History of coins in Italy facts for kids

Italy has a really long and interesting history when it comes to coins! For thousands of years, different types of money have been used here. Some coins from Italy were super important in Europe. For example, the Florentine florin, made in Florence in the 1200s, was one of the most used coins in European history. The Venetian sequin, made from 1284 to 1797, was also a very famous gold coin used in trade across the Mediterranean Sea.

Even though the first Italian coins were used by the ancient Greeks in southern Italy and the Etruscans, the Romans later created a money system that was used everywhere. Unlike many coins today, old Roman coins had real value because they were made of precious metals. Later, early modern Italian coins looked a lot like French money because France ruled parts of Italy during the time of Napoleon.

For many centuries, Italy was split into many different states, and each had its own money. But when Italy became one country in 1861, the Italian lira was created. It was used until 2002. The word "lira" comes from "libra," a large unit of money used in Europe for a long time. In 1999, the euro became Italy's official money, and the lira was linked to it. Then, in 2002, euro coins and notes replaced the lira completely.

Contents

- Ancient Coins

- Medieval and Renaissance Coins

- Modern Era Coins

- Papal States Scudo

- Parman Lira

- Sardinian Scudo

- Two Sicilies Oncia

- Two Sicilies Tornesel

- Luccan Lira

- Piedmontese Scudo

- Tuscan Lira

- Sicilian Piastra

- Neapolitan Piastra

- Two Sicilies Piastra

- Neapolitan Lira

- Sardinian Lira

- Roman Scudo

- Tuscan Florin

- Lombardo-Venetian Lira

- Lombardy-Venetia Florin

- Papal Lira

- Modern Italian Money

Ancient Coins

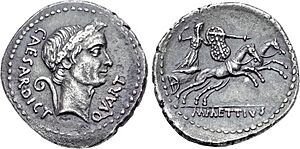

The first coins in Italy were used by Greek settlers in southern Italy (called Magna Graecia) and by the Etruscans. But it was the Romans who created a money system that spread across all of Italy. Roman coins were special because their value came from the metal they were made of, like gold or silver.

The Greek coins in Italy came from the many city-states that Greek migrants built in southern Italy and Sicily. Each city made its own coins. Taranto was one of the busiest cities, making coins mostly from silver and sometimes gold. Later, some of these Greek coins changed as the Romans took over.

The Etruscans also made coins for a short time. Their system mixed the old way of weighing bronze with the newer idea of striking silver and gold coins, which was common in southern Italy.

During the Social War (91–87 BC), Italian allies fought against Rome and made their own coins. These coins were inspired by the Roman denarius. They even had the word "ITALIA" on them, showing a goddess who represented Italy. These coins continued to be used even after the war ended.

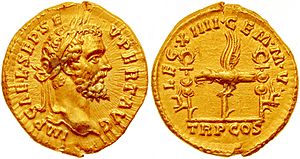

For most of Roman history, their money included gold, silver, bronze, and copper coins. From when they first started making coins in the 200s BC, through the time of the Roman Empire, Roman money changed a lot. Coins often lost value over time, meaning they had less precious metal in them.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Roman solidus coin was still used for a while. Its name even changed into "sol" and then "sou" in French. Other groups who settled in the Roman Empire also made coins that copied the Roman system. Many modern money names, like the British pound and the Arabic dinar, come from Roman coin names.

The way Romans made coins, starting around the 300s BC, greatly influenced how coins were made in Europe later. The word "mint" (a place where coins are made) comes from the Roman temple of Juno Moneta, where silver coins were made in 269 BC. This goddess became linked to money itself. Roman mints were all over the Empire and were sometimes used to spread messages. People often learned about a new Roman Emperor when coins with his face appeared.

Roman coins were worth more than just the metal they contained. For example, a coin might have been worth about 1.6 to 2.85 times its metal content. This was because the government guaranteed its value.

Medieval and Renaissance Coins

Italy was very important in the history of coins during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. The Florentine florin, made in Florence in the 1200s, became one of the most important coins in Western history. The Venetian sequin, made from 1284 to 1797, was the most respected gold coin used in trade around the Mediterranean Sea.

Lombard Coins

Lombard coinage refers to the coins made by the Lombards, a Germanic people who settled in Italy after the Roman Empire fell. They made coins in two main areas: in northern Italy from the late 500s to 774, and in the southern Duchy of Benevento from about 680 to the late 800s. Only a few collections of these coins have been found.

Florentine Florin

The Florentine florin was made from 1252 to 1523. Its design and the amount of gold in it hardly changed. It weighed about 3.5 grams of pure gold. The name of the coin comes from the Giglio bottonato, which was the flower symbol of Florence. This symbol was shown on the coin.

The gold florin was the first European gold coin made in large enough amounts to be important for trade. It was recognized across much of Europe. While the lira was used for smaller daily purchases, the florin was used for bigger things like dowries, international trade, or taxes.

The florin is one of the most important coins in Western history. When it was first made in 1252, its value was equal to the lira. But by 1500, the florin had become much more valuable, with one florin being worth seven lire. The original Florentine florins had the city's fleur-de-lis symbol on one side. On the other side was a picture of St. John the Baptist. The Dutch guilder and the Hungarian forint are both named after the florin.

Venetian Sequin

The sequin was a gold coin made by the Republic of Venice starting in the 1200s. The design of the Venetian sequin stayed the same for over 500 years, from 1284 until Venice fell in 1797. This made it the most respected gold coin in trade centers around the Mediterranean Sea. No other coin design has been made for such a long time!

One side of the coin had a Latin saying that meant, "Christ, let this duchy that you rule be given to you." The other side showed Mark the Evangelist, the patron saint of Venice. He was shown holding the Gospel and offering a flag to the Doge of Venice, who was kneeling. The Doge was the leader of Venice.

The quality of these coins was better than other coins of that time. This shows that the artists at the Venice Mint were very skilled. At first, the coin was called a "ducat," but it was later called a zecchino after the Zecca (the mint) of Venice. This change happened in 1543 when Venice started making a silver coin also called a ducat.

Venetian Grosso

The Venetian grosso was a silver coin first made in the Republic of Venice in 1193. It weighed about 2.18 grams and was almost pure silver. It was worth 26 denarii. Its name means "large penny." Its value changed compared to other Venetian coins until it was set at 4 soldini in 1332.

The story goes that the Venetian grosso was introduced to help pay for the ships needed for the Fourth Crusade in 1202. Even if it started a bit earlier, a lot of silver came in to pay for the crusaders' ships, leading to many grossi being made. It was initially called a ducatus argenti because Venice was a duchy. It's also known as a matapano, a Muslim term for the seated figure on the coin.

Venetian Lira

The Venetian lira was the money of the Republic of Venice until 1848. It came from the Carolingian monetary system used in much of Europe since the 700s. The lira was divided into 20 soldi, and each soldo was divided into 12 denari.

Over its 1,000-year history, the Venetian lira lost a lot of its value. The original unit was called the lira piccola (small lira) after 1200 AD. The denaro or piccolo was the only coin made between 800 and 1200 AD. It started with 1.7 grams of silver but by 1200 AD, it had only 0.08 grams.

After the Age of Discovery in the 1500s, Italy's money systems became less important for European trade. Still, Venice kept making new coins. The scudo d'argento was introduced in 1578. The tollero was issued in 1797.

In the 1800s, the Venetian lira piccola was replaced by the Italian lira of the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy and the Lombardy-Venetian lira of the Austrian Empire. The Italian lira was brought back by the Republic of San Marco in 1848.

Genoese Lira

The Genoese lira was the money of the Republic of Genoa until 1797. The mint in Genoa started making coins around 1138. They introduced coins similar to those in the rest of Europe:

- The silver denaro in 1138.

- The silver grosso in 1172, worth 4 denari.

- The gold Genovino d'oro in 1252, around the same time as the Florentine florin.

- The testone or 1-lira coin before 1500, which was the highest-valued Italian coin unit in the late 1400s.

Genoese money became very important in the 1500s during the "Golden Age of Genoese banking." The Spanish Empire sent a lot of its wealth from the Americas through the Bank of Saint George. But as the Genoese banks and the Spanish Empire declined in the 1600s, the Genoese lira also lost a lot of its value.

Papal States Florin

The Pope's coins followed the Byzantine money system until the time of Pope Leo III. After that, they used the system from the Frankish Empire. Pope John XXII started using the Florentine system and made gold florins. The weight of these coins changed a lot until Pope Gregory XI made them go back to the original weight. But then they started to lose value again. There were two kinds of florins: the papal florin, which kept the old weight, and the florin di Camera. The ducat was also made in the papal mint from 1432. It was a coin from Venice that circulated with the florin. In 1531, the scudo took its place.

Papal States Giulio

The Giulio was a coin from the Papal States worth 2 grossi. It got its name from Pope Julius II (who was Pope from 1503–13). He made the coin heavier and more valuable in 1504. The Pope ordered changes to the money system. The carleni coins were changed and renamed giuli to tell them apart. They contained about 4 grams of silver. A few years later, in 1508, the silver content dropped. By 1535, it was down to 3.65 grams. The first giuli made by Julius II had the papal arms on one side and St. Peter and St. Paul on the other.

In 1540, Paul III made coins with 3.85 grams of silver that were called paoli. The name giulio was also used by other papal mints and some Italian ones. The last coin made with this name was a silver giulio made by Pius VII in 1817. It weighed 2.642 grams and was still worth 2 grossi or 10 baiocchi. The names paolo and giulio were used in Rome even when these coins were no longer made, to refer to the 20 baiocchi coin.

Papal States Paolo

The Paolo was a coin from the Papal States. This name was given to the giulio (worth 2 grossi) when Pope Paul III (who gave it its name) increased its silver content to 3.85 grams in 1540. The first coins made by Paul III had the papal arms on one side and St. Paul on the other.

When the French Revolutionaries arrived, a paolo was worth 14 soldi in Milan. In Rome in the 1800s, it was the common name for the 10 baiocchi coin. The names paolo and giulio were used in Rome until the time of Pius IX, even after these coins were no longer made. Other Italian states also used the name for their coins. In the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, a paolo was worth 8 crazie.

Lazian Baiocco

The baiocco was an old Italian coin used a lot in Central Italy, especially in Latium. Its name's origin is not clear. Its value was first like a shilling, but over centuries, it changed to be worth five quattrini, or twenty pennies. The size, weight, and value of the coin changed over time. Around the mid-1500s, it became so thin that it was nicknamed "Baiocchino" because it weighed less than 0.25 grams.

It changed many times, losing more and more silver and becoming a lower quality metal. It was even called "Baiocchella" during the time of Sixtus V (1585 to 1590). It disappeared after Italy became one country between 1861 and 1870, when the Italian lira was introduced.

Neapolitan Cavallo

The cavallo was a copper coin from southern Italy during the Renaissance. It was first made by King Ferdinand I of Naples in 1472. It got its name from the picture of a horse on one side.

The name was later used for coins of the same value but with different designs, like those made by Charles VIII of France in Naples in 1494. As its value went down, the cavallo was stopped in 1498. It was replaced by the doppio cavallo ("Double Cavallo"), also known as sestino, by Frederick I of Naples.

The cavallo was made again briefly under Philip IV of Spain in 1626. Larger versions (2, 3, 4, 6, and 9 cavalli) were made until Ferdinand IV. The last three cavalli coin was made in 1804. It was replaced by the tornese, which was equal to 6 cavalli.

Anconetan Agontano

The agontano was the money used by the Italian Maritime Republic of Ancona from the 1100s to the 1500s. It was a large silver coin, about 18-22mm wide, weighing 2.04–2.42 grams. Its value was similar to the Milanese soldo. Ancona started making its own coins in the 1100s as the city became more independent.

This coin, also called "Grosso Agontano," was very successful. Other cities in Marche, Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany, Lazio, and Abruzzo copied its design. For example, coins from Massa Marittima, Ravenna, Rimini, and Ferrara show its influence.

Milanese Soldo

The soldo was an Italian medieval silver coin. It was first made in the late 1100s in Milan by Emperor Henry VI. The name comes from the old Roman coin solidus.

It quickly became popular in Italy and was made in cities like Genoa and Bologna. In Venice, the soldo was made from the time of Francesco Dandolo onwards. It was even used after Venice was no longer a republic in 1797 and during Austrian rule, until 1862. In 1300s Florence, a soldo was worth 1/20 of a lira and 12 denari.

Neapolitan Gigliato

The gigliato, also called gillat or carlino, was a pure silver coin created in 1303 by Charles II of Anjou in Naples. It was also made in Provence from 1330. Its name comes from the lilies ("giglio") shown on one side, wrapped around a cross.

The coin weighed 4 grams. This type of coin was widely copied in the Eastern Mediterranean, especially by the Turks.

Charles II of Anjou's silver gigliato was the same size as the main silver coin of its time, the French gros tournois. It contained 4.01 grams of almost pure silver. Its design was more like French gold coins than Italian silver coins.

Bolognese Bolognino

The Bolognino was a coin made in Bologna and other cities in medieval Italy from the late 1100s to the 1600s.

The coin started in 1191 when Emperor Henry VI gave Bologna the right to make a silver denaro. In 1236, this coin was renamed Bolognino piccolo (Small Bolognino) when the Bolognino grosso (Big Bolognino) was introduced. The Bolognino grosso was worth 12 soldi and weighed 9 carats.

The grosso was adopted by other Italian towns and cities, like Ravenna and Rimini. Its value changed depending on the political and economic situation.

The bolognino was no longer made starting in the 1700s. However, larger versions, up to 100 bolognini, continued to exist. A golden bolognino, introduced in 1380, was worth 30 silver bolognini.

Sicilian Pierreale

The pierreale was a silver coin made by the Kingdom of Sicily between the reigns of Peter I (1282–1285) and Ferdinand II (1479–1516). It had the same weight and purity as the Neapolitan carlino and was sometimes called a carlino.

One side had the imperial eagle, a symbol favored by Peter I's queen. The other side had the arms of Aragon, representing Peter's home kingdom. This design was chosen to be different from the carlino. After Alfonso I took over Naples in 1442, he changed the design to show the seated ruler and the combined arms of Aragon and Naples.

Gold pierreali (worth ten silver ones) were made under Peter I, but rarely after that. Half and quarter pierreali were made between 1377 and 1410 and again during the reign of John (1458–1479).

Sicilian Augustalis

An augustalis was a gold coin made in the Kingdom of Sicily starting in 1231. It was issued by Frederick II, who was both Holy Roman Emperor and King of Sicily. These coins were made until he died in 1250. There was also a half augustalis, which looked the same but was smaller and weighed half as much. The name augustalis means "of the august one," referring to the emperor and linking it to the Roman Emperors, who were often called Augustus.

The augustalis had a Latin inscription and was used widely in Italy. It was designed after the Roman aureus. It was made in Brindisi and Messina. The augustalis is known for its beautiful and early Renaissance style. It was made with high quality and purity. It weighed about 5.31 grams and was 20½ carats pure.

Modern Era Coins

Early modern Italian coins looked a lot like French francs, especially in their decimal system. This was because Italy was ruled by France during the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy. These coins were worth 0.29 grams of gold or 4.5 grams of silver.

Papal States Scudo

The Papal States scudo was the money system used in the Papal States until 1866. It was divided into 100 baiocchi, and each baiocco was divided into 5 quattrini. Other coins included the grosso (5 baiocchi), the carlino (7½ baiocchi), the giulio and paoli (both 10 baiocchi), the testone (30 baiocchi), and the doppia (3 scudi).

Between 1798 and 1799, French revolutionary forces created the Roman Republic. They made coins in baiocco and scudo values. Other states also changed their money system to match the Roman Republic. The Popes hired the best artists to make their coins.

In 1808, the Papal States became part of France, and French francs became the official money. When the Pope's power was restored in 1814, the scudo was brought back. However, individual states did not start making their own coins again. In 1849, another Roman Republic was formed and issued coins.

In 1866, the scudo was replaced by the lira, which was equal to the Italian lira. The exchange rate was 5.375 lire for 1 scudo.

Parman Lira

The Parman lira was Parma's official money before 1802. It was brought back from 1815 to 1859. The Duchy of Parma had its own money system until it became part of France in 1802. This lira was divided into 20 soldi, and each soldo into 12 denari. The sesino was worth 6 denari, and the ducato was worth 7 lire. The French franc replaced this money.

After Parma became independent again, the Parman money system was brought back in 1815. Also called the lira, it was divided into 20 soldi or 100 centesimi. This lira was equal to the French franc and the Sardinian lira, and it was used alongside them. It weighed 5 grams and was 9/10 pure silver. Since 1861, Parma has used the Italian lira.

Sardinian Scudo

The Sardinian scudo was the money of the Kingdom of Sardinia from 1720 to 1816. It was divided into 2½ lire, each of 4 reales, 20 soldi, 120 cagliarese, or 240 denari. The doppietta was worth 2 scudi. It was replaced by the Sardinian lira.

In the late 1700s, coins were made in different values: 1 and 3 cagliarese (copper), 1 soldo and ½ and 1 reale (billon), ¼, ½ and 1 scudo (silver), and 1, 2½ and 5 doppietta (gold).

Two Sicilies Oncia

In southern Italy, the oncia was a unit of account during the Middle Ages. Later, it became a gold coin made between 1732 and 1860. It was also made in the Spanish territories of southern Italy. A silver coin of the same value was made by the Knights of Malta. The name comes from the old Roman uncia. It can sometimes be translated as "ounce."

In the medieval kingdoms of Naples and Sicily, one oncia was equal to 30 tarì, 600 grani, and 3600 denari (pennies). Even though the oncia was never made as a coin in the Middle Ages, it was the main unit for keeping track of money. Smaller coins like the ducat (six equaled an oncia) and the carlino (60 to an oncia) were made. Frederick II introduced the augustalis, which was a quarter of an oncia.

Two Sicilies Tornesel

The tornesel was a silver coin used in Europe in the late Middle Ages and early modern times. Its name came from the denier tournois, a coin from Tours, France.

Marco Polo mentioned the tornesel in his travel stories to East Asia when describing the money of the Yuan Empire. The tornese was a smaller unit of the Neapolitan, Sicilian, and Two Sicilies ducats.

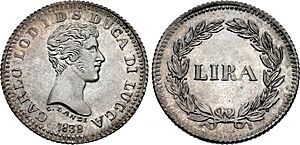

Luccan Lira

The Luccan lira was the money of the Republic of Lucca until 1800 and again of the Duchy of Lucca between 1826 and 1847. It was divided into 20 soldi, each of 3 quattrini or 12 denari. The lira was used until 1800, when the French franc was introduced. After Napoleon's fall, Lucca had no official money and used old francs, Tuscan lira, and Tuscan fiorino. The Luccan lira came back in 1826, replacing all other money.

The Luccan lira had less silver than the Tuscan lira. Lucca became part of Tuscany in 1847, and the Luccan lira was replaced by the Tuscan fiorino. In 1826, coins were made in different values: 1, 2, and 5 quattrini, 1, 2, 3, 5, and 10 soldi, and 1 and 2 lire. The quattrini and 1 soldo coins were copper, and the higher values were silver.

Piedmontese Scudo

The Piedmontese scudo was the money of Piedmont and other parts of the Savoyard Kingdom of Sardinia from 1755 to 1816. It was divided into 6 lire, each of 20 soldi or 240 denari. The doppia was worth 2 scudi. During the French occupation (1800–1814), the French franc was used. The scudo was replaced by the Sardinian lira.

In the late 1700s, various coins were used: copper 2 denari, billon ½, 1, 2½ and 7½ soldi, silver ¼, ½ and 1 scudo, and gold ¼, ½, 1, and 2½ doppia coins. In the 1790s, copper 1 and 5 soldi, and billon 10, 15 and 20 soldi were added. The Piedmont Republic made silver ¼ and ½ scudo in 1799. This was followed in 1800 by bronze 2 soldi coins.

Tuscan Lira

The Tuscan lira was the money of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany until France took it over in 1807. After that, it was still used unofficially because of its silver value until Tuscany became independent again in 1814. It was finally stopped in 1826. It was divided into 20 soldi, each of 3 quattrini or 12 denari. Other coins included the crazia (5 quattrini), the grosso (20 quattrini), the paolo (40 quattrini or 2/3 lira), the testone (3 paoli), and the large francescone (10 paoli or 6 2/3 lire).

In 1803, the Tuscan lira was worth 0.84 French francs or 3.78 grams of pure silver. In 1826, it was replaced by the Tuscan fiorino. In the late 1700s, copper coins were used, along with billon and silver coins. In the early 1800s, more copper and silver coins were added. The 10-lira coin was called dena, and the 5-lira coin was called meza-dena ("half-dena").

Sicilian Piastra

The Sicilian piastra was the special money of the Kingdom of Sicily until 1815. To tell it apart from the piastra made on the mainland (Kingdom of Naples), it's called the "Sicilian piastra." These two piastra coins were equal in value but were divided differently. The Sicilian piastra was divided into 12 tarì, each of 20 grana or 120 piccoli. The oncia was worth 30 tarì (2½ piastra).

In 1815, a single piastra currency was introduced for the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, called the Two Sicilies piastra. Old documents show that the money system was: 1 oncia = 30 Tarì, 1 Taro = 20 Grani, 1 Grano = 6 piccioli. The name piastra was not used in these old documents. A common Sicilian coin today is the 120 grana silver piece, which weighs an ounce and is sometimes called one piastre.

Neapolitan Piastra

The Neapolitan piastra was the most common silver coin of the Kingdom of Naples. To tell it apart from the piastra made on the island of Sicily, it's called the "Neapolitan piastra."

These two piastra coins were equal but were divided differently. The Neapolitan piastra was divided into 120 grana, each of 2 tornesi or 12 cavalli. There were also the carlino (10 grana) and the ducato (100 grana).

In 1812, the Neapolitan lira was introduced by the French to try and make the money system decimal. But it didn't work, and only the value of the cavallo changed to one-tenth of a grano. After the Bourbon family took back control, a single currency was made for all of the Two Sicilies, called the Two Sicilies piastra. This new piastra was divided in the same way as the Neapolitan piastra.

Two Sicilies Piastra

The Two Sicilies piastra was the money system of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies between 1815 and 1860. It was divided into 120 grana, each of 2 tornesi. Money was counted in ducato, which was worth 100 grana. The money system was made simpler compared to before Napoleon's time. Only three main types of coins remained. The ducat was the name for gold coins. The grana was the name for silver coins. The tornesel was the name for copper coins, worth half a grana.

The piastra was the unofficial name for the largest silver coin, which was worth 120 grana. When the Italian lira replaced the money of the Bourbon family in 1861, 1 piastra was set to be worth 5.1 lire.

Neapolitan Lira

The Neapolitan lira was the money of the mainland part of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (known as the Kingdom of Naples) between 1812 and 1815. This money was issued by Joachim Murat, who called himself "King of the Two Sicilies" but only controlled the mainland. So, it's called the "Neapolitan lira." It was divided into 100 centesimi and was equal to the Italian lira and French franc. It replaced the piastra, which came back into use after the Bourbon family returned to power.

Coins were made in values of 3, 5, and 10 centesimi, and ½, 1, 2, 5, 20, and 40 lire. The centesimi coins were bronze, the lire coins up to 5 lire were silver, and the higher values were gold. All the coins had the head of Joachim Murat and his Italian name, "Gioacchino Napoleone."

Sardinian Lira

The Sardinian lira was the money of the Kingdom of Sardinia from August 6, 1816, to March 17, 1861. It was divided into 100 centesimi and was equal in value to the French franc (4.5 grams of silver). The French franc had been used in the Kingdom of Sardinia before, replacing the Piedmontese scudo by 1801.

Since the Sardinian lira was very similar to the French franc, it could be used in France, and French coins could be used in Piedmont (the mainland part of the Kingdom of Sardinia). The Sardinian lira was replaced by the Italian lira in 1861, as Italy became one country. Like most money in the 1800s, the Sardinian lira did not have much inflation during its existence.

On each coin, the king was called in Latin "King of Sardinia, Cyprus and Jerusalem by the Grace of God" on the front. On the back, he was called "Duke of Savoy, Genoa and Montferrat, Prince of Piedmont and so on."

Roman Scudo

The Roman scudo was the money of the Papal States from 1835 to 1866. It was divided into 100 baiocchi, each of 5 quattrini. Other coins included the grosso (5 baiocchi), the carlino (7½ baiocchi), the giulio and paoli (both 10 baiocchi), the testone (30 baiocchi), and the doppia (3 scudi). In 1866, the scudo was replaced by the Papal lira, which was equal to the Italian lira. This happened when the Papal States joined the Latin Monetary Union. The exchange rate was 5.375 lire for 1 scudo.

Besides coins for the whole Papal States, many individual cities also made their own money. In the late 1700s, this included coins from Ancona, Bologna, Perugia, and many others. Only in Bologna was the baiocco (also called the bolognino) divided into 6 quattrini. In 1808, the Papal States became part of France, and the French franc was used. When the Pope's power was restored in 1814, the scudo was brought back. However, outside Rome, only Bologna continued to make coins. In 1849, another Roman Republic was formed and issued coins.

Tuscan Florin

The Tuscan florin was the money of Tuscany between 1826 and 1859. It was divided into 100 quattrini. There was also a coin called the paolo, worth 40 quattrini.

During the Napoleonic Wars, Tuscany was taken over by France, and the French franc was introduced, along with its related Italian lira. The old Tuscan lira didn't disappear, which caused a lot of confusion. So, when Duke Leopold II came to power in 1824, he decided to introduce a new main currency. The Tuscan florin replaced the Tuscan lira.

In 1847, Tuscany took over Lucca, and the Tuscan florin replaced the Luccan lira. After a short time of revolutionary coins, the Tuscan florin was replaced in 1859 by a temporary currency called the "Italian lira", which was equal to the Sardinian lira.

Lombardo-Venetian Lira

The Lombardo-Venetian lira was the money of the Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia between 1822 and 1861. The lira was made of 4.33 grams of silver. Six lire were equal to the scudo, which was the same as the Austrian Conventionsthaler. So, they were not related to the older Venetian lira and Milanese scudo. The lira was divided into 100 centesimi (cents). Coins were made in Milan and Venice.

During the revolutions of 1848, the temporary government in Lombardy briefly stopped making the lira and instead made a special 5 Italian lire coin. After the revolutions and when Austrian money was brought back, copper coins were made lighter. For political reasons, the name on these popular coins was changed from Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia to the Austrian Empire.

Lombardy-Venetia Florin

The Lombardy-Venetia florin was the money of Lombardy-Venetia (which was just Venetia three years before) between 1862 and 1866. It replaced the Lombardo-Venetian lira. One florin was worth 3 lire. The florin was equal to the Austro-Hungarian florin. Even though it was divided into 100 soldi instead of 100 kreutzers, Austrian coins were used in Venetia.

The only coins made specifically for Venetia were copper ½ and 1 soldo pieces. The name soldo was chosen because the old kreutzer and soldo were both worth 1/120 of a Conventionsthaler.

The florin was replaced by the Italian lira. One lira was worth about 40½ soldi (1 florin was worth 2.469 lire). This rate matched the silver content of the lira and florin coins.

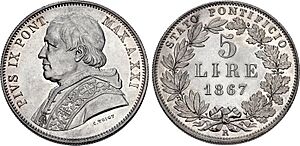

Papal Lira

The Papal lira was the money of the Papal States between 1866 and 1870. It was divided into 20 soldi, each of 5 centesimi. In 1866, Pope Pius IX, whose land was only the province of Latium, decided to join the Latin Monetary Union. A new currency, the lira, was introduced. It had the same value as the French franc and the Italian lira.

It replaced the scudo. One scudo was worth 5.375 lire. The lira was divided into 100 centesimi and, unlike other currencies in the union, into 20 soldi. However, all soldo values had an equivalent in cents. After joining the Union, the Pope's treasurer, Giacomo Antonelli, made the Papal silver coins less pure. When the Papal States became part of Italy in 1870, the Papal lira was replaced by the Italian lira at the same value.

Modern Italian Money

For centuries, Italy was divided into many different states, and they all had different money systems. But when the country became unified in 1861, the Italian lira was created and used until 2002. In 1999, the euro became Italy's official money, and the lira was linked to it. Then, in 2002, euro coins and notes replaced the lira completely.

Italian Lira

The Italian lira was the money of Italy between 1861 and 2002. It was first introduced by the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy in 1807, with the same value as the French franc. Later, the different states that formed the Kingdom of Italy in 1861 adopted it. It was divided into 100 centesimi, which means "hundredths" or "cents." The lira was also the money of the Albanian Kingdom from 1941 to 1943.

The word "lira" comes from "libra," the largest unit of the Carolingian monetary system used in Western Europe for a long time. This system is also where the French livre tournois (which came before the franc) and the British pound come from.

There was no single symbol for the Italian lira. Abbreviations like Lit. (for Lira italiana) and L. (for Lira), and symbols like ₤ or £ were all used. Banks often used Lit., which was recognized internationally. Handwritten notes and market signs often used "£" or "₤". Coins used "L." The name could also be written out fully, like "Lire 100,000." The international code for the lira was ITL.

When Italy became one country, it had to fix its money system. It decided to use both gold and silver, like the French franc, with a specific exchange rate between them. The Italian government introduced the new national currency, the Italian lira, just four months after the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy. Old coins could still be used for a while.

On August 24, 1862, a rule was made to stop using all other coins from the old states by the end of the year. The Italian lira was a direct continuation of the Sardinian lira. Other currencies replaced by the Italian lira included the Lombardo-Venetian lira, the Two Sicilies piastra, the Tuscan fiorino, the Papal States scudo, and the Parman lira. In 1865, Italy joined the Latin Monetary Union, where the lira was equal to the French, Belgian, and Swiss francs. In fact, until the euro came out in 2002, people in northwestern Italy often called the lira a "franc."

In 1866, because the government spent a lot of money (partly due to the Third Italian War of Independence), a system of paper money that couldn't be exchanged for gold was started. This lasted until 1881. In 1893, the Banca Romana bank had a big scandal and was closed. The Bank of Italy was then created, and it had to have at least 40% of the lire in circulation backed by gold.

King Victor Emmanuel III, who became king in 1900, was a coin expert and collector. He wrote a huge work describing Italian coins. During his reign, many different coins were made. When he stepped down as king, he gave his coin collection to the Italian state. Part of it is shown in the Roman national museum of Palazzo Massimo in Rome.

World War I broke the Latin Monetary Union and caused prices to rise a lot in Italy. Benito Mussolini tried to control inflation. In 1927, the lira was linked to the U.S. dollar at a rate of 1 dollar = 19 lire. This rate lasted until 1934. During World War II, after the Allies invaded Italy, the exchange rate was set at 1 US dollar = 120 lire. In German-controlled areas, 1 Reichsmark was worth 10 lire.

After the war, the Roman mint first made 1, 2, 5, and 10 lira coins in 1946. Italy joined the International Monetary Fund in 1947. The lira's value changed, but then Italy set it at 1 US dollar = 575 lire in 1947. This rate stayed until the early 1970s.

In 1973, major oil-producing countries greatly increased oil prices, causing an oil crisis that hit Italy's economy hard. This led to higher interest rates and a lot of government debt. The debt caused the lira to lose value compared to other European currencies. To fix this, the Bank of Italy raised interest rates very high in 1976.

The lira was Italy's official money until January 1, 1999, when it was replaced by the euro (euro coins and notes came out in 2002). Old lira money stopped being legal on February 28, 2002. The conversion rate was 1,936.27 lire to one euro. All lira banknotes and coins from after World War II could be exchanged for euros at the Bank of Italy until February 29, 2012.

Italian Euro Coins

The euro officially started being used in Italy on January 1, 2002. Italian euro coins have unique designs for each value. Many of these designs feature famous Italian artworks. Here's what's on the back of Italian euro coins:

- 1 euro cent coin: Castel del Monte, a castle from the 1200s.

- 2 euro cent coin: Mole Antonelliana, a tower that is a symbol of Turin.

- 5 euro cent coin: The Colosseum, a famous Roman amphitheater.

- 10 euro cent coin: The Birth of Venus painting by Sandro Botticelli.

- 20 euro cent coin: The Unique Forms of Continuity in Space sculpture by Umberto Boccioni.

- 50 euro cent coin: The Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius.

- 1 euro coin: Vitruvian Man, a drawing by Leonardo da Vinci.

- 2 euro coin: Dante Alighieri, a famous Italian poet and writer.

Each coin was designed by a different artist. All designs include the 12 stars of the EU, the year it was made, the letters "RI" for Repubblica Italiana (Italian Republic), and the letter R for Rome. There are no Italian euro coins dated earlier than 2002, even though they were made before then. They were first given to the public in December 2001.

The Italian public helped choose the coin designs through a TV show where people could vote. However, the 1 euro coin was not part of this vote. Carlo Azeglio Ciampi, who was the economy minister at the time, had already decided it would feature Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvian Man. This drawing is very symbolic because it shows how the Renaissance focused on humans. It also has a round shape that fits the coin perfectly. Ciampi said it represents "the coin to the service of Man," instead of people serving money.

Like in Finland and the Netherlands, Italy stopped making 1 and 2-cent coins from January 1, 2018. However, the coins already in use are still valid. It cost more to make a one-cent euro coin (4.5 cents) than its actual value. For the two-cent coin, it cost 5.2 cents to make.

In 1999, because of a mistake, over a million 20-cent coins were made with the wrong year (1999 instead of 2002). The mistake was found, and the mint ordered them to be destroyed. But some people managed to steal and circulate an unknown number of these coins. In 2002, the Italian mint mistakenly put the Mole Antonelliana (which should be on the 2-cent coin) on the back of some 1-cent coins instead of Castel del Monte. Numismatists (coin experts) have valued each of these error coins at more than 2,500 euros!

|

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |