Indianapolis in the American Civil War facts for kids

Indianapolis, the capital city of Indiana, played a very important role during the American Civil War. It was a major base for the Union army, helping to supply and train soldiers. Governor Oliver P. Morton quickly made Indianapolis a central place for organizing troops. The city became a key railroad hub, moving soldiers to different battle areas.

Many military camps were set up around Indianapolis. Camp Morton, which started as a training ground in 1861, became a large prisoner-of-war camp for captured Confederate soldiers in 1862. People in Indianapolis also supported the Union by providing food, clothing, and supplies. Local doctors and nurses helped sick and wounded soldiers. The city's population grew a lot during the war, bringing new businesses and jobs. This led to Indianapolis becoming an important industrial city.

Contents

Indianapolis During the War

During the Civil War, Indianapolis was a busy place for getting troops ready. As citizens supported the Union, the city's population grew. New businesses and industries brought more jobs and helped the city grow. People faced challenges like higher prices and shortages of food and clothing. This time also saw strong disagreements between Indiana's Democrats and Republicans. The war helped Indianapolis become a modern, industrial city with strong railroad connections.

Getting Ready for War

In the winter of 1860–1861, people in Indianapolis talked about a possible war. The city had only four small groups of trained fighters. On January 7, 1861, the Indianapolis Zouaves offered to serve if the governor needed them.

On February 11, 1861, President-elect Abraham Lincoln visited Indianapolis. This was one of his stops on the way to his inauguration in Washington, D.C.. Two months later, the country was on the edge of war.

1861: The Start of the War

On April 12, news arrived that Confederate forces had attacked Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina. On April 13, two big meetings were held in Indianapolis. People agreed to support the Union. They said they would "unite as one man to repel all treasonable assaults."

On April 15, 1861, President Lincoln asked for 75,000 volunteers to join the Union Army. Governor Morton quickly offered 10,000 men from Indiana. The state's first goal was to get 4,683 men. Orders were given to make Indianapolis a place for volunteers to sign up.

On the first day, 500 men arrived in the city. Within a week, more than 12,000 recruits had signed up. This was almost three times the number needed.

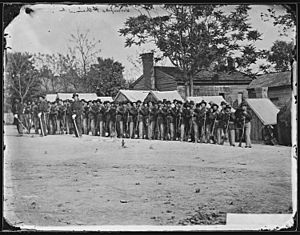

Governor Morton and Lew Wallace quickly set up Camp Morton. It was on the old Indiana State Fair grounds. This camp was the main place to organize and train Indiana's Union volunteers. The first soldiers arrived on April 17. During the war, 24 military camps were set up near Indianapolis.

On April 20, Indianapolis's city council set aside $10,000 for the war. Four days later, the Indiana General Assembly met. They gave the governor wartime powers and money for the war effort. Governor Morton also created a state-owned arsenal in Indianapolis to make ammunition. The U.S. Congress later approved a permanent federal arsenal in Indianapolis in 1862.

By April 27, 1861, Indiana's first six regiments were ready. They were all organized in Indianapolis. These included the 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th, and 11th Indiana infantry regiments.

More than 60% of Indiana's regiments were organized and trained in Indianapolis. Men from Indianapolis and Marion County, Indiana, served in 39 different regiments. About 4,000 men from Indianapolis joined the army. Around 700 of them died during the war.

The 11th Regiment Indiana Infantry, also called the Indiana Zouaves, was the first regiment to leave Indianapolis. This was on May 8, 1861. All four of Indianapolis's local fighting groups joined this regiment. Lew Wallace became a major general in the Union army. Frederick Knefler, another Indianapolis resident, became a brigadier general. He was the highest-ranking Jewish military officer in the Union.

Most Indiana regiments were formed from towns or counties. But some were based on ethnic groups. The 32nd Indiana Infantry Regiment, the first German-American regiment, formed in Indianapolis in 1861. The 35th Indiana Infantry Regiment, the first Irish-American regiment, also formed here.

Most people in Indianapolis strongly supported the Union. Sometimes, pro-Union crowds would make people suspected of supporting the Confederacy take an oath of loyalty.

1862: A City Transformed

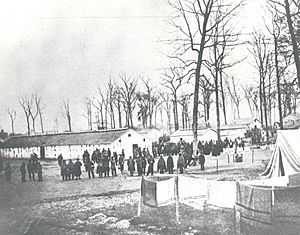

Union troops continued to train in Indianapolis. Battles in Kentucky and Tennessee brought big changes. After some major battles, the Union began capturing many Confederate prisoners. Governor Morton offered to hold some in Indianapolis. Camp Morton was then turned into one of the Union's largest prisons for Confederate soldiers.

The first Confederate prisoners arrived at Camp Morton on February 22–23, 1862. Many of them were sick and didn't have enough warm clothes. Indianapolis citizens helped by providing food, clothing, and supplies. Local doctors and women helped care for the sick prisoners. Two local buildings were even turned into hospitals for them. For the rest of the war, Camp Morton usually held between 3,000 and 6,000 prisoners.

Union soldiers continued to gather in Indianapolis, sometimes as many as 12,000 at once. New regiments formed in 1862 included the 70th Indiana Infantry Regiment and the 79th Indiana Infantry Regiment. Popular places for soldiers were Monument Circle and University Park.

A Soldiers' Home and a Ladies' Home were set up in Indianapolis in 1862 and 1863. These homes provided housing and food for soldiers and their families passing through the city. Citizens kept helping Union soldiers with supplies. Aid societies and the Indiana Sanitary Commission raised money and gathered supplies for troops. Women in Indianapolis also formed groups to provide blankets and clothing for soldiers.

There was a lot of street crime in Indianapolis during the war. The city increased its police force. Local businesses hired private security. Guards were placed at Indianapolis Union Station to help with law and order. Fights, robberies, gambling, and drunkenness became big problems.

Several Indiana hospitals cared for wounded soldiers, including Indianapolis City Hospital. Governor Morton also started recruiting women to work as nurses in military hospitals.

The city was also home to Richard Jordan Gatling, who invented the Gatling gun. This hand-cranked, rapid-fire gun was tested in Indianapolis in 1862. It was an early version of the modern machine gun.

1863: Worries and Raids

Political differences between Democrats and Republicans caused many Hoosiers to be suspicious. They feared secret groups that might support the South. In May, during the Indianapolis city election, the Democrats pulled out of the race. Only 14 votes were cast for Democratic candidates.

Before a state Democratic convention in May, rumors spread. Some believed that members of a secret society planned to attack Camp Morton and the state arsenal. Soldiers were sent to guard the city and government buildings.

On May 20, Union soldiers tried to stop the convention. Men were arrested for carrying hidden weapons. After the convention, soldiers stopped and searched two trains leaving the city. They demanded that passengers give up their weapons. Soldiers took "several hundred" weapons. Passengers also threw weapons into Pogue's Run, a nearby creek. This event was later called the Battle of Pogue's Run. It didn't cause serious trouble, but it showed how strong the political fights were. Republicans used the seized weapons to claim Democrats were disloyal.

Rumors of plots against the government continued that summer. On July 8, 1863, Confederate general John Hunt Morgan crossed the Ohio River. Indiana went into a state of emergency. Just the day before, Indianapolis citizens were celebrating Union victories. But then panic spread as Morgan's troops seemed to be heading toward Indianapolis. Many feared Morgan would attack the city and free the Confederate prisoners at Camp Morton.

Morgan's telegraph operator, "Lightning" Ellsworth, sent false messages. He made it seem like Morgan had many more men and would attack Indianapolis. Within 48 hours, about 65,000 Indiana volunteers gathered to fight. Five regiments were ready to defend the state capital at the Indiana Statehouse. The tension ended on July 14, when it was confirmed Morgan had left Indiana.

1864: New Regiments and Trials

New regiments continued to form in Indianapolis. The 28th Regiment United States Colored Troops was the only black regiment formed in Indiana during the war. It trained at Camp Fremont. This regiment had 518 men and lost 212 before the war ended.

Indianapolis's "City Regiment" formed in May 1864. It was called the 132nd Indiana Infantry Regiment. This regiment guarded railroads in Tennessee and Alabama. This freed up regular army troops for fighting. The 132nd Indiana was made up mostly of young boys and older men. It was very popular with Indianapolis citizens.

In September 1864, Indianapolis was the site of trials for men accused of treason. In a famous case called Ex parte Milligan, the U.S. Supreme Court later said these military trials were illegal. This was because civilian courts were still open during the war. The men were released in 1866.

1865: The War Ends

News of Confederate General Robert E. Lee's surrender reached Indianapolis on April 9, 1865. This caused huge public celebrations. But the joy turned to sadness when news of President Lincoln's assassination arrived on April 15. Lincoln's funeral train passed through the city on April 30. About 100,000 people waited in long lines to see Lincoln's coffin at the Indiana Statehouse.

Indianapolis saw a lot of activity as military forces left at the end of the war. The last military troops organized in Indianapolis were the 156th Indiana Infantry Regiment. In June, formal parties honored soldiers returning home. On June 12, the last Confederate prisoner was released from Camp Morton. By the autumn of 1865, the city's Soldiers' Home and Ladies' Home closed. Most military camps also closed after the soldiers left.

After the War

Indiana's economy got much better after the war, especially in Indianapolis. The city's population grew from 8,000 in 1850 to 45,000 by the end of 1864. By 1880, it was over 75,000. The war led to a real-estate boom. New neighborhoods like Irvington and Woodruff Place were built.

As the city grew, it needed better public services. Street railways came in the 1860s. The first sewage system was built in 1869. Most downtown streets had gaslights by 1870. Water from a central system reached homes in 1871. Health care also improved. Indianapolis City Hospital began treating regular patients in 1866.

More factories and industries after the war brought new wealth. By 1880, Indianapolis was Indiana's main business and industry center. New businesses included meat-packing plants and foundries. In 1876, Colonel Eli Lilly opened his pharmaceutical lab, which became Eli Lilly and Company. Indianapolis also continued to grow as a transportation hub. Railroad lines expanded, connecting the city to places across the country.

People in Indianapolis continued to help those in need. Programs started to help wounded soldiers with housing and food. New orphanages and homes were created to help women and children. The German Protestant Orphans' Association started in 1867. The Indianapolis Asylum for Friendless Colored Children, the only orphanage for African American children in the state, opened in 1870.

After the war, Indiana became a key "swing state" in national elections. This meant it often helped decide who would win the presidency. Benjamin Harrison, an Indianapolis lawyer and former Union army officer, was elected the 23rd president of the United States in 1888.

Memorials and Tributes

In 1866, Crown Hill National Cemetery was created within Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis. It is one of two national military cemeteries in Indiana from the war. That same year, Union soldiers buried elsewhere in the city were moved to Crown Hill.

In November 1866, Indianapolis hosted the first national meeting of the Grand Army of the Republic. This group honored Civil War veterans.

The Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument in downtown Indianapolis was built to honor Indiana's Civil War veterans. Construction began in 1888 after many years of discussion. The monument was finished in 1901 and dedicated on May 15, 1902.

The Confederate Soldiers and Sailors Monument was built in 1912. It honored 1,616 Confederate soldiers buried in a mass grave at Greenlawn Cemetery. When these soldiers were moved to Crown Hill National Cemetery starting in 1928, the monument was moved to Garfield Park.

Images for kids

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |