Battle of Westport facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Westport |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War |

|||||||

Westport Battlefield |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Army of the Border | Army of Missouri | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 22,000 | 8,500 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| about 1,500 | about 1,500 | ||||||

The Battle of Westport was a very important fight during the American Civil War. It happened on October 23, 1864, in what is now Kansas City, Missouri. Some people call it the "Gettysburg of the West" because it was a major turning point.

In this battle, Union forces led by Major General Samuel Ryan Curtis won a big victory. They defeated a smaller Confederate army led by Major General Sterling Price. This defeat forced Price's army to retreat and ended the last major Confederate attack west of the Mississippi River. After this battle, the Union Army kept strong control over most of Missouri for the rest of the war. More than 30,000 soldiers fought here, making it one of the largest battles west of the Mississippi River.

Contents

Westport: A Historic Town

Westport is now part of Kansas City, Missouri. It was already an important place before the battle in 1864. A man named John Calvin McCoy, known as the "Father of Kansas City," helped plan the town. Many pioneers traveling west on trails like the Oregon, California, and Santa Fe Trail passed through Westport. Over time, Westport became the main starting point for these western journeys, which helped the town grow.

During the Civil War, nearby Kansas City was the main base for the Union's "District of the Border." It had many Union soldiers stationed there. Even though Westport was becoming less important than Kansas City, it was still a key spot in the area. The battle happened here not because of the town's importance, but because of a series of events that led the armies to clash in this specific location.

Price's Raid: The Start of the Conflict

In September 1864, Confederate Major General Sterling Price led his Army of Missouri into Missouri. He hoped to capture the state for the South. He also wanted to make people in the North turn against Abraham Lincoln in the 1864 presidential election.

Major General William Rosecrans, who commanded the Union forces in Missouri, began gathering troops to stop Price's invasion. Rosecrans sent his cavalry, led by Major General Alfred Pleasonton, to chase Price. A large group of infantry soldiers from the Army of the Tennessee, led by Andrew Jackson Smith, also joined the chase.

After losing a battle at Fort Davidson, Price realized that St. Louis was too strongly defended for his army of 12,000 men. So, he turned west to threaten Jefferson City. After some small fights there, Price decided that Jefferson City was also too well-defended. He then moved even further west toward Fort Leavenworth. As he marched, Price's army got smaller. Many soldiers got sick, left the army, or were lost in battles. His force shrank to only 8,500 men.

The Union Responds to the Threat

Major General Samuel Ryan Curtis, who commanded the Union forces in Kansas, now faced the danger of Price's army moving into his area. He learned about the Confederate movements from spies, including Wild Bill Hickok. Curtis quickly gathered his troops and called them the Army of the Border.

James G. Blunt was called back from fighting Native American groups to lead the first division of this army. His division was mostly made up of volunteer soldiers and some Kansas militia. At first, Curtis could only gather about 4,000 volunteers. He asked the Kansas governor, Thomas Carney, to call out the state militia to make his forces stronger.

Governor Carney was worried that Curtis was trying to pull the militia away from their homes right before election time. He didn't think Price's army in Missouri was a threat to Kansas. However, once Price turned west toward Jefferson City, Carney agreed. Major General George Dietzler then took command of a division of Kansas Militia, which joined Curtis's Army of the Border.

Battle Preparations

General Curtis sent most of his first division, led by General James Blunt, to meet the Confederates at Lexington. This town was about forty miles east of Kansas City. Blunt couldn't stop Price there, but he did slow him down and gathered important information about the Confederate forces.

Again, at the Little Blue River on October 21, Blunt had to retreat. But he slowed Price enough for a Union cavalry division, led by Alfred Pleasonton, to catch up to the Confederates. More fighting happened the next day at Independence, where Price won again.

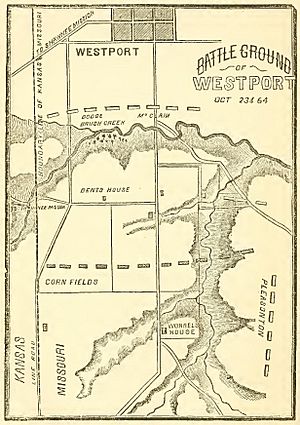

Curtis was almost sixty years old and not eager for more fighting. However, thanks to his aggressive officer, General Blunt, Curtis decided to make another stand. This time, it would be south of Westport. Blunt personally oversaw the building of a defensive line south of the town. This line was along Brush Creek, stretching toward the Kansas state line.

Price knew that the Union forces in front of him and behind him outnumbered him almost three to one. So, he decided to attack them one at a time. He chose to attack Curtis's army at Westport first. Price, who was also almost as old as Curtis, let his officer, General Jo Shelby, lead the battle.

Price's army had about 500 wagons and 5,000 cattle. He first needed a place for his supply trains to cross the Blue River near Westport. One of Price's divisions, led by John S. Marmaduke, forced a crossing at Byram's Ford on October 22nd. They then set up positions on the west bank to hold off Pleasonton's Union Cavalry, who were now threatening Price's rear. Two other Confederate divisions, led by Shelby and James Fagan, were ready to attack Blunt along Brush Creek the next day. They hoped to defeat Blunt before Pleasonton's full force could arrive.

The Battle of Westport Begins

Action at Brush Creek

Blunt expected Price's attack. He placed his three available brigades along Brush Creek. A fourth brigade, led by Colonel Charles Blair, was on its way from Kansas City. East of Wornall Lane (now Wornall Road) was the brigade of J. Hobart Ford. West of Wornall was the brigade of Charles "Doc" Jennison, with artillery support. Two cavalry regiments filled the space between Jennison and the Kansas/Missouri state line. At a right angle to Jennison was the brigade of Thomas Moonlight, running parallel to the state line. Moonlight was ready to either help Jennison or attack the Confederate side.

At daybreak on October 23rd, Blunt started the battle. He sent Jennison and Ford across the icy Brush Creek with their skirmishers (small groups of soldiers). The Union forces advanced up a ridge and met the Confederates in an open field to the south.

The Confederate divisions of Joseph O. Shelby and James Fagan had orders from Price to keep Curtis busy in front of Westport. Shelby counterattacked with his famous Iron Brigade, led by M. Jeff Thompson. This attack pushed the Union soldiers back across the creek. Moonlight's brigade was hit so hard that it had to fall back to higher ground on Brush Creek's west bluff. Jennison's brigade retreated almost to the streets of Westport. At this point, it looked like the Confederates might win the day.

But the battle was not over. Shelby's force was running out of ammunition. At this important moment, Colonel Blair's brigade arrived. Curtis also heard Pleasonton's cannons firing at the Confederates at nearby Byram's Ford. Feeling more hopeful, the Union commander rode to the front lines. He personally directed Blair's troops into battle west of Jennison. The stronger Union forces charged across the creek again, with Blair leading. But they were pushed back once more and retreated to the north bank.

Curtis needed a different plan than just frontal attacks. He decided to look for a weak spot in the Confederate lines. His scouts found a local farmer named George Thoman. Thoman was eager to help the Union soldiers because the Confederates had taken his horse the night before. Thoman showed Curtis a gulch, a small valley cut by Swan Creek. This gulch led up to a hill along Shelby's left side. Curtis personally led his headquarters escort and the 9th Wisconsin Battery through this gully.

Meanwhile, Blunt kept pushing Jennison and Ford up the hill across Brush Creek. They made slow progress until the 9th Wisconsin Battery opened fire on the Confederate side and rear. Encouraged, Blunt's men now poured over the ridge. Shelby's men fought back bravely, and a back-and-forth battle happened in the open field. The Union army slowly gained the upper hand, pushing Shelby's brigades back toward the Wornall House.

Fight for the Fords

While Shelby and Fagan were having trouble, Price's rearguard, led by Marmaduke, faced a similar situation at Byram's Ford. A division of Price's army under General Shelby had forced a crossing at the ford on October 22nd, the day before the main battle. This made the Union defenders there retreat to Westport. Shelby's fellow general, Marmaduke, then set up his own defensive line on the west bank of the river. He aimed to hold off Pleasonton's cavalry, who were pushing hard from the east. If Pleasonton could force his way across the Blue River, he would be able to threaten Price's army and his supplies.

Marmaduke's division was attacked by three of Pleasonton's brigades starting at 8:00 AM on October 23rd. The Confederates managed to hold their ground at first. One of the Union brigade commanders, Brig. Gen. Egbert B. Brown, stopped his attack and was arrested by Pleasonton for not following orders. Another of Pleasonton's brigade commanders, Colonel Edward F. Winslow, was wounded. He was replaced by Lt. Col. Frederick Benteen, who would later become famous at Little Bighorn.

Despite these problems, Union soldiers reached the west bank by 11:00 AM, and Marmaduke retreated. As Brown's brigade (now led by Colonel John F. Philips) crossed the river, they came under heavy fire from Marmaduke's artillery. Once they had crossed, they charged Marmaduke across an open field. During this charge, Union troops from Missouri and Arkansas fought against Confederates from the same two states. Marmaduke was forced back, joining Shelby and Fagan. Blunt then pounded the combined Confederate forces with his own cannons.

While the main Confederate army was being attacked from two sides, Pleasonton's fourth brigade, led by Brig. Gen. John McNeil, moved against a Confederate brigade under William Lewis Cabell. This brigade was guarding a second ford near Hickman Mills. McNeil's brigade was able to drive the Confederates from the ford and cross the river. Union forces were now closing in on Price from three different directions.

Confederate Retreat

The Confederates pulled back to their last line of defense, along the road south of Forest Hill (now Gregory Boulevard). Colonel Jennison led the Union pursuit. By now, thirty Union cannons were firing at the single remaining Confederate cannon. One Union battery had just set up when Colonel James H. McGhee's Arkansas Cavalry charged down Wornall's Lane. They tried to capture the Union battery.

Captain Curtis Johnson of the 15th Kansas Cavalry saw the Confederate attack forming. He immediately moved to stop it. Johnson and McGhee fought each other with their revolvers. Both commanders were badly wounded but survived. The fight continued until Union reinforcements arrived and secured the battery.

Shelby sent a brigade under Colonel Sidney D. Jackman to protect his wagon trains. But General Price had already ordered these trains to be moved. Jackman was instead met by General Fagan, who told him about the large Union cavalry force (Pleasonton's) that had just crossed the Big Blue River to the east.

Seeing Pleasonton so close to the Confederate side and rear, General Curtis ordered a general advance of the entire Union line. Blair's and Jennison's brigades led the charge. Shelby, meanwhile, only had Thompson's Iron Brigade to hold off this massive attack. When one of Pleasonton's artillery batteries arrived to support Curtis's men, Thompson's Confederates finally broke and ran.

Price's men set fire to prairie grass in the area. This created a smoke screen to hide their retreat. Witnesses said that the road was covered with items left behind by the fleeing Confederate army.

The next day, Blunt and Pleasonton continued to chase Price's remaining forces. They chased Price through Kansas and southern Missouri, fighting him at the Marais des Cygnes, Mine Creek, the Marmiton River, and finally at Newtonia. These battles forced Price to retreat into Indian Territory. From there, he eventually returned to Arkansas through Texas. Price's campaign officially ended on November 1, 1864, with less than 6,000 survivors from his original force of 12,000.

Aftermath of the Battle

The Battle of Westport was one of the biggest battles fought west of the Mississippi River, with over 30,000 soldiers involved. The Union victory ended Price's plan to capture Missouri. Because of this, the battle is often called "The Gettysburg of the West." After the battle, Curtis wrote that the victory at Westport was "most decisive." This important border state was now firmly under Union control and stayed that way until the end of the war.

Even though Union forces never captured Price or the remains of his army, they did make the Army of Missouri unable to fight any more major battles. Price's campaign was the last big one in the Trans-Mississippi Theater.

Historians have studied the number of soldiers lost in the fighting around Westport. While some sources say about 3,000 soldiers were lost in total (1,500 Union and 1,500 Confederate), newer research suggests lower numbers for October 23rd. One estimate is that Union forces lost 361 soldiers, and Confederates lost 510 soldiers (killed, wounded, or captured) on that day.

Famous People Who Fought at Westport

Many people who fought in the Battle of Westport later became famous in other ways, especially in the American Old West.

- Buffalo Bill Cody was a private soldier in the 7th Kansas Cavalry.

- Wild Bill Hickok worked as a scout for General Curtis.

- Frederick Benteen, who took command of a brigade at Byram's Ford, later fought with George Custer at the Battle of Little Bighorn.

- The mountain man John "Liver Eating" Johnson (also known as Jeremiah Johnson) fought for the Union at Westport.

Three Union officers at Westport later became state governors:

- Samuel J. Crawford became governor of Kansas.

- John Lourie Beveridge became governor of Illinois.

- Thomas Theodore Crittenden became governor of Missouri. He was later buried in Forest Hill Cemetery, a place where fighting happened during Price's retreat.

Other important people included:

- Kansas State Treasurer David H. Heflebower, who was in the Kansas Militia.

- Future U.S. Senators Preston B. Plumb and Edmund G. Ross, who were Union officers.

- Former lieutenant governor Thomas C. Reynolds joined General Price's staff, hoping Price would capture Jefferson City and make him governor of a Confederate Missouri.

- Price himself had been a governor before the war.

- Marmaduke later became a post-war governor of Missouri.

Memorials and Preservation

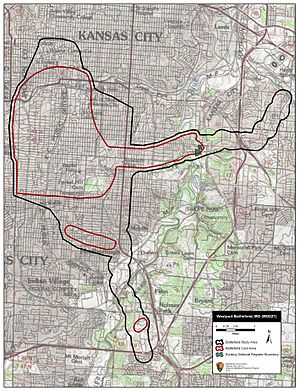

Today, you can find many signs and markers in Kansas City that remember the Battle of Westport. The main battle monument is in the Sunset Hill neighborhood, just south of the Country Club Plaza. The main battlefield includes Loose Park and part of The Pembroke Hill School. The memorial is at the southern end of Loose Park, along West 55th Street.

The Battle of Westport Museum & Visitor Center, located in Swope Park, shows what soldiers and civilians experienced during the three days of the battle.

There is also a Battle of Westport Driving Tour. It starts in Westport at Kelly's Westport Inn, the oldest building in Kansas City, Missouri. The tour has a series of signs at each stop. These signs give detailed history and directions to the next stop. Stops include the Wornall House, which was a hospital during the battle, and Forest Hill Cemetery. Many Confederate soldiers and officers, including General Joseph Shelby, are buried at Forest Hill Cemetery.

The Trailside Center museum in Kansas City also has exhibits and research materials about the battle.

Saving the Battlefield

Efforts to remember the Battle of Westport began in the early 1900s. In 1906, local historian Paul Jenkins published his book Battle of Westport. In 1912, the Byram's Ford battle was re-enacted in Swope Park. In the 1920s, leaders like H. H. Crittenden tried to save the battle sites near Loose Park and Byram's Ford. Crittenden's father, Colonel Thomas Crittenden, led a Union cavalry brigade at Byram's Ford and later became governor of Missouri.

Kansas City's mayor and council passed laws to recognize these sites. In 1924, a bill was introduced in the United States Congress to create a National Military Park. This effort failed, and memorial work stopped for several years. In the 1950s, much of the battlefield was changed by new buildings. However, one developer did put up a memorial near the historic Byram's Ford Road.

In 1958, before the 100th anniversary of the Civil War, the Civil War Round Table of Kansas City was formed. Former President Harry S. Truman was a founding member. Dr. Howard N. Monnett, a member of this group, researched and wrote a lot about the "action before Westport." His book was published in 1964 for the battle's 100th anniversary.

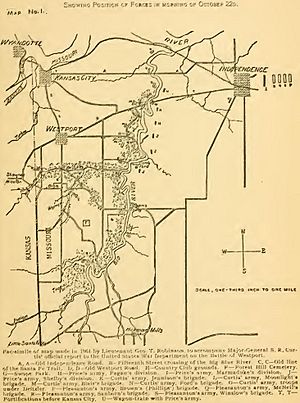

Dr. Monnett's passion led to the creation of a driving tour of the battle sites. By 1979, the Monnett Fund had raised money to put up permanent markers at 25 sites. They also created a self-guided car tour. These markers included a monument at the meadow site and several signs on nearby Bloody Hill. The battlefield was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1989. This happened after the Fund bought 50 acres (200,000 m²) of the Westport battlefield, including the Byram's Ford site itself. The land was given to the Kansas City Parks Department in April 1995. In 1996, archaeological studies found artifacts from the battle in and around the Byram's Ford area.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Westport para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Westport para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |