Ernst Nolte facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ernst Nolte

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 11 January 1923 |

| Died | 18 August 2016 (aged 93) Berlin, Germany

|

| Nationality | German |

| Education | PhD in Philosophy (1952) |

| Alma mater | University of Münster University of Berlin University of Freiburg University of Cologne |

| Occupation | Philosopher, historian |

| Employer | University of Marburg (1965–1973) Free University of Berlin (since 1973, Emeritus since 1991) |

| Known for | Articulating a theory of generic fascism as “resistance to transcendence”, and for his involvement in the Historikerstreit debate |

| Spouse(s) | Annedore Mortier |

| Children | Georg Nolte |

| Awards | Hanns Martin Schleyer Prize (1985) Konrad Adenauer Prize (2000) Gerhard Löwenthal Honor Award (2011) |

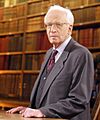

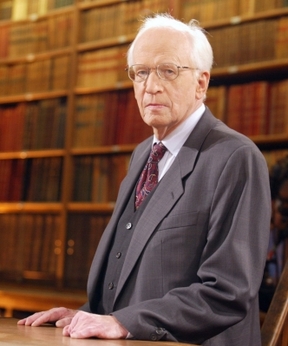

Ernst Nolte (born January 11, 1923 – died August 18, 2016) was a German historian and philosopher. He was very interested in comparing fascism and communism. Nolte taught modern history at the Free University of Berlin from 1973 until he retired in 1991. Before that, he was a professor at the University of Marburg.

He became well-known for his book Fascism in Its Epoch, published in 1963. Nolte was a leading conservative thinker. He was involved in many debates about how to understand the history of fascism and communism. One famous debate was the Historikerstreit in the late 1980s. Later in his life, Nolte also studied Islamism.

Nolte received several awards for his work. His son, Georg Nolte, is a well-known legal scholar.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Ernst Nolte was born in Witten, Germany. His family was Roman Catholic. When he was seven, he read a Soviet children's book that criticized the Catholic Church. This made him angry and was his first encounter with communism.

In 1941, Nolte could not join the military because of a hand injury. He decided to study Philosophy, Philology (the study of language), and Greek. He attended universities in Münster, Berlin, and Freiburg. At Freiburg, he was a student of Martin Heidegger, a famous philosopher who greatly influenced him.

After 1945, Nolte worked as a high school teacher. In 1952, he earned his PhD in philosophy. His thesis was about "Self Alienation and the Dialectic in German Idealism and Marx." After this, he began studying contemporary history. He published his important book, Der Faschismus in seiner Epoche, in 1963.

Nolte married Annedore Mortier. They had a son, Georg Nolte.

Understanding Fascism in Its Epoch

Nolte became famous with his 1963 book, Der Faschismus in seiner Epoche. This book was translated into English as The Three Faces of Fascism. In it, he suggested that fascism appeared as a way to resist and react against modernity (the modern world).

Nolte believed that history had a "metapolitical dimension." This means that big ideas act as powerful spiritual forces that influence society. He thought that only philosophers could truly understand this deeper meaning of history. Nolte studied German Nazism, Italian Fascism, and the French Action Française movements.

He concluded that fascism was a major "anti-movement." It was against liberalism, anti-communist, anti-capitalist, and against middle-class values. For Nolte, fascism was a rejection of many things the modern world offered. He saw it as a negative force.

Nolte explained that fascism worked on three levels:

- In politics, it opposed Marxism.

- In society, it opposed middle-class values.

- In the "metapolitical" world, it was "resistance to transcendence." "Transcendence" here means the "spirit of modernity."

Nolte said that fascism was "anti-Marxism." It tried to destroy its enemy by using similar methods but always within a national framework.

He defined "transcendence" as a force with two types of change. "Practical transcendence" meant material progress, new technology, and social equality. This is how humanity frees itself from old, strict societies. "Theoretical transcendence" meant trying to go beyond what exists, aiming for a new future. This removes old limits on the human mind.

Nolte used the flight of Yuri Gagarin into space in 1961 as an example of "practical transcendence." It showed how humans were advancing technologically and gaining powers once thought only for gods. Nolte argued that this progress caused fear. This fear of the old world being replaced by the new led to fascism.

Regarding the Holocaust, Nolte believed that Adolf Hitler saw Jewish people as connected to modernity. Because Hitler hated modernity, his policies against Jewish people always aimed at genocide. Nolte thought Hitler was "logically consistent" in seeking to kill Jewish people because he hated what they represented to him.

Nolte's book was praised for creating a new way to understand fascism based on ideas. It moved away from earlier ideas that focused only on social and economic reasons. However, some critics, like Sir Ian Kershaw, said Nolte focused too much on ideas and not enough on social and economic conditions. They also said he relied too much on writings by fascists.

Later, in the 1970s, Nolte changed some of his views. He started to see Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union as similar "totalitarian" states. He believed Nazi Germany was a "mirror image" of the Soviet Union. He claimed that, except for the "technical detail" of gas chambers, everything the Nazis did had already been done by communists in Russia.

Nolte's Historical Approach

Nolte's historical work was greatly shaped by German philosophy. He tried to find the main ideas that drove all of history. He focused on general patterns rather than specific details of a time period.

For example, in his 1974 book Deutschland und der kalte Krieg (Germany and the Cold War), Nolte looked at the division of Germany after 1945. He didn't just study the Cold War itself. Instead, he looked at other divided states throughout history. He saw Germany's division as the ultimate example of the "metapolitical" idea of division caused by competing beliefs.

Nolte believed that ideas have their own power. Once a new idea appears, it cannot be ignored. He saw the Cold War as a global conflict between different powerful beliefs. He called it "the ideological and political conflict for the future structure of a united world."

The Historians' Dispute (Historikerstreit)

Nolte's Controversial Ideas

Nolte is most famous for starting the Historikerstreit ("Historians' Dispute") in 1986-1987. On June 6, 1986, he published an opinion piece called "The Past That Will Not Pass." In it, he said it was time to move past the "negative myth" of Nazi Germany. He felt that too much focus on the Nazi era took attention away from current problems.

Nolte argued that the Russian Revolution of 1917 was the most important event of the 20th century. He believed it started a long civil war in Europe that lasted until 1945. For Nolte, fascism was a desperate response by Europe's middle classes to the "Bolshevik peril" (the threat of communism). He suggested that to understand the Holocaust, one should also look at the Industrial Revolution and the rule of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia.

In his 1987 book, Der europäische Bürgerkrieg, 1917–1945 (The European Civil War, 1917–1945), Nolte claimed that Germany was Europe's best hope for progress between the world wars. He argued that if Germany had remained disarmed after the Treaty of Versailles, it would have been destroyed. This, he said, would have ended any hope for a "United States of Europe."

Criticism from Jürgen Habermas

The philosopher Jürgen Habermas strongly criticized Nolte in July 1986. Habermas accused Nolte of trying to "apologize" for the Nazi era. He also said Nolte was trying to "close Germany's opening to the West" that had existed since 1945.

Habermas especially criticized Nolte for suggesting that the Holocaust was morally similar to the Khmer Rouge genocide. Habermas argued that Cambodia was a poor, farming country, while Germany was a modern, industrial state. Therefore, he believed the two genocides could not be compared.

Later Work and Debates

In his 1991 book, Geschichtsdenken im 20. Jahrhundert (Historical Thinking in the 20th Century), Nolte said the 20th century had three "extraordinary states": Germany, the Soviet Union, and Israel. He claimed that while Germany and the Soviet Union were now "normal," Israel was still "abnormal." He worried it might become a fascist state and commit genocide against Palestinians.

Between 1995 and 1997, Nolte exchanged letters with French historian François Furet. They debated the link between fascism and communism. Furet agreed that comparing communism and Nazism was important. He noted that Nolte's ideas challenged common views about guilt and anti-fascism. Their letters were published as a book, Fascism and Communism, in 2001.

Nolte often wrote opinion pieces for German newspapers. He was seen as one of Germany's "most brooding" thinkers about history.

In June 2006, Nolte gave an interview where he called Islamic fundamentalism a "third variant" of "resistance to transcendence." He saw it as similar to communism and National Socialism. He also said he was a philosopher, not a historian. He believed this was why historians often reacted negatively to his work.

Historian Norman Davies supported Nolte's ideas in his 2006 book, Europe at War 1939–1945: No Simple Victory. Davies wrote that fascism should be seen as a "counter-revolution" against communism. He also said that some Nazi methods were copied from the Soviet Union. Davies concluded that later information about Soviet crimes made Nolte's critics seem less correct.

Awards

- Hanns Martin Schleyer Prize (1985)

- Konrad Adenauer Prize (2000)

- Gerhard Löwenthal Honor Award (2011)

Images for kids

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |