Second Battle of Lexington facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Second Battle of Lexington |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Price's Raid during the American Civil War |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Sterling Price | James G. Blunt | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Army of Missouri | Two brigades of Blunt's division | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| c. 13,000 | 2,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| light | c. 40 | ||||||

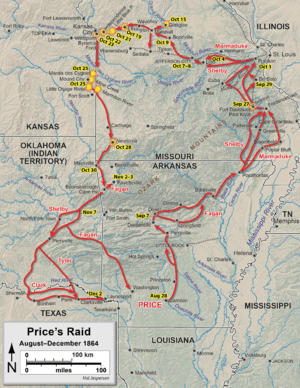

The Second Battle of Lexington was a smaller fight during Price's Raid. This raid was part of the American Civil War. In 1864, Sterling Price, a Confederate general, led an attack into Missouri. He hoped to pull Union Army troops away from other important battles. He also wanted to influence the 1864 United States presidential election.

Price's plan started with a failed attack at the Battle of Pilot Knob. Then, the strong Union defenses at Jefferson City made Price change his main goals. Union troops were called back from fighting the Cheyenne. The Kansas State Militia was also called to action. But Kansas leaders would not let their militia fight east of the Big Blue River.

Because of this, Major General James G. Blunt could only take 2,000 men to face Price. By October 19, Blunt's men were near Lexington. Price's army soon attacked them. Blunt's soldiers fought hard, even though they were greatly outnumbered. They forced Price to use his entire army and his biggest cannons. Blunt learned important information about Price's army and where they were. After getting this information, Blunt pulled his troops back. Four days later, Price lost badly at the Battle of Westport. Union forces chased the Confederates, who suffered more defeats. By December, only 3,500 men were left from Price's army, which had started with 13,000.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened: The Background

When the American Civil War began in 1861, Missouri was a state where slavery was allowed. However, it did not leave the United States. The state was divided. Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson and the Missouri State Guard supported the Confederate States of America. But Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon and the Union Army supported the United States.

In 1861, Confederate forces led by Sterling Price won battles at Wilson's Creek and Lexington. But by the end of that year, Price's forces were pushed to the southwest part of Missouri. In March 1862, the Union won the Battle of Pea Ridge in Arkansas. This gave the Union control of Missouri. After this, Confederate actions in Missouri were mostly small attacks and raids.

By September 1864, the war was going badly for the Confederates in the eastern United States. The Union victory in the Atlanta campaign helped Abraham Lincoln in the 1864 United States presidential election. Lincoln wanted to keep fighting the war. At this point, the Confederates had little chance of winning the war.

General Edmund Kirby Smith was a Confederate commander. He was ordered to send his soldiers to fight in the eastern parts of the war. But this was impossible because the Union Navy controlled the Mississippi River. This stopped large groups of soldiers from crossing. Smith decided that an attack to distract Union troops would be just as helpful.

Price and the Confederate Governor of Missouri, Thomas Caute Reynolds, suggested invading Missouri. Smith agreed and put Price in charge. Price hoped his attack would cause people in Missouri to rise up against Union control. He also wanted to pull Union troops away from other battles. Many Union soldiers had already left Missouri, leaving mostly the Missouri State Militia to defend it. Price also hoped his raid would help George B. McClellan defeat Lincoln in the election. On September 19, Price's army, called the Army of Missouri, entered the state.

Getting Ready for Battle

When Price's army entered Missouri, it had about 13,000 cavalry soldiers. But many of these men had poor weapons. All 14 of the army's cannons were not very powerful. The Union forces in Missouri were led by Major General William S. Rosecrans. He had fewer than 10,000 men, and many were militia.

In late September, the Confederates met a small Union force at Fort Davidson near Pilot Knob. Price's attacks on the fort failed in the Battle of Pilot Knob on September 27. The Union soldiers left the fort that night. Price lost hundreds of men in this battle. He then decided to change his target from St. Louis to Jefferson City.

Price's army had a very large wagon train carrying supplies. This made them move very slowly. This delay allowed Union forces to make Jefferson City much stronger. Its defenders grew from 1,000 to 7,000 men between October 1 and October 6. Price then decided Jefferson City was too strong to attack. He began moving west along the Missouri River.

As they moved, the Confederates gathered new soldiers and supplies. A raid on the town of Glasgow on October 15 was successful. Another raid on Sedalia also succeeded.

Meanwhile, Union troops led by Major Generals Samuel R. Curtis and James G. Blunt were called back. They had been fighting the Cheyenne. The Kansas State Militia was also called up. On October 15, Blunt moved two brigades of his troops to Hickman Mills, Missouri. Price was at Marshall, east of Blunt's troops.

The next day, Curtis moved the Kansas militiamen to Kansas City. But the governor of Kansas would not let them go east of the Big Blue River. On October 17, Blunt sent his militia unit to Kansas City. He then sent his other two brigades to Holden.

On October 18, Blunt's lead group, led by Colonel Thomas Moonlight, took over Lexington. They hoped to work with another force to trap Price. But the other force was too far south. Blunt also learned that Price was only 20 miles (32 km) away. He also heard that Kansas would not send more militia. Blunt then decided to strengthen his positions and prepare for Price's attack.

The Battle Itself

Price's army was divided into three groups. Brigadier General Joseph O. Shelby led the front group. Price's total force was still about 13,000 men. Blunt's force had about 2,000 men and two groups of four cannons.

The two armies met 3 miles (4.8 km) south of Lexington around 2:00 PM. Shelby's cavalry met Blunt's scouts first. They pushed the scouts back toward Blunt's main position. Blunt's main force then stood firm against Shelby. This made Price bring in more of his forces. He sent in troops led by Major General James F. Fagan and Brigadier General John S. Marmaduke.

For a while, Blunt's cannons held the line. Price had to use his heaviest cannons. Blunt then pulled his men back from near Lexington. Blunt later explained that he was greatly outnumbered. Also, his smaller cannons could not fight well against Price's bigger ones. The 11th Kansas Cavalry Regiment acted as a rear guard for Blunt until nightfall. Four of the cannons helped protect the Kansans as they retreated.

The Confederates won this battle. But Blunt gained very important information. He learned exactly how strong Price's army was and where it was moving. The Union commanders had not known this before.

What Happened Next

About 40 Union soldiers were killed or wounded. Price did not give an exact number for his losses, but he said they were "very light." The Confederates stayed near Fire Prairie Creek that night. Blunt retreated to the Little Blue River.

Price kept moving west. He fought several smaller battles along the way. But on October 23, Curtis completely defeated him at the Battle of Westport, near Kansas City. The Army of Missouri then retreated through Kansas. They suffered two more defeats on October 25 at the battles of Marais des Cygnes and Mine Creek. The defeat at Mine Creek was very bad, as Marmaduke and many other soldiers were captured.

Price returned to Missouri and was defeated again. This happened at the Battle of Marmiton River on October 25 and at the Second Battle of Newtonia on October 28. Curtis chased the Confederates all the way to the Arkansas River. The Confederates did not stop retreating until they reached Texas. By December, only 3,500 men were left from Price's Army of Missouri.

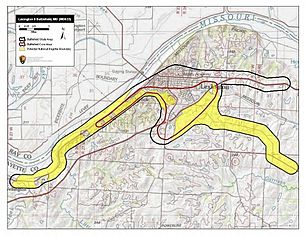

A study in 2011 looked at the battle site. It found that the area is threatened by new roads and buildings. But there are still chances to protect the site. The study also noted that none of the battlefield is on the National Register of Historic Places. However, about 3,543 acres (1,434 ha) of the site might be eligible for listing. The Battle of Lexington State Historic Site focuses on protecting the site of the 1861 First Battle of Lexington.

See also

In Spanish: Segunda batalla de Lexington para niños

In Spanish: Segunda batalla de Lexington para niños

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |