Quashquame facts for kids

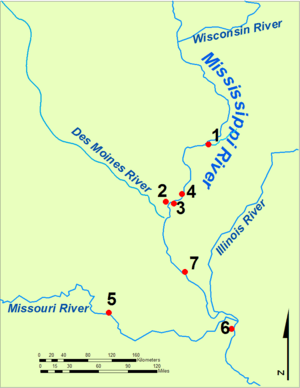

Quashquame (meaning "Jumping Fish") was an important Sauk chief. He lived from about 1764 to 1832. He is best known for signing a treaty in 1804. This treaty gave Sauk land to the United States government. Quashquame also led two large villages of Sauk and Meskwaki people. These villages were near modern-day Nauvoo, Illinois and Montrose, Iowa. He also had a camp in Cooper County, Missouri.

Contents

The Disputed Treaty of 1804

Quashquame is most famous for leading a group to St. Louis in 1804. They signed a treaty that gave away land in western Illinois and northeast Missouri. William Henry Harrison oversaw this treaty. However, the Sauk people said the group was not allowed to sign land treaties. They also said the delegates did not understand what they were signing.

Black Hawk, another Sauk leader, wrote about this treaty in his book. He said the Sauk and Meskwaki group went to St. Louis for a different reason. They wanted to get a murder suspect released. They also wanted to make up for a killing. They were not sent to sell land. This treaty made many Sauk people unhappy with the U.S. government. It also led many, including Black Hawk, to support the British in the War of 1812.

One of our people killed an American. He was taken prisoner in St. Louis. We held a meeting to see what we could do for him. We decided that Quashquame, Pashepaho, Ouchequaka, and Hashequarhiqua should go to St. Louis. They would meet our American father. They would try to get our friend released. They would pay for the person killed. This was our way of saving someone who had killed another. We thought the white people did the same.

The group left with the good wishes of our whole nation. We hoped they would succeed. The prisoner's family fasted. They hoped the Great Spirit would help them. They wanted their husband and father to return home.

Quashquame and his group were gone a long time. They finally returned. They camped near the village. They did not come into the village that day. No one went to their camp. They seemed to be wearing nice coats and medals. We hoped this meant they had good news. Early the next morning, the Council Lodge was full. Quashquame and his group came in. They told us about their trip:

"When we arrived in St. Louis, we met our American father. We told him why we were there. We asked for our friend to be released. The American chief told us he wanted land. We agreed to give him some on the west side of the Mississippi. We also agreed to give more on the Illinois side. When everything was settled, we expected our friend to be released. He would come home with us. Just as we were ready to leave, our brother was let out of prison. He started to run a short distance. Then he was SHOT DEAD!"

<…>

This was all my nation and I knew about the 1804 treaty. It has since been explained to me. I found that by that treaty, all the land east of the Mississippi was given to the United States. This was for one thousand dollars a year. I will let the people of the United States decide. Was our nation properly represented in this treaty? Did we get fair payment for all the land these four people gave away?

I could say much more about this treaty. But I will not now. It has caused all our serious problems with the whites. [...] After I asked Quashquame about selling our lands, he told me he "never agreed to sell our village."—-Black Hawk (1833) Autobiography (1882 edition)

Staying Neutral During the War of 1812

In 1806, people heard that Quashquame was leading a large group. It included 500 Sauk, Meskwaki, and Ioway people. They were near the Missouri River, west of St. Louis. This village might have been at Moniteau Creek. Quashquame later had a temporary village there.

By 1809, Quashquame was back near the Mississippi River. He attended meetings with the U.S. Army at Fort Madison. This was a difficult time before the War of 1812. Quashquame and his group of Sauk stayed neutral during the war. This means they did not pick a side.

In 1809, some Sauk, possibly led by Black Hawk, tried to attack Fort Madison. The soldiers stopped them by threatening to fire cannons. The next day, Quashquame and two other Sauk leaders tried to fix things. They told the commander, Alpha Kingsley, that the attackers acted alone. They said those people had left the area. Kingsley showed the Army's power. He fired a cannon. The Sauk were amazed. They said that shot "would have killed half of them."

Quashquame tried to calm General William Clark during a meeting around 1810 or 1811. He told Clark, "My father, I came to see the president of the United States. But I cannot go to him. So I give you my hand as if you were him. You are the only father I have listened to. If you hear anything, please let me know. I will do the same. I have been told many times to fight. Since the last war, we have seen Americans as friends. I will hold your hand tightly. The Great Spirit did not put us on earth to fight white people. We have never attacked a white man. If we go to war, it is with other Native American groups. Other nations send messages to us. They urge us to fight. They say if we do not, Americans will take our land." Around 1810, Quashquame had a camp along Moniteau Creek. This was in southern Cooper County, Missouri, perhaps near Rocheport.

Quashquame was in charge of the Sauk who were not warriors during the War of 1812. Black Hawk wrote: "... all the children and old men and women belonging to the warriors who had joined the British were left with them to provide for. A council had been called which agreed that Quashquame, the Lance, and other chiefs, with the old men, women and children, and such others as chose to accompany them, should descend the Mississippi to St. Louis, and place themselves under the American chief stationed there. They accordingly went down to St. Louis, were received as the friendly band of our nation, were sent up the Missouri and provided for, while their friends were assisting the British!"

More Treaties and Agreements

Quashquame represented the Sauk in several treaties after the war. In 1815, he was part of a group that signed a treaty. This treaty confirmed a split between the Sauk along the Missouri River and those along the Rock River. The Rock River Sauk were known as the British Band. They were a main group of Native Americans who fought in the Black Hawk War. In 1825, Quashquame also signed the First Treaty of Prairie du Chien. This treaty set up boundaries between different tribes.

Quashquame's Villages

Quashquame had a village near what is now Nauvoo, Illinois. Later, it joined an older village on the west side of the Mississippi. This was near Montrose, Iowa. While living at the eastern village, Quashquame helped settle a problem. A white trader had murdered a Sauk person near Bear Creek in 1818. Around 1824, Captain James White bought the eastern village from Quashquame.

Quashquame's village then moved to the west bank of the river. It merged with an existing Sauk village near Montrose, Iowa. This western village was also called Cut Nose's Village or Wapello's Village. It was at the top of the Des Moines Rapids. This was an important place for trade on the Mississippi. Records show this village was used from the 1780s until the 1840s. Zebulon Pike visited this village in 1805. Caleb Atwater visited it in 1829.

A Visitor's Story: The 1829 Interview

Caleb Atwater visited Quashquame in 1829. Atwater's visit gave the most detailed description of Quashquame. It also described his village near Montrose. Atwater found that Quashquame was a skilled artist.

With Mr. Johnson, a former Indian trader, I visited Quasquawma's village of Fox Indians. This town was across from our island. It was on the west bank of the river. It had about forty or fifty people. We landed our canoe. We went to Quasquawma's wigwam. We found him and several of his wives and children at home. These Indians had joined the United States during the late war. The wigwam we visited was a good example of all we saw later. It was covered with white elm bark. The bark was fastened to upright posts in the ground. Ropes made of bark passed through the covering. They were tied inside around the posts.

I think this dwelling was forty feet long and twenty wide. Six feet on each side, inside the doors, was where the family slept. Their beds were platforms. They were raised four feet high from the earth. They rested on poles. These poles were tied to upright posts. On these poles, they laid tree barks. On these barks, they laid blankets and animal skins. These were the beds. Between these beds was an open space. It was perhaps six or eight feet wide. It ran the whole length of the wigwam. In this space, fires were lit in cold and wet weather. Here, they cooked. The family warmed themselves and ate their food. There was no chimney. The smoke either went through the roof or out the doors. On all the waters of the Upper Mississippi, no better dwelling is found among the Indians. Quasquawma was resting on his bed when we entered his home. The only person working was one of his wives at the door. She was preparing a deer skin. He seems to be about 65 years old, perhaps even older.

He seemed very friendly to Mr. Johnson, whom he knew well. We had a long and interesting talk with him. We told him all our business. We asked for his advice and help. He gladly promised. He was very helpful to us from then on. This was until the treaties were finished. His son-in-law, a main chief of the Foxes, was not home then. We did not see him until we reached Rock Island.

Quasquawma showed us where he had carved a picture of a steamboat on bark. It had everything belonging to it. This bark was part of his dwelling. It was carved on the inside. It seems he tried three times before he got it right. He finally succeeded perfectly. The cannon was firing. A dog was sitting near an army officer. The officer had his hat on. His shoulder decorations were on his shoulders. Several soldiers were standing on the boat. Nothing could be more real than this picture. He was clearly very proud of it. We praised it greatly, which pleased him. A few small patches of corn were growing nearby. But they were poorly fenced and badly farmed. Weeds were growing between the corn plants.

The chief walked around his village. He showed us whatever we wanted to see. Then we asked him to take us back to our island in his canoe. Ours had returned. He politely did so.—Caleb Atwater (1829) Remarks Made of A Tour to Prairie du Chien: Thence to Washington City (published 1831, pp. 60–62)

About Quashquame

Atwater thought Quashquame was about 65 years old in 1829. This means he was likely born around 1764. Quashquame was the father-in-law of the famous Meskwaki chief Taimah (Tama). Because of his role in the disputed 1804 treaty, Quashquame's power as a Sauk leader was reduced. He went from being a main chief to a minor one. People said he was "cheated out of the mineral country." Because of this, his son-in-law Taimah was chosen as chief instead.

One account says Quashquame died near Clarksville, Missouri, around 1830. It says he was short but strongly built. He was not thought to be very smart. He was also not seen as a great warrior. His influence among his people was limited. Black Hawk strongly criticized him for his part in the 1804 treaty. However, the 1830 death date might be wrong. Historical records show Quashquame attended a meeting at Fort Armstrong in late 1831. Another account from the 1870s says he died and was buried near Davenport, Iowa.

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |