Magellan expedition facts for kids

Nao Victoria, the ship accomplishing the circumnavigation and the only to return from the expedition. Detail from a map by Abraham Ortelius.

|

|

| Sponsor | |

|---|---|

| Leader | Ferdinand Magellan (succeeded by Juan Sebastián Elcano) |

| Start | Sanlúcar de Barrameda September 20, 1519 |

| End | Sanlúcar de Barrameda September 6, 1522 |

| Goal | Find a western maritime route to the Spice Islands |

| Ships |

|

| Crew | approx. 270 |

| Survivors | 18 |

| Achievements |

|

| Route | |

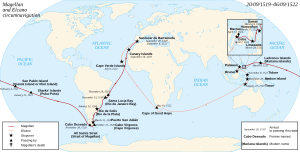

Magellan-Elcano Expedition route displaying the journey's milestones |

|

The Magellan expedition, also known as the Magellan-Elcano expedition, was a famous sea journey. It was paid for by the Spanish King to find a new way to sail west from Europe to the East Indies. This journey ended up being the first time anyone sailed all the way around the Earth in 1522. Many people think it was one of the most important events in history. It changed how people understood the world and led to new ideas in science and trade.

In 1519, Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese explorer, became an admiral for Spain. King Charles I of Spain asked him to lead a fleet of five ships. Their mission was to reach the Spice Islands, also known as the Maluku Islands, which are in present-day Indonesia. Magellan died in the Philippines in 1521 during a battle with local people. After his death, a Spanish sailor named Juan Sebastián Elcano took charge. He successfully led the expedition to the Spice Islands. Elcano then decided to sail back to Spain by going across the Indian Ocean and up the Atlantic Ocean. This completed the first ever circumnavigation of the world in 1522. Because of this, the journey is also called the Magellan–Elcano circumnavigation. King Charles honored Elcano for his achievement. He gave him money every year and a special coat of arms. It showed a globe with the Latin words Primus circumdediste me, which means "You first circumnavigated me."

The main goal of the expedition was to find a western sea route to Asia. This was to create a new way to trade for spices. The eastern route around Africa was controlled by Portugal, due to an agreement called the Treaty of Tordesillas. Magellan left Spain on September 20, 1519. He sailed across the Atlantic Ocean. He discovered the strait that now bears his name. This passage allowed him to sail around the southern tip of South America into the Pacific Ocean. He named this ocean the Pacific because its waters seemed calm. The fleet then made the first crossing of the Pacific Ocean. They stopped in what is now the Philippines, where Magellan was killed. They eventually reached the Moluccas, completing their main goal. A small crew finally returned to Spain on September 6, 1522.

The fleet started with about 270 men and five ships. Four were large sailing ships called carracks, and one was a smaller, faster ship called a caravel. The expedition faced many challenges. These included attempts by Portugal to stop them. There were also mutinies (rebellions by the crew), starvation, and a disease called scurvy. They also faced storms and fights with local people and Portuguese ships. Magellan died in battle in the Philippines. After him, several other leaders took command. Finally, Juan Sebastián Elcano led the journey to the Spice Islands and back to Spain. He and seventeen other men on one ship, the Victoria, were the first to sail around the world. Twelve more crew members, captured by the Portuguese in Cape Verde, arrived in Spain a few weeks later.

King Charles I of Spain mostly paid for the expedition. He hoped it would find a profitable western route to the Moluccas. The eastern route was controlled by Portugal because of the Treaty of Tordesillas. The expedition did find a route, but it was much longer and harder than expected. So, it was not useful for trade. Still, the first circumnavigation was a huge achievement in sailing. It greatly changed how people understood the world.

Contents

Planning the Journey

Christopher Columbus's voyages from 1492 to 1503 aimed to reach the Indies. He wanted to set up direct trade between Spain and Asian kingdoms. The Spanish soon realized that the lands of the Americas were not part of Asia. They were a new continent. The 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas gave Portugal control over the eastern routes around Africa. Vasco da Gama and the Portuguese reached India in 1498 using this route.

Spices were very important for trade. So, Spain urgently needed to find a new trade route to Asia by sailing west. After a meeting in 1505, the Spanish King ordered expeditions to find a western route. Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa reached the Pacific Ocean in 1513. He crossed the Isthmus of Panama. Juan Díaz de Solís died in Río de la Plata in 1516 while exploring South America for Spain.

Ferdinand Magellan was a Portuguese sailor with military experience. He had served in India, Malacca, and Morocco. His friend, Francisco Serrão, was part of the first expedition to the Moluccas in 1511. Serrão reached the Moluccas and settled on the island of Ternate. He sent letters to Magellan from Ternate. These letters described the beauty and richness of the Spice Islands. These letters likely made Magellan want to plan his own expedition there. He later showed these letters to Spanish officials to get their support.

Historians believe that Magellan asked King Manuel I of Portugal many times to fund an expedition to the Moluccas. However, the king always said no. He also refused Magellan's requests for a small pay raise. In late 1515 or early 1516, King Manuel allowed Magellan to serve another ruler. Around this time, Magellan met Rui Faleiro, another Portuguese who was unhappy with King Manuel. The two men worked together to plan a trip to the Moluccas. They decided to offer their plan to the king of Spain. Magellan moved to Seville, Spain, in 1517. Faleiro followed him two months later.

In Seville, Magellan met Juan de Aranda, an agent of the Casa de Contratación. This was Spain's trading house. With Faleiro's help and Aranda's support, they presented their plan to King Charles I. Magellan's project, if successful, would achieve Columbus's dream. It would create a spice route by sailing west without upsetting Portugal. This idea was popular at the time, especially after Balboa found the Pacific. On March 22, 1518, the king named Magellan and Faleiro as captains. They were to search for the Spice Islands. The king also gave them special rights:

- They would have the only right to use the new route for ten years.

- They would become governors of any new lands or islands they found. They would get 5% of the profits from these lands.

- They would receive one-fifth of the profits from the journey.

- They could collect one thousand ducats (a type of coin) from future trips.

- They would be given one island each, besides the six richest ones. They would receive one-fifteenth of the profits from these islands.

The Spanish King mostly paid for the expedition. He provided ships and supplies for two years of travel. However, King Charles V was deeply in debt. So, he turned to the House of Fugger, a rich banking family. Through Archbishop Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca, who led the Casa de Contratación, the King got help from a merchant named Cristóbal de Haro. Haro provided a quarter of the funds and goods for trading.

Skilled mapmakers Jorge Reinel and Diego Ribero helped create the maps for the journey. Ribero was a Portuguese mapmaker who started working for King Charles in 1518. Several problems came up while preparing for the trip. There was not enough money. The king of Portugal tried to stop them. Magellan and other Portuguese sailors were viewed with suspicion by the Spanish. Faleiro also had a difficult personality. But thanks to Magellan's determination, the expedition was finally ready.

Ships and Supplies

The fleet was called Armada del Maluco, named after the Indonesian name for the Spice Islands. It had 5 ships with supplies for two years. The ships were mostly black because they were covered in tar. The total cost of the expedition was about 8.75 million maravedis. This included the ships, food, and salaries.

Food was a very important part of the supplies. It cost about 1.25 million maravedis, almost as much as the ships themselves. Four-fifths of the food was just two items: wine and hardtack (a type of hard biscuit).

The fleet also carried flour and salted meat. Some of the meat came from live animals. The ships had seven cows and three pigs. They also carried cheese, almonds, mustard, and figs. They had a delicacy called Carne de Membrillo, made from quince. The captains enjoyed this, and it unknowingly helped prevent scurvy, a serious disease.

Ships of the Fleet

The fleet started with five ships. The Trinidad was the main ship, called the flagship. The Santiago was a caravel, a smaller, faster ship. The other four ships were larger carracks (also called "nao" in Spanish or "nau" in Portuguese). The Victoria was the only ship to sail all the way around the world. We don't know exactly what the ships looked like, as there are no drawings of them from that time.

| Name | Captain | Crew | Weight (tons) | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trinidad | Ferdinand Magellan | 62 then 61 after a stop-over in Tenerife | 110 | Left Seville with other four ships August 10, 1519. Broke down in Moluccas, December 1521 |

| San Antonio | Juan de Cartagena | 55 | 120 | Left the fleet in the Strait of Magellan, November 1520, returned to Spain on May 6, 1521 |

| Concepción | Gaspar de Quesada | 44 then 45 after a stop-over in Tenerife | 90 | Scuttled (sunk on purpose) in the Philippines, May 1521 |

| Santiago | João Serrão | 31 then 33 after a stop-over in Tenerife | 75 | Wrecked in a storm at Santa Cruz River, on May 3, 1520 |

| Victoria | Luis Mendoza | 45 then 46 after a stop-over in Tenerife | 85 | Successfully sailed around the world, returning to Spain in September 1522, captained by Juan Sebastián Elcano. Mendoza was killed during a mutiny attempt. |

The Crew

The crew had about 270 men, mostly from Spain. Spanish officials were careful about Magellan. They almost stopped him from sailing, changing his mostly Portuguese crew to mostly Spanish men. In the end, about 40 Portuguese sailors were on the fleet. This included Magellan's brother-in-law Duarte Barbosa, João Serrão, Estêvão Gomes, and Magellan's servant Enrique of Malacca. There were also sailors from other countries. This included 29 Italians, 17 French, and a few Flemish, Greek, Irish, English, Asian, and black sailors. Among the Spanish crew, at least 29 were Basques, some of whom did not speak Spanish well.

Ruy Faleiro was supposed to be a co-captain with Magellan. But he developed mental health problems before they left. So, the king removed him from the expedition. Juan de Cartagena took his place as joint commander. Andrés de San Martín became the fleet's mapmaker and astrologer.

Juan Sebastián Elcano, a Spanish merchant ship captain, joined the voyage. He was seeking the king's forgiveness for past mistakes. Antonio Pigafetta, a scholar and traveler from Venice, asked to join the trip. He accepted a small salary and the title of "supernumerary" (an extra person). He became a close helper to Magellan and kept a detailed journal. The only other sailor to write down what happened during the voyage was Francisco Albo. He kept a formal ship's logbook. Juan de Cartagena, who was possibly the illegitimate son of Archbishop Fonseca, was named Inspector General of the expedition. He was in charge of its money and trading.

Crossing the Atlantic Ocean

On August 10, 1519, the five ships led by Magellan left Seville. They sailed down the Guadalquivir River to Sanlúcar de Barrameda, at the river's mouth. They stayed there for more than five weeks. Finally, they set sail on September 20, 1519, leaving Spain.

On September 26, the fleet stopped at Tenerife in the Canary Islands. They took on supplies there, including vegetables and pitch (a sticky tar-like substance). These were cheaper to buy there than in Spain. During the stop, Magellan received a secret message from his father-in-law, Diogo Barbosa. It warned him that some of the Spanish captains were planning a mutiny. Juan de Cartagena, captain of the San Antonio, was leading the plot. Magellan also learned that the King of Portugal had sent two fleets of caravels to arrest him.

On October 3, the fleet left the Canary Islands. They sailed south along the coast of Africa. There was some disagreement about the direction. Cartagena wanted to sail more to the west. Magellan made an unusual choice. He decided to follow the African coast to avoid the Portuguese caravels chasing him.

Towards the end of October, as the fleet neared the equator, they faced many storms. The winds were so strong that they sometimes had to lower their sails. Pigafetta wrote in his journal about seeing St. Elmo's fire during some of these storms. The crew saw this as a good sign:

During these storms the body of St. Anselme appeared to us several times; amongst others, one night that it was very dark on account of the bad weather, the said saint appeared in the form of a fire lighted at the summit of the mainmast, and remained there near two hours and a half, which comforted us greatly, for we were in tears, only expecting the hour of perishing; and when that holy light was going away from us it gave out so great a brilliancy in the eyes of each, that we were near a quarter-of-an-hour like people blinded, and calling out for mercy. For without any doubt nobody hoped to escape from that storm.

After two weeks of storms, the fleet spent some time stuck in calm, equatorial waters. Then, the South Equatorial Current carried them west towards the trade winds.

Journey Through South America

Arriving in Brazil

On November 29, the fleet reached the area of Cape Saint Augustine. The coast of Brazil had been known to the Spanish and Portuguese since about 1500. In the years before Magellan's trip, European countries, especially Portugal, had sent ships to Brazil. They went to collect valuable brazilwood. The fleet had a map of the Brazilian coastline. It was called the Livro da Marinharia (the "Book of the Sea"). Also, one crew member, João Lopes Carvalho, had visited Rio de Janeiro before. Carvalho was asked to guide the fleet down the Brazilian coast to Rio. He sailed aboard the Trinidad. He also helped talk to the local people because he knew some of their Guarani language.

On December 13, the fleet reached Rio de Janeiro. Although it was Portuguese land, they had no permanent settlement there at the time. Magellan saw no Portuguese ships in the harbor, so he knew it was safe to stop.

On December 27, the fleet left Rio de Janeiro. Pigafetta wrote that the native people were sad to see them go. Some followed them in canoes, trying to get them to stay.

Río de la Plata

The fleet sailed south along the South American coast. They hoped to find el paso, a famous strait that would let them pass South America to the Spice Islands. On January 11, they saw a headland (a piece of land sticking out into the sea) with three hills. The crew thought it was "Cape Santa Maria." Around the headland, they found a wide body of water. It stretched as far as they could see to the west-southwest. Magellan believed he had found el paso. But he had actually reached the Río de la Plata, a large river estuary. Magellan sent the Santiago, led by Juan Serrano, to explore the 'strait'. He led the other ships south, hoping to find Terra Australis. This was a southern continent that many people believed existed south of South America. They did not find the southern continent. When they met the Santiago a few days later, Serrano reported that the hoped-for strait was actually the mouth of a river. Magellan did not believe him. He led the fleet through the western waters again, taking frequent soundings (measuring the depth of the water). Serrano's claim was confirmed when the men eventually found themselves in fresh water.

Searching for the Strait

On February 3, the fleet continued south along the South American coast. Magellan believed they would find a strait (or the end of the continent) soon. But the fleet sailed south for another eight weeks without finding a passage. Then, they stopped to spend the winter at St. Julian.

Magellan did not want to miss the strait. So, the fleet sailed as close to the coast as possible. This made it more dangerous to run aground on shoals (shallow areas). The ships only sailed during the day. Lookouts carefully watched the coast for signs of a passage. Besides the dangers of shallow waters, the fleet faced squalls (sudden, strong winds), storms, and colder temperatures as they sailed south into winter.

Spending the Winter

By the third week of March, the weather was so bad that Magellan decided they needed to find a safe harbor. They would wait out the winter there and continue searching for the passage in spring. On March 31, 1520, they spotted a break in the coast. There, the fleet found a natural harbor. They named it Port St. Julian.

The men stayed at St. Julian for five months. Then, they continued their search for the strait.

Easter Mutiny

Within a day of landing at St. Julian, another mutiny attempt happened. Like the one during the Atlantic crossing, it was led by Juan de Cartagena. He was the former captain of the San Antonio. He was helped by Gaspar de Quesada and Luiz Mendoza, captains of the Concepción and Victoria. Again, the Spanish captains questioned Magellan's leadership. They accused him of putting the crew and ships in danger without thinking.

Around midnight on Easter Sunday, April 1, Cartagena and Quesada secretly led thirty armed men onto the San Antonio. Their faces were covered with charcoal. They surprised Álvaro de Mezquita, the ship's new captain. Mezquita was Magellan's cousin and loyal to him. Juan de Elorriaga, the ship's boatswain, fought the mutineers and tried to warn the other ships. Because of this, Quesada stabbed him. He died from his wounds months later.

With the San Antonio taken over, the mutineers controlled three of the fleet's five ships. Only the Santiago (led by Juan Serrano) and the main ship, the Trinidad (led by Magellan), remained loyal. The mutineers pointed the San Antonio's cannon at the Trinidad. But they did not do anything else during the night.

The next morning, April 2, the mutineers tried to gather their forces on the San Antonio and the Victoria. A small boat of sailors drifted off course near the Trinidad. The men were brought aboard. They were persuaded to tell Magellan the details of the mutineers' plans.

Magellan then launched a counterattack against the mutineers on the Victoria. He had some marines from the Trinidad swap clothes with the stray sailors. They approached the Victoria in their small boat. His officer, Gonzalo de Espinosa, also approached the Victoria in a skiff (a small boat). He announced that he had a message for the captain, Luis Mendoza. Espinosa was allowed aboard and into the captain's room. He claimed he had a secret letter. There, Espinosa stabbed Mendoza, killing him instantly. At the same time, the disguised marines came aboard the Victoria to help Espinosa.

With the Victoria lost and Mendoza dead, the remaining mutineers realized they were outsmarted. Cartagena gave up and begged Magellan for mercy. Quesada tried to escape but was stopped. Sailors loyal to Magellan had cut the San Antonio's ropes, causing it to drift towards the Trinidad. Cartagena was captured.

Mutiny Trial

Magellan's cousin, Álvaro de Mezquita, led the trial of the mutineers. It lasted five days. On April 7, Quesada was executed by his foster-brother and secretary, Luis Molina. Molina acted as the executioner in exchange for being forgiven. San Martín, who was suspected of being involved in the plot, was tortured. But afterwards, he was allowed to continue his work as a mapmaker. Cartagena, along with a priest named Pedro Sanchez de Reina, were sentenced to be marooned (left alone on a deserted island). On August 11, two weeks before the fleet left St. Julian, the two men were taken to a small nearby island and left to die. More than forty other plotters, including Juan Sebastián Elcano, were kept in chains for much of the winter. They were made to do hard work like careening the ships. This meant repairing their structure and cleaning the bilge (the lowest part of the ship's hull).

Loss of the Santiago

In late April, Magellan sent the Santiago, captained by Juan Serrano, from St. Julian. Its mission was to scout south for a strait. On May 3, they reached the mouth of a river. Serrano named it Santa Cruz River. The river mouth offered shelter and had good natural resources like fish, penguins, and wood.

After a week exploring Santa Cruz, Serrano set out to return to St. Julian. But a sudden storm caught him while leaving the harbor. The Santiago was thrown around by strong winds and currents. Then it ran aground on a sandbar. All or almost all of the crew were able to get ashore before the ship capsized (turned over). Two men volunteered to walk to St. Julian to get help. After 11 days of hard walking, the men arrived at St. Julian, tired and very thin. Magellan sent a rescue party of 24 men over land to Santa Cruz.

The other 35 survivors from the Santiago stayed at Santa Cruz for two weeks. They could not get any supplies from the wrecked Santiago. But they managed to build huts and fires. They lived on shellfish and local plants. The rescue party found them all alive but tired. They returned to St. Julian safely.

Moving to Santa Cruz

After hearing about the good conditions Serrano found at Santa Cruz, Magellan decided to move the fleet there. They would stay for the rest of the southern winter. After almost four months at St. Julian, the fleet left for Santa Cruz around August 24. They would spend six weeks at Santa Cruz before continuing their search for the strait.

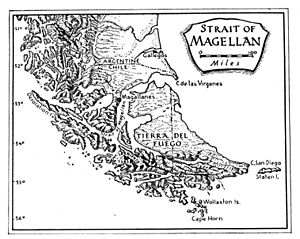

Strait of Magellan

On October 18, the fleet left Santa Cruz heading south. They continued their search for a passage. Soon after, on October 21, they saw a headland at 52°S latitude. They named it Cape Virgenes. Past the cape, they found a large bay. While they were exploring the bay, a storm began. The Trinidad and Victoria made it out to the open sea. But the Concepción and San Antonio were pushed deeper into the bay, towards a point of land. Three days later, the fleet was reunited. The Concepción and San Antonio reported that the storm had pushed them through a narrow passage. It was not visible from the sea and continued for some distance. Hoping they had finally found the strait they were looking for, the fleet followed the path taken by the Concepción and San Antonio. Unlike at Río de la Plata earlier, the water did not lose its saltiness as they went. Also, measurements showed that the waters were consistently deep. This was the passage they sought, which would become known as the Strait of Magellan. At the time, Magellan called it the Estrecho (Canal) de Todos los Santos ("All Saints' Channel"). This was because the fleet traveled through it on November 1, or All Saints' Day.

On October 28, the fleet reached an island in the strait. It was likely Elizabeth Island or Dawson Island. They could pass it in one of two directions. Magellan told the fleet to split up to explore the different paths. They were supposed to meet again within a few days. But the San Antonio never rejoined the fleet. While the rest of the fleet waited for the San Antonio to return, Gonzalo de Espinosa led a small ship to explore the far reaches of the strait. After three days of sailing, they reached the end of the strait and the entrance to the Pacific Ocean. After another three days, Espinosa returned. Pigafetta wrote that when Magellan heard the news of Espinosa's discovery, he cried tears of joy. The fleet's remaining three ships finished the journey to the Pacific by November 28. This was after weeks of searching for the San Antonio without success. Magellan named the waters the Mar Pacifico (Pacific Ocean) because it seemed so calm.

The San Antonio Leaves

The San Antonio did not rejoin the rest of Magellan's fleet in the strait. At some point, they turned around and sailed back to Spain. The ship's officers later said they had arrived early at the meeting place. But it is not clear if this is true. The pilot of the San Antonio at the time, Álvaro de Mezquita, was Magellan's cousin and loyal to him. He tried to rejoin the fleet, firing cannons and setting off smoke signals. At some point, he was taken over in another mutiny attempt, which was successful. He was stabbed by the pilot of the San Antonio, Estêvão Gomes. Mezquita was then put in chains for the rest of the journey. Gomes was known to dislike Magellan. Pigafetta wrote that "Gomes... hated the Captain General exceedingly." This was because Gomes had hoped to have his own expedition to the Moluccas funded instead of Magellan's. Shortly before the fleet separated, Gomes had argued with Magellan about what to do next. Magellan and the other officers agreed to continue west to the Moluccas. They thought their 2–3 months of food would be enough. But Gomes argued that they should return to Spain the way they came. He wanted to gather more supplies for another trip through the strait.

The San Antonio reached Seville about six months later, on May 6, 1521. A trial of the ship's men followed, lasting six months. Mezquita was the only one loyal to Magellan. So, most of the statements painted a bad and twisted picture of Magellan's actions. In particular, to justify the mutiny at St. Julian, the men claimed that Magellan had tortured Spanish sailors. (During the return trip across the Atlantic, Mezquita was tortured into signing a statement saying this.) They also claimed they were just trying to make Magellan follow the king's orders. In the end, none of the mutineers faced charges in Spain. Magellan's reputation suffered, as did his friends and family. Mezquita was kept in jail for a year after the trial. Magellan's wife, Beatriz, had her money cut off. She was placed under house arrest, along with their son.

Crossing the Pacific Ocean

Magellan and other mapmakers at the time did not know how huge the Pacific Ocean was. He thought that South America was separated from the Spice Islands by a small sea. He expected to cross it in just three or four days. But they spent three months and twenty days at sea. Then they finally reached Guam and later the Philippines.

The fleet entered the Pacific from the Strait of Magellan on November 28, 1520. They first sailed north, following the coast of Chile. By mid-December, they changed their course to west-north-west. They were unlucky. If their path had been slightly different, they could have found many Pacific islands. These islands would have offered fresh food and water. Examples include the Juan Fernández Islands, the Marshall Islands, Easter Island, the Society Islands, or the Marquesas Islands. As it was, they only found two small uninhabited islands during the crossing. They could not land on them. This is why they named them islas Infortunadas (Unfortunate Islands). The first, seen on January 24, they named San Pablo (likely Puka-Puka). The second, seen on February 21, was likely Caroline Island. They crossed the equator on February 13.

They did not expect such a long journey. So, the ships did not have enough food and water. Much of the seal meat they had stored rotted in the hot equatorial weather. Pigafetta described the terrible conditions in his journal:

we only ate old biscuit reduced to powder, and full of grubs, and stinking from the dirt which the rats had made on it when eating the good biscuit, and we drank water that was yellow and stinking. We also ate the ox hides which were under the main-yard, so that the yard should not break the rigging: they were very hard on account of the sun, rain, and wind, and we left them for four or five days in the sea, and then we put them a little on the embers, and so ate them; also the sawdust of wood, and rats which cost half-a-crown each, moreover enough of them were not to be got.

Also, most of the men suffered from scurvy. People at that time did not know what caused it. Pigafetta reported that out of the 166 men who started the Pacific crossing, 19 died. He also said "twenty-five or thirty fell ill of diverse sicknesses." Magellan, Pigafetta, and other officers did not get scurvy. This might be because they ate preserved quince. They did not know it, but quince contains vitamin C, which prevents scurvy.

Guam and the Philippines

On March 6, 1521, the fleet reached the Mariana Islands. The first land they saw was likely the island of Rota. But the ships could not land there. Instead, they dropped anchor thirty hours later on Guam. They were met by native Chamorro people in proas. These were a type of outrigger canoe that Europeans had never seen before. Dozens of Chamorros came aboard and started taking things from the ship. This included ropes, knives, and anything made of iron. At some point, there was a fight between the crew and the natives. At least one Chamorro was killed. The remaining natives fled with the goods they had taken. They also took Magellan's bergantina (the small boat kept on the Trinidad) as they left. Because of this act, Magellan called the island Isla de los Ladrones (Island of Thieves).

The next day, Magellan fought back. He sent a group ashore that looted and burned forty or fifty Chamorro houses. They also killed seven men. They got back the bergantina. The fleet left Guam the next day, March 9, and continued sailing west.

The Philippines

The fleet reached the Philippines on March 16. They would stay there until May 1. This expedition was the first time Europeans were known to have contact with the Philippines. Magellan's main goal was to find a passage through South America to the Moluccas and return to Spain with spices. But at this point in the journey, Magellan seemed to become very keen on converting the local tribes to Christianity. In doing so, Magellan eventually got involved in a local political fight. He died in the Philippines, along with many other officers and crew members.

On March 16, a week after leaving Guam, the fleet first saw the island of Samar. Then they landed on the island of Homonhon, which was not inhabited at the time. They met friendly local people from the nearby island of Suluan and traded supplies with them. They spent almost two weeks on Homonhon, resting and getting fresh food and water. They left on March 27. On the morning of March 28, they neared the island of Limasawa. They met some natives in canoes. These canoes then alerted balangay warships of two local rulers from Mindanao. These rulers were on a hunting trip in Limasawa. For the first time on the journey, Magellan's slave Enrique of Malacca found that he could talk to the natives in Malay. This showed that they had indeed sailed around the world and were getting close to familiar lands. They exchanged gifts with the natives. They received porcelain jars with Chinese designs. Later that day, they met the local leaders, Rajah Kolambu and Rajah Siawi. Magellan became a "blood brother" to Kolambu. They performed a local blood compact ritual.

Magellan and his men noticed that the Rajahs had gold ornaments on their bodies. They also served food on gold plates. The Rajahs told them that gold was plentiful in their homelands in Butuan and Calagan (Surigao). The locals were eager to trade gold for iron at the same value. While at Limasawa, Magellan showed some of the natives Spanish armor, weapons, and cannons. They seemed very impressed.

First Mass

On Sunday, March 31, Easter Day, Magellan and fifty of his men went ashore to Limasawa. They took part in the first Catholic Mass in the Philippines. The fleet's chaplain led the Mass. Kolambu, his brother (who was also a local leader), and other islanders joined the ceremony. They showed interest in the Christian religion. After Mass, Magellan's men put a cross on the highest hill on the island. They officially declared the island, and all of the Philippines (which he called the Islands of St Lazarus), as belonging to Spain.

Cebu

On April 2, Magellan held a meeting to decide what the fleet should do next. His officers urged him to head south-west for the Moluccas. But instead, he decided to go further into the Philippines. On April 3, the fleet sailed north-west from Limasawa towards the island of Cebu. Magellan had learned about Cebu from Kolambu. Some of Kolambu's men guided the fleet to Cebu. They saw Cebu on April 6 and landed there the next day. Cebu had regular contact with Chinese and Arab traders. Visitors usually had to pay a tribute (a payment) to trade there. Magellan convinced the island's leader, Rajah Humabon, to drop this requirement.

Just like in Limasawa, Magellan showed off the fleet's weapons to impress the locals. Again, he also taught the natives about Christianity. On April 14, Humabon and his family were baptized. They were given an image of the Holy Child (later known as Santo Niño de Cebu). In the following days, other local leaders were baptized. In total, 2,200 locals from Cebu and nearby islands converted to Christianity.

Magellan learned that a group on the island of Mactan, led by Lapu-Lapu, did not want to convert to Christianity. He ordered his men to burn their homes. When they still refused, Magellan told his council on April 26 that he would take armed men to Mactan. He would make them submit by force.

Battle of Mactan

Magellan gathered 60 armed men from his crew to fight Lapu-Lapu's forces. Some men from Cebu followed Magellan to Mactan. But Magellan told them not to join the fight, only to watch. He first sent a messenger to Lapu-Lapu. He offered him one last chance to accept the king of Spain as their ruler and avoid bloodshed. Lapu-Lapu refused. Magellan took 49 men to the shore, while 11 stayed to guard the boats. Magellan's forces had better armor and weapons. But Lapu-Lapu's forces greatly outnumbered them. Pigafetta, who was there, estimated the enemy's number at 1,500. Magellan's forces were pushed back and clearly defeated. Magellan died in battle, along with several comrades. This included Cristóvão Rebelo, Magellan's illegitimate son.

May 1 Massacre

After Magellan's death, the remaining men held an election. They chose a new leader for the expedition. They picked two co-commanders: Duarte Barbosa, Magellan's brother-in-law, and Juan Serrano. Magellan's will said his slave, Enrique, should be freed. But Barbosa and Serrano demanded that Enrique continue to work as their interpreter and follow their orders. Enrique had some secret talks with Humabon. This led him to betray the Spanish.

On May 1, Humabon invited the men ashore for a big feast. About thirty men attended, mostly officers, including Serrano and Barbosa. Towards the end of the meal, armed Cebuanos entered the hall. They murdered the Europeans. Twenty-seven men were killed. Juan Serrano, one of the newly chosen co-commanders, was left alive. He was brought to the shore facing the Spanish ships. Serrano begged the men on board to pay a ransom to the Cebuanos. But the Spanish ships left the port, and Serrano was (most likely) killed. In his story, Pigafetta thought that João Carvalho, who became the main commander after Barbosa and Serrano were gone, abandoned Serrano (his former friend) so he could stay in charge of the fleet.

Reaching the Moluccas

Only 115 men were left out of the original 277 who had sailed from Seville. So, they decided the fleet did not have enough men to keep operating three ships. On May 2, the Concepción was emptied and set on fire. With Carvalho as the new captain-general, the two remaining ships, the Trinidad and Victoria, spent the next six months sailing through Southeast Asia. They were searching for the Moluccas. Along the way, they stopped at several islands, including Mindanao and Brunei. During this time, they acted like pirates. They robbed a junk (a type of Chinese sailing ship) that was going from the Moluccas to China.

On September 21, Carvalho was made to step down as captain-general. Martin Mendez replaced him. Gonzalo de Espinosa became captain of the Trinidad, and Juan Sebastián Elcano became captain of the Victoria.

The ships finally reached the Moluccas on November 8. They arrived at the island of Tidore. The island's leader, al-Mansur (known as Almanzor to the officers), greeted them. Almanzor was friendly to the men. He quickly declared loyalty to the king of Spain. A trading post was set up in Tidore. The men began buying huge amounts of cloves in exchange for goods like cloth, knives, and glassware.

Around December 15, the ships tried to sail from Tidore, loaded with cloves. But the Trinidad, which was in bad shape, was found to be taking on water. The departure was delayed while the men, helped by the locals, tried to find and fix the leak. When they could not fix it, they decided that the Victoria would leave for Spain by a western route. The Trinidad would stay behind for some time to be repaired. Then it would head back to Spain by an eastern route, which would involve crossing the American continent by land. Several weeks later, the Trinidad left and tried to return to Spain using the Pacific route. This attempt failed. The Trinidad was captured by the Portuguese. It was eventually wrecked in a storm while anchored under Portuguese control.

Return to Spain

The Victoria set sail for home via the Indian Ocean route on December 21, 1521. It was commanded by Juan Sebastián Elcano. By May 6, 1522, the Victoria rounded the Cape of Good Hope. They had only rice left for food. Twenty crewmen died of starvation by July 9, 1522. On that day, Elcano stopped at Portuguese Cape Verde for supplies. The crew was surprised to learn that the date was actually July 10, 1522. They had recorded every day of the three-year journey without missing any. They lost one day because they traveled west while sailing around the world. This was in the same direction as the sun appears to move across the sky. At first, they had no trouble buying things. They pretended they were returning to Spain from the Americas. However, the Portuguese held 13 crew members after finding out that the Victoria was carrying spices from the East Indies. The Victoria managed to escape with its cargo of 26 tons of spices (cloves and cinnamon).

On September 6, 1522, Elcano and the remaining crew of Magellan's voyage arrived in Sanlúcar de Barrameda in Spain aboard the Victoria. This was almost exactly three years after they had left. They then sailed upriver to Seville. From there, they traveled by land to Valladolid, where they met the Emperor.

Survivors

When the Victoria, the only surviving ship and the smallest in the fleet, returned to the starting harbor, only 18 men were on board. The original crew had been about 270 men. Besides the returning Europeans, the Victoria also had three men from the Moluccas who had joined at Tidore.

| Name | Origin | Final rank |

|---|---|---|

| Juan Sebastián Elcano | Getaria | Captain |

| Francisco Albo | Chios | Pilot |

| Miguel de Rodas | Rhodes | Shipmaster |

| Juan de Acurio | Bermeo | Boatswain |

| Martín de Judicibus | Savona | Sailor |

| Hernándo de Bustamante | Merida | Barber |

| Antonio Pigafetta | Vicenza | Man-At-Arms |

| Maestre Anes | Aachen | Gunner |

| Diego Gallego | Bayona | Sailor |

| Antonio Hernández Colmenero | Huelva | Sailor |

| Nícolas de Napolés | Napol de Roma | Sailor |

| Francisco Rodríguez | Sevilla | Sailor |

| Juan Rodríguez de Huelva | Huelva | Sailor |

| Miguel de Rodas | Rhodes | Sailor |

| Juan de Arratía | Bilbao | Shipboy |

| Juan de Santander (Sant Andrés) | Cueto | Shipboy |

| Vasco Gómez Gallego | Bayona | Shipboy |

| Juan de Zubileta | Barakaldo | Page |

A few weeks later, another 13 men (12 Europeans and one Moluccan) returned to Seville. They had been held captive in Cape Verde. They also completed the circumnavigation. They were:

- Martín Méndez, writer

- Pedro de Tolosa, pantry worker

- Richard de Normandía, carpenter

- Roldán de Argote, gunner

- Pedro de Tenerife, gunner

- Juan Martín, extra crew member

- Simón de Burgos, extra crew member

- Felipe de Rodas, skilled sailor

- Gómez Hernández, skilled sailor

- Socacio Alonso, skilled sailor

- Pedro de Chindurza, skilled sailor

- Vasquito Gallego, cabin boy

- "Manuel", a Moluccan with no known role

Between 1525 and 1526, the survivors of the Trinidad were taken to a prison in Portugal. They had been captured by the Portuguese in the Moluccas. They were finally released after seven months of talks. Only five survived:

- Juan Rodríguez

- Gaspar de Espinosa, officer

- Leone Pancaldo, pilot

- Ginés de Mafra, skilled sailor

- Hans Vargue, gunner (who died in Portugal)

The following six men are also considered to have successfully sailed around the world. They died after the Victoria and Trinidad had crossed the fleet's outbound path.

| Name | Origin | Final rank |

|---|---|---|

| Diego Garcia de Trigueros | Huelva | Sailor |

| Pedro de Valpuesta | Burgos | Man-At-Arms |

| Martín de Magallanes | Lisbon | Man-At-Arms |

| Estevan Villon | Trosic, Britanny | Sailor |

| Andrés Blanco | Tenerife | Shipboy |

| Gonzalo Gómez de Espinosa | Burgos | Captain |

Records of the Journey

Antonio Pigafetta's journal, later published as Relazione del primo viaggio intorno al mondo, is the main source for most of what we know about Magellan's expedition. The first printed report about the circumnavigation was a letter written by Maximilianus Transylvanus. He was a relative of the expedition's sponsor, Cristóbal de Haro. Transylvanus interviewed survivors in 1522 and published his story in 1523.

There is also a record from Peter Martyr d'Anghiera. It was written in Spanish in 1522 or 1523, then lost, and published again in 1530.

Another reliable source is the 1601 and 1615 chronicles by Spanish historian Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas. Herrera's account is very accurate because he had access to Spanish and Portuguese sources that are now lost. This includes Andrés de San Martín's navigation notes and papers. San Martin, the fleet's chief pilot and mapmaker, disappeared in the Cebu massacre on May 1, 1521.

Besides Pigafetta's journal, 11 other crew members kept written accounts of the voyage:

- Francisco Albo: the Victoria's pilot logbook, first mentioned in 1788, and fully published in 1837. He also gave a statement on October 18, 1522.

- Martín de Ayamonte: a short account first published in 1933.

- Giovanni Battista: two letters from December 21, 1521, and October 25, 1525.

- Hernando de Bustamante: a statement on October 18, 1522.

- Juan Sebastián Elcano: a letter written on September 6, 1522, and a statement on October 18, 1522.

- Gonzalo Gómez de Espinosa: a letter written on January 12, 1525, a statement on August 2, 1527, and a statement from September 2 to 5, 1527.

- Ginés de Mafra: a detailed account first published in 1920, a statement on August 2, 1527, and a statement from September 2 to 5, 1527.

- Martín Méndez: the Victoria's logbook.

- Leone Pancaldo: a long logbook (first published in 1826), a letter written on October 25, 1525, a statement on August 2, 1527, and a statement from September 2 to 5, 1527.

- An anonymous Portuguese crew member: a long manuscript, first published in 1937, known as "the Leiden manuscript." It was possibly written by Gonzalo Gómez de Espinosa and likely a Trinidad crew member.

- Another anonymous Portuguese crew member: a very short account, first published in 1554, written by a Trinidad crew member.

Impact of the Journey

Later Expeditions

There was no clear eastern boundary for the world at that time. So, in 1524, both Spain and Portugal tried to find the exact location of the antimeridian of Tordesillas. This imaginary line would divide the world into two equal halves. They wanted to solve the "Moluccas issue." A group met several times but could not agree. The knowledge at that time was not enough to calculate longitude accurately. Each country claimed the islands for their ruler.

In 1525, soon after Magellan's expedition returned, Charles V sent another expedition. It was led by García Jofre de Loaísa. Its goal was to take control of the Moluccas. Spain claimed these islands were in their zone according to the Treaty of Tordesillas. This expedition included famous Spanish sailors, like Juan Sebastián Elcano. He and many others died during the voyage. The young Andrés de Urdaneta was also on this trip. They had trouble reaching the Moluccas and landed at Tidore. The Portuguese were already settled in nearby Ternate. The two nations fought for almost ten years over who owned the islands. The islands were still home to native people. An agreement was finally reached with the Treaty of Zaragoza, signed in 1529 between Spain and Portugal. It gave the Moluccas to Portugal and the Philippines to Spain.

In 1565, Andrés de Urdaneta discovered the Manila-Acapulco route. This was a new trade route across the Pacific.

The path Magellan mapped was later used by other sailors. For example, Sir Francis Drake followed it during his own trip around the world in 1578.

Scientific Discoveries

Magellan's expedition was the first to sail around the globe. It was also the first to navigate the strait in South America that connects the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Other Europeans adopted Magellan's name for the Pacific Ocean.

Magellan's crew saw several animals that were completely new to European science. This included a "camel without humps," which was probably a guanaco. These animals live in Tierra del Fuego. The llama, vicuña, and alpaca naturally live in the Andes mountains. They also saw a black "goose" that had to be skinned instead of plucked. This was a penguin.

The full size of the Earth was understood after their voyage. Their journey was 14,460 Spanish leagues (about 60,440 km or 37,560 miles). The global expedition showed the need for an International Date Line. When they arrived at Cape Verde, the crew was surprised to learn that their ship's date of July 9, 1522, was one day behind the local date of July 10, 1522. They had recorded every day of the three-year journey without missing any. They lost one day because they traveled west during their trip around the globe. This was in the same direction as the sun appears to move across the sky. Although the Kurdish mapmaker Abu'l-Fida (1273–1331) had predicted this one-day difference, Cardinal Gasparo Contarini was the first European to correctly explain why it happened.

500th Anniversary

In 2017, Portugal asked UNESCO to honor the circumnavigation route. The idea was to make it a World Heritage Site called "Route of Magellan." In 2019, Portugal and Spain made a joint application for this.

In 2019, many events took place to mark the 500th anniversary of the voyage. These included exhibitions in various Spanish cities.

To celebrate the 500th anniversary of Magellan's arrival in the Philippines in 2021, the National Quincentennial Committee will put up special markers. These markers will be placed at the points where the fleet anchored.

| Marker | Site in the Philippines |

|---|---|

| Landing | Homonhon, Limasawa, Mactan, Cebu, Quipit, Tagusao, Buliluyan, Mapun and Sarangani |

| Anchorage | Guiuan, Suluan, Gigatigan, Bohol, Balabac, Kawit and Balut |

| Landmark | Hibuson, Hinunangan, Baybay, Pilar, Poro, Pozon, Panilongo, Palawan, Sulu, Basilan, Manalipa, Tukuran, Cotabato, Kamanga and Batulaki |

Images for kids

-

Cover page of the Roman edition of Maximilianus Transylvanus's De Moluccis Insulis.... This was the first printed story of the Magellan expedition, published in 1523.

See also

In Spanish: Expedición de Magallanes-Elcano para niños

In Spanish: Expedición de Magallanes-Elcano para niños