Charles Albert of Sardinia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Charles Albert |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

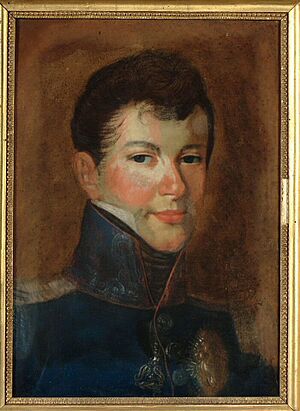

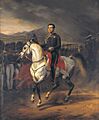

Portrait by Pietro Ayres, c. 1832, wearing the collar of the Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation

|

|||||

| King of Sardinia and Duke of Savoy | |||||

| Reign | 27 April 1831 – 23 March 1849 | ||||

| Coronation | 27 April 1831 | ||||

| Predecessor | Charles Felix | ||||

| Successor | Victor Emmanuel II | ||||

| Prime Ministers |

See list

Cesare Balbo

Gabrio Casati Cesare Alfieri di Sostegno Ettore Perrone di San Martino Vincenzo Gioberti Agostino Chiodo |

||||

| Born | 2 October 1798 Palazzo Carignano, Turin |

||||

| Died | 28 July 1849 (aged 50) Porto, Portugal |

||||

| Burial | 14 October 1849 Royal Basilica, Turin |

||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | Victor Emmanuel II Prince Ferdinando, Duke of Genoa Princess Maria Cristina |

||||

|

|||||

| House | Savoy-Carignano | ||||

| Father | Charles Emmanuel of Savoy | ||||

| Mother | Maria Christina of Saxony | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

Charles Albert (born October 2, 1798 – died July 28, 1849) was the King of Sardinia and ruler of the Savoyard state from 1831 until his death in 1849. He is famous for two main things: creating the first Italian constitution, called the Albertine Statute, and leading the First Italian War of Independence (1848–1849).

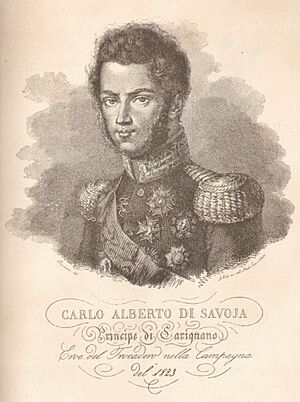

During the time of Napoleon, Charles Albert lived in France. There he received an education that encouraged new, liberal ideas. In 1821, as the Prince of Carignano, he first supported a rebellion. This rebellion wanted to force King Victor Emmanuel I to create a constitutional monarchy, where a king shares power with a parliament. However, Charles Albert soon changed his mind and withdrew his support. He then became more conservative. In 1823, he even joined a military group that fought against liberals in Spain.

He became King of Sardinia in 1831 after his distant cousin, Charles Felix, died without children. At first, Charles Albert was very traditional. He supported other rulers who believed in absolute power. But later, he changed his views again. He started to support the idea of a united Italy, led by the Pope and free from Austrian control. In 1848, he gave his people the Albertine Statute. This was Italy's first constitution and it lasted until 1947.

Charles Albert led his army against the Imperial Austrian army in the First Italian War of Independence. But he lost support from Pope Pius IX and Ferdinand II of the Two Sicilies. His forces were defeated in 1849 at the Battle of Novara. After this defeat, he gave up his throne to his son, Victor Emmanuel II. Charles Albert died in exile a few months later in Porto, Portugal.

His efforts to free northern Italy from Austria were the first steps for the House of Savoy to change the political map of Italy. His son, Victor Emmanuel II, continued these efforts and became the first king of a unified Italy in 1861. People sometimes called Charles Albert "the Italian Hamlet" because he seemed gloomy and unsure. He was also known as "the Hesitant King" because he often struggled to decide between being an absolute ruler or a constitutional one.

Contents

Early Life and Becoming an Heir

Charles Albert was born in Turin, Italy, on October 2, 1798. His parents were Charles Emmanuel, Prince of Carignano and Maria Cristina of Saxony. His family, the House of Savoy-Carignano, was a branch of the main House of Savoy.

At birth, Charles Albert was not expected to become king. The reigning king, Charles Emmanuel IV, had no children. The throne was expected to pass to his brother, Victor Emmanuel I, and then to Victor Emmanuel's young son, Charles Emmanuel. After them, two more brothers of Charles Emmanuel IV were in line. However, in 1799, both young Charles Emmanuel and one of the king's brothers died. This meant Charles Albert's chances of becoming king suddenly became much higher.

Growing Up During the Napoleonic Era

Charles Albert's father had studied in France and supported liberal ideas. In 1796, when the French army invaded Italy, his parents sided with the French. They were later sent to Paris and lived in difficult conditions. This is where Charles Albert and his sister, Maria Elisabeth, grew up.

In 1800, Charles Albert's father died. His mother had to deal with the French, who didn't recognize her family's titles or property. She refused to send Charles Albert to his family in Sardinia for a more traditional education.

When Charles Albert was twelve, he and his mother met Napoleon. Napoleon gave Charles Albert the title of count and some money each year. Charles Albert then went to school in Paris. He also spent time in Geneva with his mother. In 1814, at age sixteen, he joined a military school in France. Napoleon even made him a lieutenant in the French army.

Returning to Turin and Marriage

After Napoleon's final defeat, Charles Albert returned to Turin in May 1814. He was welcomed by King Victor Emmanuel I and his wife, Queen Maria Theresa. Charles Albert's family property was given back to him. He was also given the Palazzo Carignano as his home. Since King Victor Emmanuel I and his brother had no male children, Charles Albert was now the likely heir to the throne.

Because of his liberal education in France, the court assigned him mentors. They wanted to teach him more conservative ideas. However, these mentors didn't really change Charles Albert's way of thinking.

Marriage and Family Life

The court decided that marriage might help Charles Albert find balance. He agreed to marry sixteen-year-old Archduchess Maria Theresa. She was the daughter of Ferdinand III, Grand Duke of Tuscany. They married on September 30, 1817, in Florence Cathedral.

Maria Theresa was very shy and religious, quite different from Charles Albert. They lived in the Palazzo Carignano. Charles Albert invited young thinkers with liberal ideas to his home. Among his close friends were Cesare Balbo and Massimo d'Azeglio.

Charles Albert and Maria Theresa had two miscarriages. But on March 14, 1820, they had a son, Victor Emmanuel II, who would later become the first King of Italy.

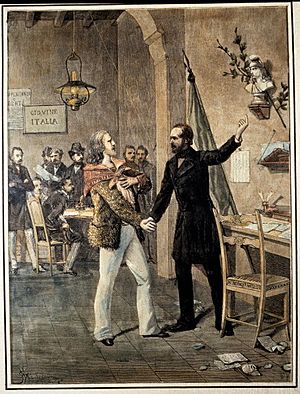

The Revolution of 1821

In 1820, a rebellion in Spain forced their king to accept a constitution. This inspired many in Europe to seek similar changes. Rebellions broke out in Naples and Palermo. In March 1821, young liberals met with Charles Albert. They saw him as someone who could help the House of Savoy move away from absolute rule.

These plotters did not want to get rid of the Savoy family. Instead, they wanted to force the king to make reforms. Charles Albert had promised to support them. On March 6, he confirmed he would support their plan. They wanted to gather troops, surround King Victor Emmanuel I's home, and demand a constitution. Charles Albert was supposed to be the go-between for the plotters and the king.

However, the next morning, Charles Albert changed his mind. He told the Minister of War about the plot. There was an attempt to stop the conspiracy, but it continued to grow. On March 10, Charles Albert, full of regret, went to the king and asked for forgiveness. That night, rebels took control of the city of Alessandria. The revolutionaries decided to act, even without Charles Albert's full support.

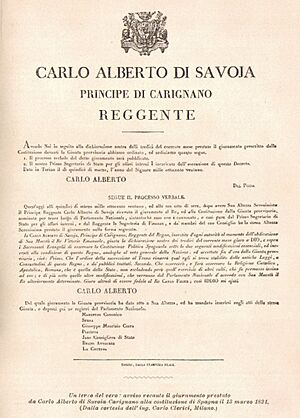

Regent and the Spanish Constitution

On March 11, 1821, King Victor Emmanuel I held a meeting. Charles Albert was there and agreed that a constitution should be granted. But rumors spread that Austrian and Russian forces might intervene to restore order. The king decided to wait. The next day, rebels took over the Citadel of Turin. Victor Emmanuel I then asked Charles Albert to talk with the rebels.

That evening, as the uprising spread, the king gave up his throne. He handed power to his brother, Charles Felix. Since Charles Felix was away, Charles Albert was named regent. He was only 23 years old.

Charles Albert found himself in charge of a big crisis he had helped create. He had to form a new government. He tried to talk with the rebels, but it didn't work. Fearing public anger, on March 13, 1821, Charles Albert announced that he would grant the Spanish Constitution. He said this was pending the new king's approval.

On March 15, Charles Albert swore to follow the Spanish Constitution. Meanwhile, liberals from Lombardy arrived. They asked Charles Albert to declare war on Austria to free Milan. But he refused. Charles Felix, the new king, was very angry about his brother giving up the throne. He ordered Charles Albert to come to Novara. He also declared that all actions taken by Charles Albert as regent, including the constitution, were invalid.

A Conservative Period (1821–1831)

On March 21, 1821, Charles Albert secretly left Turin. He went to Novara, which was still loyal to the king. He stayed there for six days. On March 29, Charles Felix ordered him to go to Tuscany.

Life in Florence

Charles Albert arrived in Florence on April 2, 1821. His wife and son joined him later. His father-in-law, Grand Duke Ferdinand III, gave them a place to live. In May, Charles Felix met with Victor Emmanuel I. They decided that Charles Albert was responsible for the conspiracy.

Because of this, Charles Albert decided to give up his liberal ideas. Charles Felix had even thought about removing Charles Albert from the line of succession. He wanted to pass the crown directly to Charles Albert's son, Victor Emmanuel. But Metternich, an important Austrian statesman, was against this idea.

In Florence, Charles Albert became interested in culture. He collected old books and read modern authors. On November 15, 1822, his second son, Ferdinand, was born.

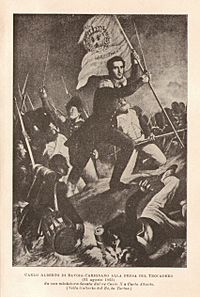

Joining the Spanish Expedition

In 1823, a French army was sent to Spain. Their job was to stop a liberal revolution and put King Ferdinand VII back on his throne. Charles Albert wanted to show he was sorry for his past actions. He asked to join this army. He finally received permission on April 26.

Charles Albert sailed to Marseilles and then traveled to Spain. He joined a French division. He showed great courage in a fight with the enemy. The French made him a member of the Legion of Honour. He continued south towards Cadiz, where the Spanish government was hiding.

In August 1823, the French attacked the fortress of Trocadero. This was the last place the Spanish government held. Charles Albert fought bravely at the front of the troops. He jumped into the water, holding a flag, and entered the enemy trenches. He tried to stop prisoners from being killed. The French soldiers gave him an officer's epaulettes to honor his bravery.

He was among the first to enter Trocadero. King Ferdinand VII and his queen were freed and thanked him. On September 2, Charles Albert received another honor, the Cross of the Order of Saint Louis.

Return to Turin

After the expedition, Charles Albert went to Paris. He attended many parties and met important people. King Charles Felix of Sardinia decided it was time for Charles Albert to return to Turin. But first, Charles Albert had to promise to respect all the old laws of the monarchy when he became king. On February 6, 1824, he arrived back in Turin. He entered the city at night to avoid any protests.

Once back in Turin, Charles Albert mostly lived at Racconigi Castle. He began preparing to rule. He studied economics and visited Sardinia to understand the island's conditions. He was also a writer. He wrote fairy tales for his children, comedies, and historical notes. He later regretted these writings and had them removed from circulation.

Even though the times were conservative, Charles Albert supported some liberal writers. He also owned books by thinkers like Adam Smith, who supported new economic ideas.

Becoming King

In 1830, King Charles Felix became very ill. He called Charles Albert to his bedside on April 24, 1831. With the government present, the king said, "Behold my heir and successor, I am sure that he will act for the good of his subjects."

Charles Felix died on April 27, 1831. Charles Albert then became king. He met with court officials and brought his sons to the Royal Palace. The troops swore loyalty to the new king. This marked the end of the direct line of the House of Savoy and the beginning of the Carignano branch on the throne.

King Charles Albert: Early Years (1831–1845)

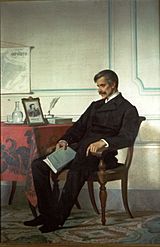

Charles Albert became king at age 33. He was not in good health and suffered from a liver disease. He was also very religious. He worked long hours every day.

Relations with France and Austria

The new king was worried by the July Revolution in France, which had removed King Charles X. This led him to make an alliance with the Austrian Empire. In 1831, he signed a treaty that put the Kingdom of Sardinia under Austria's protection. Charles Albert even said he would be happy to serve in the Austrian army if there was a war with France.

He also helped his friend, Marie-Caroline de Bourbon-Sicile, duchesse de Berry. She wanted to put her son back on the French throne. In 1832, Charles Albert lent her money and a ship to transport volunteers to France. But the plan failed, and Marie-Caroline was arrested.

How He Ruled

Charles Albert was also conservative in how he governed his own country. He appointed ministers who shared his traditional views. In 1831, Giuseppe Mazzini, a revolutionary in exile, wrote to Charles Albert. He urged the king to unite Italy. But for a while, Charles Albert kept the same ideas as the kings before him.

Changes and Cultural Support

Despite his conservative views, Charles Albert did try to modernize the country. He created a Council of State to review laws. He also supported culture. In 1832, he founded an art gallery and a library in the Royal Palace. He also built monuments and palaces. In 1833, he restarted the Academy of Art as the Accademia Albertina. He also created a "Royal Foundation for the Study of the History of the Fatherland."

Charles Albert also worked to improve the economy. He reduced taxes on grain and allowed raw silk to be exported. He lowered taxes on imported raw materials like coal and metals. He also supported buying industrial machines from other countries. These changes helped the kingdom's finances improve.

He also reformed the army and the laws. He created new civil, criminal, and commercial laws. He also ended feudalism in Sardinia in 1838. He allowed new banks to open and reformed government agencies.

Supporting Traditional Rulers in Spain and Portugal

After the death of King Ferdinand VII of Spain, Spain was divided. Some supported traditional rulers, while others wanted a constitution. Charles Albert sided with the traditionalists. But in the Carlist War (1833–1840), the constitutionalists won.

Similarly, in Portugal, Charles Albert supported the traditional side in their civil war (1828–1834). But again, the liberals, supported by Britain and France, were successful.

Against "Young Italy"

When Charles Albert became king, there were many revolts in Italy. Austria helped put down these uprisings. Charles Albert believed his alliance with Austria was very important.

The Kingdom of Sardinia also faced plots from revolutionaries. In 1833, two officers were arrested in Genoa. It was discovered they belonged to Giuseppe Mazzini's group, Young Italy. Charles Albert saw this group as very dangerous. He ordered a strict investigation. Many were condemned to death, but some, like Mazzini, had already fled the country. Charles Albert did not grant any pardons.

In 1834, Mazzini tried to organize an invasion of Savoy from Switzerland. But Charles Albert found out about the plan and set up an ambush. The invasion failed completely. Only a few plotters attacked a barracks. One police officer was killed. To honor him, Charles Albert created the first gold medal for bravery in Italian history. Meanwhile, Giuseppe Garibaldi, who was supposed to lead an uprising, fled and was also condemned to death.

Law Reforms

Because of these events, Charles Albert realized he needed to make reforms. He wanted to modernize the kingdom and meet the people's needs. He created a commission to write new laws.

This process took a long time. But in 1837, a new civil code was introduced. It was partly inspired by the Napoleonic Code. The king also helped write the new criminal code, published in 1839. Charles Albert wanted to limit the use of the death penalty. In 1842, new commercial laws and criminal procedure laws were also introduced. These laws gave more rights to those accused of crimes.

Growing Problems with Austria

In 1840, a crisis in the Middle East caused problems between France and other European powers. This made Charles Albert think about expanding his territory in Italy. At the same time, a trade dispute started between Turin and Vienna. Austria increased taxes on wine from Piedmont. Charles Albert threatened to build a railroad that would take trade away from Austria's port.

These were small disagreements at first. But in 1846, the Austrian Chancellor Metternich asked Charles Albert to make his position clear. Was he with Austria or with the revolutionaries? Charles Albert hesitated.

A Liberal King (1845–1849)

In 1845, revolutionary movements started in Italy. Charles Albert told Massimo d'Azeglio that if there was a conflict with Austria, he would fight for Italy's independence with all his might.

In June 1846, the new Pope, Pius IX, was elected. He immediately granted amnesty to political prisoners. He also protested when Austria occupied a city in the Papal States without permission. Charles Albert saw Pope Pius IX as a way to combine his loyalty with his old liberal ideas. He offered the Pope his support.

In September 1847, Charles Albert expressed his hope that God would help him lead a war for independence. These statements made Charles Albert much more popular. However, his government was still divided. Some ministers thought an anti-Austrian policy was too dangerous. Others, like Cesare Balbo and Count Cavour, supported it.

The people's demands for change grew stronger. In November 1847, Charles Albert implemented the Perfect Fusion. This extended reforms from the mainland to the island of Sardinia. In early 1848, news arrived that King Ferdinand II of the Two Sicilies had granted a constitution. Revolutions then spread across Europe. In March, revolutions broke out in Milan, Venice, and Vienna.

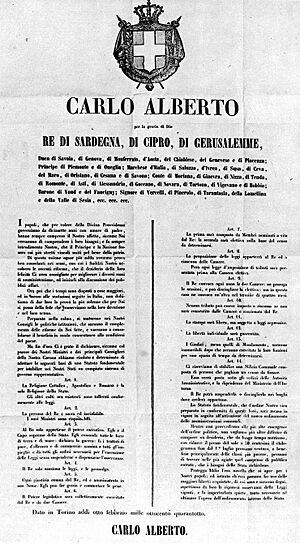

The Albertine Statute

On January 7, 1848, journalists in Turin met. Cavour suggested asking the king for a constitution. Most ministers also wanted a constitution. Charles Albert was unsure and thought about giving up his throne, like Victor Emmanuel I had done. But his son convinced him to stay.

On February 7, a special meeting was held. Many important people were there. Charles Albert listened silently for hours. Some were against a constitution. During a break, Charles Albert met with a group from the capital. They asked for a constitution for the good of the people.

Finally, Charles Albert agreed. He said he would approve the document if it clearly stated the importance of the Catholic religion and the honor of the monarchy. The meeting ended at dawn.

On February 8, a royal order was published in Turin. It outlined 14 articles that would form the basis of a representative government. The city celebrated with lights and demonstrations. The order said that Catholicism was the state religion. It also stated that the king held executive power and commanded the army. Legislative power would be shared between two chambers, one of which would be elected. Freedom of the press and individual liberty were guaranteed. The full version of the Statute was agreed upon and approved by Charles Albert on March 4, 1848. The first constitutional government was formed on March 16, 1848.

The Revolutions of 1848

In 1846, Pope Pius IX became popular with Italian liberals. He began to change old Vatican rules, allowing a free press and creating a civic guard. In January 1848, a revolt in Palermo forced King Ferdinand II to grant a constitution. Then, in February 1848, a revolution in France removed King Louis Philippe and created a republic. This wave of revolution spread to Milan on March 18, then to Venice, and finally to Vienna.

In Milan, people expected Charles Albert to declare war on Austria. On March 19, a message from Turin told the Milanese that Charles Albert would help them if they agreed to join the Kingdom of Sardinia.

On March 23, 1848, the Piedmontese embassy returned to Turin. They reported that the Austrians had left Milan. A temporary government in Milan asked Charles Albert to be their ally. The Milanese were not very keen on being annexed. They asked the king to keep his troops outside the city and to use the Italian tricolor flag.

Charles Albert agreed to the Milanese conditions. He only asked that the flag of the House of Savoy be placed in the middle of the tricolor. This flag then became the flag of the Kingdom of Sardinia and later of unified Italy. Charles Albert was about to go to war with a major power. On the balcony of the royal palace, he waved the tricolor flag with the Milanese representatives. The people cheered, "Long live Italy! Long live Charles Albert!" Within a year, his reign would be over.

First Italian War of Independence

On March 23, 1848, Charles Albert announced to the people of Lombardy and Veneto that Piedmontese troops were coming to help. He said they would fight for Italy's independence. This marked the start of the war.

Some, like Carlo Cattaneo, were not happy. He said, "Now that the enemy is in flight, the king wants to come with the whole army. He should have sent us anything... three days ago."

Early Battles

Charles Albert left Turin on March 26, 1848, to take command of the army. He was worried about Milan's delay in accepting annexation. The Austrians had gathered their forces at the River Mincio. Charles Albert entered Pavia in triumph on March 29. He slowly advanced towards the front lines.

On April 8 and 9, Italian sharpshooters won the first battle at Goito. Charles Albert won another victory on April 30 at Pastrengo. He fought on the front lines there. But on May 2, news arrived that Pope Pius IX had withdrawn his support for the Italian cause.

Even though the Pope withdrew, many Papal soldiers chose to stay and fight as volunteers. But Charles Albert had lost a key reason for his mission. His dream of uniting Italy under the Pope was gone. Still, the king continued to advance towards Verona. A tough battle was fought with the Austrians at Santa Lucia on May 6.

More bad news followed. On May 21, the King of Naples ordered his troops, who were on their way to fight Austria, to return home. On May 25, Austrian reinforcements joined their main army. Charles Albert was ambitious but not a great strategist. He could not realistically continue the war alone. The Battle of Goito and the surrender of Peschiera on May 30 were his last successes. The Austrians won a major victory over the Piedmontese at the Battle of Custoza from July 22 to 27.

Meanwhile, on June 8, the people of Milan and Lombardy voted to join the Kingdom of Sardinia. But for Charles Albert, things were getting worse. His soldiers were tired and hungry. A war council suggested asking for a truce.

Milan and the Armistice

On July 27, 1848, the Austrians agreed to a truce. But they demanded that the Piedmontese army withdraw, surrender fortresses, and give up certain territories. Charles Albert was very upset. He said, "I would rather die!" and prepared to keep fighting.

However, his troops had to withdraw anyway. Charles Albert went to a palace in Milan. He ignored the Milanese people's wish to keep fighting. He negotiated the surrender of the city to the Austrians. In return, his army was allowed to leave safely.

The next day, the Milanese found out about the agreement and were furious. A crowd protested outside the palace. When the king appeared on the balcony, some even fired rifles at him. Charles Albert's second son and a general helped him to safety. That night, he left Milan with his army.

On August 8, an armistice (a temporary peace agreement) was negotiated with the Austrians. It was called the Armistice of Salasco. Charles Albert approved it, even though some people wanted to keep fighting.

The Second Campaign and Giving Up the Throne

Charles Albert was not proud of how the first war ended. He decided to break the armistice. On March 1, 1849, he spoke about war, and the parliament agreed. He formally remained commander of the army but chose a Polish general, Wojciech Chrzanowski, to lead the troops. On March 8, it was decided that the armistice would end on March 12. Hostilities would begin eight days later, on March 20.

The war restarted on March 20. On March 22, Charles Albert arrived in Novara. The next day, the Austrian general Radetzky attacked Novara with more soldiers. The Polish general made some big mistakes. Despite the bravery of the Piedmontese soldiers and Charles Albert himself, the Battle of Novara was a terrible defeat.

Back at the palace in Novara, the king said, "Further resistance is impossible. It is necessary to request an armistice."

Austria's demands were very harsh. They wanted to occupy certain areas and have the Lombards who fought against Austria handed over. Charles Albert asked his generals if they could make one last push. They said no. The army was broken, and many soldiers were looting. They even feared an attack on the king himself.

At 9:30 pm that night, Charles Albert gathered his sons and generals. He told them he had no choice but to give up his throne. They tried to change his mind. But hoping his son, Victor Emmanuel, could get better terms, Charles Albert ended the discussion. "From this moment, I am no longer the king; the king is Victor, my son."

Exile (1849)

Charles Albert's oldest son became King Victor Emmanuel II. He quickly agreed to an armistice with the Austrian general Radetzky on March 24, 1849. Victor Emmanuel II managed to get better terms than those offered before.

Journey to Portugal

Charles Albert left Novara just after midnight on March 23. His carriage traveled towards Vercelli. He was stopped at an Austrian checkpoint. Charles Albert identified himself as the Count of Barge, a title he actually held. The Austrian general questioned him, but it's not clear if he recognized the former king. After a captured soldier confirmed his identity, Charles Albert was allowed to pass.

The former king continued his journey through Italy, France, and Spain. On April 1, he was in Bayonne, France. On April 3, he received a message from Turin asking him to legally confirm his abdication.

Charles Albert continued his journey, often on horseback, despite being ill. He reached Portugal on April 15. Finally, on April 19, he arrived in Oporto. He may have planned to travel to America, but he had to stop because of his liver illness.

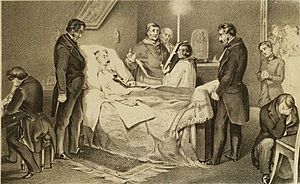

Last Days in Oporto

When people in Oporto learned of his arrival, Charles Albert stayed at a hotel. His condition worsened. He then moved to a private house with a view of the ocean. On May 3, he met with officials from the Piedmontese government.

During this time, Charles Albert's health got steadily worse. He suffered from coughing and abscesses. He had two heart attacks. Doctors believed his liver condition was the most serious problem. He ate very little and fasted often. He read letters and newspapers from Italy. He wrote to his wife sometimes, but regularly to the Countess of Robilant. He did not allow his mother, wife, or children to visit him.

In the month after his arrival, his health became very bad. From July 3, a doctor sent by Victor Emmanuel helped him. He could no longer get out of bed, and his coughing fits were frequent. He had a very difficult night on July 27. On the morning of July 28, he seemed better, but then he got worse after a third heart attack. A Portuguese priest gave him his last rites. Charles Albert whispered in Latin, "Into your hands, God, I entrust my spirit." He died at 3:30 in the afternoon, at just over 51 years old.

His body was prepared and displayed in the Cathedral of Oporto. On September 3, ships arrived to take his body home. On September 19, his body was placed on a ship that sailed to Genoa. It arrived on October 4. The funeral took place in Turin Cathedral on October 13. Many people attended. The next day, his body was buried in the crypt of the Basilica of Superga, where it remains today.

Family and Children

In 1817, Charles Albert married his second cousin once removed, Maria Theresa of Austria. She was the youngest daughter of Ferdinand III, Grand Duke of Tuscany. They had the following children:

- Victor Emmanuel II (1820–1878); he married Adelaide of Austria.

- Prince Ferdinand of Savoy (1822–1855), Duke of Genoa; he married Princess Elisabeth of Saxony.

- Princess Maria Cristina of Savoy (1826–1827) died when she was a baby.

Honors and Awards

Kingdom of Sardinia:

Kingdom of Sardinia:

- Knight of the Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation, 1816

- Founder of the Civil Order of Savoy, 1831

Austrian Empire:

Austrian Empire:

- Knight of the Military Order of Maria Theresa, 1823

- Grand Cross of the Royal Hungarian Order of St. Stephen, 1825

Spain: Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece, 1823

Spain: Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece, 1823 Kingdom of France: Knight of the Order of the Holy Spirit, 1824

Kingdom of France: Knight of the Order of the Holy Spirit, 1824 Russian Empire:

Russian Empire:

- Knight of the Order of St. George, 4th Class, 1824

- Knight of the Order of St. Andrew the Apostle the First-called, 1831

- Knight of the Order of St. Alexander Nevsky

Two Sicilies:

Two Sicilies:

- Grand Cross of the Order of St. Ferdinand and Merit

- Knight of the Order of Saint Januarius, 1829

Grand Duchy of Tuscany: Grand Cross of the Order of St. Joseph

Grand Duchy of Tuscany: Grand Cross of the Order of St. Joseph Kingdom of Prussia: Knight of the Order of the Black Eagle, 1832

Kingdom of Prussia: Knight of the Order of the Black Eagle, 1832 Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold, 1840

Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold, 1840

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Carlos Alberto de Cerdeña para niños

In Spanish: Carlos Alberto de Cerdeña para niños

- Statuto Albertino

- First Italian War of Independence

- Risorgimento