Ian Kershaw facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sir Ian Kershaw

|

|

|---|---|

Kershaw at the 2012 Leipzig Book Fair

|

|

| Born | 29 April 1943 Oldham, Lancashire, England

|

| Alma mater | |

| Spouse(s) | Betty Kershaw |

| Children | 2 |

| Parent(s) | Joseph Kershaw, Alice (Robinson) Kershaw |

| Scientific career | |

| Thesis | Bolton Priory, 1286–1325: An Economic Study (1969) |

| Influences |

|

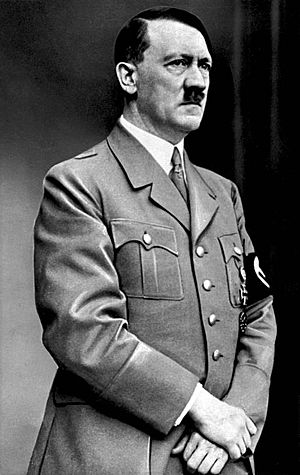

Sir Ian Kershaw is a famous English historian. He is known for his work on the social history of 20th-century Germany. Many people consider him one of the top experts on Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany. He is especially famous for his books about Hitler's life.

Sir Ian Kershaw followed the ideas of German historian Martin Broszat. Before he retired, he was a professor at the University of Sheffield. He often called Broszat an "inspirational mentor" who greatly helped him understand Nazi Germany. Kershaw also worked as a history advisor for many BBC documentaries. These included The Nazis: A Warning from History and War of the Century.

Contents

Early Life and Studies

Ian Kershaw was born on April 29, 1943, in Oldham, England. His father, Joseph Kershaw, was a musician. Ian went to Counthill Grammar School and St Bede's College, Manchester. He later studied at the University of Liverpool and Merton College, Oxford.

From Medieval to Modern History

Kershaw first studied medieval history, which is about the Middle Ages. But in the 1970s, he started studying modern German social history. This change happened after a surprising event in 1972. He was in Munich, Germany, and met an old man in a café. The man told him that the English were foolish for not siding with Germany. He also said, "The Jew is a louse!" This conversation shocked Kershaw. It made him want to understand why ordinary people in Germany supported Nazism.

Family Life

Sir Ian Kershaw's wife is Dame Betty Kershaw. She was a professor of nursing and a dean at the University of Sheffield.

Understanding Nazi Germany

In 1975, Kershaw joined the "Bavaria Project" with Martin Broszat. This project helped him look at how everyday people saw Hitler. His work led to his first book about Nazi Germany.

The "Hitler Myth"

Kershaw's first book was The "Hitler Myth": Image and Reality in the Third Reich. It was published in German in 1980. The book explored the "Hitler cult" in Germany. It showed how Joseph Goebbels created a powerful image of Hitler. It also looked at who believed in this "myth" and how it grew and faded.

Everyday Life Under the Nazis

Another book from the "Bavaria Project" was Popular Opinion and Political Dissent in the Third Reich. This 1983 book looked at how ordinary people in Bavaria experienced the Nazi era. Kershaw showed how people followed the rules and how much they dared to disagree. He described most Bavarians as "the muddled majority." They were not fully Nazi supporters nor strong opponents.

Kershaw found that most Bavarians cared more about their daily lives than politics. He also concluded that most Bavarians were either against Jewish people or simply did not care what happened to them. He noted that most violent acts against Jewish people, like the Kristallnacht attack, were done by a small group of strong Nazi members. Kershaw famously said that "the road to Auschwitz was built by hate, but paved with indifference." This meant that many people's lack of caring allowed terrible things to happen.

Debate on German Attitudes

Kershaw's idea that most Germans were "indifferent" to the Shoah (the Holocaust) was debated. Historians like Otto Dov Kulka and Michael Hans Kater disagreed. They argued that Germans were more against Jewish people than Kershaw suggested. Kulka thought "passive complicity" (quietly going along with it) was a better term than "indifference."

Studying the Nazi Dictatorship

In 1985, Kershaw published The Nazi Dictatorship: Problems and Perspectives of Interpretation. In this book, he looked at the different ways historians understood Nazi Germany.

Different Views of History

Kershaw explained that historians had many different ideas about the Nazi era. For example, some saw Nazism as a result of German history. Others, like Marxists, saw it as a result of capitalism. He also discussed the debate between "functionalists" and "intentionalists."

- Functionalists believed the Holocaust happened step-by-step, due to the way the Nazi government worked.

- Intentionalists believed Hitler planned the Holocaust from the very beginning.

Kershaw thought it was important to understand these different views. He also believed it was fair to compare Nazi Germany with the Soviet Union under Stalin, even though they had many differences.

Influences and Debates

Kershaw was influenced by historians like Martin Broszat and Hans Mommsen. He agreed with the idea that German big businesses served the Nazi government, rather than the other way around.

He also took part in the Historikerstreit (Historians' Dispute) in the late 1980s. He disagreed with historians who he felt were trying to make Germany's past seem less bad. Kershaw argued that Nazism should be seen as a very extreme type of fascism.

How Hitler's Power Worked

Kershaw believed that the way the Nazi state was set up was more important than just Hitler's personality. He, like Broszat and Hans Mommsen, saw Nazi Germany as a messy mix of different government groups always fighting for power. Kershaw thought the Nazi government was not a single, strong unit. Instead, it was a group of powerful parts like the Nazi Party, big businesses, the army, and the SS. These groups often fought each other.

Hitler's Role

For Kershaw, Hitler's real importance came from how the German people saw him. In his books about Hitler, Kershaw described him as a rather ordinary person. He disagreed with the idea that Hitler was a "great man" who single-handedly caused everything. Kershaw argued that it's wrong to explain Germany's history just through one person, especially when sixty-eight million people were involved.

Kershaw also did not like theories that tried to explain the Holocaust or World War II by saying Hitler had a medical problem. He believed such ideas made it seem like one person was responsible for everything, instead of looking at the bigger picture of Nazi Germany.

Charismatic Leadership

Kershaw's books about Hitler looked at how Hitler gained and kept his power. He argued that Hitler's leadership was a perfect example of Max Weber's idea of "charismatic leadership." This means people followed Hitler because they believed he had special qualities.

Kershaw saw the Nazi regime as part of a larger crisis in Europe from 1914 to 1945. He believed that the Holocaust was not a single plan from the start. Instead, it was a process that grew more extreme over time. This idea is called "cumulative radicalization." It means that as different Nazi groups competed for power, they came up with increasingly harsh solutions, especially for the "Jewish Question."

"Working Towards the Führer"

Kershaw disagreed with the idea that Hitler was a "weak dictator" who didn't do much. But he did agree that Hitler wasn't involved in the daily running of the government. Kershaw explained this with his theory called "Working Towards the Führer." This phrase came from a 1934 speech by a German official.

The idea is that officials in Nazi Germany often took action on their own. They tried to guess what Hitler wanted or to make his vague ideas into real policies. They did this to gain his approval. Kershaw called Hitler a "lazy dictator" who wasn't very interested in daily tasks. The only areas Hitler focused on were foreign policy and military decisions.

Kershaw argued that Hitler's power was based on his charisma, not on a strict government system. This led to a breakdown of order in Germany. By 1938, the German government was a mess of competing groups. Each group tried to get Hitler's favor, which was the only way to have power. This competition led to the "cumulative radicalization" of Germany. German officials, trying to please Hitler, carried out more and more extreme actions, especially regarding the "Jewish Question."

As an example, Kershaw used Hitler's order to two Nazi leaders, Albert Forster and Arthur Greiser. Hitler told them to make parts of Poland "German" within 10 years and said "no questions would be asked" about how they did it. Forster simply had Poles sign forms saying they had "German blood." But Greiser carried out a brutal plan to remove Poles from his area. This showed how Hitler set things in motion, and how his leaders used different, often extreme, methods to achieve what they thought Hitler wanted.

Historian Otto Dov Kulka praised the "Working Towards the Führer" idea. He said it was the best way to understand how the Holocaust happened. It combined the best parts of both the "functionalist" and "intentionalist" theories.

Later Career and Works

Sir Ian Kershaw retired from full-time teaching in 2008. In recent years, he has written two books about the broader history of Europe. These are To Hell and Back: Europe, 1914–1949 and Rollercoaster: Europe, 1950–2017.

Awards and Recognition

Sir Ian Kershaw has received many honors for his work:

- He is a Fellow of the British Academy.

- He received the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1994.

- He won the Wolfson History Prize in 2000 for his book Hitler, 1936–1945: Nemesis.

- He was made a Knight Bachelor in 2002 for his contributions to history.

- In 2005, he won the Elizabeth Longford Prize for Historical Biography.

- He received the Leipzig Book Award for European Understanding in 2012.

- He was awarded the Charlemagne Medal in 2018.

Books by Sir Ian Kershaw

- Bolton Priory. The Economy of a Northern Monastery (1973)

- Popular Opinion and Political Dissent in the Third Reich. Bavaria, 1933–45 (1983)

- The Nazi Dictatorship. Problems and Perspectives of Interpretation (1985)

- The "Hitler Myth": Image and Reality in the Third Reich (1987)

- Hitler: A Profile in Power (1991)

- Stalinism and Nazism: Dictatorships in Comparison (edited with Moshe Lewin) (1997)

- Hitler 1889–1936: Hubris (1998)

- Hitler 1936–1945: Nemesis (2000)

- Making Friends with Hitler: Lord Londonderry and the British Road to War (2004)

- Death in the Bunker (2005)

- Fateful Choices: Ten Decisions That Changed the World, 1940–1941 (2007)

- Hitler, the Germans and the Final Solution (2008)

- Hitler (a shorter version of his two-volume biography) (2008)

- Luck of the Devil The Story of Operation Valkyrie (2009)

- The End: Hitler's Germany 1944–45 (2011)

- To Hell and Back: Europe, 1914–1949 (2015)

- Roller-Coaster: Europe, 1950–2017 (2018)

- Personality and Power: Builders and Destroyers of Modern Europe (2022)

Images for kids

-

Adolf Hitler, the subject of several of Kershaw's books.

See also

In Spanish: Ian Kershaw para niños

In Spanish: Ian Kershaw para niños

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |