Indiana in the American Civil War facts for kids

Indiana, a state in the Midwest, played a very important part in helping the Union during the American Civil War. Even though some people in Indiana were against the war, and many in southern Indiana had family ties to the South, Indiana strongly supported the Union.

Indiana sent about 210,000 soldiers, sailors, and marines to fight for the Union. These soldiers fought in 308 battles. Most of these battles were in the western part of the war, between the Mississippi River and the Appalachian Mountains. Sadly, 25,028 Hoosiers (Indiana residents) died during the war. About 7,243 died in battle, and 17,785 died from diseases.

The state government helped by buying equipment, food, and supplies for the troops. Indiana was a rich farming state and had the fifth-largest population in the Union. Its location, large population, and farms were key to the North's success. Hoosiers provided soldiers, a good railroad network, access to the Ohio River and the Great Lakes, and farm products like grain and livestock. The state faced two small attacks by Confederate forces. One major attack in 1863 caused a brief panic in southern Indiana and its capital city, Indianapolis.

Indiana also had many political arguments during the war. This was especially true after Governor Oliver P. Morton stopped the state legislature from meeting. This legislature was controlled by Democrats, and some of them were against the war. Big debates happened about slavery, allowing African Americans to serve in the military, and the draft. These arguments sometimes led to violence. In 1863, the state legislature failed to pass a budget. This meant the state could not collect taxes. Governor Morton then got money from federal and private loans to keep the government running. He did this even though it was outside his normal powers.

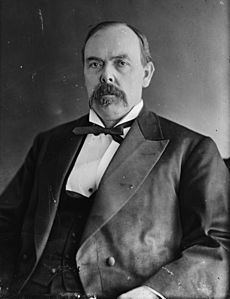

The Civil War changed Indiana's society, politics, and economy forever. More people started moving to central and northern Indiana. This led to a decrease in population in the southern part of the state. More factories and businesses grew in Indiana's cities and towns during the war. This started a new time of economic success. By the end of the war, Indiana was less rural than before. For many decades after the war, Indiana's votes were very close between the two main parties. This made it a "swing state" that often decided national elections. Between 1868 and 1916, five Indiana politicians were chosen as vice-presidential candidates. In 1888, Benjamin Harrison, a former Civil War general from Indiana, was elected president of the United States.

Contents

How Indiana Helped the Union

| War | American Civil War |

| Started | April 12, 1861 |

| Ended | April 9, 1865 |

| Soldiers | 208,367 Hoosiers |

| Sailors | 2,130 Hoosiers |

| Killed | 24,416 Hoosiers |

| Wounded | 48,568 Hoosiers |

| Result | Union victory |

Indiana was the first western state to get ready for the Civil War. When people in Indiana heard about the attack on Fort Sumter, South Carolina, on April 12, 1861, they were surprised but reacted quickly. The next day, two big meetings were held in Indianapolis. People decided that Indiana would stay with the Union. They also decided to send men right away to stop the rebellion. On April 15, Indiana's governor, Oliver P. Morton, asked for volunteers to meet the state's goal set by President Abraham Lincoln.

Indiana's location in the Midwest, its large population, and its farming production were very important for the Union to win. Indiana had the fifth-largest population among Union states. This meant it could provide many soldiers. Its railroad system and access to the Ohio River and the Great Lakes helped transport troops and supplies. Its farms provided grain and livestock, which became even more important after the South's rich farmland was lost.

Sending Soldiers to War

On April 15, 1861, President Lincoln asked for 75,000 volunteers for the Union army. On the same day, Governor Morton offered 10,000 Indiana volunteers. The state's first goal was to provide six regiments, which was 4,683 men, for three months of service. Orders were given on April 16 to form these regiments and gather in Indianapolis. On the first day, 500 men arrived. Within a week, more than 12,000 Hoosier volunteers had signed up. This was nearly three times more than needed for the first goal.

Governor Morton and Lew Wallace, Indiana's adjutant general, set up Camp Morton at the state fairgrounds in Indianapolis. This was the first place for volunteers to gather and train. (Camp Morton later became a prison camp for Confederate soldiers in 1862). By April 27, Indiana's first six regiments were fully ready. They were called the First Brigade, Indiana Volunteers, led by Brigadier General Thomas A. Morris. Men who were not chosen for these first regiments could volunteer for three years of service or go home. Some companies joined the state militia and were called into federal service later.

Indiana was second among all states in how many of its military-aged men served in the Union army. Indiana sent 208,367 men, about 15 percent of its total population, to the Union army. Another 2,130 served in the navy. Most of Indiana's soldiers were volunteers. About 11,718 re-enlisted. About 10,846 soldiers left without permission.

In the early months of the war, many Hoosiers volunteered. But as the war continued and more soldiers died, the state government had to use the draft to get enough men. The military draft, which started in October 1862, caused many disagreements in the state. It was especially unpopular among Democrats. They saw it as a threat to personal freedom. They also opposed rules that allowed a man to pay $300 to avoid serving or pay someone else to take his place. In October 1862, 3,003 Hoosier men were drafted. Later drafts brought the total to 17,903.

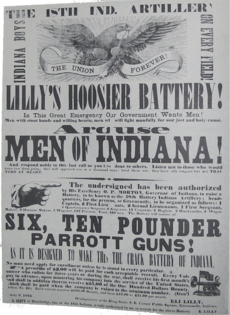

Indiana's volunteers and drafted men formed 129 infantry regiments, 13 cavalry regiments, 3 cavalry companies, 1 heavy artillery regiment, and 26 light artillery batteries for the Union army. Indiana also created its own volunteer militia called the Indiana Legion. Formed in May 1861, the Legion protected Indiana's citizens from attacks and kept order within the state.

More than 35 percent of Hoosiers who joined the Union army became casualties. About 24,416, or 12.6 percent of Indiana's soldiers, died in the war. An estimated 48,568 soldiers were wounded, which is double the number killed. Indiana's total war-related deaths reached 25,028. This included 7,243 from battle and 17,785 from disease.

Important Leaders from Indiana

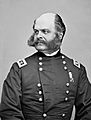

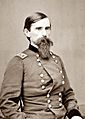

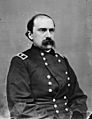

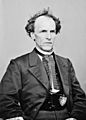

By the end of the war, 46 Union army generals had lived in Indiana at some point. These leaders included Don Carlos Buell, Ambrose Burnside, Lew Wallace, Robert H. Milroy, and Joseph J. Reynolds, among others.

-

Maj. Gen.

Don Carlos Buell -

Maj. Gen.

Ambrose Burnside -

Maj. Gen.

Lewis Wallace -

Maj. Gen.

Edward Canby -

Maj. Gen.

Robert H. Milroy -

Maj. Gen.

Joseph J. Reynolds -

Maj. Gen.

Alvin P. Hovey -

Bvt. Maj. Gen.

George H. Chapman -

Bvt. Maj. Gen.

Robert Sanford Foster -

Bvt. Maj. Gen.

Edward M. McCook -

Bvt. Maj. Gen.

James W. McMillan -

Bvt. Maj. Gen.

John M. Brannan -

Bvt. Maj. Gen.

Robert A. Cameron -

Bvt. Maj. Gen.

John F. Miller -

Bvt. Maj. Gen.

Jefferson C. Davis -

Bvt. Maj. Gen.

Nathan Kimball -

Bvt. Maj. Gen.

Solomon Meredith -

Brig. Gen.

Ebenezer Dumont -

Brig. Gen.

William M. Dunn -

Brig. Gen.

James H. Lane -

Brig. Gen.

Mahlon D. Manson -

Brig. Gen.

Charles Cruft -

Brig. Gen.

Robert F. Catterson -

Brig. Gen.

Walter Q. Gresham -

Brig. Gen.

William Grose -

Brig. Gen.

Milo S. Hascall -

Brig. Gen.

Pleasant A. Hackleman -

Brig. Gen.

George F. McGinnis -

Bvt. Brig. Gen.

John Coburn -

Bvt. Brig. Gen.

Thomas W. Bennett -

Bvt. Brig. Gen.

Benjamin Harrison -

Bvt. Brig. Gen.

Frederick Knefler -

Bvt. Brig. Gen.

George P. Buell -

Col.

Daniel McCauley -

Bvt. Col.

Henry W. Lawton -

1st. Lt.

Ambrose Bierce

Training and Support for Soldiers

More than 60 percent of Indiana's regiments gathered and trained in Indianapolis. Other training camps were set up in places like Fort Wayne, Gosport, Jeffersonville, and South Bend.

Governor Morton was known as the "Soldier's Friend." He worked hard to get equipment, training, and care for Union soldiers. Indiana's state government paid for a large part of preparing its regiments for war. This included housing, feeding, and equipping them before they joined the main Union armies. To get weapons, the governor sent agents to buy them for the state. For example, Robert Dale Owen bought over $891,000 worth of weapons, clothes, blankets, and cavalry gear. The state government bought another $260,000 in supplies. To make ammunition, Morton set up a state-owned arsenal in Indianapolis. This arsenal helped the Indiana militia and home guard. It also served as a backup supply place for the Union army. The state arsenal operated until April 1864, employing 700 people at its busiest time. Many of its workers were women. A federal arsenal was also built in Indianapolis in 1863.

The Indiana Sanitary Commission, started in 1862, and soldiers' aid groups across the state raised money and collected supplies for troops. Hoosiers also helped soldiers and their families in other ways. They set up a Soldiers' Home and a Ladies' Home, and an Orphans' Home. These places helped Indiana's soldiers and their families when they passed through Indianapolis.

During the war, some women took on the extra job of running family farms and businesses. Hoosier women also helped the war effort as nurses and volunteers in charity groups. The local Ladies' Aid Societies were common. In January 1863, Governor Morton and the Indiana Sanitary Commission started hiring women to work as nurses. They worked in military hospitals and on hospital ships and trains in Indiana and the South. Others served near battlefields. We don't know how many Indiana women became wartime nurses. But several died during their service, including Eliza George from Fort Wayne.

Wounded soldiers were cared for at Indiana hospitals. These were in places like Clark County (Port Fulton, near Jeffersonville), Jefferson County (Madison), and Marion County (Indianapolis). Jefferson General Hospital at Port Fulton, Indiana, was briefly the third-largest hospital in the United States. Between 1864 and 1866, this hospital treated 16,120 patients.

Prison Camps in Indiana

Indianapolis was home to Camp Morton. This was one of the Union's largest prisons for captured Confederate soldiers. Lafayette, Richmond, and Terre Haute, Indiana, also held prisoners of war sometimes.

Military Cemeteries

Two national military cemeteries were created in Indiana because of the war. In 1882, the government opened the New Albany National Cemetery in New Albany, Indiana. In 1866, a national cemetery was approved for Indianapolis. Crown Hill National Cemetery was set up inside Crown Hill Cemetery, a private cemetery northwest of downtown.

Conflicts and Raids

Indiana troops fought in 308 military battles. Most of these were between the Mississippi River and the Appalachian Mountains. Soldiers from Indiana were on most Civil War battlefields. They fought from the first battle involving Hoosier troops at the Battle of Philippi on June 3, 1861, to the Battle of Palmetto Ranch on May 13, 1865. Almost all the fighting happened outside Indiana. Only one important conflict, called Morgan's Raid, happened in Indiana during the war. This raid caused a brief panic in Indianapolis and southern Indiana. Two smaller attacks happened before it.

Confederate Raids into Indiana

On July 18, 1862, during the Newburgh Raid, Confederate officer Adam Johnson briefly captured Newburgh. This made it the first town in a Northern state to be captured during the Civil War. Johnson and his men succeeded by making the town's Union soldiers believe they had cannons on the hills. (They were just camouflaged stovepipes). This raid made the federal government realize Indiana needed a permanent force of Union Army soldiers to stop future attacks.

On June 17, 1863, Confederate Captain Thomas Hines and about 80 men crossed the Ohio River. They were looking for horses and support from Hoosiers in southern Indiana. This was in preparation for a planned attack by Confederate troops led by John Hunt Morgan. During this small attack, known as Hines' Raid, local citizens and Indiana's home guard chased the Confederates. They captured most of them without a fight. Hines and a few of his men escaped back into Kentucky.

Morgan's Raid, the main Confederate attack into Indiana, happened a month after Hines' raid. On July 8, 1863, General Morgan crossed the Ohio River at Mauckport, Indiana, with 2,400 soldiers. A small group from the Indiana Legion first tried to stop them. But they pulled back after Morgan's men started firing artillery from the river's southern side. The state militia quickly went back towards Corydon, Indiana. A larger group was gathering there to block Morgan's advance. The Confederates quickly moved on the town and fought in the Battle of Corydon. After a short but strong fight, Morgan took control of high ground south of town. Corydon's local militia and citizens quickly gave up after Morgan's artillery fired two warning shots. Corydon was looted, but its buildings were not badly damaged. Morgan continued his raid north and burned most of the town of Salem.

When it looked like Morgan was heading toward Indianapolis, panic spread through the capital city. Governor Morton had called up the state militia as soon as he knew Morgan planned to cross into the state. More than 60,000 men of all ages volunteered to protect Indiana. Morgan thought about attacking Camp Morton, the prisoner-of-war camp in Indianapolis. He wanted to free over 5,000 Confederate prisoners there. But he decided against it. Instead, his raiders suddenly turned east and moved towards Ohio. With Indiana's militia chasing them, Morgan's men continued to raid and steal their way towards the Indiana-Ohio border. They crossed into Ohio on July 13. By the time Morgan left Indiana, his raid had become a desperate attempt to escape to the South. He was captured on July 26 in Ohio.

Indiana's Regiments in Battle

Many of Indiana's regiments fought bravely in the war. The 19th Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment, 20th Indiana Infantry Regiment, and 27th Indiana Infantry Regiment had the most casualties among the state's infantry regiments, based on their total number of soldiers.

Indiana's first six regiments formed during the Civil War were the 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th, and 11th Indiana infantry regiments. These men volunteered for three months at the start of the war. But this short time was not enough. Most of these soldiers re-enlisted for three more years of service.

By the end of 1861, forty-seven Indiana regiments had joined the army. Most men signed up for three years. Most of these three-year regiments were sent to the western part of the war. In 1862, another forty-one regiments from Indiana joined. About half went to the eastern part of the war, and the other half stayed in the west. In 1863, six more regiments joined to replace soldiers lost in the first two years. On July 8, 1863, thirteen more temporary regiments were created during Morgan's Raid. These men volunteered for three months. The regiments broke up once Morgan's threat was gone. In 1864, twenty-one Indiana regiments joined. As the fighting slowed down, most of Indiana's regiments left the army by the end of 1864. But some continued to serve. In 1865, fourteen more Indiana regiments joined for a year of service. On November 10, 1865, the 13th Regiment Indiana Cavalry was the last state regiment to leave the U.S. Army.

The 11th Indiana Infantry Regiment, also known as the Indiana Zouaves, was led by Lew Wallace. It was the first regiment formed in Indiana during the Civil War and the first to fight in battle. The 11th Indiana fought in the Battle of Fort Donelson, the Siege of Vicksburg, and the second day of the Battle of Shiloh. In 1861, the 9th Indiana Infantry Regiment was one of the first Hoosier regiments to see action. The 9th Indiana fought in many major battles, including the Battle of Shiloh, the Battle of Stones River, the Atlanta Campaign, and the Battle of Nashville.

The 14th Indiana Infantry Regiment was called the "Gibraltar Brigade." This was because it held its position at the Battle of Antietam. It also secured Cemetery Hill on the first day of the three-day Battle of Gettysburg. There, it lost 123 men. The 19th Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment, part of the Iron Brigade, helped greatly in some of the war's most important battles. This included the Second Battle of Bull Run. But it was almost completely destroyed at the Battle of Gettysburg, where it had 210 casualties. The 19th Indiana suffered the heaviest battle losses of any Indiana unit. About 15.9 percent of its men were killed or died from wounds during the war. The 27th Indiana Infantry Regiment earned the nickname "giants in the cornfield" at the Battle of Antietam. This regiment also fought at the Battle of Chancellorsville, the Battle of Gettysburg, and in the Atlanta Campaign. The 27th Indiana's casualties were 15.3 percent of its total soldiers, almost as many as the 19th Indiana.

Most of Indiana's military units were formed within towns or counties. But some units were formed based on ethnic groups. These included the 32nd Indiana, a German-American infantry regiment, and the 35th Indiana, made up of Irish Americans. The 28th Regiment U.S. Colored Troops was the only black regiment formed in Indiana during the war. It was created in Indianapolis between December 1863 and March 1864. It trained at Indianapolis's Camp Fremont and had 518 enlisted men who signed up for three years. The regiment lost 212 men during the conflict. The 28th fought in the Siege of Petersburg and at the Battle of the Crater. Twenty-two of its men were killed there. At the end of the war, the regiment served in Texas. It left the army on November 8, 1865.

The last soldier to die in the Civil War was a Hoosier. Private John J. Williams was serving in the 34th Regiment Indiana Infantry. He died at the Battle of Palmetto Ranch on May 13, 1865.

Indiana's Politics During the War

Hoosiers voted for the Republicans in 1860. In January 1861, Indiana's new lieutenant governor, Oliver P. Morton, became governor. This happened after Henry Smith Lane left the office to become a U.S. Senator. Hoosiers also helped Abraham Lincoln win the presidency in 1860 and voted for him again in 1864. Lincoln won 51.09 percent of Indiana's popular vote in 1860, earning its 13 electoral votes. In 1864, Lincoln won Indiana again with 53.6 percent of the state's popular vote.

Governor Morton was one of Lincoln's "war governors." They worked closely together during the war. However, as more soldiers died, Hoosiers started to question the war. Many worried about the government gaining too much power and people losing their freedom. This led to big conflicts between the state's Republicans and Democrats.

Southern Influence in Indiana

The Civil War showed how much the South influenced Indiana. Many parts of southern and central Indiana had strong ties to the South. Many early settlers in Indiana came from Virginia and Kentucky, which were Confederate states. Governor Morton once told President Lincoln that "no other free state is so populated with southerners." Morton believed this made it harder for him to be as strong as he wanted to be.

Because they were across the Ohio River from Louisville, Kentucky, Indiana cities like Jeffersonville and New Albany saw more trade and military activity. This was partly because Kentucky wanted to stay neutral in the war. Also, Kentucky had many Confederate supporters. Military bases in southern Indiana were needed to support Union actions against Confederates in Kentucky. It was safer to store war supplies on the north side of the river. Jeffersonville became an important military supply center for Union troops going south. Towards the end of the war, Port Fulton was home to the third-largest hospital in the United States, Jefferson General Hospital.

In 1861, Kentucky's governor, Beriah Magoffin, did not allow pro-Union forces to gather in his state. He also gave a similar order for Confederate forces. Governor Morton often helped Kentucky's pro-Union government during the war. He became known as the "Governor of Indiana and Kentucky." He allowed Kentuckians to form Union regiments on Indiana soil. Kentucky troops, especially from Louisville, gathered at Indiana's Camp Joe Holt. Camp Joe Holt was set up in Clarksville, Indiana.

Jesse D. Bright represented Indiana in the United States Senate. He had been a leader among Indiana's Democrats before the war. In January 1862, Bright was removed from the Senate. This was because he was accused of being disloyal to the Union. He had written a letter for a weapons seller addressed to "His Excellency, Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederation." In the letter, Bright offered the seller's services as a firearms supplier. Bright's replacement in the Senate was Joseph A. Wright, a pro-Union Democrat and former Indiana governor. As of 2015, Bright was the last senator to be removed by the Senate.

Political Conflicts and Disagreements

Hoosiers worked together to support the war at the beginning. But political differences soon led to the "most violent political battles" in the state's history. The main debates, which also caused violence, were about slavery, allowing African Americans to serve in the military, and the draft.

On April 24, 1861, Governor Morton spoke to a special meeting of the Indiana General Assembly. He wanted the legislature to approve borrowing and spending money to buy weapons and supplies for Indiana's troops. Morton also urged Indiana's lawmakers to put aside party differences and unite to defend the Union. But Republicans and Democrats did not cooperate for long. At first, the Democratic-controlled legislature supported Morton's plans and passed the laws he asked for. However, after the state legislature ended its session in May, some important Democrats changed their minds about the war. In January 1862, the Democrats made their position clear at a state meeting. Indiana's Democrats said they supported the Union and the war effort. But they were against freeing slaves and ending slavery.

After the elections in the fall of 1862, Governor Morton worried that the Democratic majority in the legislature would try to stop the war effort. He feared they would reduce his power and vote to leave the Union. When the legislature met in 1863, all but four Republican lawmakers stayed away from Indianapolis. This stopped the general assembly from having enough members (a quorum) to pass laws. This included laws to fund the state government or collect taxes. This quickly led to a crisis. The state government started running out of money and was almost broke. Going beyond his constitutional powers, Morton asked for millions of dollars in federal and private loans to avoid this crisis. To get money, Morton turned to James Lanier, a rich banker from Madison. Lanier gave the state over $1 million in loans without needing security. Morton's plan worked. He was able to fund the state government and the war effort in Indiana. There was little the legislature could do but watch.

Indiana's political divisions got worse after the Emancipation Proclamation (1863). This made freeing slaves a goal of the war. Many Democrats who had supported the war now openly opposed it. Governor Morton started to crack down on people who disagreed. In May 1863, during a famous event, the governor had soldiers break up a Democratic state meeting in Indianapolis. This event was later called the Battle of Pogue's Run. The Indiana General Assembly did not meet for a regular session again until June 1865.

Most of the state strongly supported the Union. But a group of Southern supporters called the Knights of the Golden Circle had a strong presence in southern Indiana. This group was enough of a threat that General Lew Wallace, who led Union forces in the area, spent a lot of time stopping their activities. By June 1863, the group was successfully broken up. Many Golden Circle members were arrested without formal charges. Pro-Confederate newspapers were stopped from printing anti-war material. And the right to habeas corpus (the right to be brought before a court) was denied to anyone suspected of disloyalty. In response to Governor Morton's actions, Indiana's Democratic Party called him a "dictator." Republicans argued that the Democrats were using disloyal tactics during the war.

Confederate agent Thomas Hines went to French Lick in June 1863. He was looking for support for Confederate General John Hunt Morgan's planned raid into Indiana. Hines met with Sons of Liberty "major general" William A. Bowles. He asked if Bowles could help Morgan's upcoming raid. Bowles claimed he could gather 10,000 men. But before the plan was final, Hines was told that Union forces were coming and he fled the state. As a result, Bowles did not help Morgan's raiders. This caused Morgan to treat anyone in Indiana who claimed to support the Confederacy very harshly.

Large-scale support for the Confederacy among Golden Circle members and Southern Hoosiers generally decreased after Morgan's Confederate raiders looted many homes that displayed Golden Circle banners. This happened even though these homes claimed to support the Confederates. As Confederate Colonel Basil W. Duke remembered, "The Copperheads and Vallandighammers fought harder than the others" against Morgan's raiders. When Hoosiers did not support Morgan's men in large numbers, Governor Morton slowed his crackdown on Confederate sympathizers. He believed that since they failed to help Morgan, they would also fail to help a larger invasion.

Although raids into Indiana were rare, smuggling goods into Confederate territory was common. This was especially true early in the war. At that time, the Union army had not yet pushed the front lines far south of the Ohio River. New Albany and Jeffersonville, Indiana, were starting points for many Northern goods smuggled into the Confederacy. The Cincinnati Daily Gazette pressured both towns to stop trading with the South. This was especially true with Louisville, because Kentucky's neutrality was seen as helping the South. A fake steamboat company was set up to travel the Ohio River between Madison, Indiana, and Louisville. Its boat, the Masonic Gem, made regular trips to Confederate ports.

Southern Supporters in the Confederate Army

We don't know the exact number of Hoosiers who served in Confederate armies. It's believed they were not very many. Most likely, they traveled to Kentucky to join Confederate regiments formed there. Former U.S. Army officer Francis A. Shoup, who briefly led the Indianapolis Zouave militia unit, left for Florida before the war. He eventually became a Confederate brigadier general.

Republican Control in the Legislature

After the elections in 1864, the state's Republican legislative majority reached an important point. The North was slowly tightening its blockade of the South. The new Republican-controlled legislature fully supported Governor Morton's plans. They worked to meet the state's commitments to the war effort. In 1865, the Indiana General Assembly approved the loans Morton had gotten to run the state government. They took on these loans as state debt. They also praised Morton for his actions during that time.

After the War

News of Confederate General Robert E. Lee's surrender at Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia, reached Indianapolis at 11 p.m. on April 9, 1865. This caused immediate and joyful public celebrations. The Indianapolis Journal called them "demented." A week later, the community's excitement turned to sadness. News of Lincoln's assassination arrived on April 15. Lincoln's funeral train passed through Indianapolis on April 30. About 100,000 people visited his bier at the Indiana Statehouse.

Economic Changes After the War

The Civil War changed Indiana's economy forever. Despite difficulties during the war, Indiana's economy got better. Farmers received higher prices for their crops. Railroads and businesses grew in the state's cities and towns. A shortage of workers gave laborers more power to ask for better pay. The war also helped create a national banking system. By 1862, there were thirty-one national banks in the state. The war brought prosperity, especially to Indianapolis. Its population more than doubled during the war, reaching 45,000 by the end of 1864.

More factories and industrial growth in Indiana's cities and towns started a new time of economic success. By the end of the war, Indiana was less rural than before. Overall, the war caused Indiana's industries to grow very quickly. However, the state's southern counties grew slower than others after the war. The state's population shifted to central and northern Indiana. New industries and cities grew around the Great Lakes and the railroad stations built during the war. In 1876, Colonel Eli Lilly opened a new medicine laboratory in Indianapolis. This later became Eli Lilly and Company. Indianapolis was also the wartime home of Richard Gatling. He invented the Gatling Gun, one of the world's first machine guns. Although his invention was used in some Civil War battles, the U.S. Army did not fully adopt it until 1866. Charles Conn, another war veteran, founded C. G. Conn Ltd. in Elkhart, Indiana. Making musical instruments became a new industry for that town.

Development after the war was different in southern Indiana. The state's trade along the Ohio River decreased during the war. This was especially true after the Mississippi River was closed to trade with the South. There was also more competition from the state's growing railroad network. Some of Indiana's river towns, like Evansville, recovered by transporting Union troops across the Ohio River. But others did not. Before the war, New Albany was the largest city in the state. This was mainly because of its trade with the South. But its trade decreased during the war. After the war, many in Indiana saw New Albany as too friendly to the South. New Albany's strong steamboat-building industry ended in 1870. The last steamboat built there was named the Robert E. Lee. New Albany never became as important as it was before the war. Its population stayed around 40,000. Only the old Mansion Row district remains from its boom period.

Political Changes After the War

When the war ended, the state's Democrats were upset about how Republicans treated them during the war. But they quickly made a comeback. Indiana became the first state after the Civil War to elect a Democratic governor, Thomas Hendricks. His election started a time when Democrats controlled the state. This reversed many of the political gains Republicans made during the war.

Indiana's U.S. senators strongly supported the radical Reconstruction plans proposed by Congress. Senators Oliver Morton, who became a senator after being governor, and Schuyler Colfax voted to remove President Andrew Johnson from office. Morton was especially disappointed when Congress failed to remove him.

When the South became strongly Democratic again in the late 1870s, Indiana was closely split between the two parties. It became one of a few key swing states that often decided who would control Congress and the presidency. Five Hoosier politicians were chosen as vice-presidential candidates between 1868 and 1916. This showed how important the state's voters were to national political parties. In 1888, at the peak of the state's political influence after the war, former Civil War general Benjamin Harrison was elected president. He served from 1889 to 1893.

Social Changes After the War

More than half of Indiana's households, based on an average family size of four people, had a family member fight in the war. This meant the war's effects were felt widely across the state. More Hoosiers died in the Civil War than in any other conflict. Even though twice as many Hoosiers served in World War II, almost twice as many died in the Civil War. After the war, programs were started to help wounded soldiers with housing, food, and other basic needs. Also, orphanages and asylums were set up to help women and children.

After the war, some women who had been very active in supporting the war at home used their organizing skills for other causes. These included the movement to ban alcohol and the right for women to vote. For example, in 1874, Zerelda Wallace became a founder of the Indiana chapter of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union. She was the wife of former Indiana governor David Wallace and stepmother of General Lew Wallace. She served as its first president.

War Memorials

Many war memorials were built to honor Indiana's Civil War veterans. One of the largest in Indiana is the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument in downtown Indianapolis. After twenty years of discussion, construction for the monument began in 1888. It was finally finished in 1901.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |