Camp Nelson Heritage National Monument facts for kids

|

Camp Nelson Heritage National Monument

|

|

Camp Nelson in 2008

|

|

| Location | Jessamine County, Kentucky, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Nicholasville, Kentucky |

| Architect | U.S. Army of the Ohio Eng. Corps; Simpson, Lt.Col. J.H. |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival |

| Website | Camp Nelson Heritage National Monument |

| NRHP reference No. | 00000861 (NRHP), 13000286 (NHL) |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | March 15, 2001 |

| Designated NHLD | February 27, 2013 |

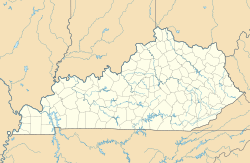

Camp Nelson Heritage National Monument is a special place in Jessamine County, Kentucky. It covers about 525 acres. This site is a national monument, a history museum, and a park. It is located about 20 miles south of Lexington, Kentucky.

During the American Civil War, Camp Nelson was a key base for the Union Army. It was set up in 1863. The camp served as a supply center for soldiers. It also became a major place for recruiting new soldiers. Many of these new soldiers were formerly enslaved people. They had bravely escaped their difficult lives to join the army.

On October 26, 2018, President Donald Trump made the site a national monument. It became the 418th unit of the National Park Service (NPS). In 2019, its name was changed to include "Heritage." This change was part of a new law. A beautiful forested part of the camp, overlooking Hickman Creek, was saved with help from the Kentucky Heritage Land Conservation Fund.

Contents

History of Camp Nelson

Early Years of the Camp

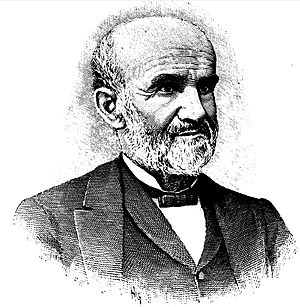

Camp Nelson was created in 1863. It was a supply base for Union troops moving into Tennessee. The camp was named after Major General William "Bull" Nelson. He had recently passed away. The camp was placed near Hickman Bridge. This was the only bridge over the Kentucky River upriver from the state capital.

The location was chosen for several reasons. It helped protect the bridge. It also gave the Union Army a central base in Kentucky. From here, they could prepare to secure the Cumberland Gap and eastern Tennessee. The camp also trained many new Union soldiers. The steep cliffs of the Kentucky River and Hickman Creek made the site easy to defend. Only the northern side needed strong forts against Confederate attacks. The other three sides had very steep cliffs.

Even with its good location, Camp Nelson had some challenges. It was far from the Cumberland Gap and Knoxville, Tennessee. There were also no railroads nearby. Bad weather made it even harder to move supplies. These issues slowed down the Union advance.

Despite these problems, General William Tecumseh Sherman saw a new role for Camp Nelson. He wanted it to train 10,000 black soldiers. These brave men volunteered for the U.S. Colored Troops. General Ulysses S. Grant visited Camp Nelson in 1864. He had doubts about the camp's supply routes. But Camp Nelson continued to be important. It supplied major battles in 1864. These included the battles of Saltville and Atlanta. The camp even provided 10,000 horses for the Atlanta campaign.

Union forces knew that Camp Nelson and Hickman Bridge were important targets. Confederate raider General John Hunt Morgan tried to attack them in 1863 and 1864. The biggest threat was in June 1864. Brig. General Speed S. Fry asked civilian workers to help. Six hundred volunteers were given weapons. They guarded the northern forts day and night for six days. Their efforts saved the camp from being captured.

Black History: Soldiers, Workers, and Freedom

Kentucky was a slaveholding state. But it did not join the 11 other southern states that formed the Confederate States of America. The Civil War was largely about slavery. Black people in Kentucky, both enslaved and free, helped the Union war effort greatly. They first worked as laborers. Later, they became soldiers in the infantry, artillery, and cavalry.

Because Kentucky was not in rebellion, enslaved people escaping there were not considered "contrabands." The Confiscation Act of 1861 applied only to the Confederacy. This law said the military could use enslaved people as workers. However, the Union Army in Kentucky still started using thousands of enslaved people for labor. They first used those who had escaped or whose owners were disloyal. Enslaved people whose owners were unknown or disloyal received wages. Loyal slaveholders were paid for their enslaved workers' labor.

In August 1863, Brig. General Jeremiah Boyle allowed Commander Speed S. Fry to impress enslaved men. These men were aged 16–45 from 14 counties in Central Kentucky. Up to one-third of an enslaver's workforce could be taken. The military hired agents to get enslaved men to work at Camp Nelson. For example, Gabriel Burdett was impressed from a nearby farm. Slave owners received $30 per month for each impressed worker. By 1864, some, like Gabriel Burdett, joined the U.S. Colored Troops.

About 3,000 impressed workers were at Camp Nelson in 1863. They did hard but important work. They helped build railroads and the northern forts. They also built 300 buildings. This work was vital for the camp's creation and defense.

President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, freed enslaved people only in the rebellious Confederate states. Kentucky was a slaveholding state but not in rebellion. So, the proclamation did not apply there.

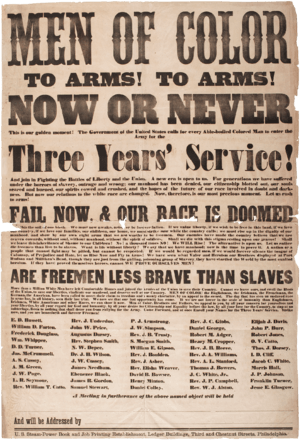

However, African Americans who joined the Union Army were freed from slavery. Kentucky recruited and trained over 23,000 U.S. Colored Troops (USCT). This made it the second-largest contributor of any state. Camp Nelson was the biggest site in Kentucky. More than 10,000 recruits joined there. Eight USCT regiments were formed at Camp Nelson. Five others were stationed there during the war.

Lincoln wanted more black Kentuckians to join the Union Army. In 1863, a special count showed 1,650 free black men and 40,000 enslaved men of military age. White men were not meeting the state's draft goals. So, Governor Thomas E. Bramlette agreed in March 1864 that black men could join the US Army. Their owners had to give consent and received $300.

By April, enslaved men began escaping to enlist, even without owner consent. The military often sent men back to their owners if consent was unclear. This led to violence. The military allowed groups hired to catch runaways into Camp Nelson. Captain Theron E. Hall reported that the camp became a "hunting ground for fugitives."

Because of this violence, owner consent was no longer needed by June 1864. This was ordered by Union Army Adj. Gen. Lorenzo Thomas.

The largest groups of African-American recruits arrived between June and October 1864. On July 25, 322 men enlisted in one day. In May 1864, 250 recruits came from Danville, 16 miles away. These groups often faced harassment and violence on their way to Camp Nelson. Thomas Butler reported that the Danville group was "assailed with stones and the content of revolvers."

Peter Bruner tried to enlist but was captured. He was jailed in Nicholasville with 24 others trying to join the USCT. Rev. John Gregg Fee noted that "three of five recruits bore on their bodies marks of cruelty." Despite this, army doctors found most recruits to be healthy and fit.

Families of soldiers and others escaping slavery came to Union camps like Camp Nelson. They were called refugees. Unlike the soldiers, refugees were not initially freed. The army did not have a clear plan for them. But they were allowed to build a shanty village at Camp Nelson.

However, from November 22–25, 1864, District Commander Speed S. Fry changed this. Under pressure from slave-owners, he ordered soldiers to force out 400 women and children. They were put on wagons and escorted out. Fry also ordered the refugee huts to be burned. Temperatures were below freezing. As a result, 102 refugees died from cold and disease.

Camp Nelson Chief Quartermaster Theron E. Hall and Reverend John Gregg Fee spoke out. They told newspapers and officials in Washington. Hall collected stories from USCT soldiers about their families' suffering. He sent them to Brig. General Stephen G. Burbridge. Burbridge ordered Fry to stop the expulsions. He told him to let the families return and provide housing. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton also ordered that permanent shelter be built for all refugees. This included those not related to USCT troops.

The New York Tribune published a front-page story on November 28, 1864. It was titled "Cruel Treatment of the Wives and Children of U.S. Colored Soldiers." It described how over 400 people were "driven from their homes by United States soldiers." They were "lying in barns and mule sheds, wandering through the woods... literally starving." Their only "crime" was that their husbands and fathers had joined the Union Army.

By December 1864, the military changed its policies. They approved building the Home for Colored Refugees. This included duplex cottages for families. There was also a mess hall, barracks, a school, and a dormitory.

These events led to a new law on March 3, 1865. This law freed the wives and children of the U.S. Colored Troops. This was a big step against slavery. The Home's population grew to 3,060 by July 1865. It became too crowded. So, 60 large army tents were added. Refugees also built their own makeshift homes again. A monument at the refugee cemetery honors about 300 refugees who died at Camp Nelson. Some died because of the November 1864 expulsion.

The two-story school was staffed by the American Missionary Association. Two African Americans, E. Belle Mitchell and Reverend Gabriel Burdett, were teachers. Mitchell's stay was short due to staff prejudices. Burdett was also a USCT soldier. He helped Fee with ministry work.

Two barracks became the refugee hospital. Infectious diseases were common. About 1300 refugees died at Camp Nelson.

Units formed at Camp Nelson include the 5th and 6th U.S. Colored Cavalry (USCC). Also, the 114th, 116th, 119th, and 124th Colored Infantry. And the 13th and 12th United States Colored Heavy Artillery.

Brave Actions of Camp Nelson Colored Troops

The 5th and 6th USCC fought in important battles. These included the Battle of Saltville I and the Battle of Saltville II in Virginia. Brig. General Stephen G. Burbridge led the first Saltville battle in October 1864. The goal was to destroy Confederate saltworks. These had been fortified by impressed enslaved workers.

Saltville I was a defeat for the Union. But Colonel James Sanks Brisbin praised the bravery of the 400 USCT soldiers. He said he had never seen white troops fight more courageously. Ten colored troops were killed, and 37 were wounded. After the battle, violence broke out. Forty-seven soldiers from the 5th and 6th USCC were killed unfairly. Champ Ferguson led these attacks. He was later tried for war crimes and executed.

In December 1864, the 5th and 6th USCC fought in the successful second assault on Saltville. These units included survivors from the first battle. Union Generals George Stoneman and Burbridge fought General John C. Breckinridge. Union troops outnumbered them. Breckinridge retreated. Union troops destroyed the saltworks. They also damaged nearby lead mines and railroads. The USCC troops earned a strong reputation for their bravery.

In January 1865, the 5th USCC faced another violent attack in Simpsonville, Kentucky. Eighty soldiers were moving 1,000 cattle from Camp Nelson to Louisville. Confederate guerrillas attacked them. Many soldiers could not fire their guns. Locals found 15 dead and 20 wounded. The attackers boasted about killing 19 Union soldiers. Lt. Colonel Louis H. Carpenter recorded the names of the attackers. He urged that they be punished, but this never happened. In 2009, a memorial was placed at the ambush site.

The 6th USCC and the 114th and 116th Colored Infantry were active in General Grant's Appomattox campaign. This was from March to April 1864. These units helped in the siege of Petersburg, Virginia, and Richmond, the Confederate capital. These soldiers chased Confederate General Robert E. Lee to the Appomattox Courthouse. There, they saw the Confederate Army surrender.

White Refugees and Union Troops from East Tennessee

Tennessee was a Confederate state. But many people in eastern Tennessee were loyal to the Union. This area had fewer enslaved people compared to western Tennessee.

Thousands of poor people from this area came to Camp Nelson for help. Thomas D. Butler, who cared for them, described one family. Rebels had driven a mother and her six children from their home. They destroyed their property. For many weeks, they "wandered, homeless, hungry and sick" to reach Camp Nelson. The husband was a Union soldier who had been captured. He escaped and reunited with his family at the camp.

Several East Tennessee regiments were trained at Camp Nelson.

- The 8th Tennessee Volunteer Infantry was commanded by Felix A. Reeve. It was formed at Camp Nelson from 1862 to 1863. It fought in the Knoxville campaign in late 1863.

- Five companies of the 5th East Tennessee Cavalry (also called the 8th Tennessee Cavalry) were formed from June to August 1863.

- The 10th, 12th, 13th Cavalry and Battery E of First Tennessee Light Artillery also trained here.

After the War

After the war, Camp Nelson helped former enslaved people get their freedom papers. Many saw the camp as their "cradle of freedom." The United States Sanitary Commission (USSC) ran a soldiers' home there for a while. It was in former barracks.

Here are some achievements of Camp Nelson U.S. Colored Troops after the war:

Angus Burleigh was able to read and write. He enlisted at age 16. He became a sergeant with the 12th Regiment Heavy Artillery U.S. Colored Troops. He had escaped from a farm. In 1875, he was the first black graduate of Berea College. He was also the first black adult male to enroll. The college was founded by John Fee in 1855. It enrolled both black and white students. Burleigh taught in schools for freed people. He later became a Methodist minister. He served as a chaplain to the Illinois State Senate. He lived until 1914.

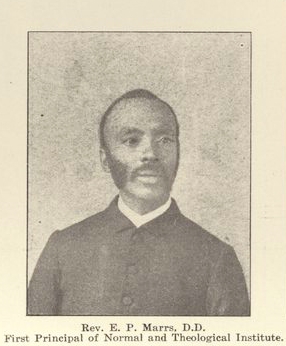

Elijah P. Marrs led 27 others to join the USCT. Marrs was another sergeant with the 12th US Colored Heavy Artillery. He trained at Camp Nelson and taught reading there. After the war, Marrs taught school. He also became a Baptist minister. In 1879, he and his brother founded a college in Louisville. It later became Simmons Bible College. Marrs was active in the Republican party in Kentucky. You can read his autobiography online.

Peter Bruner wrote his autobiography with his daughter. It is called A Slave’s Adventure Toward Freedom. He described his many escape attempts and the harsh punishments he received. He was also a member of the 12th USCT. He enlisted with 16 other men. They walked 41 miles from Irvine, Kentucky. After the war, Bruner moved to Oxford, Ohio. He became the first African American to work at Miami University. He also enrolled there. He worked as a custodian and messenger. He also served as a ceremonial greeter, wearing a top hat and tails. He raised five children with his wife. He is honored at the African American Civil War Memorial in Washington D.C. His ceremonial top hat is on display at a museum at Miami University.

Gabriel Burdett was enslaved in Garrard County. He became active in ministry. He enlisted in July 1864 in the 114th U.S. Colored Infantry. He served as a teacher, nurse, and minister. He helped develop education, housing, and aid for the refugees. He worked with John Fee and the American Missionary Association for 12 years. After serving in Tennessee and Texas, Burdett returned. He helped establish Ariel Academy. He became the first African American on the Berea College Board of Trustees. He served for 12 years. He was involved in the Republican Party. He campaigned for President Grant's reelection in 1872. He was a voting member at the 1872 Republican National Convention and 1876 Republican National Conventions. The violence around the 1876 election led Burdett to join the Exodusters Movement. He moved with his family to Kansas.

Camp Nelson Today

Today, 525 acres of the original Camp Nelson property are preserved. It is now the Camp Nelson Heritage National Monument. Most of the original buildings were sold after the war. The camp is listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). It was also named a National Historic Landmark District in 2013. The site is part of the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom. This network connects sites across several states and even in Canada.

Camp Nelson is in a more rural area than other former USCT recruitment sites. It is the only one whose land was never developed for other purposes after the war.

Before becoming a national monument, Camp Nelson was a Civil War Heritage Park. It was managed by Jessamine County. The forested area overlooking Hickman Creek was funded by the Kentucky Heritage Land Conservation Fund. In 2017, U.S. Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke suggested making it a national monument. In 2018, President Trump used the Antiquities Act to create Camp Nelson National Monument. This transferred its ownership to the National Park Service. In 2019, legislation officially renamed it "Camp Nelson Heritage National Monument."

The Oliver Perry House is the only original building left from the camp years. It was built around 1846. General Ambrose Burnside used it as officers' quarters during the war. It was often called the "White House" in official letters. Today, it is a historic house museum at the park.

The park has five miles of walking trails. They are open from dawn to dusk. Along the northern border, you can see remains of the forts. Historic signs mark these spots. Fort Putnam has been rebuilt to look like the original. Re-enactors sometimes fire a Napoléon 12-pound cannon there. This happens during the Annual Civil War Heritage Weekend in September. On April 15, the date of President Lincoln's death, a ceremonial firing takes place at Fort Putnam. The interpretive center is open Tuesday through Saturday. Tours are also available.

Camp Nelson National Cemetery is one mile south. It has online records of burials. Families can use these to find relatives buried there. They can also find those who trained or lived at the camp.

Gallery

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |