Army of the Tennessee facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Army of the Tennessee |

|

|---|---|

The Siege of Vicksburg

|

|

| Active | 1861–1865 |

| Country | |

| Branch | U.S. Army (Union Army) |

| Type | Field army |

| Part of | District of Cairo (1861–1862) District of West Tennessee (1862) Department of the Tennessee (1862–1863) Military Division of the Mississippi (1863–1865) |

| Nickname(s) | "The Whip-lash" |

| Engagements | American Civil War |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders |

Ulysses S. Grant William Tecumseh Sherman James B. McPherson Oliver O. Howard John A. Logan Joseph Hooker |

The Army of the Tennessee was a very important Union army during the American Civil War. It fought in the Western part of the war. The army was named after the Tennessee River. Many historians say it was at most of the war's major turning points. These included the battles of Fort Donelson, Vicksburg, and Atlanta. This army won many key battles in the most important areas of the war.

The name "Army of the Tennessee" was first used in March 1862. It described the Union forces led by Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. These troops were in the Union's District of West Tennessee. This article also talks about Grant's earlier commands from 1861–1862. These were the District of Southeast Missouri and the District of Cairo. The soldiers Grant led in the Battle of Belmont and the Fort Henry-Fort Donelson campaign became the main part of the Army of the Tennessee.

In April 1862, Grant's troops faced a tough challenge at the bloody Battle of Shiloh. After this, Grant faced some difficult times. His army joined two other Union armies to fight in the Siege of Corinth. Then they worked hard to hold Union positions in Tennessee and Mississippi. In October 1862, Grant's command became the Department of the Tennessee. This made the army's name official. Grant led these forces until his big victory at Vicksburg on July 4, 1863.

After Grant, other generals, like William Tecumseh Sherman, led the army. They marched and fought in many campaigns. These included the Chattanooga Campaign, the Relief of Knoxville, and the Meridian Campaign. They also fought in the Atlanta Campaign, the March to the Sea, and the Carolinas Campaign. The army fought until the war ended and then it was disbanded. In 1867, General Sherman said the Army of the Tennessee was "never checked—always victorious." He said it was "so rapid in motion—so eager to strike." He felt it earned its nickname, "The Whip-lash."

Contents

- The Army's Journey Through the War

- Starting Out: Cairo and Belmont Battle

- Winning Victories: Fort Henry and Fort Donelson

- Tough Fights: Shiloh and Corinth

- Defending the Territory: Iuka and Corinth Battles

- Conquering Vicksburg: A Major Victory

- Moving East: Chattanooga and Knoxville

- Preparing for the March: Meridian Campaign

- The Atlanta Campaign: A Long Battle

- Marching to the Sea: A New Kind of War

- The Final Push: Carolinas Campaign

- The End of the War and Disbandment

- Commanders of the Army of the Tennessee

- See Also

- Images for kids

The Army's Journey Through the War

History remembers the Army of the Tennessee as one of the most important Union armies. It was closely linked to two of the Union's most famous generals, Ulysses S. Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman. It's interesting that military changes and how people used names during the war make it hard to know the exact date the army officially started.

The main group of soldiers that would become the Army of the Tennessee began to form in 1861–1862. This was when Grant was based in Cairo, Illinois. These troops stayed with Grant in his next command, the District of West Tennessee. They were sometimes called the "Army of West Tennessee." However, army letters started using "Army of the Tennessee" in March 1862. This name soon became common. It continued when Grant's command became a larger department in October 1862. This was the Department of the Tennessee.

During the war, parts of the Army of the Tennessee did many different jobs. The army changed as units joined and left. This article will follow the army's main journey and its most memorable actions. At any time, many soldiers were doing other tasks not mentioned here. For example, in April 1863, less than half of Grant's army was directly fighting in the Vicksburg Campaign.

Starting Out: Cairo and Belmont Battle

In September 1861, Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant took command of the District of Southeast Missouri. Grant set up his main base in Cairo, Illinois. One of Grant's helpers, John A. Rawlins, later said that this was when the Army of the Tennessee began to grow.

Just a few days later, Confederate soldiers took over Columbus, Kentucky, on the Mississippi River. Grant quickly led a small force to take Paducah, Kentucky. This town is where the Tennessee River meets the Ohio River. Grant stopped the Confederates from taking this important town.

Grant's first big fight was on November 7 at Belmont, Missouri. This was a landing spot on the Mississippi River across from Columbus, Kentucky. Grant led about 3,000 soldiers to Belmont by boat. They fought their way into the Confederate camps. Then they had to fight their way back to their boats. Grant's army had about 500 casualties in this battle. The Confederates had similar losses. Even though Grant had to retreat, the newspapers wrote good things about him. This battle helped Grant believe he should "give battle" if he had enough men.

Winning Victories: Fort Henry and Fort Donelson

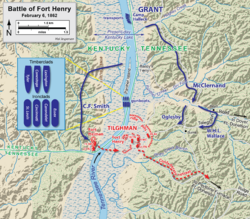

In February 1862, Grant led the Union attack against Fort Henry and Fort Donelson. Fort Henry was on the Tennessee River, and Fort Donelson was on the Cumberland River. His army for this campaign grew to about 27,000 men. They were split into three main groups called divisions.

On February 6, Fort Henry surrendered to the U.S. Navy before Grant's army could even attack. A few days later, in winter weather, most of Grant's army marched overland to attack Fort Donelson. This fort was much stronger. The Battle of Fort Donelson began on February 13. After tough fighting, it ended on February 16. About 15,000 Confederate soldiers surrendered.

These three divisions under Grant became the core of the famous Army of the Tennessee. They had won an important victory. This win was the "first significant Union triumph in the war." It helped secure Kentucky for the Union. It also opened the South, especially Tennessee, to invasion. Grant's soldiers "had performed amazing acts of bravery and endurance." They learned that "hard fighting would bring success." Grant became a national hero for demanding "unconditional surrender."

Tough Fights: Shiloh and Corinth

On February 14, 1862, Grant was given command of the new District of West Tennessee. His troops soon became known as the "Army of the Tennessee." Over the next few months, Grant was almost removed from command twice. This would have greatly changed the army's future.

In early March, Grant's boss, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, ordered Grant to let another general lead an expedition. But Halleck later put Grant back in charge. Grant joined his army on March 17. By early April, Grant's army had grown to about 50,000 men.

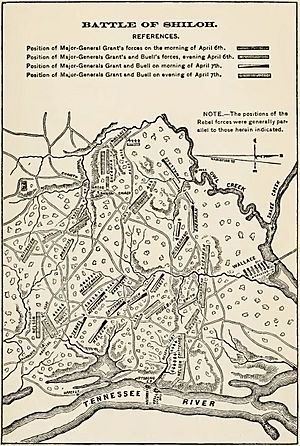

On April 6–7, Grant's forces fought the Battle of Shiloh. This was the bloodiest battle of the Civil War up to that time. Confederate forces surprised and attacked five Union divisions. On the first day, the surprised army fought bravely and lost many soldiers. However, more Union troops arrived to help Grant. These were from the Army of the Ohio and Grant's own 3rd Division. With these new troops, Grant counterattacked on April 7. He pushed the Confederates back. One historian wrote that Grant's victory at Shiloh "doomed the Confederate cause in the Mississippi valley."

After Shiloh, General Halleck arrived to take command in the field. He gathered over 100,000 men to move against Confederate forces at Corinth, Mississippi. This force included Grant's Army of the Tennessee. Halleck made Grant second-in-command of this huge force. But Halleck also gave orders directly to Grant's officers. This made Grant feel like he was being punished.

Halleck's forces took the entire month of May to advance to Corinth. They built trenches as they went. The Siege of Corinth ended when the Confederate forces left the town on May 29–30. William Tecumseh Sherman, who was in Grant's army, thought this campaign was important. He said it helped train the soldiers. He believed the army was "the best then on this continent."

After Corinth was taken, Grant almost left his command. But Sherman convinced him to stay. The trust between Grant and Sherman was very important for the Army of the Tennessee's future success. Halleck soon put Grant back in full command of the "Army of the Tennessee." Grant's army was spread out across the Mississippi-Tennessee border. Grant had survived challenges to his leadership. He was now able to shape the Army of the Tennessee to be like him: steady and aggressive.

Defending the Territory: Iuka and Corinth Battles

In July 1862, President Lincoln called Henry Halleck to Washington. Halleck became the general-in-chief of all Union armies. This meant Grant's command became even bigger. Grant moved his headquarters to Corinth.

Grant soon lost many soldiers to another Union army. This made Grant's forces shrink to less than 50,000 men. Grant felt he was on the "defensive." He later said this was his "most anxious period of the war." This difficult time ended with victories led by General William S. Rosecrans. These were the Battle of Iuka in September and the more important Battle of Corinth in October. Grant was nearby and helped plan, but he wasn't on the battlefield for these fights. The victory at Corinth made Grant feel much better about the safety of his area.

Soon after, on October 16, Grant's command became the Department of the Tennessee. This made the name "Army of the Tennessee" official for his troops. Grant's Army of the Tennessee was organized into four main groups called corps. These were led by generals like John McClernand, William T. Sherman, Stephen A. Hurlbut, and James B. McPherson.

Conquering Vicksburg: A Major Victory

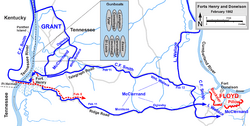

In late 1862, Grant began planning to capture Vicksburg, Mississippi. This was a strong Confederate fort on the Mississippi River. Grant's first attempt failed in December. Confederate attacks on his supply lines forced him to stop. Sherman also faced a setback in the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou.

Meanwhile, Grant's general, John McClernand, used his political connections to get permission for his own attack on Vicksburg. This was a strange event in the war. But it helped the Army of the Tennessee in the long run. McClernand raised new troops in the Midwest. In January 1863, McClernand took control of Sherman's 30,000 men. This force captured Fort Hindman. Grant thought this was a waste of time. General Halleck then let Grant take control of all Vicksburg operations. So, McClernand's force joined the Army of the Tennessee again.

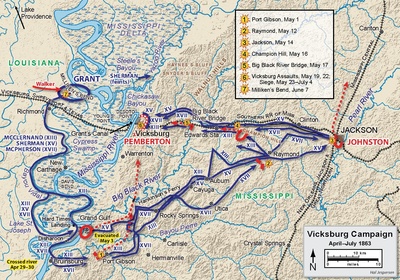

In early 1863, Grant tried different ways to capture Vicksburg from the north. These attempts didn't work. But in April, Grant marched his troops down the west side of the Mississippi River. He crossed the river with help from the Navy. Grant worked well with the Western Flotilla led by Admiral David D. Porter. Grant led about 40,000 men in a brilliant campaign. He moved his army 180 miles (288 km) against two Confederate armies.

After capturing Jackson, Mississippi, on May 14, and winning the Battle of Champion Hill on May 16, Grant attacked Vicksburg directly. His attacks on May 19 and 22 failed. So, he began a siege instead of losing more soldiers.

During the siege, the army received many more soldiers. Grant's total strength at Vicksburg grew to over 70,000 soldiers. On June 18, Grant replaced McClernand as commander of the XIII Corps. The city finally surrendered on July 4. Its 30,000 soldiers were allowed to go home instead of being taken prisoner.

Grant's capture of Vicksburg was one of the most important Union victories of the war. It opened the Mississippi River for the Union. It also cut the Confederacy in half. Grant was promoted to major general in the regular army. Sherman later wrote that with Vicksburg's capture, "Grant's army had seemingly completed its share of the work of war." Even though more work lay ahead, Sherman's words had truth. Grant would soon move to bigger roles. The Army of the Tennessee would move its operations eastward. It would begin a series of epic marches. After Vicksburg, the Army of the Tennessee often worked with other forces, especially the Army of the Cumberland.

Moving East: Chattanooga and Knoxville

After taking Vicksburg, the Army of the Tennessee rested for a while. But soon, the army and its leaders took on new roles. In November 1863, a mixed Union force won a victory in the Battles for Chattanooga.

In late September 1863, Confederate General Braxton Bragg's Army of Tennessee defeated William Rosecrans's Army of the Cumberland. Rosecrans retreated to Chattanooga, Tennessee, and Bragg surrounded him. To fix this problem, Washington promoted Grant to command of the new Military Division of the Mississippi. Grant was ordered to go to Chattanooga, take command, and defeat Bragg. Grant chose George Thomas to lead the Army of the Cumberland. Grant's forces at Chattanooga included soldiers from three armies. These were the Army of the Cumberland, troops from the Army of the Potomac, and 17,000 men from the Army of the Tennessee.

William Tecumseh Sherman led the Army of the Tennessee's group to Chattanooga. He marched them up the Mississippi River from Vicksburg and then east from Memphis. Sherman started as a corps commander. He ended up replacing Grant as commander of "the Department and Army of the Tennessee."

With Sherman's force, Grant was ready to attack and break Bragg's siege. Grant ordered Sherman to attack the right side of Bragg's army. This attack was supposed to be the main Union effort. However, in the Battle of Missionary Ridge on November 25, Sherman's attack didn't gain much ground. It was up to Thomas's Army of the Cumberland to break the Confederate line. They attacked directly up the middle of Missionary Ridge. So, in this battle, the Army of the Tennessee played a supporting role.

Right after Chattanooga, Grant ordered Sherman to lead a force to break another siege. Other Confederate forces had surrounded Ambrose Burnside's command at Knoxville, Tennessee. Sherman's approach alone caused the siege to be lifted. Sherman later calculated that his troops had marched 330 miles (531 km) from Memphis to Chattanooga. Then they marched 230 miles (370 km) from Chattanooga to Knoxville and back.

Preparing for the March: Meridian Campaign

Only about a third of Sherman's Army of the Tennessee had fought in the Chattanooga and Knoxville campaigns. Most of the other corps had stayed on other duties. In early 1864, Sherman organized an expedition of 20,000 men. They moved into central Mississippi. Their goal was to destroy Confederate rail lines and other important things. This would help the Union control the Mississippi River.

This force, led by Sherman himself, marched about 330 miles (531 km) from Vicksburg to Meridian, Mississippi, and back. They faced little resistance. This force destroyed the transportation center at Meridian in mid-February. One study called this campaign a "dress rehearsal" for Sherman's later style of war. He would destroy infrastructure in Georgia during the March to the Sea. Another historian said the Meridian campaign taught Sherman that he "could march an army through Confederate territory safely." He learned he could feed his army using the land. He could fight a successful war without losing thousands of soldiers.

The Atlanta Campaign: A Long Battle

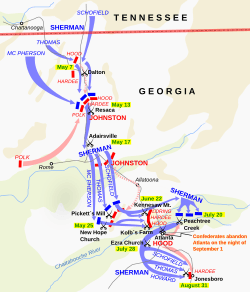

Now that Chattanooga was safe, the way was open to invade the heart of the Deep South. Sherman was chosen to lead this invasion in the 1864 Atlanta Campaign. The Army of the Tennessee was his "whiplash." In March 1864, Lincoln promoted Ulysses S. Grant to Lieutenant general. Grant was given command of all Union armies. He moved to the Eastern part of the war. Sherman took Grant's place in command of the Military Division of the Mississippi.

Command of the Army of the Tennessee then went to Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson. On the Confederate side, General Joseph E. Johnston replaced Braxton Bragg. Later, Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood replaced Johnston.

Sherman later said the Atlanta campaign, which started in early May, was "a continuous battle of 120 days." It was fought for "over a hundred miles [160 km]" along the railroad. "Day and night, were heard the continuous boom of cannon and the sharp crack of the rifle." For this campaign, the Army of the Tennessee started with about 25,000 men. Sherman's total force was about 100,000 men. It also included George Thomas's larger Army of the Cumberland and Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield's smaller Army of the Ohio. Sherman often used the Army of the Tennessee for flanking moves.

As Sherman moved south, Johnston was dug in at Dalton, Georgia. Sherman tried to get behind Johnston at Resaca. He sent McPherson to the west through Snake Creek Gap. McPherson reached Johnston's rear. But he took a defensive position instead of cutting Johnston's railroad link. After the rest of Sherman's forces moved up, the first big battle of the campaign happened at Resaca (May 13–15). Johnston had to fall back toward Adairsville.

This set the pattern for the first part of the campaign. Sherman's armies tried to move around Johnston. Johnston kept falling back toward Atlanta. On June 27, Sherman tried a direct attack on Johnston's position at Kennesaw Mountain. When that failed, Sherman moved McPherson's army to the right to continue moving south. On July 18, John Bell Hood replaced Johnston as the Confederate commander.

The aggressive Hood soon started the Battle of Peachtree Creek (July 20). His attack failed. Then, in the Battle of Atlanta on July 22, Hood launched a strong attack against McPherson's army. McPherson himself was killed. Command temporarily went to Maj. Gen. John A. Logan. The July 22 battle was "the climax of the Army of the Tennessee's wartime career." About 27,000 men "defeated the attacks of nearly 40,000 Confederates."

Even though Logan won the battle that day, Sherman chose Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard to lead the Army of the Tennessee. Sherman then moved the Army of the Tennessee to his right flank, west of Atlanta. This led to the Battle of Ezra Church on July 28. Howard easily stopped Hood's third attack in nine days. Sherman finally broke the stalemate in late August. He moved the Army of the Tennessee south of Atlanta to attack Hood's last rail lines. On August 31, Howard's army stopped a final Confederate attack in the first day of the Battle of Jonesborough. Hood then left Atlanta during the night of September 1–2. Sherman's capture of Atlanta was a huge victory. It helped President Lincoln get reelected in November.

Marching to the Sea: A New Kind of War

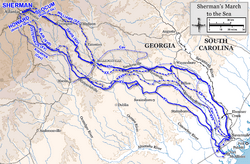

The Army of the Tennessee, under Oliver O. Howard, would now be Sherman's right arm in the March to the Sea and the Carolinas Campaign. After losing Atlanta in early September, Confederate General Hood tried to draw Sherman back north. Sherman estimated that his own movement back and forth involved 270 miles (435 km) of marching by the Army of the Tennessee.

Sherman got approval to send other forces to defend Tennessee. He then cut off his supply lines back to Chattanooga. He marched southeast to the sea with about 60,000 men. In November and December, the Army of the Tennessee was the right wing during the 280-mile (451 km) march to the sea. Howard's command included the XV Corps and the XVII Corps. Sherman's other column was the Army of Georgia.

Sherman said his march to the sea was mostly unopposed. His troops lived off the land. They also hurt the South's morale by destroying a lot of property. In the final part of the march, Sherman's troops captured Fort McAllister. On December 21, the march ended with the capture of Savannah, Georgia. Sherman presented Savannah to Lincoln as a "Christmas-gift." This march showed that the Confederacy's "days were numbered." It also hurt the morale of the Confederate army in Virginia.

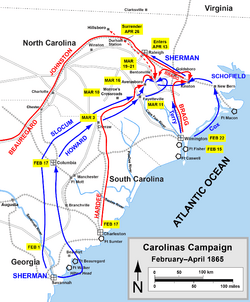

The Final Push: Carolinas Campaign

On February 1, 1865, Sherman continued his destructive march northward into the Carolinas. His goal was to meet up with Grant's forces in Virginia. Howard's Army of the Tennessee was again the right wing of the advance. Resistance was light in South Carolina. Sherman's troops caused much destruction there.

Confederate opposition grew stronger in North Carolina. It was led by Sherman's old enemy, Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston. At Sherman's last big battle, Bentonville in mid-March, most of the fighting was done by other Union forces. Johnston then slipped away. Sherman met up near Goldsboro with forces Grant had sent from Tennessee. The Army of the Tennessee had marched about 450 miles (724 km) in 50 days from Savannah to Goldsboro. It seemed nothing could stop Sherman from joining Grant in Virginia. Sherman later wrote that this was "one of the longest and most important marches ever made by an organized army."

The End of the War and Disbandment

On April 10, 1865, the day after Robert E. Lee surrendered to Grant, Sherman continued his advance. He headed toward Raleigh, North Carolina. He now had almost 90,000 soldiers. Sherman learned of Lee's surrender on the night of April 11–12. His immediate target was General Johnston's Confederate force near Raleigh. But there was little need for more fighting.

Sherman entered Raleigh on April 13. Johnston soon began surrender talks. On April 26, Johnston finally surrendered all Confederate forces in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida to Sherman. The Army of the Tennessee then marched about 250 miles (402 km) to Washington, D.C.. On May 24, they took part in the Grand Review there with Sherman.

To make up for not choosing John A. Logan to lead the army after McPherson's death, Sherman arranged for Logan to be the final commander of the Army of the Tennessee. So, while Howard rode with Sherman, Logan led the army in the Grand Review. On July 13, Logan gave a farewell speech to the Army of the Tennessee. He spoke of their four years of fighting. He said they had carried the flag until it flew "from the Lakes to the Gulf, and from ocean to ocean." The Army of the Tennessee was officially disbanded on August 1, 1865.

Commanders of the Army of the Tennessee

The Army of the Tennessee had several important commanders throughout its history:

- Ulysses S. Grant: Led the army from its early days in 1861 through the major victory at Vicksburg in July 1863.

- William Tecumseh Sherman: Took command in October 1863 and led the army through the Chattanooga, Meridian, and early Atlanta campaigns.

- James B. McPherson: Assumed command in March 1864 for the Atlanta Campaign, where he was tragically killed in July 1864.

- John A. Logan: Briefly commanded the army after McPherson's death during the Battle of Atlanta in July 1864. He also became the final commander of the army in May 1865.

- Oliver O. Howard: Took over from Logan in July 1864 and led the army through the rest of the Atlanta Campaign, the March to the Sea, and the Carolinas Campaign.

See Also

Images for kids

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |