Cemetery Hill facts for kids

Cemetery Hill is an important hill on the Gettysburg Battlefield. It saw fighting every day of the Battle of Gettysburg, from July 1 to 3, 1863. This hill was the northern end of the Union Army's defensive line, which looked like a "fish-hook." It was a good spot for cannons because it had gentle slopes and wasn't heavily wooded, unlike nearby Culp's Hill.

Contents

What Cemetery Hill Looks Like

Cemetery Hill sits south of downtown Gettysburg. It's about 503 feet (153 meters) above sea level, which is 80 feet (24 meters) higher than the town center. The top of the hill stretches for about 700 yards (640 meters) from southwest to northeast.

A small dip in the hill separates East Cemetery Hill from the rest. The Baltimore Pike road crosses here. The slopes to the north and west are gentle, but East Cemetery Hill has a steeper climb. Important roads like the Baltimore Pike, Emmitsburg Road, and Taneytown Road cross the hill.

History Before the Battle

In 1854, the Evergreen Cemetery was built on the south side of Cemetery Hill. Its gatehouse, built in 1855, was even used as a headquarters during the battle.

Before the main battle, on June 26, 1863, Confederate cavalry led by Elijah V. White briefly took over the hill. They captured some horses hidden by local people, then left. The telegraph station from Gettysburg was then moved to Cemetery Hill for safety. The hill remained quiet until the Union Army arrived.

Day One: The Battle Begins

On July 1, 1863, Union Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard left soldiers and cannons on Cemetery Hill. This was a backup plan in case the Union Army had to retreat from fighting north and west of Gettysburg. And they did! Cemetery Hill became the safe place for Union troops from the I Corps and XI Corps as they fell back.

A big question after the battle was why Confederate Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell didn't attack and capture Cemetery Hill that day. His subordinate, Brig. Gen. William "Extra Billy" Smith, thought Union troops were coming from the east. This made General Early delay his attack on the hill. It turned out there were no Union troops coming from the east. Smith was the only general not praised by Early after the battle.

Day Two: Fierce Fighting

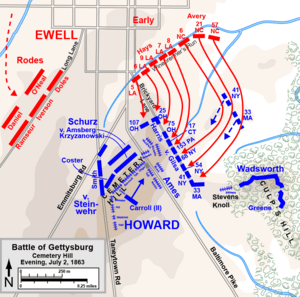

On July 2, Confederate General Robert E. Lee ordered attacks on both ends of the Union line. Lt. Gen. James Longstreet attacked the Union left flank. Meanwhile, Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell was supposed to make a smaller attack on the Union right. This was meant to distract Union soldiers and keep them from helping Longstreet. If Ewell saw a good chance, he could turn his small attack into a full-scale one.

Ewell started his attack at 4 p.m., after hearing Longstreet's cannons. For three hours, he only fired cannons from Benner's Hill, about a mile away. Union defenders on Cemetery Hill took some damage, but they fired back even harder. Cemetery Hill is 50 feet (15 meters) taller than Benner's Hill, giving the Union gunners a big advantage. Ewell's cannons had to pull back with heavy losses. His best young artillerist, 19-year-old Joseph W. Latimer, was badly wounded and later died.

Around 7 p.m., as the Confederate attacks on the Union left were slowing down, Ewell decided to launch his main infantry attack. He sent three brigades from Maj. Gen. Edward "Allegheny" Johnson's division up the eastern slope of Culp's Hill. They attacked Union soldiers behind stone walls. These Union soldiers, led by Brig. Gen. George S. Greene, held off the Confederates for hours. The fighting on Culp's Hill would continue the next day.

Soon after the Culp's Hill attack began, around 7:30 p.m., Ewell sent two brigades from Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early's division. They attacked East Cemetery Hill from the east. Early also told Maj. Gen. Robert E. Rodes's division to get ready to attack Cemetery Hill from the northwest.

The two brigades from Early's division were led by Brig. Gen. Harry T. Hays (his own Louisiana Tigers) and Col. Isaac E. Avery (Hoke's Brigade). They started their attack from a line near Winebrenner's Run. Hays had about 1,200 men, and Avery had 900. Another brigade was behind them but did not join the fight.

Defending East Cemetery Hill were two Union brigades from the XI Corps, now led by Brig. Gen. Adelbert Ames. These brigades had fought hard on July 1 and were much smaller now. Col. Andrew L. Harris's men were at a low stone wall on the northern end of the hill. Col. Leopold von Gilsa's brigade was spread out along Brickyard Lane (also called Winebrenner's Lane, now Wainwright Avenue) and on the hill.

Two regiments were even further out in Culp's Meadow, expecting an attack from Johnson's division. Further west on the hill were other Union divisions. Col. Charles S. Wainwright commanded the cannons on the hill. The steep slope of East Cemetery Hill made it hard for cannons to fire down on the attacking soldiers. But they did their best, firing "canister shot" (like a giant shotgun blast).

The Confederate attack started with a loud "Rebel yell" against the Ohio soldiers at the stone wall. Union General Ames had moved some soldiers, leaving a gap. Hays's Louisianans quickly jumped over the stone wall and through the gap. Other Confederates found weak spots. Soon, some attackers reached the cannons at the top of the hill. Others fought in the dark with the remaining Union soldiers behind the stone wall.

On the hill's crest, the Union cannon crews fought hand-to-hand with the Confederates. Major Samuel Tate of the 6th North Carolina wrote that his men and some Louisianans reached the cannons. He said, "It was now fully dark. The enemy stood with tenacity never before displayed by them, but with bayonet, clubbed musket, sword, pistol, and rocks from the wall, we cleared the heights and silenced the guns."

However, other historians say the Confederates were only briefly at the cannons. If Cemetery Hill, the "keystone" of the Union line, had fallen, the Union Army might have had to leave Gettysburg. But the next day, the cannons here helped stop the famous Pickett's Charge.

Generals Howard and Schurz heard the fighting and quickly sent soldiers from West Cemetery Hill to help. Howard's lines were getting thin, so he asked Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock for help. Hancock ordered one of his brigades, led by Col. Samuel S. Carroll, to rush from Cemetery Ridge. They charged through the dark from the cemetery just as the Confederate attack was fading. Carroll's men secured the cannons and pushed the North Carolinians back down the hill. Other Union soldiers pushed the Louisianans back down the hill.

Defending East Cemetery Hill would have been much harder if the Confederate attack had been better coordinated. To the northwest, Maj. Gen. Robert Rodes's division wasn't ready to attack until Early's fight was almost over. They stopped after a short distance in the dark. Brig. Gen. Stephen Dodson Ramseur, a Confederate commander, saw that a night attack against two lines of Union soldiers behind stone walls, with cannons, would be pointless.

Losses were heavy on both sides. Col. Avery, a Confederate commander, was shot in the neck and fell from his horse. He couldn't speak, so he scribbled a note for his major: "Major, tell my father I died with my face to the enemy. I. E. Avery." He died the next day.

Day Three: Cannons Fire

On July 3, there was no infantry attack directly on Cemetery Hill. The main Confederate attacks were on Culp's Hill and another part of Cemetery Ridge. However, Union cannons on Cemetery Hill fired back at the Confederate artillery barrage that came before Pickett's Charge. They also provided support fire during the Confederate infantry attack, helping to stop it. Some historians believe that Robert E. Lee's main goal for the attacks on July 2 and 3 was actually Cemetery Hill.

After the Battle

After the battle, state militiamen stayed on East Cemetery Hill for several weeks. They set up a camp to keep the battlefield safe from looters and curious visitors. They also collected weapons and helped in the area's hospitals. Elizabeth C. Thorn, the pregnant wife of the Evergreen Cemetery keeper, along with her parents and hired helpers, dug 105 graves for soldiers killed near Cemetery Hill.

The Gettysburg National Cemetery was created in 1863, just north of Evergreen Cemetery. This is where Abraham Lincoln gave his famous Gettysburg Address.

Cemetery Hill Today

Over the years, the area around Cemetery Hill has changed. An orphanage operated at the north foot of the hill. An observation tower was built on East Cemetery Hill. Electric railways once ran on several sides of the hill. The Gettysburg National Museum also operated on the west side of Cemetery Hill for many years.

Today, the northern and western slopes of the hill are mostly filled with tourist businesses. These include hotels, restaurants, gift shops, and museums. Because of all these buildings, the important view from the hill isn't as clear as it once was.

Images for kids

-

Jubal Early's attack on East Cemetery Hill, July 2, 1863 (engraving from The Century Magazine).

-

Cemetery Hill, with a statue of General Howard at the top.