1793 Philadelphia yellow fever epidemic facts for kids

In 1793, a terrible sickness called yellow fever hit Philadelphia. It was one of the worst outbreaks in United States history. Between August and November, over 5,000 people died. This was a huge number, as Philadelphia had about 50,000 residents at the time.

Many people, including government leaders, quickly left the city. About 20,000 people fled by the end of September. They did not return until the sickness ended in late November. The number of deaths was highest in October. Luckily, cold weather and frost finally killed the mosquitoes that spread the disease. This brought the outbreak to an end. Doctors back then did not know what caused yellow fever. They also did not know that mosquitoes carried the illness. This important information was only discovered much later.

The city's mayor and a special committee worked hard to help. They set up a hospital for fever patients at a place called Bush Hill. They also took other steps to manage the crisis. The Free African Society offered to help the sick. People at the time mistakenly thought that Black people might be immune to the disease. This was because some Black people had partial immunity to malaria, which was also common. Black nurses helped the sick, and their leaders hired men to move dead bodies. Most other people were too scared to touch the bodies. Sadly, Black people died from yellow fever at the same rate as white people. About 240 Black residents died in total.

Some nearby towns were afraid of the sickness. They would not let people from Philadelphia enter. Major port cities like Baltimore and New York City set up quarantines. This meant they stopped people and goods from Philadelphia from coming in. However, New York City did send money to help Philadelphia.

Contents

How the Yellow Fever Outbreak Started

In the spring of 1793, about 2,000 French refugees arrived in Philadelphia. They came from Cap Français in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti). They were escaping a slave revolution on the island. These immigrants crowded the port of Philadelphia. The city had not seen a yellow fever outbreak in 30 years.

It is very likely that these refugees and their ships carried the yellow fever virus. They also likely brought infected mosquitoes. Mosquitoes spread the virus through their bites. These insects can easily breed in small amounts of standing water. In 1793, doctors and others did not understand that mosquitoes played a role. They did not know mosquitoes spread yellow fever, malaria, and other diseases.

In port cities along the United States coast, especially in the northeast, August and September were known as the "sickly season." Fevers were common during these months. In the South, wealthy people often left their homes during this time. People believed that newcomers were more likely to get sick and die from these seasonal fevers. In 1793, Philadelphia was the temporary capital of the United States. The government was supposed to return in the fall. President George Washington left the city for his home at Mount Vernon.

The first two people to die of yellow fever in early August were recent immigrants. One was from Ireland, and the other was from Saint-Domingue. Letters describing their cases were published later. A young doctor tried to treat the Irish woman, but he was confused by her illness. His treatment did not save her.

A book from 2013 suggests that a British ship called the Hankey was the main cause of the outbreak. This ship had left Bolama, an island off West Africa, the previous November. It carried yellow fever to every port it visited in the Caribbean and along the eastern Atlantic coast.

When the Epidemic Was Declared

After two weeks, more and more people were getting sick with fever. Dr. Benjamin Rush noticed the pattern. He had been a doctor's apprentice during Philadelphia's 1762 yellow fever outbreak. He realized that yellow fever had returned. Dr. Rush warned other doctors and the government. He said the city faced a "highly contagious" and deadly yellow fever epidemic.

What made it even more alarming was that the main victims were not just the very young or very old. Many early deaths were teenagers and parents living near the docks. People believed the refugees from Saint-Domingue were bringing the disease. So, the city tried to quarantine immigrants and their goods for two to three weeks. But they could not enforce this rule as the epidemic grew.

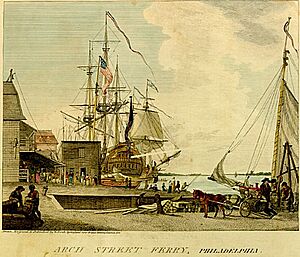

Philadelphia was the largest city in the US at the time, with about 50,000 people. It was quite small, and most houses were close to the main port on the Delaware River. The port stretched from Southwark in the south to Kensington in the north. The first cases of fever appeared near the Arch Street wharf. Dr. Rush thought that "damaged coffee which putrefied on the wharf" caused the fevers. Soon, cases also appeared in Kensington.

The port was very important for Pennsylvania's economy. So, Governor Thomas Mifflin was in charge of its health. He asked the port doctor, Dr. James Hutchinson, to check the situation. Dr. Hutchinson found that 67 out of 400 people near the Arch Street wharf were sick. But only 12 had "malignant fevers."

Dr. Rush later described some early cases. On August 7, he treated a young man with headaches, fever, and vomiting. On August 15, he treated the man's brother. On the same day, a woman he was treating turned yellow. On August 18, a man who had been sick for three days had no pulse and was cold and clammy. He was yellow but could sit up. He died a few hours later. On August 19, a woman Dr. Rush visited died within hours. Another doctor said five people near her home also died. None of these victims were recent immigrants.

The College of Physicians published a letter in the city's newspapers. It was written by a committee led by Dr. Rush. They suggested 11 ways to stop the fever from spreading. They told citizens to avoid being tired, the hot sun, night air, and too much alcohol. These things might lower their body's defenses. They also said to use vinegar and camphor often on handkerchiefs or in smelling bottles. This was for people who had to visit the sick.

They also gave advice to city officials. They suggested stopping church bells from ringing and making burials private. They also said to clean streets and wharves. They even suggested exploding gunpowder in the street to increase oxygen. Everyone should avoid touching sick people unless necessary. Crews were sent to clean the wharves, streets, and market. This made those who stayed in the city feel better. Many people who could leave the city did so.

Elizabeth Drinker, a Quaker woman, kept a journal. Her entries from August 23 to August 30 show how quickly the disease spread. They also show the rising number of deaths. She also wrote about the many people leaving the city.

Temporary Hospitals for the Sick

Like all hospitals at that time, the Pennsylvania Hospital did not accept patients with infectious diseases.

The Guardians of the Poor took over Bush Hill. This was a large 150-acre estate outside the city. Its owner, William Hamilton, was in England. Vice President John Adams had recently rented the main house. So, yellow fever patients were placed in the smaller buildings on the estate.

Panic and People Fleeing

On August 25, the College of Physicians gave their advice. Then, on September 7, Dr. Hutchinson died from yellow fever. During this time, panic spread through the city. More and more people fled. Between August 1 and September 7, 456 people died. On September 8, 42 deaths were reported. An estimated 20,000 people left the city by the end of September. This included national leaders. The daily death toll stayed above 30 until October 26. The worst week was from October 7 to 13, when 711 deaths were reported.

A publisher named Mathew Carey wrote a short book later that fall. He described how life in the city had changed:

"Those who went outside carried handkerchiefs or sponges soaked in vinegar or camphor near their noses. Others carried pieces of tarred rope or camphor bags around their necks. People quickly changed direction if they saw a hearse coming. Many walked in the middle of the streets to avoid houses where people had died. Friends avoided each other and only nodded hello. The old custom of shaking hands stopped. Many people were scared if someone offered a hand. A person wearing black clothes for mourning was avoided like a snake."

Black Nurses and Caregivers

The College of Physicians' advice suggested the fever was contagious. They said people should avoid contact with victims. However, they also said "duty" required caring for the sick. In families, if a parent was sick, they might tell their children to stay away. Dr. Rush knew that during the 1742 yellow fever outbreak in Charleston, South Carolina, African slaves seemed less affected. He thought they had a natural immunity.

Dr. Rush wrote a letter to the newspapers using the name "Anthony Benezet." This was the name of a Quaker who had taught Black children. Rush suggested that Black people in the city were immune. He asked them to "offer your services to attend the sick."

Richard Allen and Absalom Jones later wrote about their reaction to this letter:

In early September, a request appeared in the newspapers. It asked people of color to come forward and help the sick and neglected. It also suggested that people of our color were not likely to get the infection. So, we and a few others met to decide what to do. After talking, we felt free to go out. We trusted in God, knowing it was our duty to help our suffering fellow humans. We went to see where we could be useful. The first person we visited was a man in Emsley's alley who was dying. His wife was already dead in the house, and only two helpless children were there. We helped as much as we could and asked the overseers of the poor to bury the woman. We visited over twenty families that day—they were truly sad scenes! The Lord gave us strength and took away all fear from us...

To better organize our work, we met with the mayor the next day. We asked him how we could be most helpful. He first suggested focusing on the sick and finding nurses. Absalom Jones and William Gray took care of this. The mayor advised that people in need could apply to them for help. Soon after, more people died. It became very hard to find anyone to take away dead bodies, even for large rewards. People looked to the Black community for help. We then offered our services in the newspapers. We advertised that we would remove the dead and find nurses. Our services came from true kindness—we did not seek payment at first. But as the sickness grew, our work became so hard that we could not do it all ourselves.

Allen noted that as more people died, he and Jones had to hire five men to help remove bodies. Most people avoided the sick and the dead. In a letter to his wife on September 6, Dr. Rush said that the "African brethren... furnish nurses to most of my patients." Despite Dr. Rush's idea, most Black people in the city, who were born in North America, were not immune. Many slaves in Charleston in 1742 might have become immune by having a mild case of yellow fever in Africa. People who survived one attack gained immunity. In Philadelphia, 240 Black people died. This was the same rate as white people, based on their population size.

Government Actions During the Crisis

The state government ended its September meeting early. This happened after a dead body was found on the steps of the State House. Governor Mifflin became sick and was told by his doctor to leave. The city's banks stayed open. But banking was very slow because people could not pay their debts due to the epidemic. So, banks automatically extended loan payments until the epidemic ended.

Mayor Matthew Clarkson organized the city's response. Most of the city council members fled, along with 20,000 other residents. People who did not leave Philadelphia before the second week of September found it very hard to get out. They faced roadblocks, patrols, inspections, and quarantines. On September 12, Mayor Clarkson asked citizens who wanted to help the Guardians of the Poor to meet. They formed a committee to take over and deal with the crisis.

On September 14, 26 men joined Mayor Clarkson. They formed committees to reorganize the fever hospital. They also arranged visits to the sick, fed those who could not care for themselves, and arranged wagons. These wagons carried the sick to the hospital and the dead to Potter's Field, a burial ground. The Committee acted quickly. After hearing about 15-month-old twins who became orphans, they found a house for the growing number of orphans two days later. As mentioned, Richard Allen and Absalom Jones offered the help of the Free African Society members to the committee.

When the Mayor's Committee checked the Bush Hill fever hospital, they found the nurses were not trained. The hospital was very messy. "The sick, the dying, and the dead were mixed together. Waste from the sick was left in a very bad state... It was, in fact, a great human slaughter-house." On September 15, Peter Helm, a barrel maker, and Stephen Girard, a merchant born in France, volunteered to manage the hospital themselves. They also represented the Mayor's Committee.

They quickly made the hospital much better. Beds were fixed, and more were brought from the prison. This meant patients did not have to lie on the floor. A barn was turned into a place for patients who were getting better. On September 17, the managers hired 9 female nurses and 10 male attendants. They also hired a female matron. They divided the 14 rooms for male and female patients. They found a spring on the estate, and workers pumped clean water into the hospital. Helm and Girard told the Committee they could take more than the 60 patients they had. Soon, the hospital had 140 patients.

Girard found that four young doctors from the city visited only sometimes. This made patient treatment confusing. He hired Jean Devèze, a French doctor who had treated yellow fever in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti). Dr. Devèze only cared for patients at the hospital. French pharmacists helped him. Dr. Devèze admired Girard's bravery in helping the patients. In a book published in 1794, Dr. Devèze wrote about Girard:

I even saw one of the sick... throw up on him. What did Girard do? ... He wiped the patient's clothes, comforted him... arranged the bed, and gave him courage by renewing his hope that he would get better. —From him he went to another, who vomited offensive matter that would have discouraged anyone else but this wonderful man.

News that patients at the hospital were getting better made many people think that medicine was winning against the fever. But it soon became clear that many patients still died at the hospital. About 50% of those admitted passed away.

How Other Cities Reacted

As more people died in Philadelphia, officials in nearby towns and major port cities like New York and Baltimore set up quarantines. This meant they stopped people and goods from Philadelphia from entering. New York created a "Committee to prevent the spreading of infectious diseases." This committee set up patrols to watch who entered the city. Stagecoaches from Philadelphia were not allowed in many cities. For example, Havre de Grace, Maryland, tried to stop people from Philadelphia from crossing the Susquehanna River into Maryland. However, neighboring cities did send food and money. New York City, for example, sent $5,000 to the Mayor's Committee.

Some towns that accepted refugees included Woodbury and Springfield, New Jersey; Chester, Pennsylvania and Elkton, Maryland.

Carey's Accusations

In his 1793 book about the epidemic, Mathew Carey compared the sacrifices of men like Joseph Inskeep to the selfishness of others. Inskeep was a Quaker who served on the Mayor's Committee and visited the sick. When Inskeep got the fever, he asked for help from a family he had cared for when they were sick. They refused. He died, which might have happened even if they had helped him. Carey reported their refusal.

He also wrote about rumors of greedy people. He mentioned landlords who threw sick tenants into the street to take over their homes. While he praised Richard Allen and Absalom Jones for their work, he also suggested that Black people had caused the epidemic. He also claimed that some Black nurses charged too much money and even stole from the sick.

Allen and Jones quickly wrote their own pamphlet to defend the Black community. Historian Julie Winch believes they wanted to protect their community's reputation. They knew how powerful Carey was. The men pointed out that the first nurses from the Free African Society worked without pay. As more people died, they had to hire men to deal with the sick and dying. They wrote:

the high prices paid did not go unnoticed by that good and watchful leader, Matthew Clarkson, mayor of the city, and head of the committee. He sent for us and asked us to try to lower the nurses' wages. But when we told him why the prices were high (people were offering more money to get help), it was decided not to try to change anything. So, it was left up to the people involved.

Allen and Jones noted that white nurses also made money and stole from their patients. "We know that six pounds was asked for and paid to a white woman for putting a dead body into a coffin. And forty dollars was asked for and paid to four white men for carrying it downstairs." Many Black nurses served without getting paid:

"A poor Black man, named Sampson, constantly went from house to house where people were in distress and had no help, without asking for money. He got the sickness and died. After his death, his family was neglected by those he had served. Sarah Bass, a poor Black widow, helped several families as much as she could. She did not receive anything for it. And when anything was offered to her, she let those she served decide what to give."

How the Epidemic Ended

Doctors, preachers, and ordinary people all hoped autumn would end the epidemic. At first, they hoped a seasonal "equinoctial gale" or hurricane would blow the fever away. These storms were common then. Instead, heavy rains in late September seemed to lead to more cases. Residents then looked forward to freezing temperatures at night. They knew cold weather ended fall fevers, but they did not know why. By the first two weeks of October, when the crisis was at its worst, sadness filled the city. Most churches had stopped services. The post office moved away from the area with the most cases. Market days continued, and bakers kept making and selling bread. Several members of the Mayor's Committee died. African-American nurses also began dying from the fever. Carts took sick people to Bush Hill and the dead to burial grounds. Doctors also got sick and died, so fewer were available to help patients. Three of Dr. Rush's assistants and his sister died. He was too sick to leave his house. This news made people doubt Dr. Rush's treatments. However, none of those victims had followed his harsh treatment.

Those refugees from Saint-Domingue who thought they were immune walked freely in the streets. But few other residents did. Those who had not escaped the city tried to wait out the epidemic in their homes. When the Mayor's Committee quickly counted the dead, they found that most victims were poor people. They died in homes located in alleys, behind the main streets where most city business happened.

On October 16, after temperatures cooled, a newspaper reported that "the malignant fever has very considerably abated." Stores began to reopen on October 25. Many families returned, and the wharves were "once more enlivened" as a ship from London arrived with goods. The Mayor's Committee advised people outside the city to wait another week or 10 days before returning. They believed the epidemic was related to bad air. So, the Committee published instructions for cleaning closed-up houses. They suggested airing them for several days with all windows and doors open. "Burning of nitre will correct the corrupt air they may contain. Quick lime should be thrown into the outhouses and the rooms whitewashed." On October 31, a white flag was raised over Bush Hill that said, "No More Sick Persons Here."

But after some warm days, fever cases returned. The white flag had to be taken down. Finally, on November 13, stagecoaches started running north and south again. A merchant reported that the streets were "in an uproar and made the wharves impossible to use because of the huge amounts of wine, sugar, rum, coffee, cotton, etc. The porters are very smart and demand extremely high prices for anything they do." On November 14, the Mayor's Committee suggested cleaning houses, clothes, and bedding. But they said anyone could come to the city "without danger from the late prevailing disorder."

Records of the Dead

An official list of deaths showed that over 5,000 people died between August 1 and November 9, 1793. This was based on counting graves, so the real total was probably higher. City officials, doctors, religious leaders, and newspaper publishers reported the number and names of victims. This was based on the Mayor's Committee records. The online version of the Minutes has a list of all patients admitted to Bush Hill hospital and what happened to them. The publisher Mathew Carey released his history of the epidemic just weeks after it ended. He listed the names of the dead at the back of the book, which made it a bestseller.

What Caused the Fever?

Merchants were more worried about Dr. Rush's idea that the fever came from filth in Philadelphia. They did not want the port's reputation to be damaged forever. Doctors used his treatments but did not agree with his idea about the disease's origin. Others, like Dr. Devèze, did not like his treatments. But they agreed the fever started locally. Dr. Devèze had arrived on the refugee ship from Saint-Domingue. Many people blamed this ship for carrying the disease, but he thought it was healthy. Doctors at the time did not understand how the disease started or spread.

Different Treatments During the Epidemic

Dr. Kuhn suggested drinking wine, starting with lighter wines like claret. If those were not available, he suggested Lisbon or Madeira wine mixed with lemonade. The amount depended on how it affected the patient and how weak they were. He warned against increasing heat or confusion. He relied most on "throwing cool water twice a day over the naked body" to cure the disease. The patient was placed in a large tub, and two buckets of water (75 or 80 degrees Fahrenheit) were thrown on them. Dr. Edward Stevens also supported this water treatment. In mid-September, he claimed it cured Alexander Hamilton, the Secretary of the Treasury, of the fever.

Dr. Rush looked through medical books for other ways to treat the fever. Benjamin Franklin had given him letters from Dr. John Mitchell. These letters were about treating patients during a 1741 yellow fever outbreak in Virginia. Mitchell noted that the stomach and intestines filled with blood. He said these organs had to be emptied at all costs. Mitchell argued that "being too careful about the body's weakness is bad in these urgent situations... I can say that I have given a strong laxative in this case, when the pulse was so low it could hardly be felt, and the weakness was extreme, yet both were restored by it."

After trying different things, Dr. Rush decided that a powder of ten grains of calomel (mercury) and ten grains of jalap (a poisonous root from a Mexican plant) would cause the emptying he wanted. Because so many people needed his help, he had his assistants make as many of his powders into pills as they could.

On September 10, he published a guide for treating the fever. It was called "Dr. Rush's Directions for Curing and Treating the Yellow Fever." It described how people could treat themselves. At the first sign of symptoms, especially if the eyes were red or slightly yellow, and there were dull pains around the liver, he advised taking one of the powders every six hours. This was to be done until the patient had four or five large bowel movements. He urged patients to stay in bed and drink plenty of barley or chicken water. After the "bowels are thoroughly cleaned," he said it was good to take 8 to 10 ounces of blood from the arm. This was if the pulse was strong after purging. To keep the body open, he suggested more calomel or small doses of cream of tartar. If the pulse was weak, he suggested camomile or snakeroot as a stimulant. He also suggested blisters or blankets soaked in hot vinegar wrapped around the lower legs. To help the patient recover, he recommended "gruel, sago, panada, tapioca, tea, coffee, weak chocolate, wine whey, chicken broth, and white meats." He also said that seasonal fruits could be eaten. The sick room should be kept cool, and vinegar should be sprinkled on the floor.

Dr. Rush's treatment was known as "purge and bleed." As long as the patient remained weak, Dr. Rush urged more purging and bleeding. Many of his patients became unconscious. The calomel in his pills soon caused constant drooling. Dr. Rush said patients needed to drool to be cured. A sign of death was black vomit, which drooling seemed to prevent. Since he urged purging at the first sign of fever, other doctors began seeing patients with severe stomach problems. Autopsies after their deaths showed stomachs damaged by such purges.

Unlike other doctors, Dr. Devèze did not offer advice in the newspapers during the epidemic. He later discussed treatment in his book. This book included 18 patient stories and descriptions of several autopsies. While he did not like Dr. Rush's harsh purges and heavy bleeding, he did bleed patients moderately. He also used medicines to empty the bowels. Like Dr. Rush, he thought poisons had to be removed from very weak patients. Instead of purges, he used blisters to raise bumps on the skin. Unlike Dr. Kuhn, he did not like baths. He preferred to use heat, placing hot bricks on hands or feet. He strongly disagreed with the traditional treatment for severe fevers. This treatment involved wrapping patients in blankets, giving them camomile tea or Madeira wine, and trying to make them sweat. He preferred "acidulated" water instead of Peruvian bark. Many patients found the bark unpleasant.

After the Epidemic

The Governor found a middle way. He ordered the city to be kept clean. He also ordered the port to be watched to stop infected ships, or those from the Caribbean, from docking. Ships had to go through a quarantine period first. Philadelphia had more yellow fever outbreaks in 1797, 1798, and 1799. This kept the arguments about the disease's origin and treatment alive.

Some religious leaders in the city suggested the epidemic was God's judgment. Led by the Quakers, the religious community asked the state government to ban plays in the state. Such entertainment had been banned during the Revolution and only recently allowed again. After a long debate in the newspapers, the State Assembly said no to the request.

The return of yellow fever outbreaks kept discussions about causes, treatment, and prevention going until the end of the decade. Other major ports also had epidemics. Baltimore in 1794, New York in 1795 and 1798, and Wilmington and Boston in 1798. This made yellow fever a national crisis. New York doctors finally admitted they had had a yellow fever outbreak in 1791 that killed over 100 people. All the cities that suffered epidemics continued to grow quickly.

During the 1798 epidemic, Dr. Benjamin Rush traveled daily from a house just outside the city to the new city fever hospital. As the chief doctor, he treated fever victims there.

American doctors did not figure out how yellow fever was spread until the late 1800s. In 1881, Carlos Finlay, a Cuban doctor, said that mosquito bites caused yellow fever. He gave credit to Dr. Rush's book about the 1793 epidemic for giving him the idea. He said Dr. Rush had written: "Mosquitoes (the usual attendants of a sickly autumn) were uncommonly numerous..."

In the first week of September 1793, Dr. William Currie published a description of the epidemic. It also included an account of its progress during August. The publisher Mathew Carey had a book about the epidemic for sale in the third week of October, before the epidemic had even ended.

The reverends Richard Allen and Absalom Jones of the Free African Society published their own account. It argued against Carey's attacks. By that time, Carey had already published the fourth edition of his popular book. Allen and Jones noted that some Black people had worked for free. They also pointed out that Black people had died at the same rate as white people from the epidemic. And they mentioned that some white people had also overcharged for their services.

Dr. Currie's work was the first of several medical books published within a year of the epidemic. Dr. Benjamin Rush published a book over 300 pages long. Two French doctors, Jean Devèze and Nassy, published shorter accounts. Clergymen also published accounts. The most notable was by the Lutheran minister J. Henry C. Helmuth. In March 1794, the Mayor's Committee published its official records.

The quick series of other yellow fever epidemics in Philadelphia and other northeastern US cities led to many stories. These stories were about the efforts to contain, control, and deal with the disease. Dr. Rush wrote about the 1797, 1798, and 1799 epidemics in Philadelphia. He changed his account of the 1793 epidemic to remove any mention of the disease being contagious. He also changed his cures. In 1798, he was appointed as the chief doctor at the fever hospital. The death rate that year was about the same as it had been at Bush Hill in 1793. This was true even though the treatments used were very different.

Noah Webster, a well-known New York newspaper publisher, joined two doctors to publish the Medical Repository. This was a magazine that collected stories of fever epidemics across the nation. Webster used this information in his 1798 book. He suggested that the nation was experiencing a widespread "epidemic constitution" in the air. He thought this might last 50 years and make deadly epidemics almost certain. Deaths were especially high in Philadelphia. This fact, along with the disease spreading between Boston and Charleston from 1793 to 1802, made yellow fever a national crisis. Thomas A. Apel wrote that "Yellow fever was the most urgent national problem of the early national period. [...] Yellow fever harmed public good, which was the foundation of a healthy republic."

Later 20th-century US history books, like the 10-volume Great Epochs in American History (1912), used short parts from Carey's account. The first history of the epidemic that used more original sources was J. H. Powell's Bring Out Your Dead (1949). While Powell did not write a scholarly history, his work showed its historical importance. Since the mid-1900s, scholars have studied different parts of the epidemic. For example, Martin Pernick's paper "Politics, Parties, and Pestilence: Epidemic Yellow Fever in Philadelphia and the Rise of the First Party System," used statistics. It showed that doctors who supported the Republican party generally used Dr. Rush's treatments. Doctors who supported the Federalist party used Dr. Kuhn's.

Scholars celebrated the 200th anniversary of the epidemic. They published papers on various aspects of the outbreak. A 2004 paper in the Bulletin of the History of Medicine looked again at Dr. Rush's use of bleeding.

See also

- Philadelphia Lazaretto, a quarantine hospital built in 1799 because of the 1793 epidemic

- Stubbins Ffirth

- History of yellow fever

- List of notable disease outbreaks in the United States

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |