Agostino Depretis facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Agostino Depretis

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Prime Minister of Italy | |

| In office 29 May 1881 – 29 July 1887 |

|

| Monarch | Umberto I |

| Preceded by | Benedetto Cairoli |

| Succeeded by | Francesco Crispi |

| In office 19 December 1878 – 14 July 1879 |

|

| Monarch | Umberto I |

| Preceded by | Benedetto Cairoli |

| Succeeded by | Benedetto Cairoli |

| In office 25 March 1876 – 24 March 1878 |

|

| Monarch | Victor Emmanuel II Umberto I |

| Preceded by | Marco Minghetti |

| Succeeded by | Benedetto Cairoli |

| Minister of the Interior | |

| In office 25 November 1879 – 29 July 1887 |

|

| Prime Minister | Benedetto Cairoli Himself |

| Preceded by | Tommaso Villa |

| Succeeded by | Francesco Crispi |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 4 April 1886 – 29 July 1886 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Carlo Felice Nicolis |

| Succeeded by | Francesco Crispi |

| In office 29 June 1885 – 6 October 1885 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Pasquale Stanislao Mancini |

| Succeeded by | Carlo Felice Nicolis |

| In office 19 December 1878 – 14 July 1879 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Benedetto Cairoli |

| Succeeded by | Benedetto Cairoli |

| In office 26 December 1877 – 24 March 1878 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Luigi Amedeo Melegari |

| Succeeded by | Luigi Corti |

| Minister of Finance | |

| In office 25 March 1876 – 26 December 1877 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Girolamo Cantelli |

| Succeeded by | Agostino Magliani |

| In office 17 February 1867 – 10 April 1867 |

|

| Prime Minister | Bettino Ricasoli |

| Preceded by | Antonio Scialoja |

| Succeeded by | Francesco Ferrara |

| Minister of the Navy | |

| In office 20 June 1866 – 17 February 1867 |

|

| Prime Minister | Bettino Ricasoli |

| Preceded by | Diego Angioletti |

| Succeeded by | Giuseppe Biancheri |

| Minister of Public Works | |

| In office 3 March 1862 – 8 December 1862 |

|

| Prime Minister | Urbano Rattazzi |

| Preceded by | Ubaldino Peruzzi |

| Succeeded by | Luigi Federico Menabrea |

| Member of the Chamber of Deputies | |

| In office 18 February 1861 – 29 July 1887 |

|

| Constituency | Stradella |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 31 January 1813 Stradella, Lombardy, Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy |

| Died | 29 July 1887 (aged 74) Stradella, Lombardy, Kingdom of Italy |

| Political party | Historical Left |

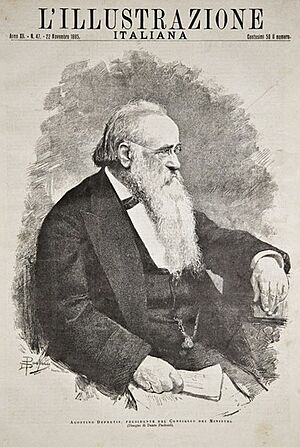

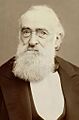

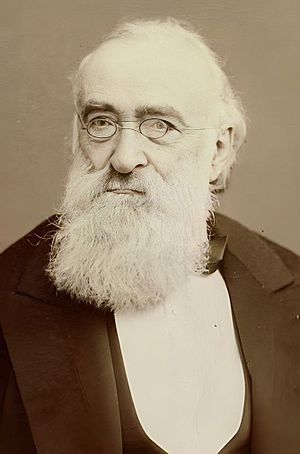

Agostino Depretis (born January 31, 1813 – died July 29, 1887) was an important Italian politician. He served as the Prime Minister of Italy many times between 1876 and 1887. He was also the leader of a political group called the Historical Left for over ten years.

Depretis is known as one of the longest-serving Prime Ministers in Italian history. He was a master of a political style called Trasformismo. This meant creating a flexible government that included different groups, avoiding extreme ideas from either the left or the right side of politics after Italy became a united country.

Contents

Early Life and Italy's Unification

Agostino Depretis was born in Bressana Bottarone, near Stradella. At that time, this area was part of Napoleon's French Empire. After Napoleon's defeat, the Kingdom of Sardinia was restored. Depretis studied law and became a lawyer.

From a young age, he followed the ideas of Giuseppe Mazzini and joined a group called La Giovine Italia (Young Italy). He was involved in secret plans by Mazzini and almost got caught by the Austrians while trying to smuggle weapons into Milan. In 1848, he was elected as a deputy (a member of parliament). He joined the Historical Left political group and started a newspaper called Il Diritto.

Depretis often disagreed with the policies of the Prime Minister of Piedmont, Camillo Benso di Cavour. For example, he voted against Piedmont joining the Crimean War. However, after Lombardy became part of the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1859, Cavour still chose Depretis to be the governor of Brescia.

In 1860, Giuseppe Garibaldi led his famous Expedition of the Thousand to Sicily. This group of volunteers aimed to conquer the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, which was ruled by the Bourbons. It was a very risky plan to take over a kingdom with a much larger army and navy using only a thousand men. But the expedition succeeded! It ended with a vote that brought Naples and Sicily into the Kingdom of Sardinia. This was a big step before the creation of the Kingdom of Italy on March 17, 1861.

Many people had different reasons for joining Garibaldi's expedition. Garibaldi wanted a united Italy. Sicilian business owners wanted an independent Sicily as part of Italy. Farmers hoped for land and an end to unfair treatment.

In 1860, Depretis went to Sicily. His job was to try and bring together Cavour's idea of immediately joining Sicily with the Kingdom of Italy, and Garibaldi's wish to wait until Naples and Rome were also free. Depretis took over from Garibaldi's advisor, Francesco Crispi, as a temporary leader (prodittatore) in Sicily. But he couldn't convince Garibaldi and his friends to join Sicily right away. So, Depretis resigned in September 1860.

Becoming a Government Minister

After Cavour died, King Victor Emmanuel II asked Bettino Ricasoli and then Urbano Rattazzi to form new governments. Rattazzi was a leader of the Left and created a government with members from different political groups. On March 3, 1862, Depretis became the Minister of Public Works. He helped arrange things with Garibaldi.

However, in August 1862, the Royal Italian Army fought against Garibaldi's volunteer army at the Battle of Aspromonte. Garibaldi's men were marching from Sicily towards Rome, hoping to add it to the Kingdom of Italy. In the battle, Garibaldi was wounded and captured. Rattazzi's strong actions against Garibaldi caused many public protests. This forced the Prime Minister to resign in September 1862.

Francesco Crispi also accused Depretis of causing some riots in Sarnico in May 1862 to make Garibaldi look bad. After Rattazzi's government fell, it seemed like Depretis's political career might be over, especially when Crispi became the leader of the Left. Depretis stayed out of the main spotlight for a few years. But he still took part in parliament, speaking about laws for unifying the country and opposing ideas of strong regional power. He was very active during the 1865 election campaign and later became Vice President of the Chamber of Deputies.

In 1866, Italy was preparing for war with the Austrian Empire. After Italy signed an alliance with Prussia, Ricasoli became Prime Minister. He replaced General Alfonso Ferrero La Marmora, who would lead the Italian troops. The king wanted a government that included members from both the Right and the Left.

On June 20, Depretis was appointed Minister of the Navy. On the very same day, the Third Italian War of Independence began. After Italy lost the Battle of Custoza, Depretis urged Admiral Carlo Persano to attack the island of Lissa. This was meant to be revenge for the Custoza defeat. However, Depretis did not give Admiral Persano clear orders about the expedition against the Austrian fleet. The Italian Royal Navy suffered a major defeat. To calm the public anger after these two losses, Depretis called for Admiral Persano to be put on trial. Persano was found guilty of being incompetent in 1867 and removed from duty.

Despite these naval losses, the war ended with Austria being defeated. Austria gave the region of Venetia to Italy. Italy gaining this rich territory was a big step in uniting the country.

On February 17, 1867, Depretis resigned as Minister of the Navy. His time as minister was quite debated. Some people argued that as a civilian with no experience, he couldn't have made big changes to the navy quickly. They also said that because war was about to start, he had to accept the plans made by the ministers before him.

Leader of the Left

On February 17, 1867, Depretis became the Minister of Finance in Ricasoli's second government. However, Ricasoli resigned a few months later, on April 10, and Depretis went back to being a regular member of parliament.

When Rattazzi died in 1873, Depretis became the new leader of the Left. On June 25, 1873, the conservative government led by Giovanni Lanza fell. This happened because Depretis's moderate Left group joined with many members of the Right who no longer supported the Minister of Finance, Quintino Sella. Sella had given up on a plan to increase taxes to balance the national budget. King Victor Emmanuel II then asked the conservative Marco Minghetti to form a new government and suggested he include members from the Left. Minghetti tried to reach an agreement with Depretis, but it didn't work.

Minghetti and Sella had a big plan to balance the budget. They needed strong support in parliament and tried to force independent politicians to choose a side, hoping to create a two-party system like in the United Kingdom. However, in Italy's political system, which was often affected by local interests and corruption, their gamble failed.

The 1874 election did not give Minghetti the strong support he hoped for. Depretis's opposition group received a lot of support, especially in Southern Italy. Minghetti's government survived, but the Left became much stronger. Two years later, members of parliament from Tuscany were unhappy with the government because it didn't help with Florence's financial problems. The government was defeated in a vote about nationalizing railways on March 18, 1876. Minghetti had to resign. As a result, Depretis became Prime Minister, with 414 out of 508 members of parliament supporting his government. This event was called the "parliamentary revolution" by political writers.

Prime Minister of Italy

First Term as Prime Minister

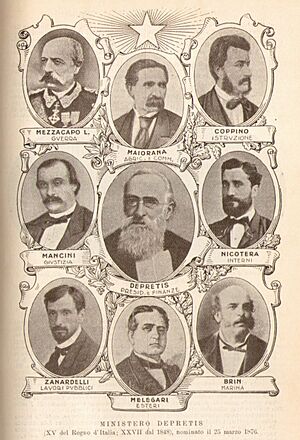

On March 25, 1876, Depretis officially became Prime Minister. His government was the first to be made up only of members from the Left. Important ministers included Giovanni Nicotera, Pasquale Stanislao Mancini, Michele Coppino, Giuseppe Zanardelli, and Benedetto Brin.

To make his position stronger, Depretis called for new elections in November 1876. For the first time, the left-wing party won an election. They received almost 70% of the votes and took 414 out of 508 seats. Unlike previous right-wing governments, which were mostly made up of rich landowners from the north, the left-wing government represented the middle class from the south. They supported lower taxes, keeping government separate from religion, a strong foreign policy, and public jobs.

A major reform proposed by his government was the school law, named after Minister Coppino. This law, presented on July 15, 1877, made primary education compulsory, non-religious, and free for children aged six to nine. Depretis also raised the minimum income for the mobile wealth tax, which helped industrial workers. An important decree on August 25, 1876, set rules for the Prime Minister's office, aiming to limit the king's power and reduce conflicts among ministers.

The foreign policy of his first government was careful, similar to the governments before it. This led to criticism from those who wanted Italy to get closer to the German Empire to oppose France. This anti-French feeling grew in May 1877 when a pro-church government took power in Paris. However, Depretis's government faced strong attacks against the Minister of the Interior Nicotera. Some in the majority accused Nicotera of abuses. Unable to handle the crisis, Depretis decided to resign in December 1877.

The king again asked Depretis to form a new government. This was the king's last political act before he died a few months later. Depretis struggled to stop disagreements within the Left. He was criticized for getting rid of the Ministry of Agriculture, Industry, and Commerce and creating the Ministry of Treasury to better control the state budget. On March 11, 1878, Depretis resigned when his chosen candidate lost the election for President of the Chamber of Deputies. The next government was led by another important leftist, Benedetto Cairoli.

Second Term as Prime Minister

In November 1879, Depretis joined Cairoli's government as Minister of the Interior. Around this time, many people were upset with Cairoli's policies at the Berlin Congress. Italy gained nothing, while Austria-Hungary was allowed to occupy Bosnia and Herzegovina. A few months later, an attempt by Giovanni Passannante to assassinate King Humbert I in Naples on December 12, 1878, led to Cairoli's government falling.

Depretis was then appointed Prime Minister by the king. His government included members from both the Left and the Right. On June 24, 1879, the Italian Senate approved a bill to remove the tax on milling grain, but with big changes. However, on July 3, the Chamber rejected the law and voted against the government. Depretis's third government had to resign after only six months. The next government was again led by Cairoli, starting on July 14.

Third Term as Prime Minister

After France occupied Tunis on May 11, 1881, public anger grew. Cairoli resigned to avoid making bad statements to parliament. The king, after Quintino Sella failed to form a new government, appointed Depretis as Prime Minister once again.

On May 20, 1882, Depretis signed the Triple Alliance. This was a secret military agreement between Italy, Germany, and Austria-Hungary. Its purpose was to stand against the power of France and Russia. Italy sought support against France because it had lost its plans for North Africa to the French. Each member promised to help the others if they were attacked by another major power. The treaty said that Germany and Austria-Hungary would help Italy if France attacked it without Italy causing the attack. In return, Italy would help Germany if France attacked Germany. If there was a war between Austria-Hungary and Russia, Italy promised to stay neutral.

In Italy, 1882 also saw the approval of an important electoral reform. On January 22, parliament approved what Depretis called "the only possible universal suffrage" (the right to vote for more people). All men aged 21 or older who had completed at least two years of elementary school, or who paid an annual tax of at least 19.80 lire, were allowed to vote. The voting age was lowered from 25 to 21, and the tax requirement was lowered from ₤40 to ₤19.80. Men who had three years of primary education didn't have to meet the tax requirement. This meant the number of eligible voters grew from 621,896 in the 1880 elections to 2,017,829. The voting system also changed from single-member areas to areas with two to five seats. Voters had as many votes as there were candidates, except in areas with five seats, where they could only vote for four.

In the 1882 general election, the Left became the largest group in Parliament, winning 289 out of 508 seats. The Right came in second with 147 seats. Depretis was confirmed as Prime Minister by the king.

During his long time in office, Depretis changed his government four times. He removed Giuseppe Zanardelli and Alfredo Baccarini to please the Right. Then he gave important jobs to Cesare Ricotti-Magnani, Robilant, and other conservatives. This completed the political process known as Trasformismo.

Depretis also finished building the railway system and started Italy's colonial policy by taking over Massawa. However, at the same time, he increased indirect taxes, influenced parliamentary parties, and spent too much on public works, which hurt Italy's finances. He believed that giving more people the right to vote would give citizens more dignity and responsibility.

Despite suffering from gout, Depretis remained Prime Minister until his death. He often held government meetings in his home in Rome. He moved to Stradella as his illness got worse, and he died there on July 29, 1887, at 74 years old. After his funeral, he was buried in the cemetery of his hometown. Francesco Crispi took over as leader of the Left and head of the government.

Political Ideas and Impact

Depretis was the creator and main supporter of Trasformismo ("Transformism"). This was a way of forming a flexible, centrist government that kept extreme ideas from both the left and the right out of power. This process began in 1883 when Depretis moved closer to the right and changed his government to include conservatives like Marco Minghetti. Depretis had been thinking about this move for a while. The goal was to create a stable government that would avoid weakening the country by sudden shifts to the left or right. Depretis felt that a secure government could ensure peace in Italy.

During this time, many middle-class politicians were more interested in making deals with each other than in political ideas or principles. Large groups were formed, and members were often bribed to join them. The liberals, who were the main political group, were held together by informal "gentleman's agreements." But these agreements were often about making themselves rich. It seemed that actual governing wasn't happening much. Since only about 2 million men could vote, most of whom were wealthy landowners, these politicians didn't have to worry much about improving the lives of the people they were supposed to represent.

However, trasformismo led to debates that the Italian parliamentary system was weak and failing. It eventually became linked with corruption. People saw it as sacrificing principles and policies for short-term gains. The system of trasformismo was not well-liked and seemed to create a big gap between the "Legal" (parliamentary and political) Italy and the "Real" Italy, where politicians became increasingly isolated. This system brought almost no benefits. Illiteracy remained the same in 1912 as it was before Italy was united. Old-fashioned economic policies, combined with poor health conditions, continued to prevent improvements in the country's rural areas.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Agostino Depretis para niños

In Spanish: Agostino Depretis para niños