borrow $154,000 in 1830. By this time, the canal was worth over $1,000,000, and the federal government owned $290,000 of it.

The first ship, the SS Uncas, passed through the partly finished locks in December 1830. The canal was fully finished in 1833, six years later than planned. It was 50 feet (15 m) wide, which was very large compared to projects like the Erie Canal. This was meant to let full-sized ships pass through.

However, steamboats quickly became bigger and more powerful. This meant the canal was almost too small soon after it opened. At the same time, the demand for goods from the north increased. The canal raised its prices to 40 cents per ton in 1834 and 60 cents per ton in 1837. Even with higher prices, traffic grew from 170,000 tons in 1834 to 300,000 tons in 1839. Louisville's "carrying trade" also grew, and a railroad line was built next to the canal in 1838.

Customers were unhappy with the company's high tolls and its lack of interest in making the canal better. The lower end of the canal opened into a narrow part of the river with a strong current, which was dangerous. People from Ohio and Pennsylvania in Congress sometimes tried to get the government to buy the company completely. But these efforts were always stopped in the House by politicians from Kentucky and the South, who believed in states' rights. Even Indiana representatives still hoped to build their own canal as late as 1842.

The company decided to solve the problem itself. Instead of funding expansions or paying out profits to shareholders, they used the money to buy back privately owned shares at a higher price. This slowly increased the government's ownership. Even with financial crises in 1837 and 1843, and a toll reduction to 50 cents per ton in 1842, the company made a lot of money. The government finished buying out all the private shares in 1855.

The Government Takes Over

By the 1850s, about 40% of the steamboats on the Ohio River were too big for the canal. Their cargo had to be moved around the Falls. Even though the government owned the company after 1855, Congress found it hard to formally take control of the canal. Bills to do so from 1854 to 1860 failed because of questions about whether it was constitutional, economical, or efficient.

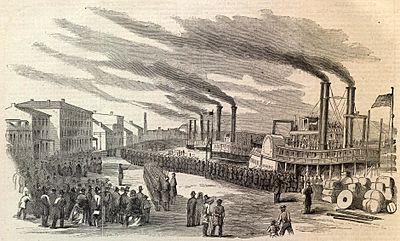

In the end, the government simply told the company to pay for the needed improvements itself. A plan costing $865,000 was approved and started in 1860. But it was quickly put on hold because of the Civil War. The canal was a target for Confederate forces in Kentucky. Some even wanted to destroy it. But Union forces controlled the state, so the threat didn't happen. However, the loans for the original plan meant the company owed $1.6 million by 1866.

After the Civil War, the Army Corps of Engineers was finally allowed to take over improvements for the canal in 1867. Two new locks, each 390 feet (119 m) long and 90 feet (27 m) wide, opened in February 1872.

Full Government Control

In May 1874, Congress passed a bill allowing the Corps of Engineers to take full control of the canal. They also allowed the Treasury to pay off the debts for the recent improvements. By 1877, even though railroads were being used much more, traffic on the canal had tripled. This traffic was mostly heavy, low-value industrial supplies like coal, salt, and iron ore. In 1880, because of pressure from producers upriver, Congress completely removed the canal's tolls. This meant the government paid all the canal's expenses from the Treasury, without making a profit.

A new lock was built in 1921 as part of Congress's plan to make the Ohio River easier to navigate. Further expansions in 1962, which increased the canal's width to 500 feet (152 m), led to the canal being known as the McAlpine Locks and Dam.

How the Canal Changed Things

In the 1800s, the canal's high tolls and limited size actually helped Louisville. It allowed shareholders to make good profits without greatly hurting the local economy that relied on moving and storing goods. The gradual buyout meant the original owners were well paid for their investments.

Louisville grew a lot, while its former partners, Portland and Shippingport, became less important. Portland initially kept growing and became its own town in 1834. It agreed to let the canal be widened and to become part of Louisville in 1837. In return, its wharf would be the end point for the Lexington and Ohio Railroad. But when the railroad only connected Portland with Louisville before going bankrupt in 1840, Portland left Louisville again from 1842 to 1852, before rejoining. Much of Portland was destroyed or torn down after the floods of 1937 and 1945. Shippingport, which became part of Louisville in 1828 and was made an island by the canal, slowly declined until the government bought out the remaining families in 1958.

At the same time, the canal's limitations meant it didn't help other communities up and down the river as much. Even at its highest tolls, the canal did lower freight rates along the river. However, it didn't lead to much lower prices for goods. In fact, prices fell faster in the 25 years before the canal opened than in the 25 years after. In the 1850s and 1860s, the canal's usage stayed about the same, even though river traffic was growing a lot.

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |