Missouri in the American Civil War facts for kids

During the American Civil War, Missouri was a very important border state. It had people who supported both the Union (North) and the Confederacy (South). Missouri sent soldiers, generals, and supplies to both sides. It even had a star on both flags and two different governments! The state also suffered a terrible war within its own borders, with neighbors fighting neighbors.

Missouri had been a slave state since 1821. Its location in the middle of the country made it a battleground for different ideas. When the war started in 1861, controlling the Mississippi River and the growing city of St. Louis became very important. This made Missouri a key area in the western part of the war.

By 1865, about 110,000 Missourians had fought for the Union Army. At least 40,000 joined the Confederate Army. Many also fought as "bushwhackers," who were pro-Confederate fighters. The war in Missouri lasted from 1861 to 1865. Battles and small fights happened all over the state. Missouri saw more than 1,200 separate fights. Only Virginia and Tennessee had more.

The first big Civil War battle west of the Mississippi River happened on August 10, 1861. It was the Battle of Wilson's Creek in Missouri. The largest battle west of the Mississippi River was the Battle of Westport in Kansas City in 1864.

Contents

Why Missouri Was Important

The Missouri Compromise

Many early settlers in Missouri came from the Southern states. They traveled up the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. Many of them brought slaves with them. Missouri became a slave state in 1821. This happened after the Missouri Compromise of 1820. In this agreement, Congress said slavery would be illegal north of a certain line, except in Missouri. To keep things balanced, Maine joined the Union as a free state. Henry Clay helped create this compromise.

Bleeding Kansas: A Violent Preview

The Underground Railroad was a secret network of safe places. Runaway slaves used it to find safety as they headed north. Slave owners in Missouri worried that if nearby areas became free states, it would be easier for slaves to escape.

In 1854, the Kansas–Nebraska Act changed the Missouri Compromise. It allowed the Kansas and Nebraska Territories to vote on whether they would be free or slave states. This led to a real fight between pro-slavery people from Missouri, called "Border Ruffians," and anti-slavery "Free-Staters" from Kansas. Both groups wanted to control how Kansas joined the Union. This conflict included attacks and murders on both sides. Famous events were the Sacking of Lawrence by pro-slavery forces and the Pottawatomie massacre led by abolitionist John Brown. Kansas first approved a pro-slavery constitution. But the U.S. Congress rejected it. Kansas then approved an anti-slavery constitution and joined the Union in January 1861. The violence along the Kansas–Missouri border was a sign of the bigger war to come. It actually continued throughout the Civil War.

The Dred Scott Decision

While "Bleeding Kansas" was happening, a very important court case was decided. Dred Scott, a slave, had sued for his family's freedom in St. Louis in 1846. His case reached the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1857, the Supreme Court made a shocking decision. They ruled that slaves were not automatically free just by entering a free state. Even more, they said that no person of African descent could be a U.S. citizen. This meant African-Americans could not use the courts to fight for their rights. This decision angered abolitionists across the country. It added to the strong feelings that led to the Civil War.

Missouri Tries to Stay Neutral

By 1860, Missouri's population had changed. Many new people had moved in who did not own slaves. These included people from Northern states and immigrants from Germany and Ireland. As war seemed likely, Missouri hoped to stay out of the fighting. It wanted to remain part of the Union but be militarily neutral. This meant not sending soldiers or supplies to either side. It also meant fighting any troops from either side who entered the state.

This idea was first suggested by Governor Robert Marcellus Stewart. The new governor, Claiborne Fox Jackson, also supported it. However, Jackson also said that if the federal government forced Southern states to stay, Missouri should support its "sister southern states." A special meeting was held to talk about secession (leaving the Union). The delegates voted to stay in the Union and supported neutrality.

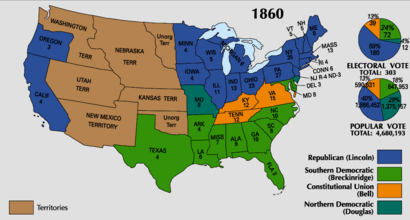

In the 1860 presidential election, Abraham Lincoln received only a small number of votes in Missouri. Most Missourians voted for candidates who wanted to keep things as they were.

War Begins in Missouri

Governor Jackson's Plans

In 1860, Claiborne Fox Jackson became Missouri's new governor. He was a strong supporter of the South. Even though he had campaigned for peace, Jackson secretly worked to make Missouri leave the Union. He planned to take over the federal arsenal (a place where weapons are stored) in St. Louis. He also tried to get money from banks to arm state troops, even though the state assembly had refused this idea.

The Camp Jackson Affair

Missouri's neutrality was quickly tested. The federal government sent more soldiers to the St. Louis Arsenal. Another federal arsenal in Missouri had already been captured by pro-Confederate groups. Governor Jackson was rumored to be planning to attack the St. Louis Arsenal to get its 39,000 guns. So, the Secretary of War ordered Captain Nathaniel Lyon to move most of the weapons out of the state. On April 29, 1861, 21,000 guns were secretly moved to Illinois.

At the same time, Governor Jackson called up the Missouri State Militia for training near St. Louis. Lyon saw this as a threat to take the arsenal. On May 10, 1861, Lyon attacked the militia. He marched them as prisoners through the streets of St. Louis. A riot broke out. Lyon's troops, many of whom were German immigrants, fired into the crowd. Twenty-eight people were killed, and 100 were injured.

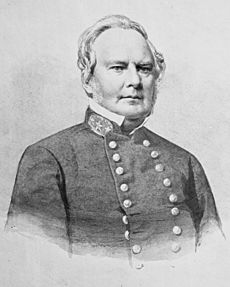

The next day, the Missouri General Assembly allowed the creation of a Missouri State Guard. Major General Sterling Price was put in charge. This guard was meant to fight off invasions from either side. The federal commander, William S. Harney, tried to calm things down. He agreed to Missouri's neutrality in the Price-Harney Truce. But President Lincoln did not agree. He removed Harney and put Lyon in command.

On June 11, 1861, Lyon met with Governor Jackson and Price. They talked about keeping the truce. But they quickly disagreed about who had power. Jackson wanted federal forces to stay only in St. Louis. He also wanted pro-Union groups in Missouri to be disbanded. Lyon refused. He said that if Jackson insisted on limiting the federal government's power, "This means war." After this, Lyon began to chase Jackson and Price and their state government. This led to battles like the Battle of Boonville and the Battle of Carthage. Jackson and other pro-Confederate politicians fled to the southern part of the state. They eventually set up a government-in-exile and voted to leave the Union. However, this government did not control any part of Missouri.

Missouri's New Government

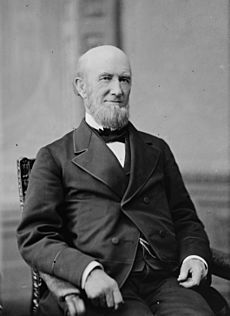

On July 22, 1861, Lyon captured Missouri's capital, Jefferson City. A special meeting then declared the governor's office empty. On July 28, they appointed Hamilton Rowan Gamble as the new governor. This new government agreed to send troops to Lincoln. They began forming new pro-Union regiments. By the end of the war, about 447 Missouri regiments had fought for the Union.

Confederate Government in Exile

In October 1861, the pro-Southern state leaders, including Jackson and Price, met in Neosho. They formally voted to secede from the Union. This gave them votes in the Confederate Congress. But it was mostly symbolic, as they did not control the state. This exiled government had to move its capital to Texas. When Jackson died in 1862, his lieutenant governor, Thomas Caute Reynolds, took over.

Early Battles (1861–1862)

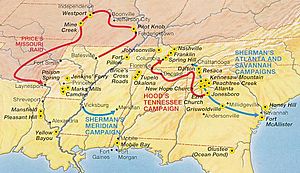

Military actions in Missouri generally happened in three stages. First, the Union removed Governor Jackson and chased Sterling Price in 1861. Second, there was a period of "bushwhacking" guerrilla fighting from 1862 to 1864. This continued even after the war ended elsewhere. Third, Sterling Price tried to take back the state in 1864.

Fighting for Control of Missouri

The biggest battle to remove Jackson was the Battle of Wilson's Creek near Springfield, Missouri, on August 10, 1861. This was the first time the Missouri State Guard fought alongside Confederate forces. Over 12,000 Confederate and Arkansas soldiers and Missouri State Guardsmen fought about 5,400 Union soldiers. The battle lasted six hours. Union forces lost over 1,300 men, including Lyon, who was killed. The Confederates lost 1,200 men. The Confederates were too tired to chase the retreating Union forces. After the battle, the Southern commanders disagreed. Price wanted to invade Missouri. But others worried about supplies and the safety of Arkansas. So, the Confederate and Arkansas troops went back to the border. Price led his Guardsmen into northwestern Missouri to try and take back the state.

Price's Missouri State Guard then marched on Lexington. They surrounded Colonel James A. Mulligan's Union soldiers at the Siege of Lexington from September 12–20. The rebels used wet hemp bales as moving shields to protect themselves from fire. By September 20, they were close enough to capture the Union defenses. Mulligan surrendered. This was a big success for the rebels. It meant they had control, for a short time, in western and southwest Missouri.

However, this rebel success in Missouri did not last long. General John C. Frémont quickly moved to retake Missouri. On September 26, Frémont moved west from St. Louis with a large army. He threatened to trap Price's rebels. On September 29, Price had to leave Lexington. He and his men moved into southwest Missouri. They soon retreated from the state and went to Arkansas and later Mississippi.

Small groups of the Missouri Guard stayed in the state and fought isolated battles. Price soon came under the direct command of the Confederate Army. In March 1862, a Union victory at the Battle of Pea Ridge in Arkansas ended hopes for a new Confederate attack in Missouri.

Frémont's Emancipation Order

John C. Frémont took over as commander of the western area. After the Battle of Wilson's Creek, he declared martial law in Missouri. He also issued an order freeing the slaves of Missourians who were fighting against the United States. This order said that the property of people fighting against the U.S. would be taken. And their slaves would be set free.

This was not a full emancipation for all slaves in the state. It only applied to slaves owned by people who were rebelling. But it went further than what Congress had allowed. President Lincoln worried this order would anger neutral Missourians and slave states that were still in the Union. So, he asked Governor Gamble to cancel the emancipation order and ease martial law.

River Warships and Campaigns

While battles were happening on land, a special effort built a fleet of warships for the rivers. James Buchanan Eads, an engineer from St. Louis, built shallow-draft ironclads for use on the western rivers. He worked closely with Army and Navy officers. Eads used his reputation and money to build nine ironclads in just over three months. These were the first U.S. ironclads and the first to fight in battle.

St. Louis became a gathering place for western troops. In February 1862, General Henry Halleck approved a joint invasion of west Tennessee. Union troops under General Ulysses S. Grant, along with the new Western Gunboat Flotilla, captured Fort Henry and Fort Donelson. This broke the Confederate defenses in the west. After the Battle of Shiloh, the Union Army pushed into northern Mississippi. The gunboat fleet moved down the Mississippi River, capturing every Confederate position north of Vicksburg, Mississippi.

This river strategy put the Confederacy on the defensive in the west for the rest of the war. It effectively ended Confederate efforts to retake Missouri. The defeat of the Confederate army at the Battle of Pea Ridge in Arkansas also discouraged Confederate leaders from trying to occupy Missouri. Later Confederate actions in the state were limited to a few large raids and supporting Missouri guerrillas.

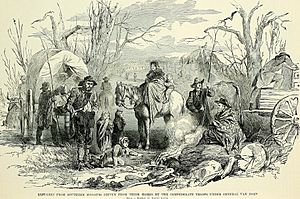

Helping Soldiers and Refugees

During the war, thousands of black refugees came to St. Louis. Groups like the Western Sanitary Commission and the American Missionary Association set up schools for their children.

The Western Sanitary Commission was a private group in St. Louis. It helped the U.S. Army care for sick and wounded soldiers. It was started in August 1861 to help after the first battles. It raised money from private donations. It selected nurses, provided hospital supplies, set up hospitals, and prepared hospital ships. It also gave clothes and places to stay for freed slaves and refugees. It set up schools for black children. This group continued to fund projects until 1886.

Guerrilla Warfare (1862–1864)

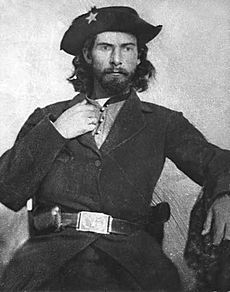

After the Battle of Wilson's Creek, there were no more large battles in Missouri until 1864. During this time, the state saw widespread guerrilla warfare. Southern partisan rangers and bushwhackers fought against Kansas-based fighters called Jayhawkers and Redlegs.

Jayhawker raids against people thought to be Confederate supporters made Missourians angry. This made it harder for the Union government to keep peace. Bushwhackers also caused violence and robbed people, especially in northern Missouri. These fights were often neighbor against neighbor. Civilians on all sides faced looting and violence.

Some of the most famous bushwhackers were William C. Quantrill's raiders, William "Bloody Bill" Anderson, and a young Jesse James.

General Order No. 11

In 1863, after the Lawrence Massacre in Kansas, Union General Thomas Ewing Jr. blamed farmers in rural Missouri. He said they either started the massacre or supported it. He issued General Order No. 11. This order forced all residents of four counties in western Missouri to leave their homes. Their property was then burned. The order applied to all farmers, even those loyal to the Union. Those who could prove their loyalty could stay in certain towns. Others were forced to leave the area completely.

Later Battles (1864–1865)

Price's Missouri Expedition

By 1864, the Confederacy was losing the war. Sterling Price brought his Missouri Guard back together. He launched a final attack to try and take Missouri. But Price could not repeat his earlier victories. He tried to capture Fort Davidson but failed. Then, Price wanted to attack St. Louis. But it was too strongly defended. So, he moved west, following the Missouri River. This took him through areas friendly to the Confederacy. Even though Price ordered his men not to steal, many pro-Confederate civilians in this area suffered from looting by Price's soldiers.

Union forces tried to slow Price's advance with smaller fights and bigger battles. Price eventually reached the far western part of the state. He fought in a series of tough battles. His Missouri campaign ended with the Battle of Westport. Over 30,000 troops fought in this battle, and Price's army was defeated. Price's Confederates retreated through Kansas and into Arkansas. They stayed there for the rest of the war.

After the War

Missouri stayed in the Union. So, it did not have an outside military occupation like other slave states during the Reconstruction era. After the war, Republicans controlled the state government. They tried to rebuild Missouri. They stopped former Confederate supporters from being involved in politics. They also tried to give more power to the state's newly freed African-American population. This made many powerful groups unhappy.

By 1873, Democrats became the main power in the state again. They joined with former Confederates. The reunited Democratic Party used ideas of racial prejudice. They also promoted their own version of the South's "Lost Cause." This story said that Missourians were victims of the federal government. It also called Missouri Unionists and Republicans traitors and criminals. This way of telling history was very successful. It helped the Democratic Party control the state until the 1950s. This return of ex-Confederates and Democrats also stopped efforts to empower African-Americans in Missouri. It brought in Missouri's version of Jim Crow laws, which were unfair laws against black people.

Many newspapers in Missouri in the 1870s strongly opposed the national Republican policies. The famous James-Younger gang used this to their advantage. They became folk heroes as they robbed banks and trains. They received sympathetic news coverage from state newspapers. Jesse James, who had fought as a bushwhacker, even tried to excuse a murder during a bank robbery by saying he thought he was killing someone who had hunted down his old commander.

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |