History of the Republic of Venice facts for kids

The Republic of Venice was a powerful country and a "maritime republic" (a state that relied on sea trade and naval power) located in Northeast Italy. It existed for over a thousand years, from the 8th century until 1797.

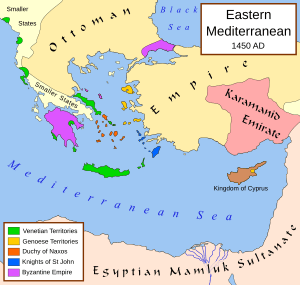

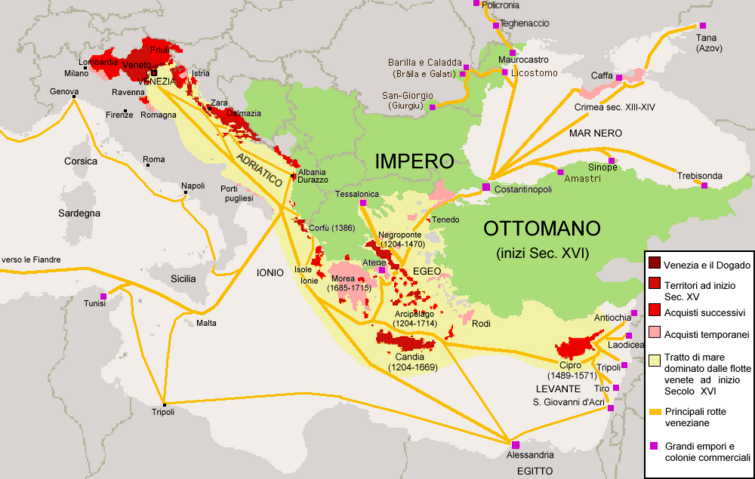

Venice was built on islands in a lagoon, which helped it become a very rich city. During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, it was a leading European power in trade and economics. It was the most successful of Italy's maritime republics. By the late Middle Ages, Venice controlled large areas of northern Italy, called the Domini di Terraferma. It also controlled most of the Dalmatian coast across the Adriatic Sea, plus Crete and many smaller colonies around the Mediterranean Sea. These overseas territories were known as the Stato da Màr.

Around 1500, Venice slowly started to lose its political and economic power. By the 18th century, the city of Venice mostly relied on tourism, much like it does today. Most of its overseas territories, the Stato da Màr, were lost.

Contents

How Venice Began

Even though there are no direct records about Venice's exact founding, people traditionally say the Republic of Venice started at noon on Friday, March 25, AD 421. Authorities from Padua supposedly founded a trading post there. The church of St. James is also said to have been founded at the same time, but it was likely built much later.

People believe that the first residents of Venice were refugees. They fled from nearby Roman cities like Padua, Aquileia, and Treviso, as well as from the countryside. They were escaping attacks from groups like the Huns and Germanic peoples between the 2nd and 5th centuries. Old documents support this, showing that some of Venice's founding families came from Roman families.

Invaders like the Quadi and Marcomanni destroyed Roman towns in the area around AD 166–168. Later, the Visigoths and Attila the Hun also attacked. The Lombards invaded in 568, causing great damage to the region called Venetia. This left the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire) with only parts of central Italy and the coastal lagoons of Venetia. Around this time, a writer named Cassiodorus mentioned the "lagoon dwellers" and how they used fishing and saltworks to strengthen their islands.

As the Byzantine Empire's power weakened in northern Italy in the late 7th century, the lagoon communities joined together for protection against the Lombards. This new group was called the Duchy of Venetia. Its isolated location helped it become more independent.

Choosing the First Leader

In the early 8th century, the people of the lagoon chose their first leader, Orso Ipato. The Byzantine Empire confirmed him as a dux (duke). Historically, Ursus was the first Doge of Venice (Doge means "duke" in the Venetian dialect). Some traditions say the first duke was Paolo Lucio Anafesto in 697, but this story appeared later. The first doges had their main power base in a town called Eraclea.

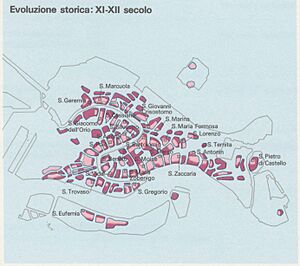

At first, the main settlement in the lagoon was not on the islands that would become the heart of Venice. One early settlement was on Olivolo island, which is now called S. Pietro in Castello. This island was inhabited in the 5th century and was politically important in the 6th and 7th centuries. The area that became the city of Venice, the Rialto islands, didn't really start to become a city until the 9th century.

Venice Grows Stronger

Teodato Ipato, Orso Ipato's son, moved the duke's seat from Eraclea to Malamocco in the 740s. He tried to start a ruling family, but like other early doges, he didn't succeed.

Venice's politics changed as the Frankish Empire grew. Some people wanted to stay loyal to the Byzantine Empire. Others wanted Venice to be truly independent. A third group, supported by the church, looked to the Frankish king, Pepin the Short, for protection against the Lombards. A smaller group wanted peace with the nearby Lombard kingdom.

After some political struggles, Domenico Monegario became doge. During his time, Venice changed from a fishing town to a busy trading port. Shipbuilding also improved greatly, setting the stage for Venice to control the Adriatic Sea. Two new officials were elected each year to oversee the doge and prevent him from abusing his power.

Venice also became involved in the slave trade during this period. They bought people in Italy and sold them to people in North Africa. Even Pope Zachary reportedly tried to stop this trade from Rome.

A New Era of Power

In 764, Maurizio Galbaio became doge. His long rule (764-787) helped Venice become important not just in its region but internationally. He also tried to establish a ruling family. Maurizio expanded Venice's influence to the Rialto islands. His son, Giovanni Galbaio, became doge after him. Giovanni had disagreements with Charlemagne over the slave trade and also with the Venetian church.

The idea of a ruling family ended when a pro-Frankish group took power under Obelerio degli Antoneri in 804. Obelerio brought Venice closer to the Carolingian Empire. However, when he asked Charlemagne's son, Pepin of Italy, for help, the people of Venice became angry. Obelerio and his family had to flee when Pepin besieged Venice.

Pepin's siege was a big failure for the Carolingians. It lasted six months, and Pepin's army suffered from diseases in the swamps. They eventually had to leave. Pepin himself died a few months later, possibly from a disease he caught there.

This event helped Venice gain lasting independence by successfully defending itself. An agreement between Charlemagne and Nicephorus later confirmed Venice as Byzantine territory but also recognized its trading rights along the Adriatic coast.

Early Middle Ages: Building a Republic

The doges who came after Obelerio inherited a united Venice. An agreement in 803 recognized Venice's independence, even though it was still officially part of the Byzantine Empire. During the rule of Agnello Participazio (around 810–827) and his two sons, Venice grew into its modern shape. Around 810, Agnello moved the duke's main office from Malamocco to an island in the Rialto group. This happened after Pepin of Italy attacked Malamocco but failed to invade the lagoon. This move started the development of the Rialto islands, which became the heart of modern Venice.

Agnello's time as doge saw Venice expand into the sea. They built bridges, canals, defenses, and stone buildings. Modern Venice, connected to the sea, was being born. Agnello's son, Giustiniano Participazio, brought the body of Saint Mark the Evangelist to Venice from Alexandria. Saint Mark then became the patron saint of Venice.

Under Pietro Tradonico, Venice began to build its military strength. This power would later influence many crusades and help Venice control the Adriatic Sea for centuries. Tradonico also signed a trade agreement with the Holy Roman Emperor Lothair I. He protected the sea by fighting Narentine and Saracen pirates. Tradonico's rule was long and successful (837–864).

In 840, Venice made an agreement with the Carolingian Empire called the pactum Lotharii. Venice promised not to buy Christian slaves from the Empire or sell Christian slaves to Muslims. After this, Venetians began to sell more non-Christian slaves from Eastern Europe. Caravans of slaves traveled from Eastern Europe through the Alps to Venice.

Around 841, the Republic of Venice sent a fleet of 60 galleys (large ships) to help the Byzantines fight the Arabs in Crotone, but they were not successful.

Under Pietro II Candiano, cities in Istria pledged loyalty to Venice. His father, Pietro Candiano I, tried to secure the Dalmatian Coast for Venice but was killed by pirates in 887. He was the only Duke of Venice to die trying to control the Dalmatian Coast. The Candiano family, who were very powerful, were overthrown in a revolt in 972. The people then elected Pietro I Orseolo as doge.

Controlling the Adriatic Sea

Starting with Pietro II Orseolo, who became doge in 991, Venice focused strongly on controlling the Adriatic Sea. Internal conflicts were settled, and trade with the Byzantine Empire increased thanks to a favorable treaty (the Grisobolus or Golden Bull) with Emperor Basil II. This special agreement allowed Venetian traders to be free from taxes that other foreigners and even Byzantines had to pay. This was a huge help for Venice to become wealthy and powerful, as it acted as a middleman for the valuable spice and silk trade routes from the Levant and Egypt.

On Ascension Day in 1000, a large fleet sailed from Venice to deal with the Narentine pirates. The fleet visited many cities in Istria and Dalmatia. Their citizens, tired of wars, swore loyalty to Venice. The main Narentine pirate strongholds tried to resist but were conquered and destroyed. The Narentine pirates were stopped for good. Dalmatia remained officially under Byzantine rule, but Orseolo became "Duke of Dalmatia," showing Venice's power over the Adriatic Sea. The "Marriage of the Sea" ceremony, a tradition where the Doge symbolically marries the sea, began around this time.

Venice's control over the Adriatic was further strengthened by an expedition led by Pietro's son, Ottone Orseolo, in 1017. By this time, Venice played a key role in balancing power between the Byzantine and Holy Roman Empires.

During a major dispute in the 11th century between the Holy Roman Emperor and the Pope about who could appoint church officials, Venice remained neutral. This caused some Popes to support Venice less. Doge Domenico Selvo helped the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos in a war against the Normans. In return, Venice gained a document declaring its supremacy along the Adriatic coast and freedom from taxes for its merchants throughout the Byzantine Empire. This was a huge factor in Venice's wealth.

The war itself wasn't a military success, but this agreement gave Venice almost complete independence. In 1084, Domenico Selvo led a fleet against the Normans but was defeated, losing many large ships.

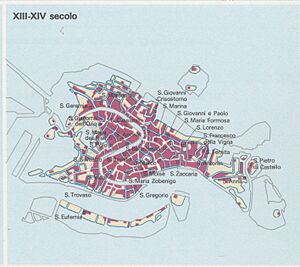

High Middle Ages: A Trading Empire

In the High Middle Ages, Venice became very rich by controlling trade between Europe and the Levant (the Eastern Mediterranean). It began to expand its influence into the Adriatic Sea and beyond. Venice was involved in the Crusades from the start. In 1110, a Venetian fleet of 100 ships helped capture the city of Sidon. In the 12th century, Venice built a huge national shipyard called the Venetian Arsenal. With new and powerful fleets, Venice took control of the eastern Mediterranean. The first exchange business in the world started in Venice, helping merchants from all over Europe.

Venetians also gained many trading rights in the Byzantine Empire, and their ships often served as the Empire's navy. However, in 1182, there was a terrible event in Constantinople where the Orthodox Christian population attacked and killed many Catholics, especially Venetians.

Venice's Power Grows

Venice was asked to provide ships for the Fourth Crusade. When the crusaders couldn't pay for the ships, Doge Enrico Dandolo offered to delay payment. In exchange, the crusaders had to help Venice recapture Zadar (today Zadar), which had rebelled against Venetian rule.

After capturing Zadar in 1202, the crusade was diverted to Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire. A deposed emperor, Alexios IV Angelos, offered the Crusaders a large sum of money and military help if they would restore him to power.

The Crusaders agreed and put Alexios back in charge in 1203. However, he didn't keep his promises. So, in 1204, the Venetians and French crusaders attacked and captured Constantinople. They looted the city, and the Venetians brought back many artworks, including the famous Horses of Saint Mark.

The Byzantine Empire was greatly weakened. In the division of the Empire that followed, Venice gained important territories in the Aegean Sea, including the islands of Crete and Euboea. Some cities, like Chania on Crete, still have Venetian-style buildings. These Aegean islands formed the Venetian Duchy of the Archipelago.

The Republic of Venice also signed a trade treaty with the Mongol Empire in 1241.

In 1295, Pietro Gradenigo sent fleets to attack the Genoese, Venice's rivals. In 1304, Venice fought a short "Salt War" with Padua.

In the 14th century, Venice faced challenges, especially from Louis I of Hungary. In 1346, he tried to free Zadar from Venice but failed. In 1356, an alliance formed against Venice, and Louis took Dalmatia.

Along the Dalmatian coast, his army attacked cities like Zadar, Traù, and Spalato. Venice suffered a major defeat in 1358 and was forced to sign the Treaty of Zadar. This treaty made Venice give Dalmatia back to the Kingdom of Hungary.

From 1350 to 1381, Venice fought many wars with the Genoese. After some defeats, the Venetians destroyed the Genoese fleet at the Battle of Chioggia in 1380. This helped Venice keep its important position in the eastern Mediterranean. However, the peace treaty meant Venice lost some territories to other countries.

In 1363, a revolt broke out in Crete that took five years and a lot of military force to put down.

Venice in the 15th Century

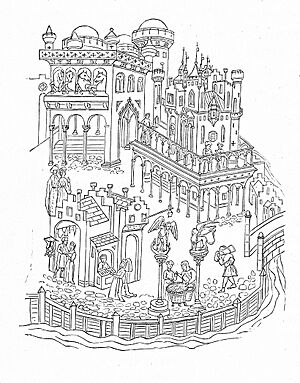

illustrated and printed in Mainz by Erhard Reuwich, 11 February 1486

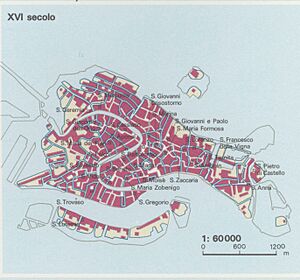

In the early 15th century, Venice expanded its lands in Northern Italy. It also took full control of the Dalmatian coast from Ladislaus of Naples. Venice sent its own noblemen to govern these areas. This expansion was partly to stop Giangaleazzo Visconti, Duke of Milan, from expanding his own territory. Venice also needed to control trade routes in northern Italy to keep its merchants safe. By 1410, Venice had a large navy and controlled most of the Veneto region, including important cities like Verona and Padua.

Under Doge Francesco Foscari (1423–57), Venice reached its greatest power and size. In 1425, a new war started against Filippo Maria Visconti of Milan. Venice won a victory that moved its western border further. However, tensions with Milan remained high, and Venice had to fight another alliance in 1446. After more fighting, the Peace of Lodi (1454) confirmed that Venice controlled areas like Bergamo and Brescia. At this time, Venice's territories included much of modern Veneto, Friuli, and parts of Lombardy. Its overseas lands included Euboea and Egina.

On May 29, 1453, Constantinople fell to the Ottomans. But Venice managed to keep a trading post there and some of its old trade rights. In fact, in 1454, the Ottomans granted Venetians access to their ports. Despite some Ottoman defeats, war was unavoidable. In 1463, the Venetian fort of Argos was destroyed. Venice allied with Hungary and attacked Greek islands and Bulgaria. However, they were forced to retreat. The Ottomans launched a huge attack in 1470, and Venice lost its main stronghold in the Aegean Sea, Negroponte.

Venetians tried to ally with Persia and other European powers, but they got little help. They could only make small attacks. The Ottomans conquered the Peloponnese and attacked the Venetian mainland. A revolt in Cyprus brought the island under Venetian control in 1473. However, another fort fell two years later, and Friuli was invaded again. On January 24, 1479, Venice signed a peace treaty with the Ottomans. Venice had to give up some territories and pay a yearly tribute.

In 1482, Venice allied with Pope Sixtus IV in his attempt to conquer Ferrara. After many battles, a peace treaty was signed in 1484. Venice gained some land and increased its influence in Italy. In the late 1480s, Venice fought short campaigns against the new Pope and Austria. Venetian troops also fought in the Battle of Fornovo against Charles VIII of France. Alliances with Spain helped Venice control ports in southern Italy and the Ionian islands.

Despite challenges, by the end of the 15th century, Venice was the second-largest city in Europe after Paris and likely the richest in the world. It had about 180,000 people. The Republic of Venice covered about 70,000 square kilometers and had 2.1 million people.

Administratively, the territory was divided into three parts:

- The Dogado: the city islands and the lands around the lagoon.

- The Stato da Mar: overseas territories like Istria, Dalmatia, Albania, Apulian ports, Ionian Islands, Crete, Aegean Archipelago, and Cyprus.

- The Stato di Terraferma: mainland territories like Veneto, Friuli, and parts of Lombardy.

In 1485, the French ambassador, Philippe de Commines, wrote that Venice was "the most splendid city I have ever seen, and the one which governs itself the most wisely."

Challenges and Conflicts (16th-17th Centuries)

In 1499, Venice allied with Louis XII of France against Milan, gaining some territory. In the same year, the Ottoman sultan attacked by land and sea. The Venetian fleet was defeated in the Battle of Zonchio in 1499. The Ottomans again raided Friuli. Venice preferred peace over a full war and gave up some bases to the Turks.

Venice became rich from trade, but its guilds also produced high-quality silks, jewelry, armor, and glass. However, Venice's attention was drawn away from its sea trade by the rich region of Romagna in Italy. Romagna was part of the Papal States but was hard for Rome to control. Eager to take some of Venice's lands, all neighboring powers formed the League of Cambrai in 1508, led by Pope Julius II. Everyone wanted a piece of Venice's territory.

On May 14, 1509, Venice suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Agnadello. French and Imperial troops occupied Veneto. This was one of the most difficult times in Venetian history. But Venice managed to recover through diplomacy. It gave up some ports to Spain, and Pope Julius II soon realized that destroying Venice would be dangerous. The people of the mainland rose up, and Venice recaptured Padua. Spain and the Pope broke their alliance with France, and Venice also regained some cities from France. After seven years of war, Venice got back its mainland territories. Although the defeat turned into a victory, the events of 1509 marked the end of Venice's expansion.

A book by Gasparo Contarini in 1544 described Venice's unique government system. It showed how amazed foreigners were by Venice's independence and its ability to survive the war against the League of Cambrai. Contarini suggested that Venice's greatness came from combining three types of government: monarchy, oligarchy, and democracy. He believed the Great Council was the democratic part, the Senate and the Council of Ten were the oligarchy, and the Doge represented monarchy.

The struggle for power in Italy between France and Spain ended with Spain winning. Caught between the powerful Spanish and Ottoman empires, Venice adopted a clever policy of being mostly neutral in Europe, but defensive against the Ottomans. In the Turkish war of 1537-40, Venice allied with the Holy Roman Emperor. The allied fleets were defeated at Preveza in 1538, and two years later Venice signed a peace treaty, losing some islands to the Turks. After Preveza, the Ottomans became the strongest naval power.

It became harder to find enough sailors for Venice's galleys. By 1545, Venice started using conscription, chaining oarsmen to the benches, as other navies did. By 1563, Venice's population had dropped to about 168,000 people.

Another war with the Ottomans started in 1570. Venice, Spain, and the Pope formed the Holy League, which gathered a large fleet. The Christian fleet met the Turkish fleet off Lepanto on October 7, 1571. The Christians won a great victory, capturing many Turkish ships. But Venice didn't gain much strategically. Famagusta, the last stronghold on Cyprus, had fallen to the Turks before Lepanto. The loss of Cyprus was confirmed in the peace treaty of 1573. By 1581, Venice's population had dropped further to 124,000 people.

17th Century Conflicts

In 1605, a conflict began between Venice and the Holy See (the Pope). Venice arrested two priests for minor crimes and passed a law limiting the Church's right to own land. Pope Paul V said these laws went against church rules and demanded they be removed. When Venice refused, he placed Venice under an interdict, which meant no church services could be held. The Republic, led by Doge Leonardo Donato, ignored the interdict. It was supported by a friar named Paolo Sarpi, who advised the government. The interdict was lifted after a year, with France's help. Venice was happy to confirm that no citizen was above the law.

Another war happened between 1613 and 1617. Venice was concerned about the Uzkoks, Christian refugees who were pirates in the Adriatic Sea. They were supported by the Austrian Habsburgs. When Venice acted against these pirates, it clashed with Austria. Venice sent an army and supported the Duke of Savoy, who was fighting the Spanish. The fighting on the eastern border wasn't decisive, but the peace terms in 1617 required the Habsburgs to move the Uzkoks inland.

In 1617, the Spanish viceroy of Naples tried to break Venice's control of the Adriatic. Rumors of plots and conspiracies circulated in Venice. The Spanish ambassador was suspected. The Council of Ten acted quickly, and the Spanish ambassador was recalled.

Tension with Spain increased in 1622 when Antonio Foscarini, a senator and ambassador, was wrongly accused of spying for Spain and killed. Later, it was discovered he was innocent, and the news spread across Europe.

In 1628, Venice got involved in Italian politics again. When the Duke of Mantua died, a French prince became the new duke. This changed the balance of power in northern Italy, which Spain had controlled. Venice allied with France against the Habsburgs and Savoy. The Venetian army was defeated trying to help Mantua, which was sacked. The peace treaty was made mostly without Venice's input. The war also brought a plague in 1630, killing 50,000 people in Venice, a third of its population. The church of Santa Maria della Salute was built as thanks for the end of the plague.

In 1638, pirates from Algiers and Tunis entered the Adriatic. A Venetian commander attacked them, freeing 3,600 prisoners. The sultan reacted by arresting Venice's ambassador in Constantinople. War was avoided for a short time, but six years later, the Ottomans attacked Candia, the main port on Crete. The Cretan War lasted about 25 years and was the main issue for Venice in the 17th century.

The war also spread to the mainland in 1645 when the Turks attacked Dalmatia. Venice managed to hold its coastal positions there because of its control of the sea. But on August 22, the Cretan stronghold of Khania surrendered.

The biggest Turkish effort was against Sebenico in Croatia, which was besieged in 1647. The siege failed, and Venice regained some forts inland. In Crete, however, the situation was more serious. Venice's strategy was to block the Dardanelles to stop the Turkish fleet from supplying troops on Crete. There were some successes, including two victories in the Dardanelles in 1655 and 1656, but they didn't change the overall situation. In 1657, a three-day sea battle resulted in a crushing defeat for Venice.

When the war between France and Spain ended in 1659, Venice received more help from Christian states. But an expedition to retake Khania failed in 1666. In 1669, another attempt to lift the siege of Candia also failed. The French left, and only 3,600 men were left in Candia. Captain Francesco Morosini negotiated its surrender on September 6, 1669. The island of Crete was given to the Ottomans, except for a few small Venetian bases. Venice kept the islands of Tinos and Cerigo and its conquests in Dalmatia.

In 1684, after the Turks were defeated at the siege of Vienna, Venice joined an alliance, the Holy League, with Austria against the Ottomans. Russia later joined. At the start of the Morean War (1684–99), Francesco Morosini captured the island of Levkas and set out to retake Greek ports. Between June 1685 and August, he secured the Peloponnese for Venice. In September, during an attack on Athens, a Venetian cannon blew up the Parthenon. Venetian lands in Dalmatia also grew. However, an attempt to regain Negropont in 1688 failed. Morosini's successors didn't achieve lasting results, despite some victories. The Treaty of Karlowitz (1699) favored Austria and Russia more than Venice. Venice failed to regain its old bases in the Mediterranean, even with its new conquests.

A new conflict was brewing over the Spanish Succession. Both France and the Habsburg empire tried to get Venice as an ally. But the Venetian government chose to remain neutral. Venice stayed true to this policy of neutrality until the end, facing an unavoidable decline but living in luxury famous throughout Europe.

The Decline of Venice

In December 1714, the Turks declared war on Venice. At this time, Venice's main overseas territory, the "Kingdom of the Morea" (Peloponnese), was poorly supplied and vulnerable.

The Turks took the islands of Tinos and Aegina, crossed the isthmus, and took Corinth. The Venetian fleet commander decided to save the fleet rather than risk it for the Morea. By the time he arrived, many cities had fallen. Some Venetian bases on the Ionian islands and Crete were abandoned. The Turks finally landed on Corfù, but its defenders pushed them back. Meanwhile, the Turks suffered a major defeat by the Austrians at Petrovaradin in 1716. New Venetian naval efforts in the Aegean and Dardanelles in 1717 and 1718 had little success. With the Treaty of Passarowitz (1718), Austria gained a lot of land, but Venice lost the Morea. Its small gains in Albania and Dalmatia were little comfort. This was Venice's last war with Turkey.

Venice's decline in the 18th century was also due to new rival ports. Livorno, a new port on the Tyrrhenian Sea, became a key stop for British trade in the Mediterranean. Even more damaging were the Papal town of Ancona and Habsburg Trieste, which became a free port in 1719. These ports took away much of Venice's trade. A Venetian politician said, "Ancona robs us of the trade from both the Levant and the West... Trieste takes nearly all the rest of the trade which comes from Germany."

Even cities on the eastern mainland started getting supplies from Genoa and Livorno. Pirates from North Africa made the situation worse.

In 1779, Carlo Contarini spoke in the Great Council, saying, "All is in disorder, everything is out of control." He called for reforms to change the power held by a small number of rich noble families. The Doge, Paolo Renier, opposed the plan. The Inquisitors (officials who investigated serious crimes) took action, confining some reformers.

On May 29, 1784, Andrea Tron, an influential politician, said that trade "is falling into final collapse." He noted that old laws that made Venice great had been forgotten. He said foreigners were taking over Venice's trade, and capital was being used for "extravagance, idle spectacles, pretentious amusements and vice," instead of supporting industry and trade.

Venice's last naval operation happened in 1784–86. Pirates from Tunis resumed their attacks. When diplomacy failed, Venice took military action. A fleet under Angelo Emo blockaded Tunis and bombarded several cities. These military successes didn't lead to political gains. After Emo's death, peace was made with Tunis by increasing payments to the bey. By 1792, Venice's once great merchant fleet had shrunk to only 309 merchant ships.

In January 1789, Ludovico Manin was elected doge. The costs of the election had grown throughout the 18th century and were now at their highest. A nobleman remarked, "I have made a Friulian doge; the Republic is dead."

Historian C. P. Snow suggested that in its last 50 years, Venetians knew "that the current of history had begun to flow against them." To survive, they would need to change their ways, but they were "fond of the pattern" and "never found the will to break it."

The Fall of the Republic

By 1796, the Republic of Venice could no longer defend itself. Although it still had a fleet, only a few ships were ready for sea. The army consisted of only a few brigades, mostly made up of soldiers from Dalmatia. In spring 1796, the French army under Napoleon crossed into neutral Venice while chasing the Austrians. By the end of the year, French troops occupied Venetian territory up to the Adige River.

In secret talks for the Peace of Leoben (April 18, 1797), the Austrians were promised Venetian lands as the price of peace. However, the peace still imagined that Venice would survive, though limited to the city and its lagoon, perhaps with some compensation. Meanwhile, cities like Brescia and Bergamo revolted against Venice, and anti-French movements grew elsewhere. Napoleon threatened Venice with war on April 9. On April 25, he told Venetian delegates, "I want no more Inquisition, no more Senate; I shall be an Attila to the state of Venice."

A Venetian commander fired on a French ship trying to enter from the Lido forts. On May 1, Napoleon declared war. The French were at the edge of the lagoon. Even cities in the Veneto region had been "revolutionized" by the French, who set up new local governments. On May 12, the Great Council approved a motion to hand over power to a new provisional government. On May 16, the provisional government met. The terms of the peace of Leoben became even harsher in the treaty of Campoformio. Venice and all its possessions became Austrian territory. The agreement was signed at Passariano, in the last doge's villa, on October 18, 1797.

See also

- History of the city of Venice

- Domini di Terraferma

- Timeline of the Venetian Republic

- Venetian Renaissance

- Republic of Pisa

- History of Italy

- Italian people

- Historical states of Italy

- History of Byzantine Empire

- Wars in Lombardy

- Ottoman wars in Europe

- Ottoman Navy

- Patriarchate of Aquileia

- Italian Wars

- Maritime Republics

- Marco Polo

- Napoleonic Wars

- The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice

- Treaty of Campoformio

- Veneto

- History of Friuli

- Istria

- Venetian Dalmatia

- Venetian Slovenia

- Venetian Albania

- Venetian Cyprus

- Medieval demography

- Naval history

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |