Expedition of the Thousand facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Expedition of the Thousand |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the wars of Italian unification | |||||||||

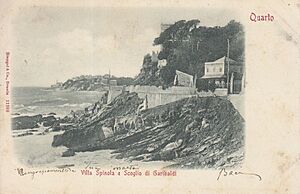

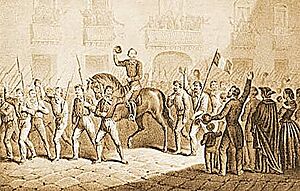

The beginning of the expedition at Quarto al Mare, Genoa |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Supported by: |

Supported by: |

||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

90,000 | ||||||||

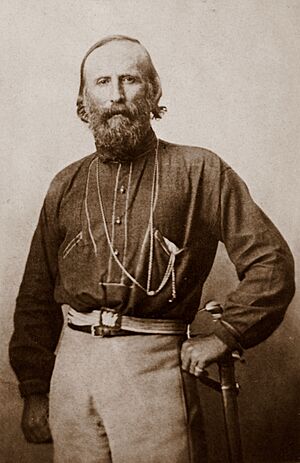

The Expedition of the Thousand (Italian: Spedizione dei Mille) was a key event in the Unification of Italy in 1860. A group of volunteers, led by the famous general Giuseppe Garibaldi, sailed from Quarto al Mare near Genoa. Their goal was to conquer the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, which was a large kingdom in southern Italy ruled by the Spanish House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies. The expedition got its name because it started with about 1,000 participants.

Garibaldi's volunteers, joined by many people from southern Italy, grew into a larger force called the Southern Army. In just a few months, they won several battles against the Bourbon army. They managed to conquer the entire Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. This expedition was a huge success. It ended with a special vote (a plebiscite) that brought Naples and Sicily into the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia. This was the last major step before the Proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy on March 17, 1861.

The Expedition of the Thousand was a rare moment when four important leaders of Italian unification agreed on a plan. These were Giuseppe Mazzini, Giuseppe Garibaldi, King Victor Emmanuel II, and Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour. They all had different goals. Mazzini wanted to free Southern Italy and Rome to create a republic. Garibaldi aimed to conquer the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies for King Victor Emmanuel II and then move on to Rome. Cavour, the Prime Minister of Piedmont-Sardinia, wanted to avoid taking Rome to prevent conflict with France, who protected the Papal States.

This project was very ambitious and risky. One thousand men were trying to conquer a kingdom with a much larger army and navy. People joined for various reasons: Garibaldi wanted a united Italy. The wealthy people in Sicily wanted an independent Sicily as part of Italy. Common people hoped for land and an end to harsh rule. Francesco Crispi, a key figure in unification, helped start the expedition.

Some historians believe the British Empire supported the expedition. They say Britain wanted a friendly government in Southern Italy because the Suez Canal was about to open, making the region strategically important. The Bourbons were seen as unreliable because they were getting closer to Russia. However, there is no strong proof of this. The Royal Navy only protected British interests during the landing. British donors did support the expedition financially. French and Spanish ships actually supported the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies during the Siege of Gaeta.

Contents

- Why the Expedition Happened

- The Expedition Begins

- Setting Sail

- Landing in Sicily

- Calatafimi and Palermo Battles

- Public Support for the Expedition

- Garibaldi's Government in Sicily

- More Troops Arrive

- Bourbon Retreat from Sicily

- Sicily Fully Conquered

- Crossing to Mainland Italy

- Advance to Naples

- Bourbon Resistance in the North

- The Final Stages

- Garibaldi Leaves Naples

- The Italian Flag

- Maps of the Expedition

- What Happened Next

- Historical Views

- Movies About the Expedition

- See also

Why the Expedition Happened

Italy's Political Situation

For a long time, the Italian peninsula was divided into many small states. After the French Revolution, people started wanting to unite Italy into one country. The Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia became a leader in this movement.

The Expedition was part of the larger process of Italian unification. This was largely planned by Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, the Prime Minister of Piedmont-Sardinia. The Second Italian War of Independence ended in 1859. This war gave Lombardy to Piedmont-Sardinia, but Venice remained under Austrian control. Many Italian patriots were unhappy about this.

By March 1860, several regions like Tuscany, Emilia-Romagna, Modena, and Parma had already joined Piedmont-Sardinia. Patriots then looked to the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies as the next step. This kingdom included all of southern mainland Italy and Sicily.

Other European countries had different interests. The United Kingdom supported Piedmont-Sardinia to limit French influence in Italy. France wanted more control over the Mediterranean Sea. Other powerful countries like Spain, Austria, and Russia supported the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies but mostly waited to see what would happen. This left the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies quite isolated.

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was led by a young and inexperienced king, Francis II of the Two Sicilies. He had only become king in May 1859. The kingdom had also upset the United Kingdom in the past and refused to join the Crimean War. This made them diplomatically isolated.

Garibaldi, though a republican, had secretly been in touch with King Victor Emmanuel II to plan the expedition. He agreed to work with the royal family until Italy was united. Even Giuseppe Mazzini, a strong republican, said, "It is no longer a question of republic or monarchy: it is a question of national unity."

Sicilian Desire for Independence

In 1860, the only strong group against the Bourbons in southern Italy was the Sicilian independence movement. The memory of the harsh Sicilian revolution of 1848 was still fresh. Many leaders of that revolution, like Rosolino Pilo and Francesco Crispi, had fled to Turin. They believed Garibaldi's intervention in Sicily, supported by Piedmont, was key to unification.

In March, Rosolino Pilo asked Garibaldi to lead an expedition. Garibaldi was hesitant at first. He wanted to lead a revolution only if the people truly wanted it and if it was done in the name of King Victor Emmanuel II. He wanted to avoid past failures.

Even without Garibaldi's immediate support, Rosolino Pilo went to Sicily in March. He prepared the ground for the expedition, getting support from landowners. These landowners later provided their armed groups, called picciotti, to help Garibaldi. Rosolino Pilo was killed in a fight in May 1860.

Situation in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies had faced many revolts in the early 1800s, all put down by the Bourbons. Their army was well-funded and included loyal foreign soldiers, especially Swiss.

However, the kingdom was isolated diplomatically. King Francis II was young and inexperienced. This made the kingdom vulnerable.

The Gancia Revolt

A revolt started in Palermo on April 4. It was quickly put down, but it sparked other uprisings. Rosolino Pilo led a march from Messina, telling people to be ready for Garibaldi.

News of the revolt reached Garibaldi, but it was not very encouraging. He almost gave up on the expedition. However, Francesco Crispi convinced him with a new, possibly false, version of the news, which made Garibaldi decide to go ahead.

Cavour's Role

Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour thought the expedition was risky. He worried it would harm relations with France, especially if Garibaldi aimed for Rome. But Cavour also saw Garibaldi as an "opportunity." He hoped Garibaldi's actions would cause an uprising in the Two Sicilies, forcing Piedmont-Sardinia to step in.

Cavour decided to wait and see. He only openly supported the expedition when it seemed likely to succeed. He sent warships to Sicily to observe the situation. He also had Giuseppe La Farina keep in close contact with Garibaldi. Cavour and King Victor Emmanuel II agreed that the government would cautiously help Garibaldi.

Finding a Reason to Fight

Piedmont-Sardinia needed a good reason (a casus belli) to attack the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. They never officially declared war. Cavour wanted to appear as someone who maintained order among European powers. The only way to justify intervention was an internal uprising. This would show that the people were unhappy with the Bourbon king, Francis II of the Two Sicilies.

Sicily was a good place for such an uprising. Meanwhile, Garibaldi was busy gathering volunteers. He had already shown his skill as a military leader in previous campaigns, leading volunteers against regular armies.

The Expedition Begins

Setting Sail

In March 1860, Rosolino Pilo urged Giuseppe Garibaldi to lead an expedition to free southern Italy. Garibaldi eventually agreed. The expedition was openly preparing across Italy. By May 1860, Garibaldi had gathered 1,089 volunteers for his trip to Sicily.

Most volunteers came from Lombardy and Venetia (parts of Austria at the time). Others came from Genoa, Tuscany, Sicily, and Naples. There were also 33 foreign volunteers. Most volunteers were students and skilled workers from middle-class families.

The 1,089 volunteers were armed with old muskets. They wore red shirts and grey trousers, which earned them the name Redshirts. The Redshirts became very famous and inspired armies worldwide.

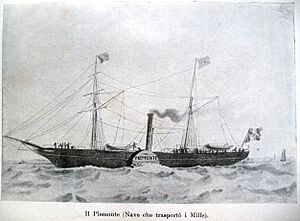

On the night of May 5, a small group of Redshirts, led by Nino Bixio, "took" two steamships from the Rubattino shipping company in Genoa. (The ships were actually provided by Rubattino through a secret deal with Piedmont-Sardinia). The ships were named Il Piemonte and Il Lombardo. That night, the expedition set sail for Sicily from a rock now called the Scoglio dei Mille, at Quarto al Mare. This rock was near Villa Spinola, where Garibaldi had his headquarters.

Before leaving, Garibaldi again promised his loyalty to Victor Emmanuel II. He said his goal was to conquer Sicily for the king. There was likely a lot of secret cooperation between Cavour, Victor Emmanuel, and Garibaldi. After Garibaldi landed, Admiral Persano was ordered to support the expedition.

On May 7, Garibaldi stopped at Talamone on the Tuscan coast to get ammunition and three old cannons. He made another stop on May 9 near Porto Santo Stefano for coal. He got these supplies as a major general of the royal army.

The two steamers took an unusual route to avoid Bourbon ships, going close to the Tunisian coast. They eventually headed for Marsala because they learned its port was not protected by Bourbon vessels. The Thousand arrived in Marsala on the afternoon of May 11, 1860.

The army of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was large, with about 90,000 active soldiers and 50,000 in reserve.

Landing in Sicily

Garibaldi's landing in Marsala on May 11, 1860, was helped by several things. Two British Royal Navy warships, HMS Argus and HMS Intrepid, were in the port. Their presence discouraged Bourbon ships from attacking. The Lombardo was sunk only after everyone had disembarked, and the Piemonte was captured.

Also, the Bourbon commanders had sent troops away from Marsala just one day before the landing. This left the area less defended. Francesco Crispi and others had arrived earlier to get local support for the volunteers.

Historian George Macaulay Trevelyan stated that the British ships did not actively help Garibaldi. Their boilers were off, and their commanders were on land. The British navy remained neutral. Garibaldi later asked for gunpowder from them during the Battle of Palermo, but they refused. On May 12, 200 Sicilian volunteers joined Garibaldi. His forces grew even more with later landings of Sardinian troops and freed prisoners.

Calatafimi and Palermo Battles

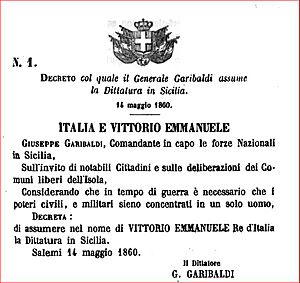

On May 12, Garibaldi left Marsala and moved quickly into Sicily. Many Sicilian volunteers, including Franciscan priests, joined him. These volunteers formed a new group called the Hunters of Etna. On May 14, in Salemi, Garibaldi declared himself Dictator of Sicily in the name of King Victor Emmanuel II.

The Thousand, with 500 Sicilian rebels, fought their first major battle on May 15, 1860, at Calatafimi. They faced about 3,000 Two Sicilies soldiers. News of Garibaldi's victory spread fast, encouraging more Sicilians to revolt. In towns like Alcamo and Partinico, locals attacked retreating Bourbon soldiers. This battle greatly boosted the morale of Garibaldi's forces. It also discouraged the Bourbons, who felt abandoned and were poorly led. Garibaldi promised land to men who volunteered, which helped his army grow to 1,200 local fighters.

After Calatafimi, Garibaldi headed for Palermo. Along the way, 3,200 more Sicilians joined him, bringing his total force to 4,000 men. On May 27, Garibaldi and the volunteers reached Palermo. They prepared to enter the city, fighting hard battles at the Admiral's Bridge and Porto Termini.

With help from a Palermo uprising, Garibaldi's forces and the rebels conquered the city between May 28 and 30. This happened despite heavy bombing from Bourbon ships. On May 30, the Bourbons, trapped in their forts, asked for a ceasefire. This truce lasted until June 3. On June 6, the Bourbon troops defending Palermo surrendered. Garibaldi allowed them to leave the city with military honors. The garrison left on July 7, after King Francis II of the Two Sicilies approved their withdrawal.

Public Support for the Expedition

On June 21, 1860, Giuseppe Garibaldi fully occupied Palermo. This news spread worldwide, and public opinion supported the expedition. Workers in Glasgow and Liverpool offered their wages to help. A French newspaper, Le Siècle, asked for donations and volunteers. Alexandre Dumas, a French writer, arrived in Palermo to supply Garibaldi with weapons and promote the expedition through newspapers.

Famous writers like George Sand and Victor Hugo also supported Garibaldi. Even Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels called the conquest of Palermo "one of the most surprising military feats of our century." Money and volunteers came from all over Europe, the United States, Uruguay, and Chile. Many joined, including 33 Englishmen.

This widespread support was mainly due to the great respect people had for Garibaldi. Meanwhile, conservative governments like Austria, Russia, Prussia, and Spain protested against Piedmont-Sardinia.

Garibaldi's Government in Sicily

On July 7, Giuseppe Garibaldi declared himself Dictator of Sicily. He did this "in the name of Victor Emmanuel, King of Italy." Garibaldi then sent his generals to advance on other Sicilian cities like Messina, Catania, and Syracuse. King Francis II of the Two Sicilies strengthened his garrisons in Messina and Syracuse.

Garibaldi also set up a government in Palermo with six ministries. He appointed representatives to London, Paris, and Turin. He also signed a decree to provide pensions for widows and help for orphans of those killed fighting for Italy.

More Troops Arrive

Throughout June, more Sicilian volunteers and others from Italy joined Garibaldi. These new forces became part of the Southern Army. On July 5 and 7, over 2,000 volunteers landed in Palermo. On July 22, about 1,535 more volunteers arrived.

Over 20 naval expeditions brought about 21,000 more volunteers to Sicily, in addition to the first 1,000. By late August 1860, Cavour stopped these departures from northern ports. He planned to invade the Papal States and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies himself.

Bourbon Retreat from Sicily

The Bourbon troops were ordered to retreat east and leave Sicily. An uprising in Catania on May 31 was crushed by local Bourbon forces. However, the order to leave for Messina meant this victory had no lasting effect.

Catania suffered from 15 days of siege. On June 3, royal troops left Catania by land for Messina. They were escorted by warships carrying supplies. In Acireale, after the Bourbons left, angry locals attacked their supporters. The situation was soon calmed by influential citizens.

At this point, only Syracuse, Augusta, Milazzo, and Messina remained under royal control in Sicily. Garibaldi tried to raise more troops, but only gathered about 20,000. Peasants, hoping for land reform, revolted in some areas. At Bronte, on August 4, Garibaldi's friend Nino Bixio brutally put down one of these revolts.

Garibaldi's rapid victories worried Cavour. In early July, Cavour proposed that Sicily immediately join Piedmont. Garibaldi strongly refused, wanting to finish the war first. Cavour's envoy was even arrested. Cavour replaced him with Agostino Depretis, who gained Garibaldi's trust and was named pro-dictator.

On June 25, 1860, King Francis II of the Two Sicilies brought back the constitution that had been in place from 1848 to 1849. This late attempt to gain support failed. It did not convince his moderate subjects to defend his rule. Liberals and revolutionaries were eager to welcome Garibaldi.

Sicily Fully Conquered

On July 20, Giuseppe Garibaldi attacked Milazzo with 4,000 men. They fought against 4,500 Bourbon soldiers. On August 1, the Bourbon commander surrendered with honors. He was taken by ship to Real Cittadella, which was soon under siege. Garibaldi arrived in Milazzo by ship.

Garibaldi's men, led by Giacomo Medici, reached Messina on July 27. Many Bourbon troops had already left. The next day, Garibaldi arrived. An agreement was signed for the Bourbons to leave Messina without causing damage. They were allowed to sail to Naples.

With Messina conquered, Garibaldi prepared to cross the Straits of Messina. He appointed Agostino Depretis to govern Sicily. Meanwhile, there were plans to stop Garibaldi, including attempts on his life, but none succeeded. On August 1, the Bourbon forts of Syracuse and Augusta also surrendered. This completed the conquest of Sicily.

Crossing to Mainland Italy

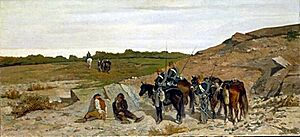

Giuseppe Garibaldi had sent agents to Calabria and Basilicata to prepare for uprisings. On August 19, Garibaldi's men landed in Calabria. Cavour had urged him not to cross the Straits of Messina, but Garibaldi disobeyed, with the silent approval of King Victor Emmanuel II. Garibaldi landed on the beach of Melito di Porto Salvo with 3,700 men.

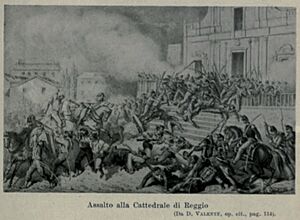

Garibaldi now had almost 20,000 soldiers, thanks to local volunteers joining his Red Shirts. The Bourbons had 80,000. Despite this, Garibaldi met little resistance. Except for some fighting in Reggio Calabria, which Nino Bixio captured on August 21, many Bourbon units simply broke up or joined Garibaldi. On August 30, a Bourbon army surrendered without a fight in Soveria Mannelli. The Bourbon navy also acted similarly.

Advance to Naples

On September 2, Giuseppe Garibaldi and his men entered Basilicata, the first mainland region to rise against the Bourbons. His journey through Lucania was smooth. On September 6, Garibaldi met Giacinto Albini and appointed him Governor of Basilicata. That night, he slept in Eboli and then headed with his troops towards Naples, the capital of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

Bourbon Resistance in the North

In the northern part of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, some peasants loyal to the Bourbons rose up. In Irpinia, Bourbon generals provoked an anti-liberal uprising. Peasants carried out robberies and massacres against liberals.

To stop these riots, 1,500 Garibaldians were sent. Despite being outnumbered, the Bourbon soldiers offered no resistance. Arrests were made, and some ringleaders were punished. Later, in Abruzzo and Molise, the Sardinian army had to use harsher methods against those who resisted the new political structure.

Other violent events happened in Isernia in Molise. Farmers, encouraged by the bishop and Bourbon loyalists, looted and massacred for a week. These acts of resistance against the liberals continued and were often very bloody.

The Final Stages

King Francis II of the Two Sicilies no longer trusted his ministers or soldiers. On September 6, he fled Naples for the fortress city of Gaeta, moving his army to the Volturno river. So, on September 7, Garibaldi entered Naples with his army. He was welcomed as a liberator and took control of the entire Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. The Bourbon troops in the city's castles surrendered quickly.

After Garibaldi took Naples, the southern regions (Sicily, Calabria, Basilicata, and most of Campania) were under his control. Lombardy, Emilia-Romagna, and Tuscany had already joined Piedmont-Sardinia. However, the Papal State still separated the North and South. King Victor Emmanuel II decided to send his army to annex Marche and Umbria, which were part of the Papal State. This would connect northern and southern Italy.

On September 11, Cavour ordered the invasion of the Papal States. The Papal Army was defeated at the Battle of Castelfidardo on September 18. The Piedmontese army occupied most of Umbria and Marche.

Garibaldi wanted to end the Bourbon monarchy for good. In late September and early October, the decisive Battle of the Volturno took place. About 50,000 Bourbon soldiers lost to Garibaldi's men, who were about half their size. Garibaldi barely won this battle. His Southern Army then besieged Capua. Piedmontese forces marched on Gaeta, where King Francis II had taken refuge.

A few days later, on October 21, a special vote (a plebiscite) confirmed that the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies would join the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia. The vote was overwhelmingly in favor.

| Territory | Number of inhabitants | Voters | In favor of annexation | Against annexation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kingdom of Naples | 6,500,000 | 1,650,000 | 1,302,064 | 10,302 |

| Kingdom of Sicily | 2,232,000 | 575,000 | 432,053 | 667 |

The expedition officially ended with a meeting between Victor Emmanuel II and Giuseppe Garibaldi at Teano on October 26, 1860. This meeting is very important in Italian history. It showed that the House of Savoy (Victor Emmanuel's family) now ruled over the former Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and all of Italy.

However, the fighting wasn't completely over. Francis II of the Two Sicilies and the remaining Bourbon army held out in Gaeta. The siege of Gaeta began, first by Garibaldi's forces, then by the Sardinian army. It ended on February 13, 1861, with the Bourbon defeat. Many Bourbon soldiers fled to the Papal State, where they were disarmed. With Francis II's surrender, the last Bourbons of the Two Sicilies went into exile in Rome.

Garibaldi Leaves Naples

On November 9, 1860, at 4:00 am, Giuseppe Garibaldi left Naples on a rowing boat to board the ship Washington. Six months and three days had passed since he began the Expedition of the Thousand.

Garibaldi returned to Caprera, an island, after achieving a difficult feat. The king asked him to stay, but Garibaldi said he would leave for now. He promised to return if the country and king needed him. He later explained that he was tired of the excessive praise from people who had quickly changed their loyalty from Bourbons to Garibaldi supporters.

The Italian Flag

The Italian tricolour (green, white, and red) became a very important symbol of Italian unification. It was also a symbol of the revolutions of 1848. In 1848, King Charles Albert of Piedmont-Sardinia used a tricolour flag with the Savoy family's coat of arms. After the revolutions failed, most old flags were restored. Only the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia kept the Italian tricolour as its national flag.

The Italian tricolour was unofficially used by Garibaldi's volunteers during the Expedition of the Thousand. Garibaldi deeply respected the flag. After losing Sicily, King Francis II of the Two Sicilies tried to limit the damage. On June 25, 1860, he decreed that the green, white, and red flag would also be the official flag of his kingdom, with the Bourbon coat of arms.

This flag was used until March 17, 1861, when the Two Sicilies became part of the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia. Ironically, during the final part of the expedition, the tricolour of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies flew against the tricolour of Piedmont-Sardinia. Two original tricolour flags from Garibaldi's ships are now kept in museums in Rome and Palermo.

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies had used the Italian tricolour once before, during the 1848 revolutions. The Provisional Government of Sicily also adopted the tricolour with a triskelion symbol. But after the uprisings, the old flags were restored.

Maps of the Expedition

What Happened Next

Italy Becomes a Kingdom

Based on the votes (plebiscites) of October 1860, and after the surrender of the fortresses of Gaeta and Messina, the Kingdom of unified Italy was proclaimed on March 17, 1861. This included the southern regions. On November 7, King Victor Emmanuel II entered Naples. In the same month, Marche and Umbria also voted to join the new Kingdom of Italy.

With the Italian peninsula now united, Victor Emmanuel II was declared King of Italy by the new Italian parliament in Turin. The new Kingdom of Italy kept the laws and constitution (Statuto Albertino) of the former Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia. This constitution was now extended to all parts of the new kingdom.

Italy celebrates its unification anniversary every 50 years on March 17. This day is considered important for national identity. November 4, National Unity and Armed Forces Day, celebrates the end of World War I, which is seen as completing Italy's unification.

Extending Piedmont-Sardinia's laws to all new territories caused some problems. People who wanted more local control, especially in the former Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, were unhappy. This was because their traditions were different, and northern administrators struggled to understand them.

A famous saying, "Once Italy is made, Italians must be made," highlights the challenge of uniting the people. There were deep differences between Italian regions. Many Italians, especially from the south, later decided to emigrate to places like the Americas and Australia due to difficulties in the new unified state.

Diplomatic Reactions

Other European countries were not happy about the Sardinian army's direct involvement in the Expedition of the Thousand. Spain and the Russian Empire broke off diplomatic relations with Piedmont-Sardinia. The Austrian Empire sent troops to its border. France did not make hostile statements but recalled its ambassador. Queen Victoria and her prime minister convinced Prussia not to interfere with Italy's unification.

After the Kingdom of Italy was created, the United Kingdom and Swiss Confederation were the first to recognize the new state (March 30, 1861). The United States followed on April 13. France recognized Italy on June 15. Portugal, Greece, the Ottoman Empire, and Scandinavian countries also recognized it.

What Happened to the Fighters

It was important to include the Bourbon army into the new Italian army to build a national identity. It was also needed to strengthen the army for a possible war against Austria.

Officers and soldiers from the old Bourbon army were forced to join the new Italian army and navy. Those who refused to swear loyalty to the new king and stayed loyal to Francis II of the Two Sicilies were sent to prison camps. However, recent studies show that the number of prisoners and deaths in these camps was much lower than some older stories claimed.

Some soldiers hid and continued to fight for the independence of the Two Sicilies by joining groups called brigands. Unlike Bourbon officers, most of Garibaldi's officers were not recognized with high ranks in the new Italian army. However, some, like Nino Bixio, played important roles. Some who joined Garibaldi, like Carmine Crocco, were so disappointed that they later became brigands.

Disappointment After Unification

After unification, many hopes from the Expedition of the Thousand were not met, especially in Sicily. Farmers and poor people had believed that Giuseppe Garibaldi would improve their lives. Instead, they faced higher taxes and forced military service.

Many liberals in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies who supported unification were also disappointed. They felt the political situation did not change much. The clergy were unhappy because the Papal State lost land, and church properties were taken.

Historical Views

The Expedition of the Thousand is a very famous event in Italian history. However, some historians believe it led to problems like the brigandage (local resistance), the economic differences between northern and southern Italy, and increased emigration from the South.

Some historians argue that traditional accounts of the expedition are too heroic. They point to the harsh way the new Kingdom of Italy dealt with brigandage. This was almost like a civil war, requiring many soldiers and leading to violence against civilians. This anti-Savoy brigandage happened mostly in Southern Italy.

However, other historians, like Francesco Saverio Nitti, say that brigandage was common in the South even before unification. Also, the idea that the South was hostile to the new kingdom is questioned by the fact that in the 1946 referendum, the South largely voted to keep the monarchy, while the North voted for a republic.

Some interpretations suggest that Garibaldi's victories were due to Bourbon officers being bribed. But it is more likely that Bourbon generals were divided by rivalries and did not want to risk their lives for a king they did not love or fear. Even a pro-Bourbon historian described the poor state of the Bourbon army at the time.

Movies About the Expedition

- 1860 by Alessandro Blasetti (1934)

- A Garibaldian in the Convent by AVittorio De Sica (1942)

- Senso by Luchino Visconti (1954)

- Garibaldi by Roberto Rossellini (1960)

- The Leopard by Luchino Visconti (1963)

- Bronte: cronaca di un massacro che i libri di storia non hanno raccontato by Florestano Vancini (1972)

- Li chiamarono... briganti! by Pasquale Squitieri (1999)

- We Believed by Mario Martone (2010)

See also

- Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

- Post-Unification Italian Brigandage

- Proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy

- Southern Italy

- Timeline of the unification of Italy

- Unification of Italy