Gasparo Contarini facts for kids

Gasparo Contarini (born October 16, 1483 – died August 24, 1542) was an important Italian diplomat, a high-ranking cardinal in the Catholic Church, and a Bishop of Belluno. He believed in talking with Protestants during a time of big religious changes called the Reformation. Gasparo was born in Venice. He worked as Venice's ambassador to Emperor Charles V during a war between them. He was also the first person to correctly explain why the Magellan–Elcano journey around the world seemed to lose a day. This was because of Earth's spin. He helped bring peace and understanding between different groups. Even though he was not a priest at first, he became a cardinal. Contarini was a key leader in efforts to improve the Roman Catholic Church. He also helped the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) get official approval from the Pope. He worked hard to bring religious groups back together in Germany.

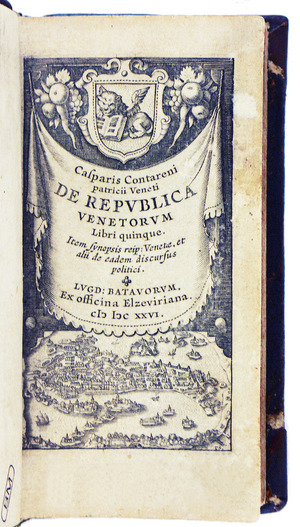

Contarini wrote a book called De magistratibus et republica venetorum. In this book, he praised Venice's government system. He said it was fair, stable, and worked well together. He described how officials were chosen, especially using a lottery system to make sure it was fair for everyone. Contarini also wrote about the Doge, who was Venice's leader. He showed how the Doge was a grand, king-like figure but also represented the city's government, which was run by its citizens. Contarini's writings aimed to show how great Venice's republican system was, while also highlighting its important ceremonies and symbols.

Contents

Gasparo Contarini's Life Story

Gasparo Contarini was born in Venice. He was the oldest son of Alvise Contarini and Polissena Malpiero. His family was part of the old noble House of Contarini. He studied science and philosophy at the University of Padua. After finishing his education, he began working for his home city, Venice.

From 1520 to 1525, he was Venice's ambassador to Emperor Charles V. Venice was at war with Charles V at this time. Contarini's job was to protect Venice's alliance with Francis I of France. He attended a meeting called the Diet of Worms in 1521. However, he never met or spoke with Martin Luther, a key figure in the Protestant Reformation. Contarini traveled with Emperor Charles V in the Netherlands and Spain.

Solving the Time Mystery

Contarini was in Spain when the Magellan–Elcano journey returned in 1522. The sailors brought back valuable spices. They also brought a puzzle: their ship's log showed a date one day earlier than the actual date in Seville. This was even though they had carefully recorded every day of their three-year trip.

Gasparo Contarini was the first European to correctly explain this. He realized that because the ship sailed westward around the world, the sailors experienced one less sunrise than people who stayed in one place. This meant they "lost" a day compared to those who didn't travel around the globe.

Diplomacy and New Roles

In 1526, Contarini represented Venice at the Congress of Ferrara. There, a group called the League of Cognac was formed against the Emperor. This group included France, Venice, and several Italian states. Later, after the Sack of Rome (1527) (when Rome was attacked), Contarini helped bring peace between the Emperor and Pope Clement VII. He also helped the Pope get released. When he returned to Venice, he became a senator and a member of the Great Council.

Becoming a Cardinal

In 1535, Pope Paul III surprised everyone by making Contarini a cardinal. Contarini was a diplomat and not a priest at the time. The Pope wanted to bring this skilled and religious man closer to the Roman Church's goals. Contarini accepted this new role. He became a cardinal on May 21, 1535. By October 1536, he was also made Bishop of Belluno. One of his important writings from his time as a diplomat is his book De magistratibus et republica Venetorum.

As a cardinal, Contarini became a leading figure among the Spirituali. These were people who wanted to reform (improve) the Roman Catholic Church from within. In April 1536, Pope Paul III asked a group to find ways to reform the Church. Contarini was in charge of this group. Pope Paul III liked Contarini's report, called Consilium de Emendanda Ecclesia. However, many of its ideas were not put into action.

Contarini and his friends believed that fixing problems in the Church would solve everything. He wrote letters to the Pope complaining about divisions in the Church. He also spoke out against unfair practices and flattery in the Pope's court. He even criticized what he saw as the Pope's excessive power. Later, in 1539, a future Pope, Paul IV, placed Contarini's report on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, which was a list of books that Catholics were not allowed to read.

In 1541, Cardinal Contarini was the Pope's representative at the Conference of Regensburg. This was a big meeting and religious debate in Germany. It was the last major attempt to bring religious groups back together through discussions. Things were difficult there. The Catholic states were angry, and the Protestants were unwilling to compromise. Contarini's instructions from the Pope seemed flexible but actually had many hidden rules.

However, the Pope's group had sent him hoping he could unite people through shared beliefs. The theologians (religious scholars) and the Emperor wanted peace. So, they created a statement that sounded Protestant in its ideas but Catholic in its words. Contarini approved this statement. Everyone agreed, even Johann Eck, though he later regretted it.

Contarini's own ideas on faith were similar to Protestant views in many ways. However, the Pope's policies changed, and Contarini had to follow his leader. After the conference ended, he advised the Emperor not to restart it. Instead, he suggested that everything should be left to the Pope.

Ignatius Loyola, who founded the Jesuits, said that Cardinal Contarini was very important in getting the Pope's approval for the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) on September 27, 1540. Gasparo Contarini died while he was the Pope's representative in Bologna. This was a time when many of his friends were being forced to leave their homes because of the Inquisition, a Church court.

Venice's Unique Government

Contarini's book De magistratibus et republica venetorum (published in Paris in 1543) is a key source for understanding Venice's special government system in the 1500s and 1600s. This important book was written while he was an ambassador to Emperor Charles V. It praises the different parts of the Venetian government. It makes them sound very harmonious, fair, and peaceful. Historians have shown that Contarini's book describes an ideal version of Venice. He probably wrote it for foreign leaders. This book helped spread the idea that Venice was a stable, unchanging, and successful society. This idea is often called the "myth of Venice."

For example, he described how members of the council were chosen for the senate. He wanted to show how the election system stopped groups from forming. Instead, it made sure that "public benefits are largely extended among the citizens." This meant benefits went to many people, not just "one family." He described a detailed lottery system. This system gave the most chance to choose noble citizens for different jobs. He also noted if two people from the same family were trying for similar positions.

Contarini often mentioned the equality among council members to show how fair the system was. They could "sit down where it pleases them, for there is no place appointed to any." They also "with oath promise to do their utmost diligence, that the laws may be observed." He painted a picture of different individuals working together. The law helped break up any groups that might try to gain too much power. This ensured that important people were chosen fairly and couldn't serve only a small group's interests.

The Doge: A Symbolic Leader

Contarini's description of the Doge clearly shows how this leader was both a grand, king-like figure and a symbol of a government run by many citizens. This careful balance meant that Contarini's Doge, who is the main topic of the second part of his book, was very close to what actually happened. The Doge truly represented the ideal image of Venetian politics. For Contarini, this balance was a key part of Venice's great government.

He called the Doge the "heart," which included "all" of Venice. Contarini placed the Doge at the center of his comparison to a body. This made the Doge a symbol for the city and its people. His job was to make sure that the different parts of the city worked together. This created "the perfection of civil agreement." As a conductor, not a ruler, the Doge represented the whole city. Contarini described his special clothes, privileges, and ceremonies. These descriptions were meant to praise the entire city by describing its important parts.

However, Contarini's main goal was to praise Venice's republican nature. So, he also talked about the "other side" of the Doge's role. He mentioned the Doge's "royal appearing show." Things like the "kingly ornaments," which were "always purple garments or cloth of gold," showed great wealth and power. These were meant to make up for his "limitation of authority." Contarini openly concluded that the Doge was a mix of myth and reality. He said that "in everything you may see the show of a king, but his authority is nothing."

In fact, by the 1500s, almost every public action of the Doge was controlled by laws and ceremonies. He could not buy expensive jewels. He couldn't own property outside Venice. He couldn't display his symbols outside the Ducal Palace. He couldn't decorate his apartment as he wanted. He couldn't receive people in his ducal dress. He couldn't send official letters. He also couldn't have close ties with trade groups. There were many other rules. Legally, power in Venice came from the many councils, not from the Doge, who was mostly a figurehead. The Doge became a clear statement of Venice's republican system. Venice showed off a grand, richly dressed leader, but most of the real power belonged to councils made up of its citizens.

|

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |