Culp's Hill facts for kids

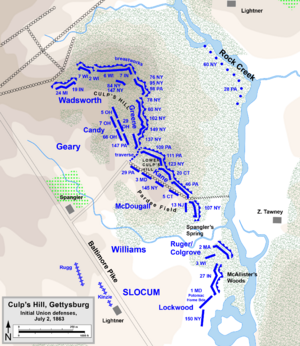

Culp's Hill, located about three-quarters of a mile south of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, was a very important place during the Battle of Gettysburg from July 1 to 3, 1863. It has two rounded peaks. The taller peak is about 630 feet above sea level. The hill was owned by farmer Henry Culp in 1863, which is how it got its name.

During the battle, Culp's Hill was a critical part of the Union Army's defense line. It was like the "barb" on a fish-hook shaped line. Even though it was heavily wooded and not good for cannons, losing it would have been a disaster for the Union army. If the Confederates had taken it, they could have easily attacked Cemetery Hill and the Baltimore Pike. The Baltimore Pike was vital for getting supplies to the Union army and for stopping any Confederate advance towards Baltimore or Washington, D.C..

Contents

The Battle Begins

First Day: A Crucial Retreat

On the evening of July 1, 1863, after a tough day of fighting, Union troops retreated and gathered on Culp's Hill and nearby Cemetery Hill. These hills became their main rallying points. Confederate General Richard S. Ewell thought Culp's Hill was empty and a good target. He believed taking it would make the Union position on Cemetery Hill impossible to hold.

However, when a small group of Confederate soldiers went to check, they ran into Union troops already there. These Union soldiers were from the 7th Indiana Infantry. The Confederates were surprised and quickly fled. General Ewell's failure to capture Culp's Hill or Cemetery Hill that evening is seen as one of the biggest missed chances of the entire battle.

Second Day: Building Strong Defenses

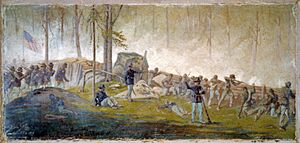

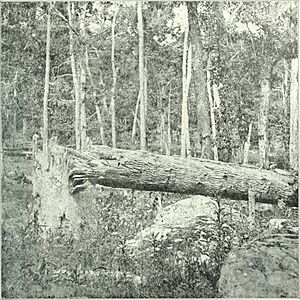

By the morning of July 2, the Union XII Corps arrived and began to fortify Culp's Hill. Brigadier General George S. Greene, who was 62 years old and the oldest Union general on the field, was a civil engineer before the war. He understood how important strong defenses were. Even though his commanders didn't think they would stay long, Greene had his troops cut down trees and gather rocks and earth to build very effective breastworks (defensive walls).

Later that morning, Confederate General Robert E. Lee ordered attacks on both ends of the Union line. General James Longstreet attacked the Union left flank. At the same time, General Ewell was supposed to make a smaller attack on the Union right, where Culp's Hill was. This was meant to distract the Union defenders.

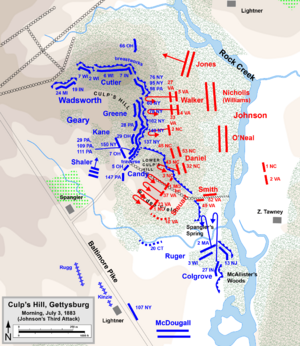

Ewell started his attack around 4 p.m. with an artillery barrage. But Union General George Meade was focused on the heavy fighting on his left flank. He ordered most of the XII Corps to move and help there. This left Greene's brigade, about 1,400 men, as the only defenders of Culp's Hill. They had to stretch their line dangerously thin.

Around 7 p.m., as it got dark, Ewell began his main infantry attack. Three Confederate brigades, about 4,700 men, charged up the eastern slope of Culp's Hill. As the fighting began, Greene asked for reinforcements. He received about 750 men from other Union corps, who helped as reserves and brought more ammunition.

The Confederate soldiers found it very difficult to climb the steep, rocky slopes and attack the strong Union breastworks. They were shocked by how well-built the defenses were. Their charges were easily pushed back by the Union soldiers, who suffered very few casualties. One Union officer wrote that without the breastworks, their line would have been "swept away in an instant."

In the darkness, some Confederate regiments managed to get around the end of the Union line. Colonel David Ireland and his 137th New York regiment were on the very edge of the Union army. They fought hard to stop this flanking attack. They were forced back a bit but held their ground, protecting the Union army's main supply road, the Baltimore Pike, which was only 600 yards away. Ireland's men prevented a huge disaster, even though their heroic defense isn't as famous as some others.

By late that night, Confederate troops had taken over some empty Union defensive lines near Spangler's Spring. This caused a lot of confusion when the rest of the XII Corps returned. Both sides decided to wait for daylight to continue the fight.

Third Day: Fierce Morning Attacks

On July 3, General Lee planned to attack Culp's Hill again, along with a major attack on Cemetery Ridge. But the Union forces on Culp's Hill didn't wait. At dawn, Union cannons opened fire on the Confederates who had captured positions. The Confederates then launched their own attacks. General Ewell tried to stop the fighting, but it was "too late to recall."

The fighting continued until late morning, with three more failed attacks by the Confederates. The Union forces had been reinforced, and General Greene used a smart tactic: he rotated his regiments in and out of the breastworks so they could reload their guns, keeping up a constant, high rate of fire.

In the final Confederate attack, around 10 a.m., they charged again, but both attacks were pushed back with heavy losses. The Union artillery also played a big role in stopping the Confederates in the open fields.

Near noon, the fighting ended with a final, desperate Union attack near Spangler's Spring. Two Union regiments, the 2nd Massachusetts and the 27th Indiana, were ordered to charge the Confederate position. With only 650 men against 1,000 Confederates behind defenses, it was a very dangerous order. One officer said, "Well, it is murder, but it's the order." Both regiments were pushed back with terrible losses.

Despite getting more troops, the Confederates were beaten back with huge losses. General Johnson's division lost about 2,000 men, nearly a third of his force. The Union XII Corps lost about 1,000 men over both days.

A Family Divided

One of the saddest stories from the battle involves the Culp family, who owned the hill. Henry Culp had two nephews, John Wesley Culp and William Culp. Wesley joined the Confederate Army, and William joined the Union Army. Wesley's regiment fought on Culp's Hill, and he was killed there on July 3, on his family's own land. William was not at Gettysburg and survived the war, but he considered his brother a traitor and never spoke of him again.

After the Battle

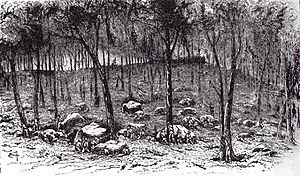

After the battle, Culp's Hill became a popular place for tourists. It was close to town, and unlike many battlefields, it was heavily wooded. The intense fighting left visible damage on the trees, with some completely cut down by bullets and cannon fire. It took over twenty years for nature to heal the scars of battle.

Today, Culp's Hill is part of the Gettysburg National Military Park. It has many monuments and an observation tower, all cared for by the U.S. National Park Service.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |