History of the Italian Republic facts for kids

The history of the Italian Republic is about the events in Italy since 1946. That year, Italy became a republic after a special vote where people chose to no longer have a king. This period is often split into two parts: the First Republic and the Second Republic.

After World War II and the end of the Fascist government, a political party called Christian Democracy (DC) was very powerful in Italy from 1946 to 1994. They were in charge for a long time, leading almost every government. The main opposing party was the Italian Communist Party (PCI). Christian Democracy usually governed with help from smaller parties. The Communist Party was mostly kept out of the government, except for a short time from 1976 to 1979 when they supported a Christian Democracy government from outside.

The political scene changed a lot in the early 1990s. This was due to two big events: the end of the Soviet Union in 1991, which affected the Communist Party, and a huge corruption scandal from 1992 to 1994. This scandal led to the collapse of almost all the old political parties, including Christian Democracy. People were very unhappy with the old system. In 1993, a vote changed how elections worked, moving from a system where seats were given based on how many votes a party got, to a mixed system that favored bigger parties.

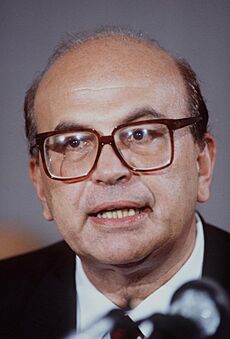

A media boss named Silvio Berlusconi entered politics with his conservative party, Forza Italia. He won the election in 1994 and became Prime Minister. He became a very important figure in Italian politics for the next two decades, serving as Prime Minister again from 2001 to 2006 and from 2008 to 2011. New conservative parties rose, while the old center and left parties joined together to form the Democratic Party (PD) in 2007. They competed against Berlusconi's group, which included Forza Italia and other right-wing parties.

When Berlusconi's government ended in 2011, a government led by experts, called the Monti Cabinet, took over until 2013. People were still not happy, which led to the rise of the Five Star Movement (M5S) and the Northern League (now just called the League). After the elections in 2013 and 2018, big coalition governments were formed, including these newer parties. The COVID-19 pandemic and its economic problems led to a national unity government led by Mario Draghi, who used to be in charge of the European Central Bank.

Contents

- Italy's Journey to a Republic

- The Birth of the Republic (1946–1948)

- The First Republic (1948–1994)

- The Second Republic (1994–Present)

- Silvio Berlusconi's First Government (1994–1995)

- Center-Left Governments (1996–2001)

- Berlusconi's Return (2001–2006)

- Romano Prodi's Government (2006–2008)

- Berlusconi's Third Term (2008–2011)

- Monti Government (2011–2013)

- Coalition Governments (2013–2021)

- Draghi Government (2021–2022)

- Meloni Government (2022–Present)

- Images for kids

- See also

Italy's Journey to a Republic

Early Ideas of a Republic

Italy has had different "republican" governments throughout its long history, like the ancient Roman Republic and the medieval maritime republics (city-states that were powerful in trade). Thinkers like Cicero and Niccolò Machiavelli wrote about how a republic should work. But it was Giuseppe Mazzini in the 1800s who really brought the idea of a republic back to life in Italy.

Mazzini was an Italian nationalist who believed in a democratic republic. He wanted Italy to be one united country, not split into many kingdoms. His ideas greatly influenced republican movements in Italy and Europe. He believed that thoughts and actions must go together, meaning you should always act on your ideas.

In 1831, Mazzini started the Young Italy movement. Its goal was to make Italy a single, democratic republic based on freedom, independence, and unity. This movement also wanted to remove the kings who ruled different parts of Italy. Young Italy was a key part of the Risorgimento, which was the movement to unify Italy. Other leaders, like Vincenzo Gioberti, wanted Italy to be united under the Pope, but Mazzini's ideas came first. Later, another thinker, Carlo Cattaneo, also supported a secular (non-religious) and federal republic, where power would be shared between a central government and local regions.

The plans of Mazzini and Cattaneo were challenged by Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, a prime minister, and Giuseppe Garibaldi, a famous general. Garibaldi put aside his republican beliefs to help unite Italy. After conquering southern Italy, he gave the lands to King Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia. This made many republicans angry, as they felt he had betrayed their cause. On March 17, 1861, Victor Emmanuel II was declared King of Italy, creating the Kingdom of Italy.

From 1861 to 1946, Italy was a monarchy with a constitution called the Albertine Statute. The parliament had a Senate, whose members were chosen by the king, and a Chamber of Deputies, elected by a small number of people. In 1861, only 2% of Italians could vote. There was a republican political movement during this time, and some of its members, like soldier Pietro Barsanti, became symbols of the republican ideal. Barsanti was executed in 1870 for supporting an uprising against the monarchy.

The Albertine Statute and Liberal Italy

At first, the Senate, made up of nobles and rich business people, had more power. But over time, the Chamber of Deputies became more important as the middle class and landowners gained influence. They cared about economic progress but also wanted to keep social order.

Republicans took part in elections. In 1853, they formed the Action Party with Giuseppe Mazzini. Even though he was in exile, Mazzini was elected in 1866 but refused his seat. Carlo Cattaneo was also elected but refused to swear loyalty to the monarchy. In 1873, Felice Cavallotti, a strong opponent of the monarchy, took his oath but declared his republican beliefs first. In 1882, new voting rules allowed more people to vote, increasing the number of voters to over two million, or 7% of the population. The Italian Socialist Party was formed in 1895. The Italian Republican Party was also established in 1895, and its members agreed to participate in the Kingdom's political life.

In Italian politics, the Socialist Party split into two groups: one that supported strikes and another that was more moderate and willing to work with the government. A nationalist movement also grew, as did a Catholic social movement. In 1904, Pope Pius X allowed Catholics to take part in politics. By 1912, a new law introduced universal male suffrage, meaning all adult men could vote. By 1914, Italy was considered one of the world's liberal democracies.

Fascism and World War II

After World War I, Italy's political life had four main groups. Two supported democratic development within the monarchy: the reformist socialists and the Italian People's Party. Two others challenged the monarchy: the Republican Party and the maximalist socialists. In the 1919 elections, parties favoring a republic won a good number of seats. However, less than 30% of elected officials wanted a republican government. In this situation, Benito Mussolini's Fascist movement grew. It gained support from people who were angry about the war's outcome, feared social unrest, and disliked revolutionary ideas. Many liberals and aristocrats saw Fascism as a way to stop these perceived dangers.

In October 1922, King Victor Emmanuel III appointed Benito Mussolini as Prime Minister after the march on Rome. This opened the door for a dictatorship. The Albertine Statute (the constitution) lost its power. Parliament became controlled by the new government. On June 27, 1924, 127 deputies left Parliament in protest, which allowed the Fascists to take full control of Italy for two decades.

Under Fascist laws (from 1926), all political parties in Italy were banned except the National Fascist Party. Some parties moved abroad, especially to France, and formed anti-Fascist groups. These groups included the Italian Republican Party and the Italian Socialist Party. Other groups, like the Italian Communist Party, stayed outside this coalition.

Meanwhile, secret anti-Fascist groups formed within Italy. These groups helped re-establish the Action Party, which was Mazzini's old republican party. Around 1942-1943, Alcide De Gasperi wrote ideas for a new Catholic-inspired party, which became Christian Democracy. It brought together older members of the Italian People's Party and young Catholics.

King Victor Emmanuel III not only asked Mussolini to form a government in 1922 but also did not act after the murder of politician Giacomo Matteotti in 1924. He accepted the title of emperor in 1936 and agreed to an alliance with Nazi Germany, leading Italy into World War II on June 10, 1940.

The war in Italy ended on April 29, 1945. Nearly half a million Italians died, society was divided, and the economy was destroyed. Income per person in 1944 was the lowest it had been in the 20th century.

The Birth of the Republic (1946–1948)

Towards the end of World War II, King Victor Emmanuel III was seen as having supported the Fascist government. To try and save the monarchy, he made his son, Umberto, "general lieutenant of the kingdom." The king promised that after the war, Italians could choose their government through a vote. In April 1945, Allied forces, helped by the Italian resistance movement, defeated the Fascist government and Benito Mussolini was killed. Like Japan and Germany, Italy was left with a ruined economy, a divided society, and anger towards the monarchy for its role with the Fascists. These feelings helped the republican movement grow stronger.

Victor Emmanuel officially gave up his throne on May 9, 1946. His son became King Umberto II of Italy. The special vote on whether Italy should be a monarchy or a republic was held on June 2. The republican side won with 54% of the votes, and Italy officially became a republic. The Kingdom of Italy was no more. This was the first time the entire Italian Peninsula was under a republican government since the end of the Roman Republic. The House of Savoy, Italy's royal family, was sent into exile. Victor Emmanuel went to Egypt, and Umberto, who had been king for only a month, moved to Portugal. There was some debate about the results of this vote, especially because the North voted strongly for a republic, while the South mostly supported the monarchy.

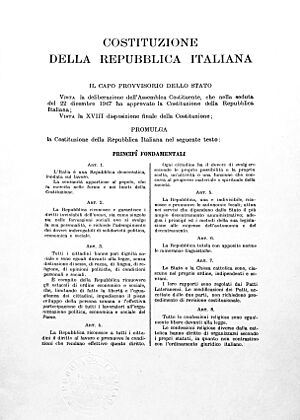

A Constituent Assembly, made up of representatives from all the anti-Fascist groups, worked from June 1946 to January 1948. They wrote the new Constitution of Italy, which started on January 1, 1948. A peace treaty between Italy and the Allies was signed in Paris in February 1947. In 1946, the main Italian political parties were:

- Christian Democracy (DC)

- Italian Socialist Party (PSI)

- Italian Communist Party (PCI)

Each party ran its own candidates in the 1946 election. Christian Democracy won the most votes. The Socialist and Communist parties received some government positions in a Christian Democrat-led group. However, by May 1947, both the Italian Communists and Socialists were removed from the government due to pressure from the United States.

Since the Socialist and Communist parties together had more votes than Christian Democracy, they decided to join forces in 1948 to form the Popular Democratic Front (FDP). The 1948 elections were heavily influenced by the growing Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States. After a Communist takeover in Czechoslovakia in February 1948, the US worried that the Soviet-funded Italian Communist Party might bring Italy into the Soviet sphere of influence if the left-wing group won the elections. The US sent many letters, especially from Italian Americans, urging Italians not to vote Communist. US agencies also broadcast propaganda and funded books and articles warning about the consequences of a Communist victory. The CIA was accused of funding center-right parties and spreading false information about Communist leaders. The Communist Party itself was accused of getting money from Moscow.

Fears of a Communist takeover greatly affected the election results on April 18. Christian Democracy (DC), led by Alcide De Gasperi, won a huge victory with 48% of the vote, their best result ever. The FDP only received 31%. The Communist Party gained a strong position as the main opposition party in Italy, though they never returned to government. For almost forty years, Italian elections were consistently won by Christian Democracy, a centrist party.

The First Republic (1948–1994)

Economic Growth and Social Changes (1950s and 1960s)

After the 1947 peace treaty, Italy lost some land to Yugoslavia, which led to many ethnic Italians leaving those areas. Italy also lost all its colonies. In 1950, Italian Somaliland became a United Nations territory under Italian rule until 1960. Italy's current borders have been in place since 1975, when Trieste officially became part of Italy again.

In the 1950s, Italy became a founding member of NATO (1949) and the United Nations (1955). It allied with the United States, which helped Italy's economy through the Marshall Plan. Italy also helped found the European Coal and Steel Community (1952) and the European Economic Community (1957), which later became the European Union. By the end of the 1950s, Italy experienced amazing economic growth, known as the "Italian economic miracle."

This economic boom had a huge impact on Italian society. Many people moved from the poorer South to the industrial cities of the North, especially to the "industrial triangle" between Milan, Turin, and Genoa. Between 1955 and 1971, about 9 million people moved within Italy, creating large cities. As Italy's economy doubled between 1950 and 1962, families bought things like refrigerators and washing machines for the first time. By 1975, most homes had these appliances, and 66% had cars.

Historian Paul Ginsborg noted that from 1950 to 1970, income per person in Italy grew faster than in any other European country. By 1970, Italy's income, which had been far behind northern European countries in 1945, reached 60% of France's and 82% of Britain's.

Christian Democracy's main support came from rural areas in the South, Center, and North-East. The industrial North-West had more left-leaning support due to its larger working class. An interesting exception was the "red regions" (like Emilia Romagna), where the Communist Party had strong support, partly due to local farming practices.

The Holy See (the Pope and the Vatican) strongly supported Christian Democracy. They said it would be a serious sin for a Catholic to vote for the Communist Party and even removed supporters from the church.

In 1953, a study found that 24% of Italian families were very poor, and many homes lacked basic facilities like running water or toilets. In the 1950s, important reforms were made, such as land reform and tax reform. However, the rapid growth also increased social differences, especially between older, skilled workers and new, less skilled immigrants from the South. A big gap between rich and poor still existed. By the late 1960s, about 4 million Italians were unemployed or underemployed. For these people, the "affluent society" might have meant a television, but little else.

During the First Republic, Christian Democracy slowly lost support as society changed. They considered working with the Socialist Party (PSI), which had become more independent after the 1956 events in Hungary. This "opening to the left" aimed to modernize the country and create a modern social democracy. In 1960, an attempt by some Christian Democrats to include the neo-Fascist Italian Social Movement in the government led to violent riots and failed.

Until the 1990s, Italian politics had two main types of government groups. The first were "centrist" groups led by Christian Democracy with smaller parties. These ruled from 1948 to 1963. The second type was the "center-left" group (Christian Democracy, Republicans, Social Democrats, Socialists), which started in 1963 when the Socialist Party joined the government. This group lasted for 12 years (1964-1976) and then returned in the 1980s until the early 1990s.

The Socialist Party joined the government in 1963. In the first year, many changes were made, including taxes on property profits, increased pensions, and the nationalization of the electric power industry. Wages for workers also increased significantly. The government tried to improve welfare services, hospitals, and education. For example, social security was extended to more people, and university entrance exams were removed in 1965. Despite these reforms, major problems like the mafia, social inequality, and differences between North and South Italy remained.

In 1965, an intelligence agency was changed after a failed attempt to give power to the police.

Italian society faced challenges from a growing left-wing movement, following student protests in 1968. This movement included protests by jobless farm workers and student occupations of universities. While conservative groups tried to reverse some social progress, many left-wing activists became frustrated with social inequalities. Some were inspired by guerrilla movements and the Chinese "cultural revolution," leading to extreme left-wing violent groups.

Social protests, especially from students, shook Italy during the "Hot Autumn" of 1969, leading to workers taking over the Fiat factory in Turin. Clashes also happened at La Sapienza university in Rome in 1968. Figures like Mario Capanna and groups like Potere Operaio were important in the student movement.

Years of Lead and Progress (1970s)

The late 1960s and 1970s became known as the "Years of Lead" because of a wave of bombings and shootings by both left-wing and right-wing extremist groups. In December 1969, several bombings occurred in Rome and Milan, including the Piazza Fontana bombing which killed 16 people.

During this period of terror attacks, the government was supported by most parties, including the Communists, who strongly opposed terrorist groups. However, the Communists were never part of the government itself, which was made up of five parties.

Despite the violence, the 1970s were also a time of great social and economic progress in Italy. Christian Democracy and its allies introduced many reforms. Regional governments were created in 1970, with power to make laws on public works, welfare, and health. Spending on the poorer South increased, and new laws improved pay, public housing, and pensions. In 1975, a law ensured that laid-off workers received at least 80% of their previous salary for up to a year. Living standards rose, with wages increasing by about 25% a year from the early 1970s. Workers also received many extra benefits, making their total pay among the highest in the Western world. Working hours were reduced, and some laid-off workers received generous unemployment payments. In 1975, a system that automatically raised wages with prices was strengthened, meaning wages often grew faster than the cost of living. By 1985, the average Italian was twice as rich as in 1960.

A law on worker's rights in 1970 greatly strengthened trade unions, banned unfair dismissals, and protected freedom of speech in factories. By the mid-1970s, Italy had some of the most generous welfare benefits in Europe, and Italian workers were among the best paid and protected.

Because of the reforms in the 1970s, Italian families in the 1980s had access to many more state services, such as recreational facilities, medicine subsidies, good medical care, and kindergartens. The income of most Italian families grew so much during the 1970s and 1980s that it was called a "watershed in the history of the Italian family." However, social and economic differences still existed. In 1983, over 18% of people in the South lived below the poverty line, compared to 6.9% in the North and Center.

Economic Changes and New Leaders (1980s)

The economy faced challenges until the mid-1980s, when reforms led to the Bank of Italy becoming more independent and a big reduction in how wages were linked to inflation. This brought inflation down from 20.6% in 1980 to 4.7% in 1987. This new economic and political stability led to a second "economic miracle," driven by exports from small and medium-sized businesses making clothes, shoes, furniture, and other goods. Because of this fast growth, in 1987 Italy's economy became the fourth richest in the world, after the US, Japan, and West Germany.

Meanwhile, the Socialist Party (PSI) was struggling. Its new leader, Bettino Craxi, worked to improve its standing. His rise brought new ideas to the First Republic, which was having trouble responding to changes in Italian society.

In the 1980s, for the first time since 1945, two governments were led by non-Christian Democrat Prime Ministers: Republican Giovanni Spadolini and Socialist Bettino Craxi. However, Christian Democracy remained the main party supporting the government.

As the "Years of Lead" ended, the Communist Party (PCI) slowly gained more votes under Enrico Berlinguer. The Socialist Party (PSI), led by Bettino Craxi, became more critical of the Communists and the Soviet Union. Craxi even supported the US placing missiles in Italy, which the Communists strongly opposed.

As the Socialist Party became more moderate, the Communist Party grew. In the 1984 European election, the Communist Party got more votes than Christian Democracy, which was the only time Christian Democracy was not the largest party in a national election they participated in. This happened just two days after Berlinguer's death, which likely brought sympathy. Huge crowds attended Berlinguer's funeral. In 1984, Craxi's government changed the 1929 agreements with the Vatican, ending Catholicism's role as Italy's state religion.

With the "Mani Pulite" (Clean Hands) investigation, which started just after the Soviet Union collapsed, widespread corruption was uncovered. This corruption involved most of Italy's major political parties, except the Communist Party. This led to the collapse of the entire political structure. The scandal became known as "Tangentopoli" (Bribesville). Parties like Christian Democracy and the Socialist Party broke apart. The Communist Party, though not heavily affected by the investigations, changed its name to the Democratic Party of the Left, becoming a more typical democratic party. This period was called the transition to the Second Republic.

Corruption Scandals and Political Change (1990s)

Italy faced several terror attacks between 1992 and 1993 by the Sicilian Mafia. These attacks were a response to harsh sentences given during a major trial against the Mafia and new anti-Mafia laws.

From 1992 to 1997, Italy faced big challenges. Voters were unhappy with political problems, huge government debt, widespread corruption, and the influence of organized crime. These issues, known as Tangentopoli, were uncovered by the "Mani Pulite" (Clean Hands) investigation. People demanded political, economic, and ethical reforms. The scandals affected all major parties, especially those in the government. Between 1992 and 1994, Christian Democracy went through a severe crisis and broke into several smaller parties. The Socialist Party and other smaller governing parties completely disappeared. This "revolution" in Italian politics happened while some reforms were being made, especially changes to election laws meant to reduce the power of political parties.

In 1993, voters approved major changes, including moving from a proportional voting system to a mixed system, which favored larger parties. They also voted to abolish some government ministries.

Major political parties, hit by scandals and losing voter trust, underwent big changes:

- The left-wing parties seemed close to winning a majority.

- The neo-Fascist Italian Social Movement changed its name to National Alliance, with its leader Gianfranco Fini calling it "post-Fascist."

- The Northern League gained a lot of support, especially in northern Italy, where some people wanted to separate from the rest of the country. Its leader, Umberto Bossi, attracted protest votes.

- Meanwhile, Silvio Berlusconi, a media tycoon, decided to create his own political party to prevent the left from winning the next elections. Just three months before the election, he announced his new party, Forza Italia, on TV. He used his power in communication (he owned Italy's three main private TV stations) and advanced advertising techniques to gain support.

Berlusconi managed to form alliances with both the National Alliance and the Northern League, even though these two parties were not allied with each other. Forza Italia worked with the League in the North and with the National Alliance in the rest of Italy. This unusual setup was due to the strong dislike between the Northern League, which wanted more regional independence, and the nationalist post-Fascists.

The left-wing parties formed a group called the Progressisti, but they didn't have as clear a leader as Berlusconi. Achille Occhetto, leader of the Democratic Party of the Left, was seen as their main figure.

The remaining parts of Christian Democracy formed a third, centrist group, proposing Mario Segni as their candidate for Prime Minister. They went back to the old name "Popular Party."

The election saw many new faces in parliament, with most deputies and senators being elected for the first time.

The Second Republic (1994–Present)

The 1994 elections marked the start of the Second Republic. These were the first elections to use the new voting system, adopted in 1993. The change from the First to the Second Republic was a shift within the political system, not a complete rewrite of the constitution. The republican constitution and most institutions remained the same as they had been since 1948. This term is used to highlight the differences in Italy's political structure before and after the 1992–1994 period, and its impact on the economy.

Silvio Berlusconi's First Government (1994–1995)

The 1994 election brought media boss Silvio Berlusconi to power as Prime Minister. His group, the House of Freedoms, included his party Forza Italia, the regionalist Lega Nord, and the National Alliance. However, Berlusconi had to step down in December 1994 because the Lega Nord withdrew its support due to disagreements over pension reform.

A government of experts led by Lamberto Dini then took over until early 1996.

Center-Left Governments (1996–2001)

A series of center-left governments led Italy from 1996 to 2001. They introduced several reforms, especially in social security. In April 1996, elections led to a victory for a center-left group led by Romano Prodi. This group, called The Olive Tree, included the Democrats of the Left and the Italian People's Party, with outside support from the Communist Refoundation Party. Prodi's government was one of the longest-lasting. His main goal was to improve Italy's economy so it could join the Euro currency. He achieved this in just over six months.

His government fell in 1998 when the Communist Refoundation Party stopped supporting him. This led to a new government led by Massimo D'Alema as Prime Minister. D'Alema's government was approved by a single vote. While D'Alema was Prime Minister, Italy took part in the NATO bombing of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1999. This action was supported by Berlusconi and the center-right, but strongly opposed by the far left. It was an important test of Italy's loyalty to NATO, as it was the first military action by a post-Communist Italian leader outside a UN mandate.

In May 1999, Parliament chose Carlo Azeglio Ciampi as the President of the Italian Republic. Ciampi was elected easily on the first try.

In April 2000, D'Alema resigned after his group performed poorly in regional elections. The next center-left government, with most of the same parties, was led by Giuliano Amato until the 2001 election.

A vote in 2001 confirmed a change to the constitution to introduce more federalism, giving more power to the regions instead of the central government.

Berlusconi's Return (2001–2006)

The May 2001 election brought a new center-right group, the House of Freedoms, back to power. It was led by Berlusconi's Forza Italia party and included the National Alliance and the Lega Nord. The center-left group, The Olive Tree, was in opposition.

Berlusconi's foreign policy focused on strong ties with the US, and positive relations with Russia and Turkey. He supported Turkey joining the EU, despite opposition from some of his allies. At the 2002 Rome summit, a NATO-Russia Council was created. Italy also led a group of countries trying to block Germany from getting a new seat on the UN Security Council, while supporting a single EU seat.

The 27th G8 summit in Genoa in July 2001 was the government's first big international event. Huge protests by demonstrators from all over Europe were met with strong police action.

Berlusconi sent Italian troops to the war in Afghanistan (2001) and to the US-led military group in Iraq in 2003. He always said Italy was taking part in a "peace operation," not a war outside the UN framework, which is not allowed by the Italian Constitution. This move was very unpopular, especially the involvement in Iraq, and led to many protests.

Italy's participation in the Iraq war, controlling the Nassiriya area, was marked by a bombing in 2003 that killed 17 soldiers. There was also an incident with the US in 2005 where an Italian agent was killed by friendly fire during a rescue mission.

In terms of laws, the government made changes to labor laws, making it easier for companies to be flexible. A law on Right of self-defense was also changed. The 2002 Bossi-Fini Act made immigration rules stricter. A point-system driver's license was introduced in 2003, and compulsory military service was replaced by a professional army in 2005. A constitutional reform that included more federalism and stronger executive powers was passed by Parliament but rejected by a public vote in 2006.

Berlusconi's time in office was criticized for passing "personal laws" that seemed to benefit him or his allies, especially in justice. These included laws about conflicts of interest, how judges could be removed, and laws that made it harder to prosecute certain crimes. A law in 2003 that protected the five highest state officials from criminal charges was later found to be unconstitutional. Other laws changed rules about how long cases could take and made it harder for prosecutors to appeal certain verdicts. Laws about the radio and TV market were also criticized for helping Berlusconi's media company.

Inside Italy, Berlusconi set up a commission to investigate alleged ties between left-wing politicians and the KGB. This commission was very controversial and closed in 2006 without a final report.

A new election law was created in 2005. It was a mixed system, where a party could join other parties in alliances. The group that got the most votes automatically won at least 26 seats. This law was strongly requested by some parties and agreed to by Berlusconi, though it was criticized for bringing back more proportional representation and for being introduced less than a year before the general elections. A rule was also added to make it easier for Italians living abroad to vote. Ironically, these votes proved crucial in helping the center-left win the 2006 elections.

Romano Prodi's Government (2006–2008)

Romano Prodi, leading a center-left group called The Union, won the April 2006 general election by a very small margin due to the new election law. Silvio Berlusconi at first refused to accept defeat. Prodi's group was very fragile because its small majority in the Senate meant almost any party could block laws. The parties in his group ranged from left-wing Communist parties to centrist Christian Democrats.

In foreign policy, Prodi's government continued Italy's involvement in Afghanistan under UN command, but withdrew troops from Iraq. Foreign Minister Massimo D'Alema focused on the aftermath of the 2006 Lebanon War, offering Italian troops for the UN force and taking command of it in February 2007.

Less than a year after winning the elections, on February 21, 2007, Prodi offered his resignation to President Giorgio Napolitano after his government lost a vote on foreign policy in the Senate by just two votes.

Berlusconi's Third Term (2008–2011)

Berlusconi won the snap elections in 2008 with his new party, the People of Freedom (a merger of his old Forza Italia and Fini's Alleanza Nazionale). He ran against Walter Veltroni of the Democratic Party.

Berlusconi's election campaign focused on issues like crime, the ongoing waste problem in Naples, the need to save the airline Alitalia, limiting wiretapping by prosecutors, and getting rid of local property taxes.

The 2008 Lodo Alfano Act (later declared unconstitutional) gave immunity from prosecution to the four highest political officials in Italy, including Berlusconi. The 2009 Maroni decree included measures against crime and illegal immigration. Local property tax was abolished the same year.

A friendship treaty was signed between Italy and Libya in 2008. The treaty aimed to resolve colonial issues, with Italy investing 5 billion euros in Libya's infrastructure over 20 years. It also included a promise not to act hostilely towards each other, which was criticized for potentially conflicting with Italy's NATO duties. Libyan leader Muammar al-Gaddafi visited Rome several times in 2009. Berlusconi's government was criticized for not being firm enough with Libya's government and not pushing for human rights.

The 2009 L'Aquila earthquake killed 308 people and left about 65,000 homeless. Berlusconi made the reconstruction a priority, though there were criticisms, especially from the people of L'Aquila. The 35th G8 summit in 2009 was quickly moved from La Maddalena to L'Aquila to help promote reconstruction efforts.

Berlusconi's international reputation suffered further in 2011 during the European debt crisis. Financial markets showed their disapproval, and the cost for Italy to borrow money increased greatly. Berlusconi resigned in November 2011, later blaming German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

Monti Government (2011–2013)

On November 12, 2011, President Giorgio Napolitano asked Mario Monti to form a new government of experts after Berlusconi resigned. Monti's government was made up of non-political figures but received wide support in Parliament from both the center-right and center-left. The Northern League was in opposition. Monti began to implement reforms and cut government spending.

Coalition Governments (2013–2021)

After the general election on February 24 and 25, 2013, the center-left group led by the Democratic Party won a clear majority of seats in the Chamber of Deputies. This was thanks to a bonus that tripled the number of seats for the winning group, even though they only narrowly won the popular vote against Silvio Berlusconi's center-right group. The new anti-establishment Five Star Movement became the third largest force. In the Senate, no group won a clear majority, leading to a hung parliament.

On April 22, 2013, President Giorgio Napolitano, after being re-elected, asked Enrico Letta, the vice-secretary of the Democratic Party, to form a government. This was because Pier Luigi Bersani, the leader of the winning center-left group, could not form a government without a Senate majority.

During the European migrant crisis of the 2010s, Italy was a main entry point for asylum seekers entering the EU. From 2013 to 2018, Italy took in over 700,000 migrants and refugees, mostly from Africa. This put a strain on public funds and led to increased support for far-right or anti-EU political parties.

Letta's government lasted until February 22, 2014, when it fell apart after the Democratic Party withdrew its support in favor of Matteo Renzi, the mayor of Florence. Renzi became Prime Minister, leading a new large coalition government. Renzi's government was the youngest in Italy's history, with an average age of 47. It was also the first with an equal number of male and female ministers.

On January 31, 2015, Sergio Mattarella, a judge and former minister, was elected President of the Italian Republic. He was supported by the government parties and others. Mattarella replaced Giorgio Napolitano, who had served for nine years, the longest presidency in the history of the Italian Republic.

Renzi's government passed several new laws: labor laws were reformed, same-sex unions were recognized, and a new election system was approved. However, the election system was later abolished by the Constitutional Court. The government also tried to change the Constitution to reform Parliament's structure and powers. But when people voted on this reform in 2016, the majority (59%) voted against it.

Renzi and his government resigned. President Mattarella then appointed Paolo Gentiloni, Renzi's foreign minister, as the new Prime Minister. Gentiloni led Italy until the 2018 Italian general election, where the anti-establishment Five Star Movement became the largest party in Parliament.

Through an alliance with Matteo Salvini's anti-EU Lega Nord, the Five Star Movement proposed Giuseppe Conte as the new Prime Minister of a coalition government. After an initial attempt failed, Conte formed the new government.

However, in August 2019, after the 2019 European Parliament election where the Lega Nord gained more votes than the Five Star Movement, and tensions between the parties increased, the Lega Nord proposed a no-confidence vote against Conte. Conte then resigned. After more discussions, President Mattarella reappointed Conte as Prime Minister in a coalition government between the Five Star Movement and the Democratic Party.

In 2020, Italy was hit by the COVID-19 pandemic. The Italian government put in place strict measures like social distancing and lockdowns to slow the spread of the virus. In January 2021, after weeks of tension, Conte's government lost the support of a political party led by former Prime Minister Renzi. Conte then had to resign.

Draghi Government (2021–2022)

Because of the serious economic and pandemic crises, President Mattarella appointed a new Prime Minister for a large coalition government: Mario Draghi, the former President of the European Central Bank. Draghi led a government with the support of almost all political parties in Parliament, except the right-wing party Brothers of Italy.

Thanks to many vaccine doses, the vaccination campaign against COVID-19 sped up. By the end of 2021, 85% of the population over 12 was vaccinated. A National Recovery and Resilience Plan was also created to use funds from the European Union to help Italy recover.

In January 2022, Italian President Sergio Mattarella was re-elected for a second seven-year term.

On July 21, 2022, after a government crisis where several parties withdrew their support, Prime Minister Draghi resigned. President Sergio Mattarella then dissolved Parliament and called for a snap election. This resulted in the center-right coalition winning a clear majority of seats.

Meloni Government (2022–Present)

On October 22, 2022, Giorgia Meloni became Italy's first female prime minister. Her Brothers of Italy party formed a right-wing government with the League and Forza Italia of former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi. The Meloni government is the 68th government of the Italian Republic. It was formed very quickly and was seen as a shift to the political right, and the first far-right-led government in Italy since World War II.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Italia desde 1946 para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Italia desde 1946 para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |