Treaty of Zaragoza facts for kids

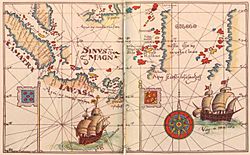

The 1494 Tordesillas Treaty meridian (purple) and the Moluccas antimeridian (green), set by the Treaty of Zaragoza, 1529

|

|

| Signed | 22 April 1529 |

|---|---|

| Location | Zaragoza, Aragon |

| Parties | |

The Treaty of Zaragoza (also called the Capitulation of Zaragoza) was a peace treaty signed on April 22, 1529. It was an agreement between Castile (which was part of Spain) and Portugal.

The treaty was signed by King John III of Portugal and Emperor Charles V of the Habsburg family. It took place in the city of Zaragoza, which was in the Kingdom of Aragon (also part of Spain).

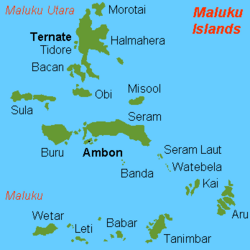

The main goal of the treaty was to decide which areas in Asia belonged to Spain and which belonged to Portugal. This was to solve a big problem called the "Moluccas issue." Both kingdoms wanted to control the very valuable Spice Islands (now called the Malukus in Indonesia). They both believed these islands were in their part of the world, according to an earlier agreement from 1494 called the Treaty of Tordesillas.

The problem started around 1520. Expeditions from both Spain and Portugal reached the Pacific Ocean. But they didn't have a clear line drawn on the other side of the world to show where each country's area ended.

Why the Treaty Was Needed

Long before this treaty, the pope had issued special orders (called bulls) to help Portugal and Spain divide up newly discovered lands. In 1494, Portugal and Spain signed the Treaty of Tordesillas. This treaty drew an imaginary line in the Atlantic Ocean. Lands to the west of this line were for Spain, and lands to the east were for Portugal.

However, the exact location of this line was never perfectly clear. Each country tried to interpret it in a way that helped them the most.

In 1498, a Portuguese explorer named Vasco da Gama found a sea route to India. Soon, Portuguese ships took control of major ports there. In 1511, Afonso de Albuquerque conquered Malacca, which was a very important trading center in Southeast Asia.

The Portuguese then learned about the secret location of the "spice islands." These were the Bandas, Ternate, and Tidore in the Malukus. These islands were the only source of valuable spices like nutmeg and cloves. This made them very important for European trade.

Albuquerque sent an expedition to these islands in 1512. One of his officers, Francisco Serrão, ended up in Ternate. He got permission to build a Portuguese trading post and a fort there.

Serrão wrote letters about the Spice Islands to his friend, Ferdinand Magellan. These letters helped Magellan convince the Spanish king to pay for the first trip around the world. On November 6, 1521, Magellan's fleet (then led by Juan Sebastián Elcano) reached the Moluccas from the east. Sadly, Serrão died in Ternate around the same time Magellan was killed in the Battle of Mactan in the Philippines.

After Magellan's journey (1519–1522), Spain's King Charles V sent another expedition. This one was led by García Jofre de Loaísa. Their goal was to set up a colony in the Moluccas. Spain believed these islands were in their zone according to the Treaty of Tordesillas. The expedition reached the Malukus and built a fort in Tidore. This led to fighting with the Portuguese, who were already in Ternate. The fighting continued for almost ten years.

Trying to Solve the Problem

In 1524, both Spain and Portugal tried to solve the dispute. They organized a meeting called the "Junta de Badajoz–Elvas." Each country sent three astronomers, mapmakers, sailors, and mathematicians. They formed a committee to find the exact location of the "antimeridian" of Tordesillas. An antimeridian is the line on the opposite side of the world from another line. The idea was to divide the whole world into two equal halves.

The Portuguese group included important people like António de Azevedo Coutinho and Lopo Homem, a mapmaker. The Spanish group included Diogo Ribeiro, who used to be a Portuguese mapmaker.

A funny story is told about this meeting. A young boy supposedly stopped the Portuguese group and asked if they were going to divide the world. When they said yes, the boy made a rude gesture and told them to draw their line through his backside!

The committee met many times in Badajoz (Spain) and Elvas (Portugal). But they couldn't agree. People at that time didn't know enough about longitude (east-west position) to draw an accurate line. Each group used maps that showed the islands in their own half of the world.

So, King John III of Portugal and Emperor Charles V of Spain agreed not to send more people to the Moluccas until the issue was settled.

Between 1525 and 1528, Portugal sent more expeditions to the area around the Maluku Islands. Explorers like Gomes de Sequeira and Diogo da Rocha reached the Caroline Islands. Other explorers like Martim Afonso de Melo also saw the Aru Islands and the Tanimbar Islands. In 1526, Jorge de Meneses reached Papua New Guinea.

Spain also sent more expeditions. The Loaísa expedition went to the Moluccas from 1525 to 1526. Then, Hernán Cortés (who was in Mexico) prepared another expedition led by Álvaro de Saavedra Cerón in 1528. This was to compete with the Portuguese. Some Spanish explorers were captured by the Portuguese and sent back to Europe. Álvaro de Saavedra Cerón explored parts of New Guinea and other islands.

The two royal families also became closer. In 1525, Charles V's younger sister, Catherine, married John III of Portugal. In 1526, Charles V married King John's sister, Isabella of Portugal. These marriages made the two countries more friendly. Emperor Charles V wanted to avoid conflict so he could focus on problems in Europe. Also, the Spanish didn't yet know how to bring spices from the Moluccas back to Europe using the eastern route across the Pacific. That route was only found in 1565.

The Treaty's Agreement

The Treaty of Zaragoza set the eastern border between the two countries' areas. This line was about 297.5 leagues (about 1,763 kilometers or 952 nautical miles) east of the Maluku Islands. This meant the Spice Islands were clearly in Portugal's area.

In return, the King of Portugal paid Emperor Charles V 350,000 gold ducats. A ducat was a type of gold coin.

The treaty had a special rule: if the emperor ever wanted to cancel the deal, he could. If he did, Portugal would get their money back, and each country would go back to how things were before. However, this never happened. The emperor really needed Portugal's money to pay for a war in Europe called the War of the League of Cognac against Francis I of France.

The treaty didn't change the original line from the Treaty of Tordesillas. It also didn't say that the world was divided into two equal 180-degree halves. Instead, Portugal's share of the world was about 191 degrees, and Spain's was about 169 degrees. There was still some uncertainty about the exact size of these parts.

Under the treaty, Portugal got control of all lands and seas west of the new line. This included all of Asia and its nearby islands that had been "discovered." Spain was left with most of the Pacific Ocean.

The Philippines were not directly mentioned in the treaty. But because they were far west of the line, Spain gave up any claim to them. However, by 1542, King Charles V decided to try and colonize the Philippines anyway. He thought Portugal wouldn't complain too much because the islands didn't have spices. He failed, but his son, King Philip II, succeeded in 1565. He set up the first Spanish trading post in Manila. Just as his father expected, Portugal didn't strongly oppose it.

Later, Portugal's colonization in Brazil expanded far west of the Tordesillas line. This went into what would have been Spanish land. New borders for Brazil were later set in the Treaty of Madrid (13 January 1750).

See also

In Spanish: Tratado de Zaragoza para niños

In Spanish: Tratado de Zaragoza para niños

- 141st meridian east

- Indonesia–Papua New Guinea relations

- South Australia–Victoria border dispute