2009 swine flu pandemic facts for kids

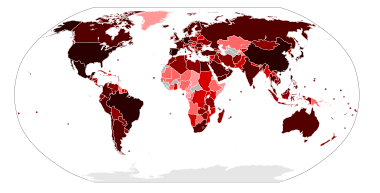

50,000+ confirmed cases 5,000–49,999 confirmed cases 500–4,999 confirmed cases 50–499 confirmed cases 5–49 confirmed cases 1–4 confirmed cases No confirmed cases

|

|

|

|

|

| Disease | Influenza |

|---|---|

| Virus strain | Pandemic H1N1/09 virus |

| Location | Worldwide |

| First case | Veracruz, Mexico |

| Arrival date | September 2008 |

| Date | January 2009 – 10 August 2010 |

| Origin | North America |

| Confirmed cases | 491,382 (lab-confirmed) |

| Suspected cases‡ | 700 million to 1.4 billion (estimate) |

|

Deaths

|

Lab confirmed deaths: 18,449 (reported to the WHO) Estimated excess death: 284,000 |

| ‡ Suspected cases have not been confirmed as being due to this strain by laboratory tests, although some other strains may have been ruled out. | |

The 2009 swine flu pandemic was a worldwide outbreak of a new type of influenza virus. It was caused by the H1N1 virus. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared it a pandemic from June 2009 to August 2010. This was the third time the H1N1 virus caused a major flu pandemic. The first two were the 1918 Spanish flu and the 1977 Russian flu.

The first two cases of this new flu were found in the United States in April 2009. Scientists found that this H1N1 virus was a mix of flu viruses from birds, pigs, and humans. It also had parts from a flu virus found in pigs in Europe and Asia. This is why it was often called "swine flu."

Many people got sick during this pandemic. Some studies suggest that between 700 million and 1.4 billion people might have been infected. This was about 11% to 21% of the world's population at the time. The number of deaths confirmed by labs was 18,449. However, experts believe the actual number of deaths was much higher. Later estimates suggested around 284,000 people died because of this flu.

Unlike most flu types, this H1N1 virus affected younger adults more than older adults (over 60). Even healthy people could get very sick. Some developed serious lung problems like pneumonia. This often happened a few days after flu symptoms started. Doctors recommended special medicines for flu patients with pneumonia.

Contents

- What is the 2009 H1N1 Flu?

- When Did the 2009 H1N1 Flu Start?

- What Are the Symptoms of H1N1 Flu?

- How Was H1N1 Flu Diagnosed?

- What Caused the H1N1 Flu?

- How Was H1N1 Flu Prevented?

- How Was H1N1 Flu Treated?

- How Many People Were Affected by H1N1 Flu?

- How Does H1N1 Compare to Other Pandemics?

- Images for kids

- See also

What is the 2009 H1N1 Flu?

The World Health Organization (WHO) officially called this event the "(H1N1) 2009 pandemic." The virus itself was named "A(H1N1)pdm09" in 2010.

There was some confusion and debate about what to call the flu. People used names like "H1N1 flu," "Swine flu," and "Mexican flu." Some thought "H1N1" was too technical. Others worried that "swine flu" made people think they could get sick from eating pork. This was not true. Also, "Mexican flu" caused some people to unfairly blame or stereotype people from Mexico.

Different health groups used different names. The CDC in the U.S. used "novel influenza A (H1N1)." Other groups tried names like "Pig Flu" or "North American influenza." This made it even more confusing for everyone.

When Did the 2009 H1N1 Flu Start?

Scientists believe the virus first jumped from pigs to humans in 2008. This likely happened around September 2008. It seems the virus was present in pigs for several months before the outbreak was noticed. This showed the need for better checks on animal health.

The first widespread infections were noticed in Veracruz, Mexico. The virus had probably been there for months before it was officially called an "epidemic." The Mexican government closed many public places in Mexico City to try and stop the spread. But the virus continued to spread around the world.

The new virus was first identified in April 2009. This happened when labs in the U.S. and Canada tested samples from sick people in Mexico and the U.S. The earliest known human case was a 5-year-old boy in La Gloria, Mexico, on March 9, 2009.

In April, the WHO declared a "public health emergency of international concern." This means it was a serious global health threat. By June, the WHO and CDC stopped counting individual cases. They declared the outbreak a pandemic.

Even though it was called "swine flu," you could not get it from eating pork. It spread from person to person, mainly through coughing or sneezing. Symptoms usually lasted 4 to 6 days. Special antiviral medicines were suggested for those with severe symptoms.

The pandemic started to slow down in November 2009. By May 2010, cases were dropping fast. On August 10, 2010, the WHO announced the pandemic was over. They said the H1N1 event was now in a "post-pandemic period."

What Are the Symptoms of H1N1 Flu?

The symptoms of H1N1 flu are much like those of other flu types. They can include:

- Fever

- Cough (often a dry cough)

- Headache

- Dizziness

- Sneezing

- Muscle or joint pain

- Sore throat

- Chills

- Feeling very tired

- Runny nose

Some people also reported diarrhea, vomiting, or nerve problems.

Who is at Higher Risk?

Some people were more likely to get very sick from H1N1 flu. These included:

- People over 65 (though this flu affected younger people more than typical flu)

- Children younger than 5

- Children with certain brain or muscle conditions

- Pregnant women (especially in their last three months)

- People with ongoing health problems like asthma, diabetes, obesity, heart disease, or a weak immune system.

More than 70% of people hospitalized in the U.S. had these underlying health issues.

Severe Cases and Complications

In severe cases, patients often got worse quickly. This usually happened three to five days after symptoms started. Many needed help breathing with machines in the hospital's intensive care unit.

The flu could cause pneumonia, which is a serious lung infection. This could be caused directly by the virus or by a bacterial infection that followed the flu. Bacterial infections were more common in children.

Some studies found that people who were very overweight or had lung problems were more likely to get seriously ill. Most deaths in hospitals happened to people who were healthy before getting the flu.

How Was H1N1 Flu Diagnosed?

To confirm H1N1 flu, doctors took a swab from a patient's nose or throat. A special test called RT-PCR was recommended. This test could tell the difference between H1N1 and regular seasonal flu.

However, most people with flu symptoms did not need this specific test. The results usually did not change how they were treated. The U.S. CDC suggested testing mainly for:

- People in the hospital with suspected flu.

- Pregnant women.

- People with weak immune systems.

Doctors were advised not to wait for test results to start treatment. They should decide based on symptoms and how the flu was spreading.

What Caused the H1N1 Flu?

The H1N1 virus was a new type of flu. Regular flu vaccines did not offer much protection against it. Studies showed that children had no protection against this new strain. Older adults (over 60) had some protection, possibly from being exposed to similar flu viruses in the past.

Scientists looked at the virus's genes. They found it had genes from five different flu viruses. These included flu viruses from pigs in North America, birds in North America, humans, and pigs in Asia and Europe.

This H1N1 virus was less deadly than the 1918 Spanish flu. The 1918 flu killed about 2-3% of those infected. The 2009 H1N1 flu killed about 0.01-0.03% of those infected. However, it still caused many hospitalizations and deaths, especially in people under 50.

In 2010, scientists found a new swine flu virus in Hong Kong. It was a mix of the pandemic H1N1 virus and other pig flu viruses. This showed that the pandemic virus could mix with other viruses in pigs. Pigs are sometimes called "mixing vessels" for flu. This is because they can get infected by both bird flu and human flu viruses. When this happens, the viruses can swap genes and create new types that can spread to humans.

How Did H1N1 Flu Spread?

The H1N1 virus spread in the same way as seasonal flu. It mainly spread from person to person through coughing or sneezing. People could also get infected by touching surfaces with flu viruses on them, then touching their face.

The virus was also found to spread to animals. These included pigs, turkeys, ferrets, cats, dogs, and even a cheetah.

How Was H1N1 Flu Prevented?

When the H1N1 vaccine first came out, there wasn't enough for everyone. So, health groups like the CDC recommended giving it to certain groups first. These included:

- Pregnant women.

- People living with or caring for babies under six months old.

- Children aged six months to four years.

- Healthcare workers.

At first, it was thought two vaccine shots would be needed. But studies showed that one shot was enough for adults. This meant more people could get vaccinated with the limited supply.

Health officials were worried the virus might change and become more dangerous. They urged communities and businesses to make plans. These plans included what to do if schools closed or many employees got sick.

In 2010, the CDC recommended that everyone over six months old in the U.S. get a flu vaccine. The flu vaccine now protects against the 2009 H1N1 virus and other flu viruses.

Vaccines and Safety

By late 2009, vaccines were given in over 16 countries. Studies showed that the 2009 H1N1 vaccine was as safe as the regular seasonal flu vaccine.

A 2013 study by the CDC estimated that the H1N1 vaccine saved about 300 lives in the U.S. It also prevented about a million illnesses. The study suggested that if the vaccine program had started two weeks earlier, many more cases could have been prevented.

Concerns About Vaccine Production

There were some concerns about how the vaccine was handled. Some experts pointed out that some people advising the WHO had financial ties to drug companies. These companies made antivirals and vaccines. The WHO stated that its decisions were based on scientific facts, not on helping drug companies. They also welcomed a review of their actions.

How to Control the Spread of Infection

Travel

The WHO said it was not possible to completely stop the virus from spreading through travel. They did not recommend closing borders. However, some countries did take steps. For example, China quarantined visitors from flu-affected areas who had flu-like symptoms.

Airports used thermal cameras to check for fevers. Some airlines increased cabin cleaning and allowed staff to wear masks. However, studies later showed that checking people for flu symptoms at airports was not very effective.

Schools

U.S. officials were especially concerned about schools. The H1N1 virus seemed to affect young people (ages six months to 24 years) more.

Instead of closing schools, the CDC suggested that sick students and staff stay home. They should stay home for seven days, or until 24 hours after symptoms were gone, whichever was longer. Schools were also advised to have a room for sick students to wait before going home. They also suggested that sick students or staff wear face masks.

Many schools planned to stock up on medical supplies. They also made plans for school closures, like providing lessons and meals for low-income children at home. By October 2009, about 600 schools in the U.S. had temporarily closed.

Workplace

Governments also gave advice to employers. They suggested that businesses plan for many employees being sick. They also advised that sick workers stay home for seven days, or 24 hours after symptoms ended.

Face Masks

The U.S. CDC did not recommend face masks for everyone in public places. They suggested them for sick people around others, or for people at high risk who were caring for someone with the flu.

There was some debate about how useful masks were. Some experts worried that masks might give people a false sense of safety. They stressed that other precautions, like handwashing, were still very important. Masks are common in Asia, especially in Japan, where people wear them to avoid spreading germs when they are sick.

Quarantine

During the pandemic, some countries quarantined visitors who might have been infected. China confined U.S. students and teachers to their hotel rooms. Australia kept a cruise ship at sea. Egypt ordered the slaughter of all pigs. Russia and Taiwan said they would quarantine visitors with fevers. Japan also quarantined airline passengers.

Pigs and Food Safety

The pandemic virus came from pigs, which is why it was called "swine flu." However, health experts made it clear that eating properly cooked pork or other pig products would not cause the flu. Despite this, some countries banned importing pig products. For example, Azerbaijan banned imports from the Americas. The Egyptian government even ordered all pigs in Egypt to be killed.

How Was H1N1 Flu Treated?

Most people with H1N1 flu recovered without special medical care. Simple steps like drinking plenty of fluids and resting helped ease symptoms. Over-the-counter pain medicines like paracetamol and ibuprofen could help reduce fever and pain. However, aspirin should not be given to children under 16 with flu symptoms because of a rare but serious risk called Reye's Syndrome.

For people at higher risk of serious problems, antiviral medicines like oseltamivir or zanamivir were recommended. These medicines work best if taken within 48 hours of symptoms starting. They could help reduce the severity of the illness. If someone developed pneumonia, they were given both antivirals and antibiotics.

The CDC advised against using antivirals too much. This was to prevent the virus from becoming resistant to the medicines.

Side Effects of Treatment

Antiviral medicines can have side effects. These include feeling lightheaded, chills, nausea, vomiting, and trouble breathing. Some children were reported to have confusion after taking oseltamivir. The WHO warned people not to buy antivirals from online pharmacies without a physical address, as many were fake.

Resistance to Antivirals

By 2012, some samples of the H1N1 flu virus showed resistance to oseltamivir (Tamiflu). This meant the medicine might not work as well against those specific virus strains. However, no flu virus had shown resistance to zanamivir (Relenza), another antiviral medicine.

How Many People Were Affected by H1N1 Flu?

| Area | Lab confirmed deaths reported to the WHO |

|---|---|

| Worldwide (total) | At least 18,449 |

| Africa | 168 |

| Americas | At least 8,533 |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 1,019 |

| Europe | At least 4,079 |

| South-East Asia | 1,992 |

| Western Pacific | 1,858 |

| Further information: Cases and deaths by country

Note: The ratio of confirmed deaths to total deaths due to the pandemic is unknown. For more information, see "Data reporting and accuracy". |

|

It's hard to know exactly when or where the H1N1 virus first appeared. Scientists think it started circulating among humans in September 2008. It was several months before it was officially identified.

Cases in Mexico

The virus was first reported in two U.S. children in March 2009. But health officials believe it infected people in Mexico as early as January 2009. The outbreak was first officially identified in Mexico City on March 18, 2009. Mexico quickly told the U.S. and WHO about it. Mexico City was largely shut down to try and stop the spread.

Cases in the United States

The CDC first identified the new strain in two children in California in April 2009. Neither child had been in contact with pigs. The first confirmed death from H1N1 flu in the U.S. was a toddler from Mexico City. This child was visiting family in Texas.

How Data Was Reported

Counting flu cases and deaths is tricky. For example, in June 2009, the U.S. had nearly 28,000 lab-confirmed cases. But experts estimated that about 1 million Americans actually had the flu at that time. This is because many mild cases were not tested or reported.

The number of deaths from flu is also hard to count. Flu is often not listed as the cause of death on death certificates. So, the official numbers are usually much lower than the actual number of deaths caused by flu. The WHO stated that the total deaths from H1N1 were "unquestionably higher" than the confirmed numbers.

In July 2009, the WHO stopped counting individual cases. They focused more on major outbreaks instead. This was because the number of lab-confirmed cases was not showing the full picture.

What We Learned Later

A study in September 2010 found that the 2009 H1N1 flu was not more severe than seasonal flu. The risk of serious problems was not higher for adults or children. Children were affected more often, but their symptoms were not necessarily worse.

The CDC estimated that from April 2009 to April 2010 in the U.S.:

- Between 43 million and 89 million people got H1N1 flu.

- Between 195,000 and 403,000 people were hospitalized.

- Between 8,870 and 18,300 people died.

These numbers are similar to or lower than the average deaths from seasonal flu in the U.S. each year. Seasonal flu deaths can range from about 3,000 to 49,000 annually.

Hospitals in the U.S. made big plans to handle many patients during the pandemic. They were often successful in treating those most severely affected. For example, the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia used extra spaces for patients and brought in more staff.

How Does H1N1 Compare to Other Pandemics?

Every year, flu epidemics affect 5-15% of the world's population. They cause severe illness in 3-5 million people and 290,000-650,000 deaths worldwide. In rich countries, severe illness and deaths usually happen in babies, older people, and those with long-term illnesses. However, the 2009 H1N1 flu, like the 1918 Spanish flu, affected younger, healthier people more.

The 20th century saw three major flu pandemics:

- The Spanish flu in 1918.

- The Asian flu in 1957.

- The Hong Kong flu in 1968–69.

These pandemics happened because the flu viruses changed a lot. People did not have much protection against these new strains.

The 1918 Spanish flu started mildly in spring. But then, more deadly waves came in the autumn. It killed hundreds of thousands in the U.S. and 50-100 million worldwide. Most deaths were from bacterial pneumonia that followed the flu. Today, antibiotics can treat pneumonia, which helps reduce deaths in pandemics.

| Name | Date | World pop. | Subtype | Reproduction number | Infected (est.) | Deaths worldwide | Case fatality rate | Pandemic severity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spanish flu | 1918–20 | 1.80 billion | H1N1 | 1.80 (IQR, 1.47–2.27) | 33% (500 million) or >56% (>1 billion) | 17 –100 million | 2–3%, or ~4%, or ~10% | 5 |

| Asian flu | 1957–58 | 2.90 billion | H2N2 | 1.65 (IQR, 1.53–1.70) | >17% (>500 million) | 1–4 million | <0.2% | 2 |

| Hong Kong flu | 1968–69 | 3.53 billion | H3N2 | 1.80 (IQR, 1.56–1.85) | >14% (>500 million) | 1–4 million | <0.2% | 2 |

| 1977 Russian flu | 1977–79 | 4.21 billion | H1N1 | ? | ? | 0.7 million | ? | ? |

| 2009 swine flu pandemic | 2009–10 | 6.85 billion | H1N1/09 | 1.46 (IQR, 1.30–1.70) | 11–21% (0.7–1.4 billion) | 151,700–575,400 | 0.01% | 1 |

| Typical seasonal flu | Every year | 7.75 billion | A/H3N2, A/H1N1, B, ... | 1.28 (IQR, 1.19–1.37) | 5–15% (340 million – 1 billion) 3–11% or 5–20% (240 million – 1.6 billion) |

290,000–650,000/year | <0.1% | 1 |

| Notes | ||||||||

People who had the flu before 1957 seemed to have some protection against the 2009 H1N1 flu. This was because they had antibodies that could fight the new virus.

A 2012 study estimated that the actual number of deaths from the 2009 H1N1 flu might have been 15 times higher than reported. Most of these deaths (80%) were in people younger than 65. Also, 51% of deaths happened in Southeast Asia and Africa. This shows that efforts to prevent future flu pandemics need to focus on these regions.

The COVID-19 pandemic is different. It is caused by a coronavirus, not an influenza virus. But it also mainly affects the breathing system.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Pandemia de gripe A (H1N1) de 2009-2010 para niños

In Spanish: Pandemia de gripe A (H1N1) de 2009-2010 para niños

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |